Robert Frost

Robert Frost | |

|---|---|

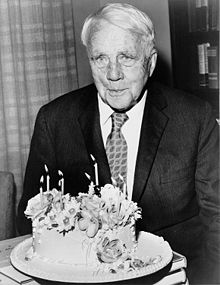

Frost in 1949 | |

| Born | March 26, 1874 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Died | January 29, 1963 (aged 88) Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, playwright |

| Notable works | A Boy's Will, North of Boston, New Hampshire[1] |

| Notable awards | |

| Spouse |

Elinor Miriam White

(m. 1895; died 1938) |

| Children | 6 |

| Signature | |

Robert Lee Frost (March 26, 1874 – January 29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American colloquial speech,[2] Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New England in the early 20th century, using them to examine complex social and philosophical themes.[3]

Frequently honored during his lifetime, Frost is the only poet to receive four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America's rare "public literary figures, almost an artistic institution".[4] Frost was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 and in 1961 was named poet laureate of Vermont. Randall Jarrell wrote: "Robert Frost, along with Stevens and Eliot, seems to me the greatest of the American poets of this century. Frost's virtues are extraordinary. No other living poet has written so well about the actions of ordinary men; his wonderful dramatic monologues or dramatic scenes come out of a knowledge of people that few poets have had, and they are written in a verse that uses, sometimes with absolute mastery, the rhythms of actual speech".[5] In his 1939 essay "The Figure a Poem Makes", Frost explains his poetics:

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader. No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader. For me the initial delight is in the surprise of remembering something I didn't know I knew...[Poetry] must be a revelation, or a series of revelations, for the poet as for the reader. For it to be that there must have been the greatest freedom of the material to move about in it and to establish relations in it regardless of time and space, previous relation, and everything but affinity.[6]

Biography

Early life

Robert Frost was born in San Francisco to journalist William Prescott Frost Jr. and Isabelle Moodie.[2] His father was a descendant of Nicholas Frost of Tiverton, Devon, England, who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634 on the Wolfrana, and his mother was a Scottish immigrant.

Frost was also a descendant of Samuel Appleton, one of the early English settlers of Ipswich, Massachusetts, and Rev. George Phillips, one of the early English settlers of Watertown, Massachusetts.[7]

Frost's father was a teacher and later an editor of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin (which later merged with the San Francisco Examiner), and an unsuccessful candidate for city tax collector.[8] After his death on May 5, 1885, the family moved across the country to Lawrence, Massachusetts, under the patronage of Robert's grandfather William Frost Sr., who was an overseer at a New England mill. Frost graduated from Lawrence High School in 1892, where he published his first poem in the high school magazine, served as class poet and, with his future wife Elinor White, was co-valedictorian.[9][3] Frost's mother joined the Swedenborgian church and had him baptized in it, but he left it as an adult.

Although known for his later association with rural life, Frost grew up in the city. He attended Dartmouth College for two months, long enough to be accepted into the Theta Delta Chi fraternity. Frost returned home to teach and to work at various jobs, helping his mother teach her class of unruly boys, delivering newspapers and working in a factory maintaining carbon arc lamps. He said that he did not enjoy these jobs, feeling that his true calling was to write poetry.

Adult years

In 1894, he sold his first poem, "My Butterfly. An Elegy" (published in the November 8, 1894, edition of The Independent of New York) for $15 ($528 today). Proud of his accomplishment, he proposed marriage to Elinor Miriam White, but she demurred, wanting to finish college at St. Lawrence University before they married. Frost then went on an excursion to the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and asked Elinor again upon his return. Having graduated, she agreed, and they were married in Lawrence, Massachusetts, on December 19, 1895.

Frost attended Harvard University from 1897 to 1899, but he left voluntarily due to illness.[10][11][12] Shortly before his death, Frost's grandfather purchased a farm for Robert and Elinor in Derry, New Hampshire; Frost worked the farm for nine years while writing early in the mornings and producing many of the poems that would later become famous. Ultimately his farming proved unsuccessful and he returned to the field of education as an English teacher at New Hampshire's Pinkerton Academy from 1906 to 1911, then at the New Hampshire Normal School (now Plymouth State University) in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

In 1912, Frost sailed with his family to Great Britain, settling first in Beaconsfield, a small town in Buckinghamshire outside London. His first book of poetry, A Boy's Will, was published the next year. In England he made some important acquaintances, including Edward Thomas (a member of the group known as the Dymock poets and Frost's inspiration for "The Road Not Taken"[13]), T. E. Hulme and Ezra Pound. Although Pound would become the first American to write a favorable review of Frost's work, Frost later resented Pound's attempts to manipulate his American prosody.[14] Frost met or befriended many contemporary poets in England, especially after his first two poetry volumes were published in London in 1913 (A Boy's Will) and 1914 (North of Boston).

In 1915, during World War I, Frost returned to America, where Holt's American edition of A Boy's Will had recently been published, and bought a farm in Franconia, New Hampshire, where he launched a career of writing, teaching and lecturing. This family homestead served as the Frosts' summer home until 1938. It is maintained today as The Frost Place, a museum and poetry conference site. He was made an honorary member of Phi Beta Kappa at Harvard[15] in 1916. During the years 1917–20, 1923–25, and, on a more informal basis, 1926–1938, Frost taught English at Amherst College in Massachusetts, notably encouraging his students to account for the myriad sounds and intonations of the spoken English language in their writing. He called his colloquial approach to language "the sound of sense".[16]

He won the first of four Pulitzer Prizes for New Hampshire: A Poem with Notes and Grace Notes (1923).[17] He would win Pulitzers for Collected Poems (1930),[18] A Further Range (1936)[19] and A Witness Tree (1942).[20]

From 1921 to 1962, Frost spent almost every summer and fall teaching at the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College, at its mountain campus at Ripton, Vermont. He is credited with being a major influence upon the development of the school and its writing programs. The college now owns and maintains his former Ripton farmstead, a National Historic Landmark, near the Bread Loaf campus.[21] In 1921, Frost accepted a fellowship teaching post at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where he resided until 1927, when he returned to teach at Amherst. While teaching at the University of Michigan, he was awarded a lifetime appointment at the university as a Fellow in Letters.[22] The Robert Frost Ann Arbor home was purchased by The Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan and relocated to the museum's Greenfield Village site for public tours. Throughout the 1920s, Frost also lived in his colonial-era house in Shaftsbury, Vermont. In 2002, the house was opened to the public as the Robert Frost Stone House Museum[23] and was given to Bennington College in 2017.[23]

In 1934, Frost began to spend winter months in Florida.[24] In March 1935, he gave a talk at the University of Miami.[24] In 1940, he bought a 5-acre (2.0 ha) plot in South Miami, Florida, naming it Pencil Pines; he spent his winters there for the rest of his life.[24] In her memoir about Frost's time in Florida, Helen Muir writes, "Frost had called his five acres Pencil Pines because he said he had never made a penny from anything that did not involve the use of a pencil."[24] His properties also included a house on Brewster Street in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Frost was 86 when he performed a reading at the inauguration of John F. Kennedy on January 20, 1961. He began by attempting to read his poem "Dedication", which he had composed for the occasion, but due to the brightness of the sunlight he was unable to see the text, so he recited "The Gift Outright" from memory instead.[25] In the summer of 1962, Frost accompanied Interior Secretary Stewart Udall on a visit to the Soviet Union in hopes of meeting Nikita Khrushchev to lobby for peaceful relations between the two Cold War powers.[26][27][28][29]

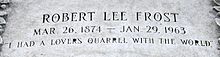

In the early hours of January 29, 1963, Frost died at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston, at the age of 88.[30] He was buried in the Old Bennington Cemetery in Bennington, Vermont. His epitaph, from the last line of his poem "The Lesson for Today" (1942), is: "I had a lover's quarrel with the world."

Personal life

Frost's personal life was plagued by grief and loss. In 1885, when he was 11, his father died of tuberculosis, leaving the family with just eight dollars. Frost's mother died of cancer in 1900. In 1920, he had to commit his younger sister Jeanie to a mental hospital, where she died nine years later. Mental illness apparently ran in Frost's family, as both he and his mother suffered from depression, and his daughter Irma was committed to a mental hospital in 1947. Frost's wife, Elinor, also experienced bouts of depression.[22]

Elinor and Robert Frost had six children: son Elliott (1896–1900, died of cholera); daughter Lesley Frost Ballantine (1899–1983); son Carol (1902–1940); daughter Irma (1903–1967); daughter Marjorie (1905–1934, died as a result of puerperal fever after childbirth); and daughter Elinor Bettina (died just one day after her birth in 1907). Only Lesley and Irma outlived their father. Frost's wife, who had heart problems throughout her life, developed breast cancer in 1937 and died of heart failure in 1938.[22]

Work

Style and critical reception

Critic Harold Bloom argued that Frost was one of "the major American poets".[31]

Randall Jarrell's influential essays on Frost include "Robert Frost's 'Home Burial'" (1962), an extended close reading of that particular poem,[32] and "To The Laodiceans", (1952) in which Jarrell defended Frost against critics who had accused Frost of being too "traditional" and out of touch with Modern or Modernist poetry. Jarrell wrote "the regular ways of looking at Frost's poetry are grotesque simplifications, distortions, falsifications—coming to know his poetry well ought to be enough, in itself, to dispel any of them, and to make plain the necessity of finding some other way of talking about his work." Jarrell's close readings of poems like "Neither Out Too Far Nor In Too Deep" led readers and critics to perceive more of the complexities in Frost's poetry.

Brad Leithauser notes that "the 'other' Frost that Jarrell discerned behind the genial, homespun New England rustic—the 'dark' Frost who was desperate, frightened, and brave—has become the Frost we've all learned to recognize, and the little-known poems Jarrell singled out as central to the Frost canon are now to be found in most anthologies".[33][34] Jarrell lists a selection of the Frost poems he considers the most masterful, including "The Witch of Coös", "Home Burial", "A Servant to Servants", "Directive", "Neither Out Too Far Nor In Too Deep", "Provide, Provide", "Acquainted with the Night", "After Apple Picking", "Mending Wall", "The Most of It", "An Old Man's Winter Night", "To Earthward", "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening", "Spring Pools", "The Lovely Shall Be Choosers", "Design" and "Desert Places".[35]

I'd like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth's the right place for love:

I don't know where it's likely to go better.

I'd like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

Robert Frost

In 2003, the critic Charles McGrath noted that critical views on Frost's poetry have changed over the years (as has his public image). In "The Vicissitudes of Literary Reputation," McGrath wrote, "Robert Frost ... at the time of his death in 1963 was generally considered to be a New England folkie ... In 1977, the third volume of Lawrance Thompson's biography suggested that Frost was a much nastier piece of work than anyone had imagined; a few years later, thanks to the reappraisal of critics like William H. Pritchard and Harold Bloom and of younger poets like Joseph Brodsky, he bounced back again, this time as a bleak and unforgiving modernist."[37]

In The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, editors Richard Ellmann and Robert O'Clair compared and contrasted Frost's unique style to the work of the poet Edwin Arlington Robinson since they both frequently used New England settings for their poems. However, they state that Frost's poetry was "less [consciously] literary" and that this was possibly due to the influence of English and Irish writers like Thomas Hardy and W. B. Yeats. They note that Frost's poems "show a successful striving for utter colloquialism" and always try to remain down to earth, while at the same time using traditional forms, despite the trend of American poetry towards free verse, which Frost famously said was "'like playing tennis without a net.'"[38][39]

The Poetry Foundation makes the same point, placing Frost's work "at the crossroads of nineteenth-century American poetry [with regard to his use of traditional forms] and modernism [with his use of idiomatic language and ordinary, everyday subject matter]." They also note that Frost believed that "the self-imposed restrictions of meter in form" was more helpful than harmful because he could focus on the content of his poems instead of concerning himself with creating "innovative" new verse forms.[40]

An earlier study by the poet James Radcliffe Squires spoke to the distinction of Frost as a poet whose verse soars more for the difficulty and skill by which he attains his final visions, than for the philosophical purity of the visions themselves. "He has written at a time when the choice for the poet seemed to lie among the forms of despair: Science, solipsism, or the religion of the past century ... Frost has refused all of these and in the refusal has long seemed less dramatically committed than others ... But no, he must be seen as dramatically uncommitted to the single solution ... Insofar as Frost allows to both fact and intuition a bright kingdom, he speaks for many of us. Insofar as he speaks through an amalgam of senses and sure experience so that his poetry seems a nostalgic memory with overtones touching some conceivable future, he speaks better than most of us. That is to say, as a poet must."[41]

The classicist Helen H. Bacon has proposed that Frost's deep knowledge of Greek and Roman classics influenced much of his work. Frost's education at Lawrence High School, Dartmouth, and Harvard "was based mainly on the classics". As examples, she links imagery and action in Frost's early poems "Birches" (1915) and "Wild Grapes" (1920) with Euripides' Bacchae. She cites certain motifs, including that of the tree bent down to earth, as evidence of his "very attentive reading of Bacchae, almost certainly in Greek". Bacon compares the poetic techniques used by Frost in "One More Brevity" (1953) to those of Virgil in the Aeneid. She notes that "this sampling of the ways Frost drew on the literature and concepts of the Greek and Roman world at every stage of his life indicates how imbued with it he was".[42]

Themes

In Contemporary Literary Criticism, the editors state that "Frost's best work explores fundamental questions of existence, depicting with chilling starkness the loneliness of the individual in an indifferent universe."[43] The critic T. K. Whipple focused on this bleakness in Frost's work, stating that "in much of his work, particularly in North of Boston, his harshest book, he emphasizes the dark background of life in rural New England, with its degeneration often sinking into total madness."[43]

In sharp contrast, the founding publisher and editor of Poetry, Harriet Monroe, emphasized the folksy New England persona and characters in Frost's work, writing that "perhaps no other poet in our history has put the best of the Yankee spirit into a book so completely."[43] She notes his frequent use of rural settings and farm life, and she likes that in these poems, Frost is most interested in "showing the human reaction to nature's processes." She also notes that while Frost's narrative, character-based poems are often satirical, Frost always has a "sympathetic humor" towards his subjects.[43]

Influenced by

- Robert Graves

- Rupert Brooke

- Thomas Hardy[38]

- William Butler Yeats[38]

- John Keats

- Ralph Waldo Emerson[44]

Influenced

Awards and recognition

Frost was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature 31 times.[46]

Harvard's 1965 alumni directory notes that Frost received an honorary degree there. Although he never graduated from college, Frost received over 40 honorary degrees, including from Princeton, Oxford and Cambridge universities, and became the only person to have received two honorary degrees from Dartmouth College. During his lifetime, the Robert Frost Middle School in Fairfax, Virginia, the Robert L. Frost School in Lawrence, Massachusetts, and the main library of Amherst College were named after him.

In 1960, Frost was awarded a United States Congressional Gold Medal, "In recognition of his poetry, which has enriched the culture of the United States and the philosophy of the world";[47] it was formally bestowed on him by John F. Kennedy in March 1962.[48] Also in 1962, he was awarded the Edward MacDowell Medal for outstanding contribution to the arts by the MacDowell Colony.[49]

In June 1922, the Vermont State League of Women's Clubs elected Frost as Poet Laureate of Vermont. When a New York Times editorial strongly criticized the decision of the Women's Clubs, Sarah Cleghorn and other women wrote to the newspaper defending Frost.[50] Frost was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1931 and the American Philosophical Society in 1937.[51][52] On July 22, 1961, Frost was named Poet Laureate of Vermont by the state legislature through Joint Resolution R-59 of the Acts of 1961, which also created the position.[53][54][55][56] Frost won the 1963 Bollingen Prize.

Pulitzer Prizes

- 1924 for New Hampshire: A Poem With Notes and Grace Notes

- 1931 for Collected Poems

- 1937 for A Further Range

- 1943 for A Witness Tree

Legacy and cultural influence

- Robert Frost Hall is an academic building at Southern New Hampshire University in Manchester, New Hampshire.[57]

- In the early morning of November 23, 1963, Westinghouse Broadcasting's Sid Davis reported the arrival of President John F. Kennedy's casket at the White House. Since Frost was one of the President's favorite poets, Davis concluded his report with a passage from "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening", but was overcome with emotion as he signed off.[58][59]

- Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964), the first Prime Minister of India, had kept a book of Robert Frost's close to him towards his later years, even at his bedside table as he lay dying.[60]

- The poem "Nothing Gold Can Stay" is featured in both the 1967 novel The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton and the 1983 film adaptation, first recited aloud by the character Ponyboy to his friend Johnny. In a subsequent scene Johnny quotes a stanza from the poem back to Ponyboy by means of a letter which was read after he passes away.

- His poem "Fire and Ice" influenced the title and other aspects of George R. R. Martin's fantasy series A Song of Ice and Fire.[61][62]

- Nothing Gold Can Stay is the name of the debut studio album by American pop-punk band New Found Glory, released on October 19, 1999.[63]

- At the funeral of former Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau, on October 3, 2000, his eldest son Justin rephrased the last stanza of the poem "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" in his eulogy: "The woods are lovely, dark and deep. He has kept his promises and earned his sleep."[64]

- A Garfield comic strip published on October 20, 2002, originally featured the titular character reciting "Nothing Gold Can Stay".[65] However, this was replaced in book collections and online edition,[66] likely due to the poem being still under copyright when the comic ran (the poem has since lapsed into public domain, in 2019).[67]

- The poem "Fire and Ice" is the epigraph of Stephenie Meyer's 2007 book, Eclipse, of the Twilight Saga. It is also read by Kristen Stewart's character, Bella Swan, at the beginning of the 2010 Eclipse film.

- "Nothing Gold Can Stay" is referenced in First Aid Kit's 2014 album Stay Gold: "But just as the moon it shall stray / So dawn goes down today / No gold can stay / No gold can stay."[68]

- "Nothing Gold Can Stay" (February 4, 2015) is the title given to the tenth episode of the seventh season of The Mentalist in which a character is killed.

- The character of Baron Quinn recites "Fire and Ice" in an episode of AMC's Into the Badlands.

- Verses of "Fire and Ice" are referenced and recited throughout the 2017 episodic video game Life Is Strange: Before the Storm.

- The line "Nothing gold can stay" is featured in the 2018 single "Venice Bitch" by American singer Lana Del Rey.[69] Del Rey also previously used this line in her 2015 single "Music to Watch Boys To".[70]

One of the original collections of Frost materials, which he personally helped compile, is held in the Special Collections department of the Jones Library in Amherst, Massachusetts. The collection consists of approximately twelve thousand items, including original manuscript poems and letters, correspondence, photographs, and audio and visual recordings.[71] The Archives and Special Collections at Amherst College holds a small collection of his papers. The University of Michigan Library holds the Robert Frost Family Collection of manuscripts, photographs, printed items, and artwork.[72] The most significant collection of Frost's working manuscripts is held by Dartmouth.

Selected works

Poetry collections

- 1913. A Boy's Will. London: David Nutt (New York: Holt, 1915)[73]

- 1914. North of Boston. London: David Nutt (New York: Holt, 1914)

- 1916. Mountain Interval. New York: Holt

- 1923. Selected Poems. New York: Holt.

- "The Runaway"

- Also includes poems from first three volumes

- 1923. New Hampshire. New York: Holt (London: Grant Richards, 1924)

- 1924. Several Short Poems. New York: Holt[74]

- 1928. Selected Poems. New York: Holt.

- 1928. West-Running Brook. New York: Holt

- 1929. The Lovely Shall Be Choosers, The Poetry Quartos, printed and illustrated by Paul Johnston. Random House.

- 1930. Collected Poems of Robert Frost. New York: Holt (UK: Longmans Green, 1930)

- 1933. The Lone Striker. US: Knopf

- 1934. Selected Poems: Third Edition. New York: Holt

- 1935. Three Poems. Hanover, NH: Baker Library, Dartmouth College.

- 1935. The Gold Hesperidee. Bibliophile Press.

- 1936. From Snow to Snow. New York: Holt.

- 1936. A Further Range. New York: Holt (Cape, 1937)

- 1939. Collected Poems of Robert Frost. New York: Holt (UK: Longmans, Green, 1939)

- 1942. A Witness Tree. New York: Holt (Cape, 1943)

- 1943. Come In, and Other Poems. New York: Holt.

- 1947. Steeple Bush. New York: Holt

- 1949. Complete Poems of Robert Frost. New York: Holt (Cape, 1951)

- 1951. Hard Not To Be King. House of Books.

- 1954. Aforesaid. New York: Holt.

- 1959. A Remembrance Collection of New Poems. New York: Holt.

- 1959. You Come Too. New York: Holt (UK: Bodley Head, 1964)

- 1962. In the Clearing. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston

- 1969. The Poetry of Robert Frost. New York: Holt Rinehart & Winston.

Plays

- 1929. A Way Out: A One Act Play (Harbor Press).

- 1929. The Cow's in the Corn: A One Act Irish Play in Rhyme (Slide Mountain Press).

- 1945. A Masque of Reason (Holt).

- 1947. A Masque of Mercy (Holt).

Letters

- 1963. The Letters of Robert Frost to Louis Untermeyer (Holt, Rinehart & Winston; Cape, 1964).

- 1963. Robert Frost and John Bartlett: The Record of a Friendship, by Margaret Bartlett Anderson (Holt, Rinehart & Winston).

- 1964. Selected Letters of Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston).

- 1972. Family Letters of Robert and Elinor Frost (State University of New York Press).

- 1981. Robert Frost and Sidney Cox: Forty Years of Friendship (University Press of New England).

- 2014. The Letters of Robert Frost, Volume 1, 1886–1920, edited by Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, and Robert Faggen. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674057609. (811 pages; first volume, of five, of the scholarly edition of the poet's correspondence, including many previously unpublished letters.)

- 2016. The Letters of Robert Frost, Volume 2, 1920–1928, edited by Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, Robert Bernard Hass, and Henry Atmore. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674726642. (848 pages; second volume of the series.)

- 2021. The Letters of Robert Frost, Volume 3, 1929–1936, edited by Mark Richardson, Donald Sheehy, Robert Bernard Hass, and Henry Atmore. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674726659. (848 pages; third volume of the series.)

Other

- 1957. Robert Frost Reads His Poetry. Caedmon Records, TC1060. (spoken word)

- 1966. Interviews with Robert Frost (Holt, Rinehart & Winston; Cape, 1967).

- 1995. Collected Poems, Prose and Plays, edited by Richard Poirier. Library of America. ISBN 978-1-883011-06-2. (omnibus volume.)

- 2007. The Notebooks of Robert Frost, edited by Robert Faggen. Harvard University Press.[75]

See also

- List of poems by Robert Frost

- Frostiana

- New Hampshire Historical Marker No. 126: Robert Frost 1874–1963

Citations

- ^ "Robert Frost". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ a b "Robert Frost". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online ed.). 2008. Retrieved December 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "Robert Frost". Poetry Foundation. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Jean C. Stine, Bridget Broderick, and Daniel G. Marowski. Vol. 26. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983. p 110.

- ^ Jarrell, Randall. "Fifty Years of American Poetry." No Other Book: Selected Essays. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

- ^ Joyce Carol Oates, ed. (2000). The Best American Essays of the Century. p. 176.

- ^ Watson, Marsten. Royal Families - Americans of Royal and Noble Ancestry. Volume Three: Samuel Appleton and His Wife Judith Everard and Five Generations of Their Descendants. 2010.

- ^ Rothman, Joshua (January 29, 2013) [January 29, 2013]. "Robert Frost: Darkness or Light?". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Archived from the original on October 19, 2023. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Ehrlich, Eugene; Carruth, Gorton (1982). The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States. Vol. 50. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-503186-5.

- ^ Nancy Lewis Tuten; John Zubizarreta (2001). The Robert Frost encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-313-29464-8.

Halfway through the spring semester of his second year, Dean Briggs released him from Harvard without prejudice, lamenting the loss of so good a student.

- ^ Jay Parini (2000). Robert Frost: A Life. Macmillan. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-8050-6341-7.

- ^ Jeffrey Meyers (1996). Robert Frost: a biography. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395856031.

Frost remained at Harvard until March of his sophomore year, when he decamped in the middle of a term ...

- ^ Orr, David (August 18, 2015). The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong. Penguin. ISBN 9780698140899.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (1996). Robert Frost: A Biography. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 107–109. ISBN 9780395728093.

- ^ "Phi Beta Kappa Authors". The Phi Beta Kappa Key. 6 (4): 237–240. 1926. JSTOR 42914052.

- ^ a b c "Resource: Voices & Visions". www.learner.org. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "The 1924 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Poetry". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "The 1931 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Poetry". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "The 1937 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Poetry". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "The 1943 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Poetry". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Bread Loaf School of English". Middlebury Bread Loaf School of English. Retrieved February 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Frost, Robert (1995). Poirier, Richard; Richardson, Mark (eds.). Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. The Library of America. Vol. 81. New York: Library of America. ISBN 1-883011-06-X.

- ^ a b "Robert Frost Stone House Museum | Bennington College". www.bennington.edu.

- ^ a b c d Muir, Helen (1995). Frost in Florida: a memoir. Valiant Press. pp. 11, 17. ISBN 0-9633461-6-4.

- ^ "John F. Kennedy: A Man of This Century". CBS. November 22, 1963.

- ^ "The Poet - Politician - JFK The Last Speech". JFK The Last Speech. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Udall, Stewart L. (June 11, 1972). "Robert Frost's Last Adventure". archive.nytimes.com. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "When Robert Frost met Khrushchev". Christian Science Monitor. April 8, 2008. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Schachter, Aaron (August 10, 2018). "Remembering John F. Kennedy's Last Speech". All Things Considered. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ "Robert Frost Dies at 88; Kennedy Leads in Tribute". The New York Times. Associated Press. January 30, 1963. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1999). Robert Frost. Chelsea House. p. 9.

- ^ Jarrell, Randall (1999) [1962]. "On 'Home Burial'". English Department at the University of Illinois. Archived from the original on October 2, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2018.

- ^ Leithauser, Brad. Introduction. No Other Book: Selected Essays. New York: HarperCollins, 1999.

- ^ Nelson, Cary (2000). Anthology of Modern American Poetry. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0-19-512270-4.

- ^ Jarrell, Randall. "Fifty Years of American Poetry." No Other Book: Selected Essays. HarperCollins, 1999.

- ^ "Birches by Robert Frost". The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved February 18, 2015.

- ^ McGrath, Charles. "The Vicissitudes of Literary Reputation." The New York Times Magazine. June 15, 2003.

- ^ a b c Ellman, Richard and Robert O'Clair. The Norton Anthology of Modern Poetry, Second Edition. New York: Norton, 1988.

- ^ Faggen, Robert (2001). Editor (First ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Robert Frost". Poetry Foundation. March 21, 2018. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ Squires, Radcliffe. The Major Themes of Robert Frost, The University of Michigan Press, 1963, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Bacon, Helen. "Frost and the Ancient Muses." The Cambridge Companion to Robert Frost. Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 75–99.

- ^ a b c d Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Jean C. Stine, Bridget Broderick, and Daniel G. Marowski. Vol. 26. Detroit: Gale Research, 1983, pp. 110–129.

- ^ Crawley, Mary (Fall 2007). "Troubled Thoughts about Freedom: Frost, Emerson, and National Identity". The Robert Frost Review. 17 (17): 27–41. JSTOR 24727384.

- ^ Foundation, Poetry (March 16, 2019). "Edward Thomas". Poetry Foundation.

- ^ "Nomination Archive". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ "Office of the Clerk – U.S. House of Representatives, Congressional Gold Medal Recipients". Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- ^ Parini, Jay (1999). Robert Frost: A Life. New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 408, 424–425. ISBN 9780805063417.

- ^ "The MacDowell Colony – Medal Day". Archived from the original on November 6, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Robert Frost (2007). The Collected Prose of Robert Frost. Harvard University Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-674-02463-2.

- ^ "Robert Lee Frost". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved May 23, 2023.

- ^ Nancy Lewis Tuten; John Zubizarreta (2001). The Robert Frost Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-313-29464-8.

- ^ Deirdre J. Fagan (January 1, 2009). Critical Companion to Robert Frost: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. Infobase Publishing. p. 249. ISBN 978-1-4381-0854-4.

- ^ Vermont. Office of Secretary of State (1985). Vermont Legislative Directory and State Manual: Biennial session. p. 19.

Joint Resolution R-59 of the Acts of 1961 named Robert Lee Frost as Vermont's Poet Laureate. While not a native Vermonter, this eminent American poet resided here throughout much of his adult ...

- ^ Vermont Legislative Directory and State Manual. Secretary of State. 1989. p. 20.

The position was created by Joint Resolution R-59 of the Acts of 1961, which designated Robert Frost state poet laureate.

- ^ "History". Southern New Hampshire University. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ "My Brush with History - "We Heard the Shots …": Aboard the Press Bus in Dallas 40 Years Ago" (PDF). med.navy.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2013.

- ^ Davis, Sid; Bennett, Susan; Trost, Catherine ‘Cathy’; Rather, Daniel ‘Dan’ Irvin Jr (2004). "Return To The White House". President Kennedy Has Been Shot: Experience The Moment-to-Moment Account of The Four Days That Changed America. Newseum (illustrated ed.). Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks. p. 173. ISBN 1-4022-0317-9. Retrieved December 10, 2011 – via Google Books.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "And miles to go before I sleep". October 9, 2011.

- ^ "George R.R. Martin: "Trying to please everyone is a horrible mistake"". www.adriasnews.com. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "Five Fascinating Facts about Game of Thrones". Interesting Literature. May 6, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ "MUSIC | New Found Glory". www.newfoundglory.com. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ "Justin Trudeau's eulogy". On This Day. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: CBC Radio. October 3, 2000. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ "No. 2799: Original, Original Strip". mezzacotta. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ "Daily Comic Strip on October 20th, 2002". Garfield.com.

- ^ "Robert Frost – 5 Poems from NEW HAMPSHIRE (Newly released to the Public Domain)". Englewood Review of Books. February 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- ^ Stephen M. Deusner (June 12, 2014). "First Aid Kit: Stay Gold Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved October 6, 2016.

- ^ "Lana Del Rey – Venice Bitch Lyrics | Genius Lyrics". Genius.com. September 17, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ "Lana Del Rey – Music To Watch Boys To Lyrics | Genius Lyrics". Genius.com. Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Robert Frost Collection". Jones Library, Inc. website, Amherst, Massachusetts. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ "Robert Frost Family Collection 1923-1988".

- ^ "Robert Frost. 1915. A Boy's Will". www.bartleby.com. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Frost, Robert (March 16, 1924). Several short poems. Place of publication not identified. OCLC 1389446.

- ^ "Browse Subjects, Series, and Libraries | Harvard University Press". www.hup.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on March 15, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

General sources

- Pritchard, William H. (2000). "Frost's Life and Career". Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved March 18, 2001.

- Taylor, Welford Dunaway (1996). Robert Frost and J. J. Lankes: Riders on Pegasus. Hanover, New Hampshire: Dartmouth College Library. OCLC 1036107807.

- "Vandalized Frost house drew a crowd". Burlington Free Press, January 8, 2008.

- Robert Frost (1995). Collected Poems, Prose, & Plays. Edited by Richard Poirier and Mark Richardson. Library of America. ISBN 1-883011-06-X (trade paperback).

- Robert Frost Biographical Information

External links

- Robert Frost: Profile, Poems, Essays at Poets.org

- Robert Frost, profile and poems at the Poetry Foundation

- Profile (Archived July 2, 2022, at the Wayback Machine) at Modern American Poetry

- Richard Poirier (Summer–Fall 1960). "Robert Frost, The Art of Poetry No. 2". The Paris Review. Summer-Fall 1960 (24).

- Robert Frost Collection Archived October 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine and Lawrence H. Conrad Collection of Vachel Lindsay and Robert Frost Material in Archives and Special Collections, Amherst College, Amherst, MA

- Robert Frost at Bread Loaf (Middlebury College). Archived May 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- Robert Frost Farm in Derry, NH

- The Frost Place Archived June 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine – a museum and poetry conference center in Franconia, N.H.

- Yale College Lecture on Robert Frost – audio, video and full transcripts of Open Yale Courses

- Robert Frost Declares Himself a "Balfour Israelite" and Discusses His Trip to the Western Wall

- Drawing of Robert Frost by Wilfred Byron Shaw[permanent dead link] at University of Michigan Museum of Art

Libraries

- Robert Frost Collection in Special Collections, Jones Library, Amherst, MA

- Robert Frost book collection and Robert Frost papers at the University of Maryland Libraries

- The Victor E. Reichert Robert Frost Collection from the University at Buffalo Libraries Poetry Collection

- Robert Frost Collection at Dartmouth College Library

Electronic editions

- Works by Robert Frost in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Robert Frost at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Robert Frost at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Robert Frost at the Internet Archive

- Robert Frost reading his poems at Harper Audio (recordings from 1956)

- Works by Robert Frost at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Robert Frost

- 1874 births

- 1963 deaths

- 19th-century American poets

- 20th-century American poets

- American Poets Laureate

- American male poets

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- Amherst College faculty

- Bollingen Prize recipients

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Dartmouth College alumni

- Formalist poets

- Harvard University alumni

- Harvard University faculty

- Middlebury College faculty

- People from Bennington, Vermont

- People from Derry, New Hampshire

- People from Franconia, New Hampshire

- Writers from Lawrence, Massachusetts

- Phillips family (New England)

- Plymouth State University people

- Poets Laureate of Vermont

- Poets from California

- Poets from Massachusetts

- Poets from New Hampshire

- Poets from Vermont

- Pulitzer Prize for Poetry winners

- Sonneteers

- University of Michigan faculty

- Writers from San Francisco

- American inaugural poets

- 20th-century American male writers

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- Members of the American Philosophical Society