Endoskeleton

| Part of a series related to |

| Biomineralization |

|---|

|

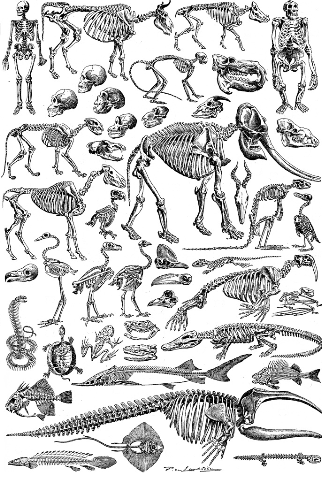

An endoskeleton (From Greek ἔνδον, éndon = "within", "inner" + σκελετός, skeletos = "skeleton") is a structural frame (skeleton) on the inside of an animal, overlaid by soft tissues and usually composed of mineralized tissue.[1][2] Endoskeletons serve as structural support against gravity and mechanical loads, and provide anchoring attachment sites for skeletal muscles to transmit force and allow movements and locomotion.

Vertebrates and the closely related cephalochordates are the predominant animal clade with endoskeletons (made of mostly bone and sometimes cartilage), although invertebrates such as sponges also have evolved a form of endoskeletons made of diffuse meshworks of calcite/silica structural elements called spicules, and echinoderms have a dermal calcite endoskeleton known as ossicles. Some coleoid cephalopods (squids and cuttlefish) have an internalized vestigial aragonite/calcite-chitin shell known as gladius or cuttlebone, which can serve as muscle attachments but the main function is often to maintain buoyancy rather than to give structural support, and their body shape is largely maintained by hydroskeleton.

Compared to the exoskeletons of many invertebrates, endoskeletons allow much larger overall body sizes for the same skeletal mass, as most soft tissues and organs are positioned outside the skeleton rather than within it. Being more centralized in structure also means more compact volume, making it easier for the circulatory system to perfuse and oxygenate, as well as higher tissue density against stress. The external nature of muscle attachments also allows thicker and more diverse muscle architectures, as well as more versatile range of motions.

Overview

[edit]An endoskeleton is a skeleton that is on the inside of a body, like humans, dogs, or some fish. The endoskeleton develops within the skin or in the deeper body tissues. The vertebrate endoskeleton is basically made up of two types of tissues (bone and cartilage). During early embryonic development the endoskeleton is composed of notochord and cartilage. The notochord in most vertebrates is replaced by the vertebral column and cartilage is replaced by bone in most adults. In three phyla and one subclass of animals, endoskeletons of various complexity are found: Chordata, Echinodermata, Porifera, and Coleoidea. An endoskeleton may function purely for support (as in the case of sponges), but often serves as an attachment site for muscle and a mechanism for transmitting muscular forces. A true endoskeleton is derived from mesodermal tissue. Such a skeleton is present in echinoderms and chordates. The poriferan "skeleton" consists of microscopic calcareous or siliceous spicules or a spongin network. The Coleoidea do not have a true endoskeleton in the evolutionary sense; there, a mollusk exoskeleton evolved into several sorts of internal structure, the "cuttlebone" of cuttlefish being the best-known version. Yet they do have cartilaginous tissue in their body, even if it is not mineralized, especially in the head, where it forms a primitive cranium. The endoskeleton gives shape, support, and protection to the body and provides a means of locomotion.

-

A human skeleton on display at Booth Museum of Natural History

-

Fossilized skeleton of various dinosaurs

-

The skeleton of a kitefin shark, a cartilaginous fish

-

The dermal ossicles of a starfish, an echinoderm

-

The silica spicule skeleton of a Venus' flower basket, a glass sponge

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Hyman, Libbie Henrietta (1992-09-15). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 192–236. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7.

- ^ Gillis, J. Andrew (2019), "The Development and Evolution of Cartilage", Reference Module in Life Sciences, Elsevier, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-809633-8.90770-2, ISBN 978-0-12-809633-8, retrieved 2023-10-03