Bishop Museum

Bishop Museum | |

The Hawaiian Hall at the Bishop Museum contains the world's largest collection of Polynesian artifacts. | |

| Location | 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawaii |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 21°20′00.0″N 157°52′14.2″W / 21.333333°N 157.870611°W |

| Built | 1889 |

| Architect | William F. Smith |

| Architectural style | Richardsonian Romanesque |

| Website | www |

| NRHP reference No. | 82002500[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 26, 1982 |

The Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, designated the Hawaiʻi State Museum of Natural and Cultural History, is a museum of history and science in the historic Kalihi district of Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of Oʻahu. Founded in 1889, it is the largest museum in Hawaiʻi and has the world's largest collection of Polynesian cultural artifacts and natural history specimens. Besides the comprehensive exhibits of Hawaiian cultural material, the museum's total holding of natural history specimens exceeds 24 million,[2] of which the entomological collection alone represents more than 13.5 million specimens (making it the third-largest insect collection in the United States). The Index Herbariorum code assigned to Herbarium Pacificum of this museum is BISH[3] and this abbreviation is used when citing housed herbarium specimens.

The museum complex is home to the Richard T. Mamiya Science Adventure Center.

History

[edit]Establishment

[edit]

Charles Reed Bishop (1822–1915), a businessman and philanthropist, co-founder of the First Hawaiian Bank and Kamehameha Schools, built the museum in memory of his late wife, Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop (1831–1884). Born into the royal family, she was the last legal heir of the Kamehameha Dynasty, which had ruled the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi between 1810 and 1872. Bishop had originally intended the museum to house family heirlooms passed down to him through the royal lineage of his wife.

Bishop hired William Tufts Brigham as the first curator of the museum; Brigham later served as director from 1898 until his retirement in 1918.

The museum was built on the original boys' campus of Kamehameha Schools, an institution created at the bequest of the Princess, to benefit native Hawaiian children; she gave details in her last will and testament. In 1898, Bishop had Hawaiian Hall and Polynesian Hall built on the campus, in the popular Richardsonian Romanesque architectural style. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser newspaper dubbed these two structures as "the noblest buildings of Honolulu".

Today both halls are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Hawaiian Hall is home to a complete sperm-whale skeleton, accompanied by a papier-mâché body suspended above the central gallery. Along the walls are prized koa wood display cases; today this wood in total is worth more than the original Bishop Museum buildings.

The museum is accessible on public transit: TheBus Routes A, 1, 2, 7, 10.

Kaimiloa Expedition

[edit]In 1924, American millionaire, Medford Ross Kellum, outfitted a four masted barquentine for a scientific expedition which, even the naming of the ship Kaimiloa, was left entirely to the scientific circles of Honolulu.[4]

The goal of the expedition was a five-year exploration of many of the then inaccessible spots of the Pacific. Under the auspices of the Bishop Museum, a group of Hawaiʻi scientists joined the ship: Gerrit P. Wilder, botanist; Mrs. Wilder, historian; Kenneth Emory, ethnologist; Dr. Armstrong Sperry, writer and illustrator; and Dr. Stanley Ball.

The vessel was a complete floating laboratory, possibly the most complete of any craft that has undertaken a similar trip. Bottles, crates, and boxes were stowed below, along with gallons of preservatives for insects and plant specimens for the Bishop Museum. The goals of the expedition were exhaustive:

- complete collections of islands subjects ranging from insects, plants, minerals, and archaeological and ethnological specimens,

- study of the fish and sea life,

- chart as accurately as possible the ocean currents,

- for the United States government, conform and correct to the findings of the expedition the charts of the island groups,

- attempt to trace the origin of the Polynesians, their language and their migrations,

- photograph the natives and measure accurately portions of their bodies,

- record phonographically records of the speech, the songs, their chants,

- sound the ocean floor and study the formation of the islands in an effort to prove the unfounded but at the time prevalent theory that some Pacific islands were once a part of the mainland and that they formed a "lost continent".[5]

Later development

[edit]In 1940, Kamehameha Schools moved to its new campus in Kapālama, allowing the museum to expand at the original campus site. Bishop Hall, first built for use by the school, was adapted for museum use.[6] Most other school structures were razed, and new museum facilities were constructed. By the late 1980s, the Bishop Museum had become the largest natural and cultural history institution in Polynesia.

In 1988, construction of the Castle Memorial Building was begun. Dedicated on January 13, 1990, Castle Memorial Building houses all the major traveling exhibits that come to the Bishop Museum from institutions around the world.

The Richard T. Mamiya Science Adventure Center opened in November 2005. The building is designed as a learning center for children, and includes many interactive exhibits focused on marine science, volcanology, and related sciences.[7][8]

Library and archives

[edit]The museum library has one of the most extensive collections of books, periodicals, newspapers and special collections concerned with Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. The archives hold the results of extensive studies done by museum staff in the Pacific Basin, as well as manuscripts, photographs, artwork, oral histories, commercial sound recordings and maps.

When Bishop Museum opened to the public in June 1891, its library consisted of but a few shelves of books in what is today the Picture Gallery.[9]

Many of Hawaiʻi's royalty, including Bernice Pauahi Bishop and Queen Liliʻuokalani, deposited their personal papers at Bishop Museum. Manuscripts in the collection also include scientific papers, genealogical records, and memorabilia.

The book collection consists of approximately 50,000 volumes with an emphasis on the cultural and natural history of Hawaiʻi and the Pacific, with subject strengths in anthropology, music, botany, entomology, and zoology. The library provides extra access to the collection of published diaries, narratives, memoirs, and other writings relating to 18th- and 19th-century Hawaiʻi.

Institutions

[edit]On the campus of Bishop Museum is the Jhamandas Watumull Planetarium, an educational and research facility devoted to the astronomical sciences and the oldest planetarium in Polynesia.

Also on the campus is Pauahi Hall, home to the J. Linsley Gressit Center for Research in Entomology, which houses some 14 million prepared specimens of insects and related arthropods, including over 16,500 primary types. It is the third-largest entomology collection in the United States and the eighth-largest in the world. An active research facility, Pauahi Hall is not open to the public.

Nearby is Pākī Hall, home to the Hawaiʻi Sports Hall of Fame, a museum library and archives, which are open to the public.

In 1992, the Hawaii State legislature created the Hawaii Biological Survey (HBS) as a program of the Bishop Museum. The HBS surveys, collects, inventories, studies, and maintains the reference collection of every plant and animal found in Hawaiʻi. It currently holds more than 4 million specimens in its collections.

From 1988 until 2009, the Bishop Museum also administered the Hawaiʻi Maritime Center in downtown Honolulu.[10] Built on a former private pier of Honolulu Harbor for the royal family, the center was the premier maritime museum in the Pacific Rim with artifacts in relation to the Pacific whaling industry and the Hawaiʻi steamship industry.

On the Big Island of Hawaiʻi, the Bishop Museum administers the Amy B.H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden, specializing in indigenous Hawaiian plant life.

Since 1920, the Secretariat of the Pacific Science Association (PSA), founded that year as an independent regional, non-governmental, scholarly organization, has been based at Bishop Museum. It seeks to advance science and technology in support of sustainable development in the Asia-Pacific.

Falls of Clyde

[edit]

From 1968 until September 2008, the Bishop Museum owned the Falls of Clyde, the oldest sail-driven oil tanker, which was moored at the Hawaiʻi Maritime Center. In early 2007, the ship was closed to public tours for safety reasons and in order to facilitate repairs to the deteriorating tank, which frequently caused the ship to list (tilt) dramatically. Marine experts conducted a thorough inspection of the ship. Between 1998 and 2008 the museum incurred more than $2 million in preservation costs.[11]

The museum threatened to sink the ship by the end of 2008 unless private funds were raised for a perpetual care endowment.[12] On September 28, 2008, ownership was transferred to the non-profit group, Friends of Falls of Clyde, which intends to restore the ship.[13]

In October of that same year, the Bishop Museum was criticized for having raised $600,000 to preserve the ship, and spent only about half that on the ship, and that for sandblasting that was determined to damage the integrity of the vessel. The media also pointed out other questionable spending decisions.[14]

Gallery

[edit]-

Bishop Hall, 2010

-

Front end of Hawaiian Hall, 2010

-

Entrance to Hawaiian & Polynesian Hall, 1958

-

Staircase to Polynesian Hall, 2010

-

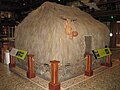

Hale pili in Hawaiian Hall, 2010

-

Sperm whale model in Hawaiian Hall, 2010

-

Hawaiian Girl with Dog, oil on canvas by John Mix Stanley, 1849

-

Hawaiian royalty wore these feathered cloaks (ʻahu ʻula) and helmets. The chief in the background is Kaʻiana.

-

Russian cannon outside the Bishop Museum in Honolulu in 1960

-

Entrance to the Amy Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden, 2011

-

Papua New Guinea Sawos people men's spirit house gable

-

Hawaiian Hall, with a heiau recreation in miniature (2012)

-

Atrium – photograph of Charles Bishop with Bernice Pauahi Bishop (2012)

-

Charles Bishop with his wife, Princess Bernice Pauahi, in the atrium of the museum (2012)

-

Kahili Room – Kahili Paʻa Lima in a glass case (2012)

-

Hawaiian Hall – akua kiʻi (2012)

-

Hawaiian Hall – hale replica with placard (2012)

Publications

[edit]- Bishop Museum Occasional Papers (1898–present)

- Bishop Museum Memoirs (1899–1949)

- Bishop Museum Bulletins (1922–present)

- Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology

- Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany

- Bishop Museum Bulletins in Cultural and Environmental Studies

- Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology

- Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology

- Bishop Museum Special Publications (1892–present)

- Bishop Museum Technical Reports (1992–present)

- Pacific Insects (1959–1983)

- International Journal of Entomology (1983–1985)

- Pacific Insects Monographs (1961–1986)

- Insects of Micronesia (1954–present)

- Journal of Medical Entomology (1964–1986, published by the Entomological Society of America, after 1986)

See also

[edit]- Mangarevan expedition, a 1934 scientific expedition sponsored by the Bishop Museum to investigate the natural history of the farthest southeastern islands of Polynesia

- Ray Jerome Baker, donor of a large collection of original prints, negatives, glass plate lantern slides, and ephemera

- Amy B. H. Greenwell Ethnobotanical Garden

- J. T. Gulick, an early evolution proponent who advanced concepts now known as genetic drift, anagenesis, cladogenesis, and speciation, sold his shell collection to the Bishop Museum.

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Research and Collections – Bishop Museum". Bishop Museum. Archived from the original on June 2, 2004.

- ^ "Index Herbariorum". Steere Herbarium, New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ "The Trustees and staff of the Museum are fairly bubbling with pleasure at finding that their dream of an exploring ship, reaching places otherwise inaccessible, has become a reality through interest of yourself and Mrs. Kellum. (...) It takes some talking to convince the trustees that you want your name submerged and that you don't care a whoop what the ship does or where it goes so long as you two friendly souls can render service by increasing knowledge of the Pacific." Director Gregory, Honolulu Museum, May 31, 1924.

- ^ "Adventurers to seek "lost continent in South Seas"". The Bulletin. San Francisco. October 11, 1924.

They are prepared to sit around the fire and listen to the ancient legends of the tribal chiefs of the great civilization that existed thousands— maybe million—of years ago; of the cities and the people.

- ^ "Aunty Pat Bacon Marks 50 Years at Bishop Museum". March 25, 2010. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Paiva, Derek (November 13, 2005). "Close encounters at new science center". The Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Alton, Helen (November 13, 2005). "Bishop Museum's Excellent Adventure: Its new $17 million science center draws kids into interactive exhibits exploring Hawaii's environment". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ "Library and Archives – Bishop Museum". Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Bishop Museum cutting hours, laying off and furloughing staff". Honolulu Advertiser. April 10, 2009. Retrieved February 2, 2021.

- ^ Fujimori, Leila (September 9, 2010). "Falls of Clyde backers committed to restoration". What ever Happened to... Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010.

- ^ Hall, Sabrina (February 22, 2008). "Falls of Clyde May Have Sinking Fate". KGMB9 News Hawaii. Honolulu, HI, USA: Raycom Media. Archived from the original on January 9, 2009. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ Bernardo, Rosemarie (September 27, 2008). "Museum to transfer historic ship". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

- ^ Pala, Christopher (October 18, 2008). "Historic Ship Stays Afloat, for Now". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2008.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Publications online

- Official website of the Amy B.H. Ethnobotanical Garden Archived September 4, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- J. Linsley Gressitt Center for Research in Entomology

- Pacific Science Association

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. HI-25, "Bishop Museum, Bishop Hall, Likelike Highway, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI", 2 photos, 1 photo caption page

- HABS No. HI-26, "Bishop Museum, Main Building, Likelike Highway, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI", 11 photos, 1 photo caption page

- Bishop Museum

- Hawaii culture

- Institutions accredited by the American Alliance of Museums

- Museums established in 1889

- Museums in Honolulu

- Educational buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Hawaii

- Museums on the National Register of Historic Places

- Richardsonian Romanesque architecture in Hawaii

- History museums in Hawaii

- Science museums in Hawaii

- Ethnic museums in Hawaii

- Natural history museums in Hawaii

- Art museums and galleries in Hawaii

- Natural Science Collections Alliance members

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Hawaii

- Pacific Islands-American culture in Honolulu

- Polynesian-American culture in Honolulu

- 1889 establishments in Hawaii

- National Register of Historic Places in Honolulu

- Bishop Museum academic journals