Stan Kenton

Stan Kenton | |

|---|---|

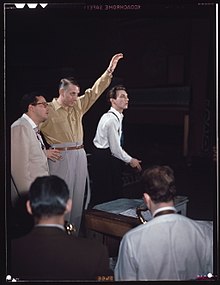

Kenton in January 1947 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Stanley Newcomb Kenton |

| Born | December 15, 1911 Wichita, Kansas, U.S. |

| Died | August 25, 1979 (aged 67) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instrument | Piano |

| Years active | 1930–1978 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

Stanley Newcomb Kenton (December 15, 1911 – August 25, 1979) was an American popular music and jazz artist. As a pianist, composer, arranger and band leader, he led an innovative and influential jazz orchestra for almost four decades. Though Kenton had several pop hits from the early 1940s into the 1960s, his music was always forward-looking. Kenton was also a pioneer in the field of jazz education, creating the Stan Kenton Jazz Camp in 1959 at Indiana University.[2]

Early life

[edit]Stan Kenton was born on December 15, 1911, in Wichita, Kansas; he had two sisters (Beulah and Erma Mae) born three and eight years after him, respectively. His parents, Floyd and Stella Kenton, moved the family to Colorado, and in 1924, to the Greater Los Angeles Area, settling in suburban Bell, California.[2]

Kenton attended Bell High School; his high-school yearbook picture has the prophetic notation "Old Man Jazz". Kenton started learning piano as a teen from a local pianist and organist. When he was around 15 and in high school, pianist and arranger Ralph Yaw introduced him to the music of Louis Armstrong and Earl Hines. He graduated from high school in 1930.

By the age of 16, Kenton was already playing a regular solo piano gig at a local hamburger eatery for 50 cents a night plus tips; during that time he had his own performing group named "The Bell-Tones". His first arrangement was written during this time for a local eight-piece band that played in nearby Long Beach.[2]

Career

[edit]1930s

[edit]With little money, Kenton traveled to speakeasys in San Diego and Las Vegas playing piano.[3] By 1932 he was playing with the Francis Gilbert Territory band and would tour through Arizona; he would go on to working with the Everett Hoagland Orchestra in 1933, which would be his first time playing at the Rendezvous Ballroom. He would then play with Russ Plummer, Hal Grayson and eventually got his big break with Gus Arnheim.[3]

In April 1936, Arnheim was reorganizing his band into the style of Benny Goodman's groups and Kenton was to take the piano chair. This is where Kenton would make his first recordings when Arnheim made 14 sides for the Brunswick label in summer of 1937. Once he departed from Gus Arnheim's group, Kenton went back to study with private teachers on both the piano and in composition. In 1938 Kenton would join Vido Musso in a short-lived band, but a very educational experience for him.

From the core of this group came the lineup of the first Stan Kenton groups of the 1940s. Kenton would also go on to working with the NBC House Band and in various Hollywood studios and clubs. Producer George Avakian took notice of Kenton during this time while he worked as the pianist and Assistant Musical Director at the Earl Carroll Theatre Restaurant in Hollywood. Kenton started to get the idea of running his own band from this experience; he created a rehearsal band of his own, which eventually become his group in the 1940s.[2]

1940s

[edit]

In 1940, Kenton formed his first orchestra. Kenton worked in the early days with his own groups as much more of an arranger than a featured pianist. Although there were no "name" musicians in his first band (with the possible exception of bassist Howard Rumsey and trumpeter Chico Alvarez), Kenton spent the summer of 1941 playing regularly before an audience at the Rendezvous Ballroom on the Balboa Peninsula at Newport Beach, CA. Influenced by Benny Carter and Jimmie Lunceford, the Stan Kenton Orchestra struggled for a time after its initial success. Its Decca recordings were not big sellers and a stint as Bob Hope's backup radio band during the 1943–44 season was an unhappy experience; Les Brown permanently took Kenton's place.[4]

Kenton's first appearance in New York was in February 1942 at the Roseland Ballroom, with the marquee featuring an endorsement by Fred Astaire.[5] By late 1943, with a contract with the newly formed Capitol Records, a popular record in "Eager Beaver", and growing recognition, the Stan Kenton Orchestra was gradually catching on; it developed into one of the best-known West Coast ensembles of the 1940s. Its soloists during the war years included Art Pepper, briefly Stan Getz, altoist Boots Mussulli, and singer Anita O'Day. By 1945, the band had evolved.[4] The songwriter Joe Greene provided the lyrics for hit songs like "And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine" and "Don't Let the Sun Catch You Cryin'".[6] Pete Rugolo became the chief arranger (extending Kenton's ideas), Bob Cooper and Vido Musso offered very different tenor styles, and June Christy was Kenton's new singer; her hits (including "Tampico" and Greene's "Across the Alley from the Alamo") made it possible for Kenton to finance his more ambitious projects.[citation needed]

Artistry in Rhythm

[edit]

When composer/arranger Pete Rugolo joined the Stan Kenton Orchestra as staff arranger in late 1945 he brought with him his love of jazz, Stravinsky and Bartók. Given free rein by Kenton, Rugolo experimented. Although Kenton himself was already trying experimental scores prior to Rugolo's tenure, it was Rugolo who brought extra jazz and classical influences much needed to move the band forward artistically.[citation needed]

During his first six months on the staff, Rugolo tried to copy Kenton's sound; on encouragement from the leader he explored his own voice. By incorporating compositional techniques borrowed from the modern classical music he studied, Rugolo was a key part of one of Kenton's most fertile and creative periods.[7]

After a string of mostly arrangements, Rugolo turned out three originals that Kenton featured on the band's first album in 1946 (Artistry in Rhythm): "Artistry in Percussion", "Safranski" and "Artistry in Bolero". Added to this mix came "Machito", "Rhythm Incorporated", "Monotony", and "Interlude" in early 1947 (although some were not recorded until later in the year). These compositions, along with June Christy's voice, came to define the Artistry in Rhythm band. Afro-Cuban writing was added to the Kenton book with compositions like Rugolo's "Machito". The resulting instrumentation, utilizing significant amounts of brass, was described as a "wall of sound" (a term later coined independently by Andrew Loog Oldham for Phil Spector's production methods).[8]

The Artistry in Rhythm ensemble was a formative band, with outstanding soloists. By early 1947, the Stan Kenton Orchestra had reached a high point of financial and popular success. They played in the best theaters and ballrooms in America and had numerous hit records. Dances at the ballrooms were typically four hours a night and theater dates generally involved playing mini-concerts between each showing of the movie. This was sometimes five or six a day, stretching from morning to late night. Most days not actually playing were spent in buses or cars. Days off from performing were rare. For Kenton they just allowed for more record signing, radio station interviews, and advertising for Capitol Records. Due to the financial and personal demands, following an April performance in Tuscaloosa, he broke up the Artistry in Rhythm incarnation of Kenton ensembles.[citation needed]

Progressive Jazz

[edit]After a hiatus of five months, Kenton formed a new, larger ensemble to present Concerts in Progressive Jazz. Sustaining the ensemble on its own proved mostly attainable but the band still had to fill in its schedule by booking dances and movie theater jobs, especially over the summer.[citation needed]

Pete Rugolo composed and arranged the great bulk of the new music; Kenton declared these works to be Progressive Jazz. A student of famed composer and educator Russ Garcia, Bob Graettinger wrote numerous works for the band, starting with his composition Thermopylae. His ground-breaking composition City of Glass was premiered by the band in Chicago in April 1948, but not recorded for another two and a half years, in a reworked version for the Innovations Orchestra. Ken Hanna, who began the tour as a trumpet player, contributed a few compositions to the new band, including Somnambulism. Kenton contributed no new scores to the Progressive Jazz band, although several of his older works were performed on concerts, including Concerto to End All Concertos, Eager Beaver, Opus in Pastels, and Artistry in Rhythm.[citation needed]

Cuban inflected titles from the Progressive Jazz period include Rugolo's Introduction to a Latin Rhythm, Cuban Carnival, The Peanut Vendor, Journey to Brazil, and Bob Graettinger's Cuban Pastorale. The addition of a full-time bongo player and a Brazilian guitarist in the band enabled Kenton's cadre of composers to explore Afro-Latin rhythms to far greater possibilities.[citation needed]

The Progressive Jazz period lasted 14 months, beginning on September 24, 1947, when the Stan Kenton Orchestra played a concert at the Rendezvous Ballroom. And it ended after the last show at the Paramount Theatre in New York City on December 14, 1948. The band produced only one album and a handful of singles, due to a recording ban by the American Federation of Musicians that lasted the entirety of 1948.[9]

The lone record, "A Presentation of Progressive Jazz",[10] received a 3 out of 4 rating from Tom Herrick in DownBeat.[11] Metronome rated it "C" calling it a "jerry-built jumble of effects and counter-effects" and "this album presents very little that can justifiably be called either jazz or progressive".[12] Billboard scored it 80 out of 100, but declared it "as mumbo-jumbo a collection of cacophony as has ever been loosed on an unsuspecting public.[13]

Many sidemen from the Artistry band returned, but there were significant changes.[14] Laurindo Almeida on classical guitar, and Jack Costanzo on bongos dramatically changed the band's timbre. Both were firsts for the Kenton band, or any jazz band for that matter. The rhythm section included returnees Eddie Safranski (bass) and Shelly Manne (drums), both destined to win first place Down Beat awards.[citation needed]

Kids are going haywire over the sheer noise of this band...There is a danger of an entire generation growing up with the idea that jazz and the atom bomb are essentially the same natural phenomenon.

— Barry Ulanov, Metronome, 1948[15]

Four of the five trumpet players returned: Buddy Childers, Ray Wetzel, Chico Alvarez, and Ken Hanna. Al Porcino was added to the already powerhouse section. Conte Candoli joined the band, replacing Porcino, in February 1948.[citation needed]

Kai Winding, star trombonist of the Artistry in Rhythm band, would not be a part of the Progressive Jazz era, except for a few dates on which he subbed. Milt Bernhart came in on lead trombone. And Bart Varsalona returned on bass trombone. Bernhart's first big solo with the Kenton band proved to be a major hit, The Peanut Vendor.[citation needed]

The saxophone section was much improved and modernized. Returning saxophonists included baritone Bob Gioga, holding down his chair since the very start, and Bob Cooper on tenor. With Vido Musso's departure, Cooper and his modernist sound became the featured tenor soloist. Art Pepper came on as second alto, the "jazz" chair. And the new lead alto was George Weidler.[citation needed]

This was genuinely a band of all-stars. They received five first place awards in the Down Beat poll at the end of 1947,[16] and similar awards from the other magazines. The arrangers continued to push the limits of these superb instrumentalists in their compositions. Works from this period are more sophisticated than those written for the Artistry band, and are some of the first and most successful "third stream" compositions.[citation needed]

The band criss-crossed the country, appearing in the nation's top concert venues, including Carnegie Hall, Boston Symphony Hall, Chicago Civic Opera House, Academy of Music (Philadelphia), and the Hollywood Bowl. They had extended stays at New York's Paramount Theatre and Hotel Commodore, Philadelphia's Click, Detroit's Eastwood Gardens, Radio City Theater in Minneapolis, and the Rendezvous Ballroom, a special place in Kenton's musical life.[citation needed]

Kenton's band was the first to present a concert in the famous outdoor arena, the Hollywood Bowl. His concert there on June 12, 1948, drew more than 15,000 people, and was both an artistic and commercial success. Kenton pocketed half of the box office, walking away with US$13,000 (equivalent to $164,859 in 2023) for the evening's concert.[17]

The band broke attendance records all across the country. Thanks to Kenton's public relations acumen, he was able to convince concert goers and record buyers of the importance of his music. Comedy numbers and June Christy vocals helped break up the seriousness of the new music.[citation needed]

Kenton's successes did not sit well with everyone. In an essay entitled Economics and Race in Jazz, Leslie B. Rout Jr. wrote:

"The real scourge of the 1946–1949 period was the all-white Stan Kenton band. Dubbing his musical repertoire progressive jazz, Kenton saw his orchestra become the first in jazz history to reach an annual gross of US$1,000,000 in 1948." (equivalent to $12.68 million in 2023)

— Leslie Rout (1968)[18]

Rout contrasted this with the relative lack of critical and public recognition for another leading jazz artist:

"Dizzy Gillespie as the premiere bopper could not be transformed into coin of the realm."

— Leslie Rout (1968)[18]

At the end of 1948, as the band was fulfilling an extended engagement at the Paramount Theater in New York City, the leader notified his sidemen, his bookers, and the press, that he would be disbanding once more. Kenton's most artistically and commercially successful band ceased to be at the top of their game. On December 14, 1948, the Stan Kenton Orchestra played their last notes for more than a year. They would return with new faces, new music, and a string section.[citation needed]

1950s

[edit]After a year's hiatus, in 1950 Kenton assembled the large 39-piece Innovations in Modern Music Orchestra that included 16 strings, a woodwind section, and two French horns. The music was an extension of the works composed and recorded since 1947 by Bob Graettinger, Manny Albam, Franklyn Marks and others. Name jazz musicians such as Maynard Ferguson, Shorty Rogers, Milt Bernhart, John Graas, Art Pepper, Bud Shank, Bob Cooper, Laurindo Almeida, Shelly Manne, and June Christy were part of these musical ensembles. The groups managed two tours during 1950–51, from a commercial standpoint it would be Stan Kenton's first major failure. Kenton soon reverted to a more standard 19-piece lineup.[2]

In order to be more commercially viable, Kenton reformed the band in 1951 to a much more standard instrumentation: five saxes, five trombones, five trumpets, piano, guitar, bass, drums. The charts of such arrangers as Gerry Mulligan, Johnny Richards, and particularly Bill Holman and Bill Russo began to dominate the repertoire. The music was written to better reflect the style of cutting edge, be-bop oriented big bands, such as those of Dizzy Gillespie or Woody Herman. Young, talented players and outstanding jazz soloists such as Maynard Ferguson, Lee Konitz, Conte Candoli, Sal Salvador, and Frank Rosolino made strong contributions to the level of the 1952–53 band. The music composed and arranged during this time was far more tailor-made to contemporary jazz tastes; the 1953 album New Concepts of Artistry in Rhythm is noted as one of the high points in Kenton's career as band leader. Though the band was to have a very strong "concert book", Kenton also made sure the dance book was made new, fresh and contemporary. The album Sketches on Standards from 1953 is an excellent example of Kenton appealing to a wider audience while using the band and Bill Russo's arranging skills to their fullest potential. Even though the personnel changed rather rapidly, Kenton's focus was very clear on where he would lead things musically. By this time producer Lee Gillette worked well in concert with Kenton to create a balanced set of recordings that were both commercially viable and cutting edge musically.

Arguably the most "swinging" band Kenton was to field came when legendary drummer Mel Lewis joined the orchestra in 1954. Kenton's Contemporary Concepts (1955) and Kenton in Hi-Fi (1956) albums during this time are very impressive as a be-bop recording and then a standard dance recording (respectively).[2] Kenton in Hi-Fi's wide popularity and sales benefited from the fact it was his greatest hits of ten years earlier re-recorded in stereo with a contemporary, much higher level band. The album climbed all the way up to #22 on the Billboard album charts and provided much needed revenue at a time when Rock n Roll had started to become the dominant pop music in the United States.[2] It would become more and more difficult for Kenton to alternate between 'dance' and serious 'jazz' albums while staying financially solvent.

During the summer of 1955 (July–September), Kenton was to become the host of the CBS television series Music 55. While it offered 10 weeks of great exposure to a rapidly expanding television audience, the show failed. It was plagued by poor production techniques and a strange combination of guests that did not work well with what Kenton had envisioned. He ended up being stiff and out of place with what the producers tried to achieve.[19] Kenton had to burn the candle at both ends, flying in to do the show and then flying back to meet his band on the road. The New York production team was limited to using an American Federation of Musicians roster of local players; Kenton wanted his own band to do the show. There would be another attempt for the Kenton organization to place the band on regularly scheduled television programming in 1958. After six Kenton-financed episodes on KTTV in Los Angeles, there would be no sponsors to step up and back the show.[2]

One of the standout projects and recordings for the mid-1950s band is the Cuban Fire! album released in 1956. Though Stan Kenton had recorded earlier hits such as The Peanut Vendor in 1947 with Latin percussionist Machito, as well as many other Latin flavored singles, the Cuban Fire! suite and LP stands as a watershed set of compositions for Johnny Richards' career and an outstanding commercial/artistic achievement for the Kenton orchestra, and a singular landmark in large ensemble Latin jazz recordings.[20][2] "CUBAN FIRE is completely authentic, the way it combines big-band jazz with genuine Latin-American rhythms."[21] The success of the Cuban Fire! album can be gauged in part by the immediate ascent of Johnny Richards' star after its release; he was suddenly offered a contract by Bethlehem Records to record what would be the first of several recordings with his own groups.[2]

At one point, Kenton faced a controversy in 1956 with comments he made when the band returned from a European tour. The current Critics Poll in Down Beat was now dominated by African-American musicians in virtually every category. The Kenton band was playing in Ontario, Canada, at the time, and Kenton dispatched a telegram which lamented "a new minority, white jazz musicians", and stated his "disgust [with the so-called] literary geniuses of jazz". Jazz critic Leonard Feather responded in the October 3, 1956, issue of Down Beat with an open letter that questioned Kenton's racial views. Feather implied that Kenton's failure to win the Critics Poll was probably the real reason for the complaint, and wondered if racial prejudice was involved. Less than 2% of the more than 600 sidemen with the Kenton band were African American.[citation needed]

By the end of the decade Kenton was with the last incarnation of a 19-piece, 1950s-style Kenton orchestra. Many bands have been called a leader's "best"; this last Kenton 1959 incarnation of the 1950s bands may very well be the best. The group would pull off one of Kenton's most artistic, subtle and introspective recordings, Standards in Silhouette. As trombonist Archie LeCoque recalled of this album of very slow ballads, "...it was hard, but at the time we were all young and straight-ahead, we got through it and (two) albums came out well."[2] By 1959 Stereophonic sound recording was now being fully utilized with all major labels. One of the great triumphs of the Standards in Silhouette album is the mature writing, the combination of the room used, a live group with very few overdubs, and the recording being in full stereo fidelity (and later remastered to digital).[22] Bill Mathieu was highly skeptical of the decision to record his music like Cuban Fire! in a cavernous ballroom. Mathieu adds: "Stan and producer Lee Gillette were absolutely right: the band sounds alive and awake (which is not easy when recording many hours of slow-tempo music in a studio), and most importantly, the players could hear themselves well in the live room. The end result is the band sounds strong and cohesive, and the album is well recorded."[23] This is the last set of studio dates before Kenton would retool the entire orchestra in 1960.

1960s

[edit]

The Kenton orchestra had been on a slow decline in sales and popularity in the late 1950s with having to compete with newer, popular music artists such as Elvis Presley, Bobby Darin, and The Platters. The nadir of this decline was around 1958 and coincided with a recession that was affecting the entire country.[2] There were far fewer big bands on the road and live music venues were hard to book for the Kenton orchestra. The band would end 1959 beaten up by poor attendance at concerts and having to rely far more on dance halls than real jazz concerts.[23] The band would reform in 1960 with a new look, a new sound, a larger group with a 'mellophonium' section added and an upsurge in Kenton's popularity.[2][23]

The new instrument was used by Kenton to "bridge the gap" in range, color, and tonality between his trumpet and trombone sections. Essentially it creates a conical, midrange sound that is common in a symphonic setting with a horn (French horn) but the bell of the instrument faces forward. Kenton's 1961 recording The Romantic Approach for Capitol is the first of 11 LPs that would feature the "mellophonium band". Kenton arranged the whole first mellophonium album himself and it was very well received in a September 1961 review in Down Beat.[24]

I loved playing Johnny's music, and so did Stan. West Side Story was probably the toughest album I ever recorded...

— Jerry McKenzie[23]

The Kenton Orchestra from 1960 to 1963 had numerous successes; the band had a relentless recording schedule. The albums Kenton's West Side Story (arrangements by Johnny Richards) and Adventures In Jazz, each won Grammy awards in 1962 and 1963 respectively. Ralph Carmichael wrote a superb set of Christmas charts for Kenton which translated into one of the most popular recordings from the band leader to date: A Merry Christmas!. Also, Johnny Richards' Adventures in Time suite (recorded in 1962) was the culmination of all things the mellophonium band was capable of.[2][25] After the Fall 1963 U.S./U.K. tour ended in November, the mellophonium incarnation of Kenton bands was done. The conditions of Stan's divorce from jazz singer Ann Richards was that a judge ordered Stan to take a year off the road to help raise their two children or lose custody altogether.[26] Kenton would not reform another road band for tour until 1965.

Kenton had ties from earlier writing of country/western songs that were a success with Capitol and again he tried his hand in that genre during the early 1960s. In a music market that was becoming increasingly tight, in 1962 he cut the hit single "Mama Sang a Song"; his last Top-40 (No. 32 Billboard, No. 22 Music Vendor). The song was a narration written by country singer Bill Anderson and spoken by Kenton. The single also received a Grammy nomination the following year in the Best Documentary or Spoken Word Recording category. The other attempt he made into that market was the far less successful Stan Kenton! Tex Ritter!, released in 1962 as a full LP.

After the breakup of the mellophonium band, Kenton / Wagner (1964) was an important recording project that Kenton himself arranged, again moving towards "progressive jazz" or third stream music. This album was not a financial success but kept Kenton at the forefront of 'art music' interpretation in the commercial music world. Stan Kenton Conducts the Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra (1965) was an artistic success that garnered another Grammy nomination for the band leader. During this time Kenton also co-wrote the theme music for the short lived NBC television series Mister Roberts (1965–66).

The 1966–1969 Capitol releases for Stan Kenton were a severe low point for his recording career. Capitol producer Lee Gillette was trying to exploit the money making possibilities of numerous popular hits to include the 1968 musical Hair featuring contemporary rock music.[2] Due to lack of promotion by Capitol, four LPs were financial failures; this would be the last releases for Kenton under the aegis of long time Kenton producer Lee Gillette and Capitol.[2] In fact, by the time it was recorded Kenton had no involvement in the Hair LP except for Kenton's name placed on the jacket cover; Ralph Carmichael and Lennie Niehaus were placed in charge of the project. Two exceptions to this late 1960s period are the Billboard charted single the band cut of the Dragnet theme (1967) and another Kenton presents release featuring the music of composer and ex-bandsman Dee Barton: The Jazz Compositions of Dee Barton (1967). The album featuring Barton's music was another unsung artistic success for the Kenton band though widely unseen commercially by the a music listening public.[2]

1970s

[edit]The transition from Capitol to Creative World Records in 1970 was fraught with difficulties during a time when the music business was changing rapidly. As a viable jazz artist who was trying to keep a loyal but dwindling following, Kenton turned to arrangers such as Hank Levy and Bob Curnow to write material that appealed to a younger audience.[2] The first releases for the Creative World label were live concerts and Kenton had the control he wanted over content but lacked substantial resources to engineer, mix, and promote what Capitol underwrote in the past. Kenton would take a big gamble to bypass the current record industry and rely far more on the direct mail lists of jazz fans which the newly formed Creative World label would need to sell records.[27] Kenton also made his print music available to college and high-school stage bands with several publishers. Kenton continued leading and touring with his big band up to his final performance on August 20, 1978, when he disbanded the group due to his failing health.[28]

In June 1973 Bob Curnow had started as the new artists and repertoire manager overseeing the whole operation of the Creative World Records.[29] It was just the year before (in 1972) the Kenton orchestra recorded the National Anthems of the World double LP with 40 arrangements all done by Curnow.[30] As per Curnow himself:

"That was a remarkable and very difficult time for me. I was managing (Stan's) record company with NO experience in business, writing music like mad, living in a new place and culture (Los Angeles was another world), traveling a LOT (out with the band at least 1 week a month) and trying to keep it together at home."

— Bob Curnow (2013)[31]

When Kenton took to the road during the early 1970s (one in London in 1972) and up to his last tour, he took with him seasoned veteran musicians (John Worster, Willie Maiden, Warren Gale, Graham Ellis, and others) teaming them with relatively unknown young artists, and new arrangements (including those by Hank Levy, Bill Holman, Bob Curnow, Willie Maiden, and Ken Hanna) were used. Many alumni associated with Kenton from this era became educators (Mike Vax, John Von Ohlen, Chuck Carter, Lisa Hittle, and Richard Torres), and a few went on to take their musical careers to the next level,[clarification needed] such as Peter Erskine, Douglas Purviance, and Tim Hagans.[citation needed]

Timeline of Stan Kenton Orchestras

[edit]

Legacy

[edit]Kenton was a significant figure on the American musical scene and made an indelible mark on the arranged type of big band jazz. Kenton's music evolved with the times from 1940 through the 1970s. He was at the vanguard of promoting jazz and jazz improvisation through his service as an educator through his Stan Kenton Band Clinics. The "Kenton Style" continues to permeate big bands at the high school and collegiate level, and the framework he designed for the "jazz clinic" is still widely in use today.

Starting in the waning days of the big band era, Kenton found many ways to progress his art form. In his hands the size of the jazz orchestra expanded greatly, at times exceeding forty musicians. The frequency range (high and low notes) was also increased with the use of bass trombones and tuba, and baritone and bass saxophones. The dynamic range was pushed on both ends; the band could play softer and louder than any other big band. Kenton was the primary band leader responsible for moving the big band from the dance hall to the concert hall; one of the most important and successful players in the Third Stream movement.

Interest in his music has experienced somewhat of a resurgence, with critical "rediscovery" of his music and many reissues of his recordings. An alumni band named for him tours, led by lead trumpeter Mike Vax, which performs not only classic Kenton arrangements, but also new music written and performed by the band members (much like Kenton's own groups). Kenton donated his entire library to the music library of North Texas State University[32] (now the University of North Texas), and the Stan Kenton Jazz Recital Hall was named in his honor, although has recently been changed due to concerns over his history of sexual misconduct. His arrangements are now published by Sierra Music Publications.[33]

When compared with the four longest running touring jazz orchestras (Stan Kenton, Woody Herman, Count Basie, and Duke Ellington), Kenton's band had the highest turnover of personnel: Bob Gioga, Buddy Childers, and Dick Shearer are among only the few who played for Kenton for over a decade. Other important soloists such as Lennie Niehaus, Bill Perkins and Chico Alvarez had lengthy stays on the band as well. The full list of notable jazz players, studio musicians, et al. who served a stint is in itself impressive, as is the consistency of the group as a going concern from 1941 right until the decade of Kenton's death in 1979. Kenton's leadership and musical vision marshalled the numerous forces of an evolving and transient diverse set of players and arrangers for nearly four decades.

Personal life

[edit]Kenton's birth certificate stated that he was born on December 15, 1911, according to British biographer Michael Sparke.[21]

Kenton was conceived out of wedlock, and his parents told him that he was born on February 19, 1912, two months later than the actual date, to obscure this fact. Kenton believed well into adulthood that the February date was his birthday, and recorded the Birthday In Britain concert album on February 19, 1973.[34]

The true date remained secret, and his grave marker shows the incorrect February birthdate.[21]

Kenton was married three times. He had three children from the first two marriages. His first marriage was to Violet Rhoda Peters in 1935 and lasted 15 years. The couple had a daughter in 1941, Leslie. In her 2010 memoir Love Affair, Leslie Kenton wrote that, from 1952 to 1954 when she was between the ages of 11 and 13, her father sexually abused her.[35] She nonetheless maintained a close relationship with him, though she states that she was emotionally scarred by the experience.[36][37][38][39] She said that the abuse happened when he was drunk. 20 years later he apologized.[40][36][37]

In 1955, Stan Kenton married San Diego-born singer Ann Richards, who was 23 years his junior. They had two children. In 1961, Richards posed for a nude layout in Playboy magazine's June 1961 issue.[41] She signed a contract to record with Atco Records, without her husband's knowledge.[42] The Playboy shoot was done without Kenton's knowledge; he found out about it while playing at the Aragon Ballroom in Chicago when handed the magazine by Charles Suter, who was the editor of Down Beat magazine at the time.[43] Richards was not typically on the road with the band, though she had recorded the album Two Much! with Kenton in 1960. Richards filed for divorce in August 1961;[44] it was finalized in 1962. He retained custody of their two children.[45][2]

Kenton's third marriage was to KABC production assistant Jo Ann Hill, in 1967. This also ended in a separation in 1969 with the divorce following in 1970.[2]

In his later years he lived with his public relations secretary and last business manager, Audree Coke Kenton, though they never married.[citation needed]

Kenton's heavy consumption of alcohol contributed to frequent accidents and the physical difficulties he encountered during the last 10 years of his life.[46][40]

Kenton's son Lance became a member of the controversial Synanon new-age community in California, and served as one of its "Imperial Marines", a group entrusted with committing violence against former members and others considered enemies of the community. In 1978 he was arrested for helping to put a rattlesnake in the mailbox of an anti-Synanon lawyer, and was sentenced to a year in prison.[47][48]

Kenton had two serious falls, one in the early 1970s and one in May 1977 whilst on tour in Reading, Pennsylvania,[49] the second of which fractured his skull. On August 17, 1979, he was admitted to Midway Hospital near his home in Los Angeles after a stroke; he died eight days later, on August 25. Kenton was interred in the Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery, Los Angeles.[47][3]

Gold records and charts (singles and albums)

[edit]Gold Records

- 1944 Artistry in Rhythm (Capitol Records) instrumental

- 1945 Tampico (Capitol Records) vocal by June Christy and band

- 1945 Shoo-Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy (Capitol Records) vocal by June Christy and band

Hits as charted singles

[edit](Songs that reached the top of the US or UK charts)

Between 1944 and 1967, Stan Kenton had numerous hits on Billboard's charts.[50]

| year | Title | Chart peak position | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | Year end position | US R&B |

US Country |

US Adult Contemporary | ||

| 1944 | Do Nothin' Till You Hear from Me (sung by Red Doris) | 20 | 8 | |||

| 1944 | Eager Beaver | 14 | ||||

| 1944 | And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine (sung by Anita O'Day) | 4 | 27 | |||

| 1944 | How Many Hearts Have You Broken (sung by Gene Howard) | 9 | ||||

| 1945 | Tampico (sung by June Christy) | 2 | 46 | |||

| 1945 | It's Been a Long, Long Time (sung by June Christy) | 6 | ||||

| 1946 | Artistry Jumps | 13 | ||||

| 1946 | Just A-Sittin' and A-Rockin' (sung by June Christy) | 16 | ||||

| 1946 | Shoo-Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy (sung by June Christy) | 6 | ||||

| 1946 | It's a Pity to Say Goodnight (sung by June Christy) | 12 | ||||

| 1947 | His Feet Too Big for De Bed (sung by June Christy) | 12 | ||||

| 1947 | Across the Alley from the Alamo (sung by June Christy) | 11 | ||||

| 1948 | How High the Moon (sung by June Christy) | 27 | 27 | |||

| 1950 | Orange Colored Sky (sung by Nat King Cole) | 5 | ||||

| 1951 | September Song | 17 | ||||

| 1951 | Laura | 12 | ||||

| 1952 | Delicado | 25 | ||||

| 1960 | My Love (sung by Nat King Cole) | 47 | 12 | |||

| 1962 | Mama Sang a Song (spoken word by Stan Kenton) | 32 | 12 | |||

| 1967 | Dragnet | 40 | ||||

Hits as charted albums

[edit](Albums charting history with Billboard Magazine)

| year | Album | Chart peak/ year end # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak, US | Year end | |||||

| 1946 | Artistry in Rhythm | 2 (1/11/47) | #15 (1947) | |||

| 1948 | A Presentation of Progressive Jazz | *1 (5/29 – 7/17) | #1 | |||

| 1949 | Encores | 2 (2/26/49) | ||||

| 1950 | Innovations in Modern Music | 4 (4/22/50) | ||||

| 1956 | Kenton in Hi-Fi | 20 (5/5/56) | #22 | |||

| 1956 | Cuban Fire! | 17 (9/15/56) | ||||

| 1961 | West Side Story | 16 (Oct. 1961) |

||||

| 1972 | Stan Kenton Today | 146 (7/8/72) | ||||

Awards and honors

[edit]Wins and honors from major publications

[edit]| Year | Music publication |

won | honor named |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1946 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| Down Beat | Best band of 1946 | ||

| 1947 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| Metronome All-Stars | |||

| Down Beat | Best band of 1947 | ||

| 1948 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| 1950 | Down Beat | Best band of 1950 | |

| 1951 | Best band of 1951 | ||

| 1952 | Best band of 1952 | ||

| 1953 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| Down Beat | Best band of 1953 | ||

| 1954 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| Down Beat | Best band of 1954 | ||

| Hall of Fame | |||

| 1955 | Metronome | Band of the year | |

| 1957 | Playboy | Jazz Artist of the Year | |

| 1958 | |||

| 1959 | |||

| 1960 |

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | West Side Story (album) | Best Performance by an orchestra - for other than dancing | Nominated |

| Best Jazz Performance - Large Group (Instrumental) | Won | ||

| 1963 | Adventures In Jazz (album) | Won | |

| Best Engineered recording (other than classical and novelty) | Nominated | ||

| 1963 | Mama Sang a Song (single) | Best Documentary or Spoken Word Recording (other than comedy) | Nominated |

| 1965 | Artistry in Voices and Brass (album) | Best Performance by a Chorus | Nominated |

| 1967 | Stan Kenton Conducts the Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra (album) | Best Instrumental Jazz Performance, Individual or Group | Nominated |

Grammy Hall of Fame

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1943 | Artistry in Rhythm (with the Stan Kenton Orchestra) | Grammy Hall of Fame (1985) | Inducted |

International Music Awards

[edit]| Year | Award | Country | Album or single | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Edison Award | Netherlands | The World We Know (album) | Capitol |

Other awards and honors

[edit]- 1978 – Honorary Doctorate of Music: University of Redlands

- 1974 – Honorary Doctorate of Humane Letters: Drury College

- 1968 – Honorary Doctorate of Music: Villanova University

- 1967 – Intercollegiate Music Festival Hall of Fame Award

- Named to the International Association for Jazz Education Hall of Fame (1980)

- Honored on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (Recording – 6340 Hollywood Blvd.)

- "City of Glass" is honored in The Wire's "100 Records That Set The World on Fire" (While No One Was Listening)".

Posthumously honored

[edit]- 2011 – Stan Kenton: Artistry In Rhythm- Portrait Of A Jazz Legend (DVD)

EMPixx Awards – Platinum Award in the Documentary Category/Platinum Award in the Use of Music Category.

United States Library of Congress National Recording Registry

- Artistry in Rhythm (single) – Stan Kenton – Released:1943 – Inducted: 2011 - Category: Jazz

Noted band personnel

[edit]- Instrumentalists

- Pepper Adams

- Bob Ahern

- Sam Aleccia

- Ashley Alexander

- Laurindo Almeida

- Alfred "Chico" Alvarez

- Jim Amlotte

- John Anderson

- Buddy Arnold

- Don Bagley

- Gabe Baltazar

- Michael Bard

- Dave Barduhn

- Gary Barone

- Dee Barton

- Tim Bell

- Max Bennett

- Milt Bernhart

- Bill Briggs

- Bud Brisbois

- Ray Brown

- Bob Burgess

- Bart Caldarell

- Tony Campise

- Frank Capp

- Conte Candoli

- Pete Candoli

- Fred Carter

- Billy Catalano

- Bill Chase

- Buddy Childers

- Rich Condit

- Bob Cooper

- Jack Costanzo

- Curtis Counce

- Bob Curnow

- Quinn Davis

- Vinnie Dean

- Jay Daversa

- Ted Dechter (Trombone) [52][53][54]

- Don Dennis

- Sam Donahue

- Red Dorris

- Peter Erskine

- Don Fagerquist

- Maynard Ferguson

- Mary Fettig

- Bob Fitzpatrick

- Dr. William "Bill" Fritz

- Carl Fontana

- Chris Galuman

- Stan Getz

- Bob Gioga

- John Graas

- Benny Green[55]

- Tim Hagans

- Ken Hanna

- Bill Hanna

- John Harner

- Dennis Hayslett

- Gary Henson

- Phil Herring

- Skeets Herfurt

- Lisa Hittle

- Gary Hobbs

- Bill Holman

- Marvin "Doc" Holladay

- Clay Jenkins

- Richie Kamuca

- Melvin Kannel

- Joel Kaye

- Red Kelly

- Jimmy Knepper

- Bobby Knight

- Lee Konitz

- Tom Lacy

- Scott LaFaro

- Jack Lake

- Keith LaMotte

- Kent Larsen

- Terry Layne

- Skip Layton

- Gary Lefebvre

- Archie LeCoque

- Stan Levey

- Mel Lewis

- Ramon Lopez

- Bob Lymperis

- John Madrid

- Willie Maiden

- Shelly Manne

- Charlie Mariano

- Al Mattaliano

- Dave Matthews

- Jerry McKenzie

- Dick Meldonian

- Don Menza

- Greg Metcalf

- Eddie Meyers

- Frank Minear

- Vido Musso

- Boots Mussulli

- Lennie Niehaus

- Dennis Noday

- Sam Noto

- Lloyd Otto

- Don Paladino

- John Park

- Kim Park

- Art Pepper

- Bill Perkins

- Oscar Pettiford

- Al Porcino

- Mike Price

- Douglas Purviance

- Ray Reed

- Clyde Reasinger

- Roy Reynolds

- Kim Richmond

- George Roberts

- Gene Roland

- Billy Root

- Frank Rosolino

- Shorty Rogers

- Ernie Royal

- Howard Rumsey

- Bill Russo

- Eddie Safranski

- Sal Salvador

- Carl Saunders

- Jay Saunders

- Dave Schildkraut

- Paul Severson

- Bud Shank

- Dick Shearer

- Jack Sheldon

- Kenny Shroyer

- Gene Siegel

- Zoot Sims

- Tom Slaney

- Dalton Smith

- Greg Smith

- Mike Snustead

- Ed Soph

- Lloyd Spoon

- Mike Suter

- Marvin Stamm

- Ray Starling

- Vinnie Tano

- Lucky Thompson

- Richard Torres

- Bill Trujillo

- Jeff Uusitalo

- Mike Vaccaro

- David van Kriedt

- Bart Varsalona

- Mike Vax

- John Von Ohlen

- George Weidler

- Ray Wetzel

- Rick Weathersby

- Jiggs Whigham

- Stu Williamson

- Kai Winding

- John Worster

- Alan Yankee

- Composers and Arrangers

- Manny Albam

- Buddy Baker

- Dave Barduhn

- Dee Barton

- Ralph Carmichael

- Joe Coccia

- Frank Comstock

- Bob Curnow

- Dale Devoe

- Sam Donahue

- Wayne Dunston

- Dennis Farnon

- Bob Florence

- Bill Fritz

- Bob Graettinger

- Ken Hanna

- Neal Hefti

- Bill Holman

- Gene Howard

- Hank Levy

- Willie Maiden

- Franklyn Marks

- Bill Mathieu

- Gerry Mulligan

- Lennie Niehaus

- Boots Mussulli

- Chico O'Farrill

- Marty Paich

- Johnny Richards

- Shorty Rogers

- Gene Roland

- Pete Rugolo

- Bill Russo

- Paul Severson

- Charlie Shirley

- Steve Spiegl

- Ray Starling

- Mark Taylor

- Al Yankee

- Ralph Yaw

- Vocalists

- Ernie Bernhardt

- Cindy Bradley

- Kay Brown

- Helen Carr

- June Christy

- Chris Connor

- Red Dorris

- Kay Gregory

- Gene Howard

- Jay Johnson

- Eve Knight

- Kent Larsen

- Dolly Mitchell

- The Modern Men

- Anita O'Day

- The Pastels

- Ann Richards

- Frank Rosolino

- Gail Sherwood

- Jan Tober

- Jean Turner

- Jerri Winters

- Ray Wetzel

Discography and on film and television

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Stan Kenton and His Orchestra – McGregor No. LP201 (1941)

- The Formative Years – Decca No. 589 489-2 (1941–1942)

- Artistry in Rhythm – Capitol No. BD39 (1946)

- Encores – Capitol No. 155 (1947)

- A Presentation of Progressive Jazz – Capitol No. T172 (1947)

- Metronome Riff (single) – Capitol special pressing (1947)

- Innovations in Modern Music – Capitol No. 189 (1950)

- Stan Kenton's Milestones – Capitol No. T190 (through 1950)

- Stan Kenton Presents – Capitol No. 248 (1950)

- City of Glass – Capitol No. H353 (1951)

- New Concepts of Artistry in Rhythm – Capitol 383 (1952)

- Popular Favorites by Stan Kenton – Capitol No. 421 (1953)

- Sketches on Standards – Capitol No. 426 (1953)

- This Modern World – Capitol No. 460 (1953)

- Portraits on Standards – Capitol No. 462 (1953)

- Kenton Showcase: The Music of Bill Russo – Capitol No. H525 (1954)

- Kenton Showcase : The Music of Bill Holman – Capitol No. H526 (1954)

- Duet (with June Christy) – Capitol No. 656 (1955)

- Contemporary Concepts – Capitol No. 666 (1955)

- Kenton in Hi-Fi – Capitol No. 724 (1956)

- Cuban Fire! – Capitol No. 731 (1956)

- Kenton with Voices – Capitol No. 810 (1957)

- Rendezvous with Kenton – Capitol No. 932 (1957)

- Back to Balboa – Capitol No. 995 (1958)

- The Ballad Style of Stan Kenton – Capitol No. 1068 (1958)

- Lush Interlude – Capitol No. 1130 (1958)

- The Stage Door Swings – Capitol No. 1166 (1958)

- The Kenton Touch – Capitol No. 1276 (1958)

- Viva Kenton! – Capitol No. 1305 (1959)

- Standards in Silhouette – Capitol No. 1394 (1959)

- Two Much! (with Ann Richards) – Capitol No. 1495 (1960)

- The Romantic Approach – Capitol No. 1533 (1961)

- Kenton's West Side Story – Capitol No. 1609 (1961)

- A Merry Christmas! – Capitol No. 1621 (1961)

- Sophisticated Approach – Capitol No. 1674 (1961)

- Adventures in Standards – Creative World No. 1025 (1961 – released 1975)

- Adventures In Jazz – Capitol No. 1796 (1961)

- Adventures in Blues – Capitol No. 1985 (1961)

- Stan Kenton! Tex Ritter! (with Tex Ritter) – Capitol No. 1757 (1962)

- Adventures in Time – Capitol No. 1844 (1962)

- Artistry in Bossa Nova – Capitol No. 1931 (1963)

- Artistry in Voices and Brass – Capitol No. 2132 (1963)

- Stan Kenton / Jean Turner (with Jean Turner) – Capitol No. 2051 (1963)

- Kenton / Wagner – Capitol No. 2217 (1964)

- Stan Kenton Conducts the Los Angeles Neophonic Orchestra – Capitol No. 2424 (1965–1966)

- Stan Kenton Plays for Today – Capitol No. 2655 (1966–1967)

- The World We Know – Capitol No. 2810

- The Jazz Compositions of Dee Barton – Capitol No. 2932 (1967)

- Finian's Rainbow – Capitol No. 2971 (1968)

- Hair – Capitol No. ST305 (1969)

- National Anthems of the World – Creative World No. 1060 (1972)

- 7.5 on the Richter Scale – Creative World No. 1070 (1973)

- Stan Kenton Without His Orchestra (solo) – Creative World No. 1071 (1973)

- Stan Kenton Plays Chicago – Creative World No. 1072 (1974)

- Fire, Fury and Fun – Creative World No. 1073 (1974)

- Kenton '76 – Creative World No. 1076 (1976)

- Journey Into Capricorn – Creative World No. 1077 (1976)

Live albums

[edit]- Stan Kenton Live at Cornell University (1951)

- Stan Kenton Stompin' at Newport – Pablo #PACD-5312-2 (1957)

- On the Road with Stan Kenton – Artistry Records #AR-101 (Recorded November 6, 1958, at the Municipal Auditorium, Sarasota, Florida)

- Kenton Live from the Las Vegas Tropicana – Capitol No. 1460 (1959)

- Road Show (with June Christy and The Four Freshmen) – Capitol #TBO1327 (1959)

- Stan Kenton at Ukiah – Status #STCD109 (1959)

- Stan Kenton in New Jersey – Status #USCD104 (1959)

- Mellophonium Magic – Status No. CD103 (1962)

- Mellophonium Moods – Status No. STCD106 (1962)

- Stan Kenton and His Orchestra at Fountain Street Church Part 1 – Status #DSTS1014 (1968)

- Stan Kenton and His Orchestra at Fountain Street Church Part 2– Status #DSTS1016 (1968)

- Private Party – Creative World No. 1014 (1970)

- Live At Redlands University – Creative World No. 1015 (1970)

- Live at Brigham Young University – Creative World No. 1039 (1971)

- Live at Butler University – Creative World No. 1058 (1972)

- The Stuttgart Experience – Live In Stuttgart – Jazzhaus #JAH-457 (1972)

- Stan Kenton Today – Live In London – London/Creative World #BP 44179-80 (1972)

- Birthday in Britain – Creative World #ST 1065 (1973)[34]

- Flying High in Florida (1972)

- Live at the London Hilton – Part I & II (1973)

- Live in Europe (1976)

- The Lost Concert Vol. 1–2 Recorded at The Cocoanut Grove in Los Angeles, CA on March 18, 1978, posthumous release in 2002 – Jazz Heritage

Compilations

[edit]- Stan Kenton's Milestones (Capitol, 1943–47 [1950])

- Stan Kenton Classics (Capitol, 1944–47 [1952])

- The Kenton Era (Capitol, 1940–53 [1955])

- City of Glass and This Modern World – Capitol No. 736 (1951–1953 [1957])

- Stan Kenton's Greatest Hits (Capitol, 1943–47 [1965])

- Stan Kenton On AFRS – Status DSTS1019 (1944–1945)

- One Night Stand – Magic #DAWE66 (1961–1962)

- Some Women I've Known – Creative World No. 1029

- The Fabulous Alumni of Stan Kenton – Capitol No. T 20244 (1970)

- The Complete Capitol Recordings Of The Holman And Russo Charts – Mosaic MD4-136

- The Complete Capitol Recordings – Mosaic MD7-163

- The Peanut Vendor

- The Jazz Compositions Of Stan Kenton – Creative World No. ST1078 (1945–1973)

- Street of Dreams – Creative World No. 1079 (1979 vinyl; 1992 CD)

- The Innovations Orchestra (Capitol, 1950–51 [1997])

On film or television

[edit]- 1941 Zig Me, Baby, With a Gentle Zag (short)

- 1942 Jammin' in the Panoram (short)

- 1942 Jealous (short)

- 1942 Reed Rapture (short)

- 1944 This Love of Mine (short)

- 1945 Eager Beaver (short)

- 1945 I'm Homesick, That's All (short)

- 1945 It's Been a Long Long Time (short)

- 1945 Southern Scandal (short)

- 1945 Tampico (short)

- 1946 Talk About A Lady (feature film)[56]

- 1946 Southern Scandal (short)

- 1947 Let's Make Rhythm (short)

- 1947 Stan Kenton and His Orchestra (biographical short)

- 1950 The Ed Sullivan Show (television)[57]

- 1953 Schlagerparade (movie) Stan Kenton at the Sporthalle in Berlin

- 1954 Spotlight No. 5 (CBC television, documentary)

- 1955 Music '55 (television, musical variety)[19]

- 1956 Happy New Year: A Sunday Spectacular (television)

- 1956 Juke Box Jury (television, gameshow)

- 1957 Alan Melville Takes You from A-Z (BBC television)

- 1957 The Big Record (television)

- 1958 The Gisele MacKenzie Show (television)

- 1960 General Electric Theater (television)

- 1960 Startime (television)

- 1960 Dixieland Small-Fry (television)

- 1962 Jazz Scene USA (television)

- 1962 Music of the 60s (television)

- 1962 The Lively Ones (television)

- 1963 The Ed Sullivan Show (television)

- 1964 The Les Crane Show (television)

- 1965 Big Bands (WGN-TV television)

- 1965 Jamboree (television)

- 1966 The Linkletter Show (television)

- 1967 The Woody Woodbury Show (television)

- 1967 The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (television)

- 1968 Something Special with Mel Torme (television)

- 1968 The Crusade for Jazz aka Bound To Be Heard (television documentary)

- 1969 The Substance of Jazz (educational/documentary)

- 1969 and 1970 The David Frost Show (television)

- 1968 and 1970 The Mike Douglas Show (television)

- 1971 The Merv Griffin Show (television)

- 1972 Sounds of Saturday (BBC television)

- 1976 Soundstage (television)

- 1977 Omnibus (BBC television)

- 2011 Stan Kenton: Artistry In Rhythm- Portrait Of A Jazz Legend (documentary)

Compositions

[edit]Stan Kenton's compositions include "Artistry in Rhythm", released as V-Disc No. 285B, "Opus in Pastels", "Artistry Jumps", "Reed Rapture", "Eager Beaver", released on V-Disc 285B, "Fantasy", "Southern Scandal", which was released as V-Disc No. 573B, "Monotony", released as V-Disc No. 854B, in 1948, with a spoken introduction by Kenton, "Harlem Folk Dance", "Painted Rhythm", "Concerto to End All Concertos", "Easy Go", "Concerto for Doghouse", "Shelly Manne", "Balboa Bash", "Flamenco", and "Sunset Tower".[58]

Many compositions are collaborations between Stan Kenton and Pete Rugolo, such as "Artistry in Boogie", "Collaboration", and "Theme to the West". Kenton was credited as a co-writer of the 1944 jazz classic "And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine".

Kenton and Drum Corps

[edit]Many of the Kenton band's arrangements have been popular with drum corps, where the contrasting dynamics and demanding brass playing are particularly suited to the competitive nature of the activity.[59] Of particular note are Madison Scouts championship-winning performance of Malaguena in 1988, Suncoast Sound's 1986 repertoire based on Adventures in Time, and Blue Devils Drum and Bugle Corps 1992 suite from Cuban Fire.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Christgau, Robert (November 25, 1971). "When You Consider Your Condition . . ". The Village Voice. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Sparke, Michael. Stan Kenton: This is an Orchestra. UNT Press (2010). ISBN 978-1-57441-325-0.

- ^ a b c Jones, Jack. "Stan Kenton, Innovative Band Leader, Dies At 67". Los Angeles Times. August 26, 1979. pp. 1

- ^ a b Scott Yanow. "Stan Kenton | Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 9, 2013. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ Spelvin, George (February 21, 1942). "Broadway Beat" (PDF). Billboard. p. 5. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "Joseph Greene, Composer With Stan Kenton's Orchestra, Dies". Los Angeles Times. June 28, 1986. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 13, 2015.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – Pete Rugolo and Progressive Jazz". All Things Kenton. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Sparke, Michael (2010). "7. The Artistry Orchestra (1946)". Stan Kenton: this is an orchestra!. Denton, Tex.: University of North Texas Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-57441-284-0. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – Progressive Jazz Essay". allthingskenton.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – A Presentation of Progressive Jazz". allthingskenton.com. Archived from the original on December 15, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Herrick, Tom. "Record Review. A Presentation of Progressive Jazz." Down Beat 15, no. 11 (June 2, 1948): 14.

- ^ Simon, George T., and Barry Ulanov. "Record Review. A Presentation of Progressive Jazz." Metronome 64, no. 6 (1948-06): 36.

- ^ "Record Review. A Presentation of Progressive Jazz." Billboard 60, no. 21 (May 22, 1948): 41.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – Progressive Jazz Personnel". allthingskenton.com. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ Barry Ulanov in Metronome magazine, 1948, cited at Wilson, John S. (August 27, 1979). "Stan Kenton, Band Leader, Dies; Was Center of Jazz Controversies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – Progressive Jazz Down Beat Poll Winners". allthingskenton.com. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "15,000 Pack Bowl to Dig Kenton Bash." Down Beat 15, no. 15 (July 28, 1948): 1.

- ^ a b Rout Jr, Leslie B. "Economics and Race in Jazz", in Ray Broadus Browne (ed.), Frontiers of American Culture, 1968, 154-171.

- ^ a b "Stan Kenton Music '55". All Things Kenton.

- ^ Lawn, Richard (2007). "Experiencing Jazz". McGraw-Hill, p. 442. ISBN 978-0-07-245179-5.

- ^ a b c Sparke, Michael (2011). Stan Kenton: This Is an Orchestra!. North Texas Lives of Musicians. Denton, Texas: University of North Texas Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1574413250. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ author of this page: 'I have over 1000 classical and jazz CDs and "Standards..." is a shining star. I have heard very few recordings that are so enjoyable to listen to in terms of overall quality of sound, especially now on digital CD.'

- ^ a b c d Sparke, Michael; Peter Venudor (1998). Stan Kenton, The Studio Sessions. Balboa Books. ISBN 0-936653-82-5.

- ^ Tynan, John. review of The Romantic Approach, September 28, 1961, Down Beat magazine.

- ^ NPR: Stan Kenton At 100: Artistry In Rhythm Archived October 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Reference to Adventures in Time in article as important milestone of Kenton's music. February 17, 2012.

- ^ Lee, William. "Stan Kenton: Artistry in Rhythm". Creative Press, Los Angeles. 1980.

- ^ Lee, William F. (1980), "Stan Kenton: Artistry in Rhythm, Los Angeles: Creative Press, Los Angeles, p. 365. ISBN 089745-993-8

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 31 Aug 1978, page 99". Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Lee, William F. (1980) "Stan Kenton: Artistry in Rhythm". Creative Press, Los Angeles. pp. 374 ISBN 089745-993-8

- ^ Easton, Carol (1973), "Straight Ahead: The Story of Stan Kenton". William Morrow & Co. Inc., New York, p. 247 ISBN 0-688-00196-3.

- ^ Dr. Jack Cooper, Assoc. Professor. of Music, University of Memphis (February 16, 2013). "Email interview with Bob Curnow" (Interview).

{{cite interview}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "University of North Texas Libraries". Library.unt.edu. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ "Stan Kenton Orchestra". Sierramusicstore.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2013. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ a b "Stan Kenton And His Orchestra – Birthday In Britain". Discogs. 1973. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2014. The album was recorded on February 19, which is not Kenton's birthday; at the time, he either thought it was, or was publicly maintaining that it was.

- ^ Kenton, Leslie (2010). Love Affair. Vermilion (Ebury Publishing). ISBN 978-0312659080.

- ^ a b Boleman-Herring, Elizabeth (February 18, 2012). "Stan Kenton & His Daughter Leslie's 'Love Affair'". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Duerden, Nick (February 19, 2010). "Leslie Kenton: 'I was angry, but never hated my father'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2016.

- ^ Wolff, Carlo (February 20, 2011). "Stan Kenton's daughter opens door to their dark past". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ Will Friedwald (January 28, 2011). "A Restless Soul Revealed". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ^ a b Singh, Anita (January 30, 2010). "Jazz great Stan Kenton raped his daughter, she claims in new book". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ Playboy Magazine, June 1961, Ann Richards photo layout Archived November 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The LP cover photo of Ann Richards for the Atco Records release was a picture taken from the Playboy photo shoot, but edited.

- ^ Harris, Steven. The Kenton Kronicles. Dynaflow Publications. 2000. ISBN 0-9676273-0-3.

- ^ "Singer Sues Stan Kenton For Divorce". Los Angeles Mirror. August 19, 1961. Retrieved December 11, 2023.

- ^ Gavin, James (September 20, 2017). "Ann Richards: Dreams Have a Way of Fading". Jazz Times. Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 20 Feb 1958, page 1". Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ a b Wilson, John S. (August 27, 1979). "Stan Kenton, Band Leader, Dies; Was Center of Jazz Controversies". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 12 Oct 1978, page 7". Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ "The Los Angeles Times 25 May 1977, page 15". Newspapers.com. Retrieved March 11, 2023.

- ^ Source: charts and data provided by Music VK and Billboard Magazine.

- ^ National Academy of Recordings Arts and Sciences reference page for Stan Kenton - Grammys and nominations Archived April 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ted Dechter Songs, Albums, Reviews, Bio & More". AllMusic.

- ^ "Stan Kenton - Live At Palo Alto". Retrieved March 11, 2023 – via music.metason.net.

- ^ "Stan Kenton: Stan Kenton: Road Shows album review @ All About Jazz". October 28, 2013.

- ^ Morgan, Alun (June 24, 1998). "Obituary: Benny Green". The Independent. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – Talk About A Lady". All Things Kenton. Archived from the original on December 6, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "Maynard Ferguson with Stan Kenton on The Ed Sullivan Show-December 3, 1950-improved quality". Youtube.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ^ "All Things Kenton – The Arrangers – Stan Kenton". All Things Kenton. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2018.

- ^ "Drum Corps Play Kenton". Dci.org.

References

[edit]- Agostinelli, Anthony Joseph (1986). Stan Kenton: The Many Musical Moods of His Orchestras. AJ Agostinelli.

- Colt, Freddy (2013). Stan Kenton, il Vate del Progressive Jazz. Mellophonium Broadsides, San Remo (Italy).

- Easton, Carol (1981). Straight Ahead: The Story of Stan Kenton. Da Capo. ISBN 978-0-306-80152-5.

- Gabel, Edward F. (1993). Stan Kenton: The Early Years, 1941-1947. Lake Geneva, WI: Balboa Books. ISBN 978-0936653518.

- Harris, Steven D. (2003). The Kenton Kronicles: A Biography of Modern America's Man of Music, Stan Kenton. Pasadena: Dynaflow. ISBN 978-0967627304.

- Lee, William F. (1994). Stan Kenton: Artistry in Rhythm. Los Angeles: Creative Press. ISBN 978-0-89745-993-8.

- Sparke, Michael (2011). Stan Kenton: This Is an Orchestra!. North Texas Lives of Musicians Series. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-57441-325-0.

External links

[edit]- Stan Kenton Research Center

- The Stan Kenton Collection at the University of North Texas

- Bell High School Alumni Page for Stan Kenton

- Article on Stan Kenton's Mellophonium Band

- An Interview with Jo Lea Starling, wife of Ray Starling

- An Interview with Tony Scodwell, Stan Kenton Mellophoniumist

- Terry Vosbein's All Things Kenton site - discography, radio shows, rare images and audio.

- An interview with Stan Kenton, Desert Island Discs (UK), April 9, 1956

- 1911 births

- 1979 deaths

- Age controversies

- Cool jazz musicians

- Swing bandleaders

- Big band bandleaders

- Jazz arrangers

- Progressive big band bandleaders

- American jazz bandleaders

- Musicians from California

- American music arrangers

- Grammy Award winners

- Capitol Records artists

- American jazz educators

- Burials at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery

- 20th-century American musicians

- Summit Records artists

- Bell High School (California) alumni

- DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members