Illinois Terminal Railroad

1913-1985 Champaign, Illinois headquarters of the ITS, the ITR and then Illinois Power and Light | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | St. Louis, Missouri |

| Reporting mark | ITC |

| Locale | Central Illinois and St. Louis, Missouri |

| Dates of operation | 1896–1982 |

| Successor | Norfolk and Western Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Overhead line, 3,300 V AC (1907–c. 1910) 650 V DC (c. 1910–1958) |

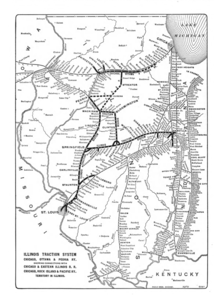

The Illinois Terminal Railroad Company (reporting mark ITC), known as the Illinois Traction System until 1937, was a heavy duty interurban electric railroad with extensive passenger and freight business in central and southern Illinois from 1896 to 1956. When Depression era Illinois Traction was in financial distress and had to reorganize, the Illinois Terminal name was adopted to reflect the line's primary money making role as a freight interchange link to major steam railroads at its terminal ends, Peoria, Danville, and St. Louis. Interurban passenger service slowly was reduced, ending in 1956. Freight operation continued but was hobbled by tight street running in some towns requiring very sharp radius turns. In 1956, ITC was absorbed by a consortium of connecting railroads.

History

[edit]ITC was a successor in interest to a series of interurban railroads that were consolidated in the early 1900s by businessman William B. McKinley into the Illinois Traction System (ITS), an affiliate of the Illinois Power and Light Company. The Illinois Traction System, at its height, provided electric passenger rail service to 550 miles (900 km) of tracks in central and southern Illinois.[1] The system's Y-shaped main line stretched from St. Louis to Springfield, Illinois, with branches onward from Springfield northwest to Peoria and eastward to Danville. A series of affiliated street-level city trolley lines provided local passenger service in many of the cities served by the main line. The longest-lived segment was at East St. Louis area of the line descended from an Edwardsville-Alton interurban line bought by the Illinois Traction System in 1928. Because the Illinois Traction/Illinois Terminal traversed some towns on street trackage with very tight turns, freight operation required the use of short trains and special hardware. New bypass trackage was constructed around some towns for freight operation to partially solve this problem. Springfield was an example of this. In a few other towns, arrangements were made with a parallel steam railroad for trackage rights in order to provide a bypass. An example of difficult town running (for the town as well as the railroad) was at Morton, Illinois, just east of Peoria, where a heavy duty well maintained track with trolley catenary suddenly found itself running down the center of the town's brick paved main street. The system initially utilized electrification at 3,300-volt single phase alternating current between 1907 and about 1910 when it was re-electrified to 650-volt direct current.[2]

Interurban Routes

[edit]- 1 Danville-Ridge Farm (1901-1936)

- 2 Danville-Catlin (1902-1939)

- 3 Homer Branch (1904-1929)

- 4 Danville-Champaign (1902-1953)

- 5 Champaign-Decatur (1907-1955)

- 6 Decatur-Springfield (1904-1955)

- 7 Decatur-Bloomington (1905-1953)

- 8 Bloomington-Peoria (1907-1953)

- 9 Peoria-Springfield (1906-1956)

- 10 Springfield-Granite City (1904-1956)

- 11 Granite City-St. Louis (1910-1958)

- 12 Staunton-Hillsboro (1905-1935)

Decline

[edit]With the Great Depression, the Illinois Traction System staggered. The ITS relinquished many of its city streetcar lines in the 1930s, and due to the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 it was forced to cut its ties with an affiliated firm that provided electrical utility services. The passenger railroad reorganized in 1937 as the Illinois Terminal Railroad (ITR) and continued to provide electric-powered interurban, long-distance multiple car passenger train service Peoria/Danville to St. Louis for almost another two decades. United States postal contracts helped provide revenue to make this service viable.

In the 1950s, with the rise of the automobile, ITC's passenger service became hopelessly unprofitable. This was even after IT had purchased three expensive electric multiple car streamlined train sets ("Streamliners") from St. Louis Car Company. These were capable of decent speeds on ITC's well-maintained open country roadbed, but had to negotiate tight streetcar-style curves in the numerous towns along the line; moreover, they suffered an abnormal number of failures. Worst of all, this new equipment generally failed to attract passengers, even on the St. Louis-Peoria runs which had no railroad or direct highway competition, despite having parlor-observation and dining facilities.[3] On March 3, 1956, ITC's interurban passenger service ended, followed by its last passenger service, the St. Louis-Granite City suburban cars, in 1958.

Because the ITR had some valuable trackage and lineside freight customers, it was acquired in June 1956 by nine Class I railroads. These collectively continued to operate ITR as a diesel-powered short line to carry freight to the acquiring railroads. The co-owned reorganized Illinois Terminal Railroad took down its trolley wire and abandoned much of its trackage, particularly the interurban street running in towns and villages. At various points ITC track was connected to trackage of adjacent lines and was available for optional routing. For the following 25 years (1956-1981) the ITC continued to operate diesel-powered trackage north and east of St. Louis, providing freight business for the railroads that owned it. The Norfolk and Western Railway purchased its partners' interests in the Illinois Terminal Railroad on September 1, 1981, and ITC officially merged into the N&W on May 8, 1982.[4]

Modern operations in St. Louis, Missouri

[edit]In 1989, IT's successor Norfolk Southern sold IT's remaining active trackage in St. Louis, Missouri from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch building at 900 North Tucker Boulevard to the Branch Street Yard located immediately to the south of the McKinley Bridge to Ironhorse Resources, Inc., of O'Fallon, IL. Ironhorse formed a subsidiary for its St. Louis operation known as the Railroad Switching Service of Missouri (RSM). RSM existed to provide freight service to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which received boxcars loaded with newsprint spools that were delivered to an underground freight dock in the basement of its St. Louis headquarters building.[5] The spools were used by the Post-Dispatch in the production of its daily circulation newspaper. The Post-Dispatch from the 1960s to the 1980s operated in a profit sharing arrangement with their competitor the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, and eventually took on the printing of the latter's paper at their location. The Globe-Democrat had occupied the former Midwest Terminal Building (still extant and now known as the Globe Building) headquarters of ITR starting in the 1950s.

RSM's locomotive was an EMD SW-8, formerly owned by the United States Army.[6] When not in use, the locomotive was parked in a fenced-in area in a subway tunnel beneath Tucker Boulevard. Heading north from the Post-Dispatch, the line continued in the subway for approximately four blocks and then ran for another three blocks through the center of Hadley Street. At the Interstate 70 overpass, the trackage meandered through North St. Louis via a 1.5 mile-long trestle to Branch Street where a small interchange yard with Norfolk Southern Railroad was located. RSM's operation of the St. Louis trackage continued until June 21, 2004, when an RSM crew pulled the last empty boxcar from the Post, which had elected to cease using rail service.[5] Following this, RSM's parent company, Ironhorse Resources, applied for, and was subsequently granted, permission from the United States Surface Transportation Board to abandon the entire line on January 12, 2005.[7] After the tracks and related materials were removed, the subway tunnel under Tucker Boulevard was filled in.[8] Ironhorse Resources then sold the right-of-way and the trestle to Great Rivers Greenway, which plans on converting the trestle and portions of the right-of-way into a pedestrian and bicycle path.[9] The trail system is being called "The Trestle."[10]

The Illinois Terminal Railroad today

[edit]The McKinley Bridge across the Mississippi River, originally built in 1910 to carry the Illinois Traction System's trolley cars over the river to St. Louis, survives to this day. Some sections of the Illinois Terminal Railroad and its affiliated lines have become rail-trails, such as the Interurban Trail south of Springfield.

The Illinois Traction System's generating plants also sold electricity to customers in many towns and cities serviced by the electric railroad. In the 1930s, the railroad and its electrical utility separated from each other. The formerly-affiliated electrical utility was spun off to form the Illinois Power and Light Company. Illinois Power provided electrical service to much of central and southern Illinois before its acquisition by Ameren. Consolidation into the parent firm occurred in 2004.

The Illinois Traction Building in Champaign, Illinois, also known as the Illinois Traction Station and the Illinois Power Building, was built in 1913 and was designed by Joseph Royer. It served as the headquarters of the Illinois Traction System, as well as the Champaign passenger depot. It then became the headquarters of the Illinois Terminal Railway, and, until 1985, Illinois Power and Light. The building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2006.[11]

Norfolk Southern painted NS #1072, an EMD SD70ACe, into the Illinois Terminal scheme in 2012 as a part of the company's 30th anniversary.[12]

Gallery

[edit]-

An Illinois Traction conductor, c. 1912

-

Illinois Terminal 1605, a GP7 preserved in operating condition at Illinois Railway Museum

-

Norfolk Southern 1072, an EMD SD70ACe painted in Illinois Terminal colors, leads an intermodal train through Lewistown, Pennsylvania

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ Fehl, George. "The Illinois Traction System: Comprehensive Traction Maps and Railway Illustrations, Parts One-Four." (G/S Productions, 1992).

- ^ Hilton & Due 1960, p. 62.

- ^ Schafer, Mike (November 2003). "White Elephants under wires". Classic Trains Special Edition. No. 1, Dream Trains. pp. 94–98. ISSN 1541-809X.

- ^ Jenkins, Dale (2005). The Illinois Terminal Railroad: The Road of Personalized Services. Bucklin, Missouri: White River Productions. ISBN 1932804005.

- ^ a b Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Railroad Switching Service of Missouri Freight Train on Illinois Terminal St. Louis Line". YouTube. November 9, 2013.

- ^ Hilton, Zack (May 28, 2006). "Photo Details". LocoPhotos.com. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "Federal Register". Government Information Library. Vol. 70. February 1, 2005.

- ^ O'Neil, Tim. "Limited traffic flows along new Tucker Boulevard, completion set for August". Stltoday.com.

- ^ "The Trestle | Great Rivers Greenway". Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ^ "Saint Louis, Missouri". Abandoned Rails. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ "National Register Information System – (#86003782)". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Norfolk Southern Heritage Locomotives". WVNC Rails. July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hilton, George W.; Due, John Fitzgerald (1960). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4014-2. OCLC 237973.

- A very thorough publication about the interurban transportation industry in general. Covers initial financing, construction, physical structures, cars and equipment, freight business, power generation, impact of the Depression, and decline.

- Middleton, William D. (1961). The Interurban Era. Milwaukee, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. ISBN 978-0-89024-003-8. OCLC 4357897 – via Archive.org.

- A historical review of U.S. interurban railways state by state. Extensive photographs and commentary.

- Young, Andrew (1984). St. Louis Car Company Album {Interurbans Special #91}. Glendale, CA: Interurban Press. ISBN 0916374629.

- St. Louis Car constructed the streamliners in late 1940s that failed to revive Illinois Terminal Railroad's passenger business.

External links

[edit]- Illinois Terminal Railroad heritage society

- Sample Illinois Terminal PCC

- Illinois Terminal System Maps

- Illinois Traction System Photo Gallery, Historical Society of Montgomery County Illinois

- Illinois Terminal Railroad Collection - McLean County Museum of History archives

- Illinois Traction Terminal Collection, McLean County Museum of History

- Champaign-Urbana-Danville Interurban, 1903 Archived 2020-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Switching and terminal railroads

- Defunct Illinois railroads

- Former Class I railroads in the United States

- Interurban railways in Illinois

- Predecessors of the Norfolk and Western Railway

- Railway companies established in 1895

- Streetcars in Greater St. Louis

- Railway companies disestablished in 1922

- Railway companies established in 1937

- Railway companies disestablished in 1982

- Defunct Missouri railroads

- Rail in Greater St. Louis

- Electric railways in Illinois

- Electric railways in Missouri

- American companies established in 1937

- 1895 establishments in Illinois

- American companies established in 1895

- 3300 V AC railway electrification

- 650 V DC railway electrification