The Cheese and the Worms

First UK edition | |

| Author | Carlo Ginzburg |

|---|---|

| Original title | Il formaggio e i vermi |

| Subject | Popular religion and the Counter-Reformation |

| Genre | Microhistory, Histoire des mentalités, Cultural History |

| Published | 1976 Einaudi (Italian) |

| Publication place | Italy |

Published in English | 1980 Routledge & Kegan Paul UK |

| ISBN | 9788806153779 |

The Cheese and the Worms (Italian: Il formaggio e i vermi) is a scholarly work by the Italian historian Carlo Ginzburg, published in 1976. The book is a notable example of the history of mentalities, microhistory, and cultural history. It has been called "probably the most popular and widely read work of microhistory".[1][2]

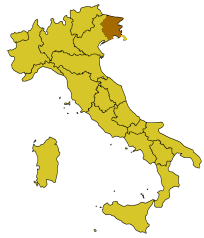

The study examines the unique religious beliefs and cosmogony of Menocchio (1532–1599), also known as Domenico Scandella, who was an Italian miller from the village of Montereale, 25 kilometers north of Pordenone in modern northern Italy. He was from the peasant class, and not a learned aristocrat or man of letters; Ginzburg places him in the tradition of popular culture and pre-Christian naturalistic peasant religions. Due to his outspoken beliefs, he was declared a heresiarch (heretic) and burned at the stake during the Roman Inquisition.

Background

[edit]Carlo Ginzburg first encountered documents related to Domenico Scandella, known as Menocchio, in 1963 while he was researching 16th- and 17th-century witchcraft trials (the subject of his first book) in Friuli, a region in the northeast of Italy. While looking through an index prepared by a local inquisitor, he read a short summary of Menocchio's trial. He returned in 1970 and began to study the documents of the two trials. He published The Cheese and the Worms, his second book, in 1976.[3]

The immediate context of the work was debates about the relationship between popular and high culture, in which Ginzburg became involved during his time as a teacher in Bologna after 1970.[4] Writing in 2013, Ginzburg stated that in hindsight, his decision to write a study of Menocchio's case was rooted in an interest in the relationship between exceptional cases and the general in history. He wrote that his decision to make "[t]he persecuted and the vanquished," traditionally ignored by historians, the subject of his research was a choice that he had made long before he wrote the book, but the choice was strengthened by "the radical political climate of the 1970s."[5]

Menocchio's life

[edit]Education and cultural horizon

[edit]Menocchio's literacy may be on account of schools in the villages surrounding Friuli: Aviano and Pordenone. A school was opened at the beginning of the sixteenth century under the direction of Girolamo Amaseo for, "reading and teaching, without exception, children of citizens as well as those artisans and the lower classes, old as well as young, without payment." It is possible that Menocchio attended a school such as this. He began to read some books available in his locality and began to reinterpret the Bible.

No complete list exists of the books that Menocchio might have read which influenced his view of the cosmos. At the time of his arrest several books were found, but since they were not prohibited, no record was taken. Based on Menocchio's first trial these books are known to have been read:

- 1. The Bible in the vernacular

- 2. Il Fioretto della Bibbia (a translation of a medieval Catalan chronicle compiled from various sources)

- 3. Il Lucidario della Madonna, by the Dominican Albert da Castello

- 4. Il Lucendario de santi, by Jacopo da Voragine (see Golden Legend)

- 5. Historia del giudicio (anonymous fifteenth-century poem)

- 6. Il cavallier Zuanne de Mandavilla (an Italian translation of the book of travels attributed to Sir John Mandeville)

- 7. A book called Zampollo (Il sogno dil Caravia)

Based on the testimony from Menocchio's second trial these books also are known to have been read:

- 8. Il supplimento della cronache

- 9. Lunario al modo di Italia calculato composto nella citta di Pesaro dal. ecc. mo dottore Marino Camilo de Leonardis

- 10. the Decameron of Boccaccio

- 11. an unidentified book believed to be an Italian translation of the Quran

Many of these books were loaned to Menocchio and were common at the time. Knowing how Menocchio read and interpreted these texts might provide insight into his views which led to his execution for proselytizing heretical ideas.

Menocchio's beliefs

[edit]During the preliminary questioning, Menocchio spoke freely because he felt he had done nothing wrong. It is in this hearing that he explained his cosmology about "the cheese and the worms", the title of Carlo Ginzburg's microhistory of Menocchio and source of much that is known of this sixteenth-century miller.

Menocchio said: "I have said that, in my opinion, all was chaos, that is, earth, air, water, and fire were mixed together; and out of that bulk a mass formed – just as cheese is made out of milk – and worms appeared in it, and these were the angels. The most holy majesty decreed that these should be God and the angels, and among that number of angels there was also God, he too having been created out of that mass at the same time, and he was named lord with four captains, Lucifer, Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael. That Lucifer sought to make himself lord equal to the king, who was the majesty of God, and for this arrogance God ordered him driven out of heaven with all his host and his company; and this God later created Adam and Eve and people in great number to take the places of the angels who had been expelled. And as this multitude did not follow God's commandments, he sent his Son, whom the Jews seized, and he was crucified."

Menocchio had a "tendency to reduce religion to morality", using this as justification for his blasphemy during his trial because he believed that the only sin was to harm one's neighbor and that to blaspheme caused no harm to anyone but the blasphemer. He went so far as to say that Jesus was born of man and Mary was not a virgin, that the Pope had no power given to him from God (but simply exemplified the qualities of a good man), and that Christ had not died to "redeem humanity".[6] Warned to denounce his ways and uphold the beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church by both his inquisitors and his family, Menocchio returned to his village. Because of his nature, he was unable to cease speaking about his theological ideas with those who would listen. He had originally attributed his ideas to "diabolical inspiration" and the influence of the devil before admitting that he had simply thought up the ideas himself.

Argument

[edit]Ginzburg uses the case of Menocchio to argue that peasant culture and high culture in preindustrial Europe influenced each other. Drawing from the ideas of the literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, he describes this relationship between the two cultures as "a circular relationship composed of reciprocal influences, which traveled from low to high as well as from high to low."[7]

Ginzburg treats Menocchio's beliefs as a manifestation of a persistent pre-Christian religious current in peasant culture. He notes convergences between the ideas expressed by Menocchio, other contemporary 'heretical' commoners, and representatives of high culture that went against the standards of the Counter-Reformation. Furthermore, Ginzburg argues that Menocchio's beliefs and actions were made possible by the advent of print in Europe and the Protestant Reformation. The printing revolution made books accessible to him, which facilitated the interaction between the oral culture in which he was rooted and the literary culture of the books and gave him the words to express his ideas. Observing that considerable differences exist between Menocchio's references to the books he read and the actual content of those works, Ginzburg argues that Menocchio did not merely adopt ideas that he read in books but rather used elements from those works to articulate his ideas.[8]

The Protestant Reformation brought traditional authorities and doctrines under doubt and thus gave Menocchio the courage to express his ideas, which did not derive from the ideas of the Reformation but rooted in a "substratum of peasant beliefs, perhaps centuries old, that were never wholly wiped out."[9] Ginzburg also sees Menocchio's case as representative of the suppression of the peasant culture that occurred especially starting from the mid-16th century after which, he suggests, the interchange between peasant and high culture declined.[10]

See also

[edit]- The Night Battles (1966), also by Carlo Ginzburg

- The Great Cat Massacre (1984) by Robert Darnton

References

[edit]- ^ Tristano, Richard M. (1996). "Microhistory and Holy Family Parish: Some Historical Considerations". U.S. Catholic Historian. 14 (3): 26.

- ^ Fox-Horton, Julie (November 2015). "Review of Ginzburg, Carlo, The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller". H-Net Reviews. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ^ Ginzburg, Carlo (2013) [First published in Italian 1976]. The Cheese and the Worms. Translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. ix. ISBN 978-1-4214-0988-7.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, pp. xi, xxi–xxii.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, p. x.

- ^ Ginzburg, Carlo (1980). The Cheese and the Worms: The Cosmos of a Sixteenth-Century Miller. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 39, 27, 17, 12.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, p. xx.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, pp. xxxi, 16–19.

- ^ Ginzburg 2013, pp. 119–120.

Further reading

[edit]- Bernard, Yvelise (1988). L'Orient du XVIe siècle: Une société musulmane florissante (in French). Paris: L'Harmattan. pp. 31–37. ISBN 2-7384-0144-9. A short annotated biography of Guillaume Postel.

- Del Col, Andrea, ed. (1996). Domenico Scandella Known as Menocchio: His Trials Before the Inquisition (1583–1599). Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies 139. Translated by John and Anne C. Tedeschi. Binghamton, New York – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) Transcriptions of the documents from Menocchio's trials with a detailed introduction. - Obelkevich, James (1979). Religion and the People, 800–1700. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1332-X.

External links

[edit]- The Cheese and the Worms (1992 English paperback edition) on Internet Archive

- "Putting the Inquisition on Trial", Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1998. Archived 17 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Review in the Journal of Peasant Studies (1983) by William W. Kelly. Archived 9 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine