Iguanodon

| Iguanodon Temporal range: Early Cretaceous (Barremian)

| |

|---|---|

| |

| I. bernissartensis mounted in modern quadrupedal posture, Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, Brussels | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Neornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ornithopoda |

| Family: | †Iguanodontidae |

| Genus: | †Iguanodon Mantell, 1825[1] |

| Type species | |

| †Iguanodon bernissartensis Boulenger in Beneden, 1881

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

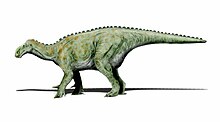

Iguanodon (/ɪˈɡwɑːnədɒn/ i-GWAH-nə-don; meaning 'iguana-tooth'), named in 1825, is a genus of iguanodontian dinosaur. While many species found worldwide have been classified in the genus Iguanodon, dating from the Late Jurassic to Early Cretaceous, taxonomic revision in the early 21st century has defined Iguanodon to be based on one well-substantiated species: I. bernissartensis, which lived during the Barremian to early Aptian ages of the Early Cretaceous in Belgium, Germany, England, and Spain, between about 126 and 122 million years ago. Iguanodon was a large, bulky herbivore, measuring up to 9–11 metres (30–36 ft) in length and 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons) in body mass. Distinctive features include large thumb spikes, which were possibly used for defense against predators, combined with long prehensile fifth fingers able to forage for food.

The genus was named in 1825 by English geologist Gideon Mantell, based on fossil specimens found in England and was given the species name I. anglicus. Iguanodon was the second type of dinosaur formally named based on fossil specimens, after Megalosaurus. Together with Megalosaurus and Hylaeosaurus, it was one of the three genera originally used to define Dinosauria. The genus Iguanodon belongs to the larger group Iguanodontia, along with the duck-billed hadrosaurs. The taxonomy of this genus continues to be a topic of study as new species are named or long-standing ones reassigned to other genera.

In 1878 new, far more complete remains of Iguanodon were discovered in Belgium and studied by Louis Dollo. These were given the new species I. bernissartensis. In the early 21st century it became understood that the remains referred to as Iguanodon in England belonged to four different species (including I. bernissartensis) that were not closely related to each other, which were subsequently split off into Mantellisaurus, Barilium and Hypselospinus. It was also found that the originally described type species of Iguanodon, I. anglicus is now a nomen dubium, and not valid. Thus the name "Iguanodon" became fixed around the well known species based primarily on the Belgian specimens. In 2015, a second valid species, I. galvensis, was named, based on fossils found in the Iberian Peninsula.

Scientific understanding of Iguanodon has evolved over time as new information has been obtained from fossils. The numerous specimens of this genus, including nearly complete skeletons from two well-known bone beds, have allowed researchers to make informed hypotheses regarding many aspects of the living animal, including feeding, movement, and social behaviour. As one of the first scientifically well-known dinosaurs, Iguanodon has occupied a small but notable place in the public's perception of dinosaurs, its artistic representation changing significantly in response to new interpretations of its remains.

Discovery and history

[edit]Gideon Mantell, Sir Richard Owen, and the discovery of dinosaurs

[edit]

The discovery of Iguanodon has long been accompanied by a popular legend. The story goes that Gideon Mantell's wife, Mary Ann, discovered the first teeth[4] of an Iguanodon in the strata of Tilgate Forest in Whitemans Green, Cuckfield, Sussex, England, in 1822 while her husband was visiting a patient. However, there is no evidence that Mantell took his wife with him while seeing patients. Furthermore, he admitted in 1851 that he himself had found the teeth,[5] although he had previously stated in 1827 and 1833 that Mrs. Mantell had indeed found the first of the teeth later named Iguanodon.[6][7] Other later authors agree that the story is not certainly false.[8] It is known from his notebooks that Mantell first acquired large fossil bones from the quarry at Whitemans Green in 1820. Because also theropod teeth were found, thus belonging to carnivores, he at first interpreted these bones, which he tried to combine into a partial skeleton, as those of a giant crocodile. In 1821 Mantell mentioned the find of herbivorous teeth and began to consider the possibility that a large herbivorous reptile was present in the strata. However, in his 1822 publication Fossils of the South Downs he as yet did not dare to suggest a connection between the teeth and his very incomplete skeleton, presuming that his finds presented two large forms, one carnivorous ("an animal of the Lizard Tribe of enormous magnitude"), the other herbivorous.

In May 1822 he first presented the herbivorous teeth to the Royal Society of London but the members, among them William Buckland, dismissed them as fish teeth or the incisors of a rhinoceros from a Tertiary stratum. On 23 June 1823 Charles Lyell showed some to Georges Cuvier, during a soiree in Paris, but the famous French naturalist at once dismissed them as those of a rhinoceros. Though the very next day Cuvier retracted, Lyell reported only the dismissal to Mantell, who became rather diffident about the issue. In 1824 Buckland described Megalosaurus and was on that occasion invited to visit Mantell's collection. Seeing the bones on 6 March he agreed that these were of some giant saurian—though still denying it was a herbivore. Emboldened nevertheless, Mantell again sent some teeth to Cuvier, who answered on 22 June 1824 that he had determined that they were reptilian and quite possibly belonged to a giant herbivore. In a new edition that year of his Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles Cuvier admitted his earlier mistake, leading to an immediate acceptance of Mantell, and his new saurian, in scientific circles. Mantell tried to corroborate his theory further by finding a modern-day parallel among extant reptiles.[9] In September 1824 he visited the Royal College of Surgeons but at first failed to find comparable teeth. However, assistant-curator Samuel Stutchbury recognised that they resembled those of an iguana he had recently prepared, albeit twenty times longer.[10]

In recognition of the resemblance of the teeth to those of the iguana, Mantell decided to name his new animal Iguanodon or 'iguana-tooth', from iguana and the Greek word ὀδών (odon, odontos or 'tooth').[11] Based on isometric scaling, he estimated that the creature might have been up to 18 metres (59 feet) long, more than the 12-metre (39 ft) length of Megalosaurus.[1] His initial idea for a name was Iguana-saurus ('Iguana lizard'), but his friend William Daniel Conybeare suggested that that name was more applicable to the iguana itself, so a better name would be Iguanoides ('Iguana-like') or Iguanodon.[9][12] He neglected to add a specific name to form a proper binomial, but one was supplied in 1829 by Friedrich Holl: I. anglicum, which was later emended to I. anglicus.[13]

Mantell sent a letter detailing his discovery to the local Portsmouth Philosophical Society in December 1824, several weeks after settling on a name for the fossil creature. The letter was read to members of the Society at a meeting on 17 December, and a report was published in the Hampshire Telegraph the following Monday, 20 December, which announced the name, misspelled as "Iguanadon".[14] Mantell formally published his findings on 10 February 1825, when he presented a paper on the remains to the Royal Society of London.[1][5]

A more complete specimen of a similar animal was discovered in a quarry in Maidstone, Kent, in 1834 (lower Lower Greensand Formation), which Mantell soon acquired. He was led to identify it as an Iguanodon based on its distinctive teeth. The Maidstone slab (NHMUK PV OR 3791) was used in the first skeletal reconstructions and artistic renderings of Iguanodon, but due to its incompleteness, Mantell made some mistakes, the most famous of which was the placement of what he thought was a horn on the nose.[15] The discovery of much better specimens in later years revealed that the horn was actually a modified thumb. Still encased in rock, the Maidstone skeleton is currently displayed at the Natural History Museum in London. The borough of Maidstone commemorated this find by adding an Iguanodon as a supporter to their coat of arms in 1949.[16] This specimen has become linked with the name I. mantelli, a species named in 1832 by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in place of I. anglicus, but it actually comes from a different formation than the original I. mantelli/I. anglicus material.[12] The Maidstone specimen, also known as Gideon Mantell's "Mantel-piece", and formally labelled NHMUK 3741[17][18] was subsequently excluded from Iguanodon. It is classified as cf. Mantellisaurus by McDonald (2012);[19] as cf. Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis by Norman (2012);[17] and made the holotype of a separate species Mantellodon carpenteri by Paul (2012),[18] but this is considered dubious and it is generally considered a specimen of Mantellisaurus[20]

At the same time, tension began to build between Mantell and Richard Owen, an ambitious scientist with much better funding and society connections in the turbulent worlds of Reform Act-era British politics and science. Owen, a firm creationist, opposed the early versions of evolutionary science ("transmutationism") then being debated and used what he would soon coin as dinosaurs as a weapon in this conflict. With the paper describing Dinosauria, he scaled down dinosaurs from lengths of over 61 metres (200 feet), determined that they were not simply giant lizards, and put forward that they were advanced and mammal-like, characteristics given to them by God; according to the understanding of the time, they could not have been "transmuted" from reptiles to mammal-like creatures.[21][22]

In 1849, a few years before his death in 1852, Mantell realised that iguanodonts were not heavy, pachyderm-like animals,[23] as Owen was putting forward, but had slender forelimbs. However, since his passing left him unable to participate in the creation of the Crystal Palace dinosaur sculptures, Owen's vision of the dinosaurs became that seen by the public for decades.[21] With Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins, he had nearly two dozen lifesize sculptures of various prehistoric animals built out of concrete sculpted over a steel and brick framework; two iguanodonts (based on the Maidstone specimen), one standing and one resting on its belly, were included. Before the sculpture of the standing iguanodont was completed, he held a banquet for twenty inside it.[24][25][26]

Bernissart mine discoveries and Dollo's new reconstruction

[edit]The largest find of Iguanodon remains to that date occurred on 28 February 1878 in a coal mine at Bernissart in Belgium, at a depth of 322 m (1,056 ft),[27] when two mineworkers, Jules Créteur and Alphonse Blanchard, accidentally hit on a skeleton that they initially took for petrified wood. With the encouragement of Alphonse Briart, supervisor of mines at nearby Morlanwelz, Louis de Pauw on 15 May 1878 started to excavate the skeletons and in 1882 Louis Dollo reconstructed them. At least 38 Iguanodon individuals were uncovered,[28] most of which were adults.[29] In 1882, the holotype specimen of I. bernissartensis became one of the first ever dinosaur skeletons mounted for display. It was put together in a chapel at the Palace of Charles of Lorraine using a series of adjustable ropes attached to scaffolding so that a lifelike pose could be achieved during the mounting process.[17] This specimen, along with several others, first opened for public viewing in an inner courtyard of the palace in July 1883. In 1891 they were moved to the Royal Museum of Natural History, where they are still on display; nine are displayed as standing mounts, and nineteen more are still in the Museum's basement.[27] The exhibit makes an impressive display in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, in Brussels. A replica of one of these is on display at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History and at the Sedgwick Museum in Cambridge. Most of the remains were referred to a new species, I. bernissartensis,[30] a larger and much more robust animal than the English remains had yet revealed. One specimen, IRSNB 1551, was at first referred to the nebulous, gracile I. mantelli, but is currently referred to Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis. The skeletons were some of the first complete dinosaur skeletons known. Found with the dinosaur skeletons were the remains of plants, fish, and other reptiles,[27] including the crocodyliform Bernissartia.[31]

The science of conserving fossil remains was in its infancy, and new techniques had to be improvised to deal with what soon became known as "pyrite disease". Crystalline pyrite in the bones was being oxidized to iron sulphate, accompanied by an increase in volume that caused the remains to crack and crumble. When in the ground, the bones were isolated by anoxic moist clay that prevented this from happening, but when removed into the drier open air, the natural chemical conversion began to occur. To limit this effect, De Pauw immediately, in the mine-gallery, re-covered the dug-out fossils with wet clay, sealing them with paper and plaster reinforced by iron rings, forming in total about six hundred transportable blocks with a combined weight of a hundred and thirty tons. In Brussels after opening the plaster he impregnated the bones with boiling gelatine mixed with oil of cloves as a preservative. Removing most of the visible pyrite he then hardened them with hide glue, finishing with a final layer of tin foil. Damage was repaired with papier-mâché.[32] This treatment had the unintended effect of sealing in moisture and extending the period of damage. In 1932 museum director Victor van Straelen decided that the specimens had to be completely restored again to safeguard their preservation. From December 1935 to August 1936 the staff at the museum in Brussels treated the problem with a combination of alcohol, arsenic, and 390 kilograms of shellac. This combination was intended to simultaneously penetrate the fossils (with alcohol), prevent the development of mold (with arsenic), and harden them (with shellac). The fossils entered a third round of conservation from 2003 until May 2007, when the shellac, hide glue and gelatine were removed and impregnated with polyvinyl acetate and cyanoacrylate and epoxy glues.[33] Modern treatments of this problem typically involve either monitoring the humidity of fossil storage, or, for fresh specimens, preparing a special coating of polyethylene glycol that is then heated in a vacuum pump, so that moisture is immediately removed and pore spaces are infiltrated with polyethylene glycol to seal and strengthen the fossil.[27]

Dollo's specimens allowed him to show that Owen's prehistoric pachyderms were not correct for Iguanodon. He instead modelled the skeletal mounts after the cassowary and wallaby, and put the spike that had been on the nose firmly on the thumb.[34][35] His reconstruction would prevail for a long period of time, but would later be discounted.[27]

Excavations at the quarry were stopped in 1881, although it was not exhausted of fossils, as recent drilling operations have shown.[36] During World War I, when the town was occupied by German forces, preparations were made to reopen the mine for palaeontology, and Otto Jaekel was sent from Berlin to supervise. Just as the first fossiliferous layer was about to be uncovered, however, the German army surrendered and had to withdraw. Further attempts to reopen the mine were hindered by financial problems and were stopped altogether in 1921 when the mine flooded.[27][37]

Turn of the century and the Dinosaur Renaissance

[edit]

Research on Iguanodon decreased during the early part of the 20th century as World Wars and the Great Depression enveloped Europe. A new species that would become the subject of much study and taxonomic controversy, I. atherfieldensis, was named in 1925 by R. W. Hooley, for a specimen collected at Atherfield Point on the Isle of Wight.[38]

Iguanodon was not part of the initial work of the dinosaur renaissance that began with the description of Deinonychus in 1969, but it was not neglected for long. David B. Weishampel's work on ornithopod feeding mechanisms provided a better understanding of how it fed,[39] and David B. Norman's work on numerous aspects of the genus has made it one of the best-known dinosaurs.[28][27][40][41] In addition, a further find of numerous disarticulated Iguanodon bones in Nehden, Nordrhein-Westphalen, Germany, has provided evidence for gregariousness in this genus, as the animals in this areally restricted find appear to have been killed by flash floods. At least 15 individuals, from 2 to 8 metres (6 ft 7 in to 26 ft 3 in) long, have been found here, most of the individuals belong to the related Mantellisaurus (described as I. atherfieldensis, at that time believed to be another species of Iguanodon).[29][42] but some are of I. bernissartensis.

One major revision to Iguanodon brought by the Renaissance would be another re-thinking of how to reconstruct the animal. A major flaw with Dollo's reconstruction was the bend he introduced into the tail. This organ was more or less straight, as shown by the skeletons he was excavating, and the presence of ossified tendons. In fact, to get the bend in the tail for a more wallaby or kangaroo-like posture, the tail would have had to be broken. With its correct, straight tail and back, the animal would have walked with its body held horizontal to the ground, arms in place to support the body if needed.

21st century research and the splitting of the genus

[edit]

In the 21st century, Iguanodon material has been used in the search for dinosaur biomolecules. In research by Graham Embery et al., Iguanodon bones were processed to look for remnant proteins. In this research, identifiable remains of typical bone proteins, such as phosphoproteins and proteoglycans, were found in a rib.[43] In 2007, Gregory S. Paul split I. atherfieldensis into a new, separate genus, Mantellisaurus which has been generally accepted.[44] In 2009 fragmentary iguanodontid material was described from upper Barremian Paris Basin deposits in Auxerre, Burgundy. While not definitively diagnosable to the genus/species level, the specimen shares "obvious morphological and dimensional affinities" with I. bernissartensis.[45]

In 2010, David Norman split the Valanginian species I. dawsoni and I. fittoni into Barilium and Hypselospinus respectively.[46] After Norman 2010, over half a dozen new genera were named off English "Iguanodon" material. Carpenter and Ishida in 2010 named Proplanicoxa, Torilion and Sellacoxa while Gregory S. Paul in 2012 named Darwinsaurus, Huxleysaurus and Mantellodon and Macdonald et al. in 2012 named Kukufeldia. These species named after Norman 2010 are not considered valid and are considered various junior synonyms of Mantellisaurus, Barilium and Hypselospinus.[20]

In 2011, a new genus Delapparentia was named for a specimen in Spain that was originally thought to belong to I. bernissartensis.[3] The previous identification was subsequently reaffirmed in a new analysis of individual variation in the Belgian specimens, finding that the Delapparentia specimen was within the range of I. bernissartensis.[47] In 2015 a new species of Iguanodon, I. galvensis, was named based on material including 13 juvenile (perinate) individuals found in the Camarillas Formation near Galve, Spain.[2] In 2017 a new study was done of I. galvensis, with further evidence of distinctiveness from I. bernissartensis including several new autapomorphies. It was also found that the Delapparentia holotype (which is also from the Camarillas Formation) was not distinguishable from either I. bernissartensis or I. galvensis.[48]

Description

[edit]

Iguanodon were bulky herbivores that could shift from bipedality to quadrupedality.[28] The only well-supported species, I. bernissartensis, is estimated to have measured about 9 metres (30 feet) long as an adult, with some specimens possibly as long as 13 metres (43 feet),[11] although this is likely an overestimate, given that the maximum body length of I. bernissartensis is reported to be 11 m (36 ft).[47] Although Gregory S. Paul suggested a body mass of 3.08 metric tons (3.40 short tons) on average,[10] constructing a 3D mathematical model and employing allometry-based estimate suggests an I. bernissartensis close to 8 m (26 ft) long (smaller than average) weighs close to 3.8 metric tons (4.2 short tons) in body mass.[49][50] Specimens of relatively large individuals have been reported in the 2020s: a specimen referred to as I. cf. galvensis was measured up to 9–10 m (30–33 ft) in length,[51] while a new specimen of I. bernissartensis from the upper Barremian of the Iberian Peninsula was measured up to 11 m (36 ft) in length.[52] Such large individuals would have weighed approximately 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons).[53]

The arms of I. bernissartensis were long (up to 75% the length of the legs) and robust,[11] with rather inflexible hands built so that the three central fingers could bear weight.[28] The thumbs were conical spikes that stuck out away from the three main digits. In early restorations, the spike was placed on the animal's nose. Later fossils revealed the true nature of the thumb spikes,[27] although their exact function is still debated. They could have been used for defense, or for foraging for food. The little finger was elongated and dextrous, and could have been used to manipulate objects. The phalangeal formula is 2-3-3-2-4, meaning that the innermost finger (phalange) has two bones, the next has three, etc.[54] The legs were powerful, but not built for running, and each foot had three toes. The backbone and tail were supported and stiffened by ossified tendons, which were tendons that turned to bone during life (these rod-like bones are usually omitted from skeletal mounts and drawings).[28]

These animals had large, tall but narrow skulls, with toothless beaks probably covered with keratin, and teeth like those of iguanas, as the name suggests, but much larger and more closely packed.[28] Unlike hadrosaurids, which had columns of replacement teeth, Iguanodon only had one replacement tooth at a time for each position. The upper jaw held up to 29 teeth per side, with none at the front of the jaw, and the lower jaw 25; the numbers differ because teeth in the lower jaw are broader than those in the upper.[55] Because the tooth rows are deeply inset from the outside of the jaws, and because of other anatomical details, it is believed that, as with most other ornithischians, Iguanodon had some sort of cheek-like structure, muscular or non-muscular, to retain food in the mouth.[56][57]

Classification and evolution

[edit]

Iguanodon gives its name to the unranked clade Iguanodontia, a very populous group of ornithopods with many species known from the Middle Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous. Aside from Iguanodon, the best-known members of the clade include Dryosaurus, Camptosaurus, Ouranosaurus, and the duck-bills, or hadrosaurs. In older sources, Iguanodontidae was shown as a distinct family.[58][59] This family traditionally has been something of a wastebasket taxon, including ornithopods that were neither hypsilophodontids or hadrosaurids. In practice, animals like Callovosaurus, Camptosaurus, Craspedodon, Kangnasaurus, Mochlodon, Muttaburrasaurus, Ouranosaurus, and Probactrosaurus were usually assigned to this family.[59]

With the advent of cladistic analyses, Iguanodontidae as traditionally construed was shown to be paraphyletic, and these animals are recognised to fall at different points in relation to hadrosaurs on a cladogram, instead of in a single distinct clade.[28][55] Essentially, the modern concept of Iguanodontidae currently includes only Iguanodon. Groups like Iguanodontoidea are still used as unranked clades in the scientific literature, though many traditional iguanodontids are now included in the superfamily Hadrosauroidea. Iguanodon lies between Camptosaurus and Ouranosaurus in cladograms, and is probably descended from a camptosaur-like animal.[28] At one point, Jack Horner suggested, based mostly on skull features, that hadrosaurids actually formed two more distantly related groups, with Iguanodon on the line to the flat-headed hadrosaurines, and Ouranosaurus on the line to the crested lambeosaurines,[60] but his proposal has been rejected.[28][55]

The cladogram below follows an analysis by Andrew McDonald, 2012.[61]

Species

[edit]

Because Iguanodon is one of the first dinosaur genera to have been named, numerous species have been assigned to it. While never becoming the wastebasket taxon several other early genera of dinosaurs (such as Megalosaurus) became, Iguanodon has had a complicated history, and its taxonomy continues to undergo revisions.[62][42][63][64] Although Gregory Paul recommended restricting I. bernissartensis to the famous sample from Bernissart, ornithopod workers like Norman and McDonald have disagreed with Paul's recommendations, except exercising caution when accepting records of Iguanodon from France and Spain as valid.[42][2][65]

I. anglicus was the original type species, but the lectotype was based on a single tooth and only partial remains of the species have been recovered since. In March 2000, the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature changed the type species to the much better known I. bernissartensis, with the new holotype being IRSNB 1534. The original Iguanodon tooth is held at Te Papa Tongarewa, the national museum of New Zealand in Wellington, although it is not on display. The fossil arrived in New Zealand following the move of Gideon Mantell's son Walter there; after the elder Mantell's death, his fossils went to Walter.[66]

Species currently accepted as valid

[edit]Only two species assigned to Iguanodon are still considered to be valid.[28][42]

- I. bernissartensis, described by George Albert Boulenger in 1881, is the type species for the genus. This species is best known for the many skeletons discovered in the Sainte-Barbe Clays Formation at Bernissart, but is also known from remains across Europe.

- Delapparentia turolensis, named in 2011[3] based on a specimen previously assigned to Iguanodon bernissartensis,[67] was argued to be distinct from the latter based on the relative height of its neural spines.[68] However, a 2017 study noted that this is easily within the range of individual variation, and that the difference may also arise from D. turolensis being an adult older than other specimens of I. bernissartensis.[47]

- I. seelyi (also incorrectly spelled I. seeleyi), described by John Hulke in 1882, has also been synonymised with Iguanodon bernissartensis, though this is not universally accepted. It was discovered in Brook, on the Isle of Wight, and named after Charles Seely MP, Liberal politician and philanthropist, on whose estate it was found.[42][69]

- David Norman has suggested that I. bernissartensis includes the dubious Mongolian I. orientalis (see also below),[70] but this has not been followed by other researchers.[42]

- I. galvensis, described in 2015, is based on adult and juvenile remains found in Barremian-age deposits in Teruel, Spain.[2]

Reassigned species of Iguanodon

[edit]

- I. albinus (or Albisaurus scutifer), described by Czech palaeontologist Antonin Fritsch in 1893, is a dubious nondinosaurian reptile now known as Albisaurus albinus.[71]

- I. atherfieldensis, described by R.W. Hooley in 1925,[38] was smaller and less robust than I. bernissartensis, with longer neural spines. It was renamed Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis in 2007.[62] The Bernissart specimen RBINS 1551 was described as Dollodon bampingi in 2008, but McDonald and Norman returned Dollodon to synonymy with Mantellisaurus.[46][72]

- I. dawsoni, described by Lydekker in 1888,[73] is known from two partial skeletons found in East Sussex, England,[28] from the middle Valanginian-age Lower Cretaceous Wadhurst Clay.[42] It is now the type species of Barilium.[46]

- I. exogyrarum was described by Fritsch in 1878. It is a nomen dubium based on very poor material and was renamed Ponerosteus in 2000.[74]

- I. fittoni was described by Lydekker in 1889.[75] Like I. dawsoni, this species was described from the Wadhurst Clay[42] of East Sussex.[28] It is now the type species of Hypselospinus.[46]

- I. hilli, coined by Edwin Tully Newton in 1892 for a tooth from the early Cenomanian Upper Cretaceous Lower Chalk of Hertfordshire, has been considered an early hadrosaurid of some sort.[76] However, recent work places it as indeterminate beyond Hadrosauroidea outside Hadrosauridae.[77]

- I. hoggi (also spelled I. boggii or hoggii), named by Owen for a lower jaw from the Tithonian–Berriasian-age Upper Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous Purbeck Beds of Dorset in 1874, has been reassigned to its own genus, Owenodon.[78]

- I. hollingtoniensis (also spelled I. hollingtonensis), described by Lydekker in 1889, has variously been considered a synonym of Hypselospinus fittoni[28][46] or a distinct species assigned to the genus Huxleysaurus.[18] A specimen from the Valanginian Wadhurst Clay Formation,[18] variously assigned to I. hollingtoniensis and I. mantelli over the years, has an unusual combination of hadrosaurid-like lower jaw and very robust forelimb;[42] Norman (2010) assigned this specimen to the species Hypselospinus fittoni,[46] while Paul (2012) made it the holotype of a separate species Darwinsaurus evolutionis.[18]

- I. lakotaensis was described by David B. Weishampel and Philip R. Bjork in 1989.[79] The only well-accepted North American species of Iguanodon, I. lakotaensis was described from a partial skull from the Barremian-age Lower Cretaceous Lakota Formation of South Dakota. Its assignment has been controversial. Some researchers suggest that it was more basal than I. bernissartensis, and related to Theiophytalia,[80] but David Norman has suggested that it was a synonym of I. bernissartensis.[63] Gregory S. Paul has since given the species its own genus, Dakotadon.[42]

- I. mantelli described by Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer in 1832, was based on the same material as I. anglicus[12] and is an objective junior synonym of the latter.[81] Several taxa, including the holotype of Mantellisaurus and Mantellodon, but also the dubious hadrosauroid Trachodon cantabrigiensis the hypsilophodont Hypsilophodon, and Valdosaurus, were previously mis-assigned to I. mantelli.

- "I. mongolensis" is a nomen nudum from a photo caption in a book by Whitfield in 1992[82] of remains that would later be named Altirhinus.[83]

- I. orientalis, described by A. K. Rozhdestvensky in 1952,[84] was based on poor material, but a skull with a distinctive arched snout that had been assigned to it was renamed Altirhinus kurzanovi in 1998.[63] At the same time, I. orientalis was considered to be a nomen dubium because it cannot be compared to I. bernissartensis.[63][70]

- I. phillipsi was described by Harry Seeley in 1869,[85] but he later reassigned it to Priodontognathus.[86]

- I. praecursor (also spelled I. precursor), described by E. Sauvage in 1876 from teeth from an unnamed Kimmeridgian (Late Jurassic) formation in Pas-de-Calais, France, is actually a sauropod, sometimes assigned to Neosodon,[87] although the two come from different formations.[88]

- I. prestwichii (also spelled I. prestwichi), described by John Hulke in 1880, has been reassigned to Camptosaurus prestwichii or to its own genus Cumnoria.

- I. suessii, described by Emanuel Bunzel in 1871, has been reassigned to Mochlodon suessi.[28]

Species reassigned to Iguanodon

[edit]- I. foxii (also spelled I. foxi) was originally described by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1869 as the type species of Hypsilophodon; Owen (1873 or 1874) reassigned it to Iguanodon, but his assignment was soon overturned.[89]

- I. gracilis, named by Lydekker in 1888 as the type species of Sphenospondylus and assigned to Iguanodon in 1969 by Rodney Steel, has been suggested to be a synonym of Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis,[28] but is considered dubious nowadays.[41][72]

- I. major, a species named by Justin Delair in 1966,[90] based on vertebrae from the Isle of Wight and Sussex originally described by Owen in 1842 as a species of Streptospondylus, S. major, is a nomen dubium.[69]

- I. valdensis, a renaming of Vectisaurus valdensis by Ernst van den Broeck in 1900.[91] Originally named by Hulke as a distinct genus in 1879 based on vertebral and pelvic remains, it was from the Barremian stage of the Isle of Wight.[92] It was considered a juvenile specimen of Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis,[93] or an undetermined species of Mantellisaurus,[42] but is indeterminate beyond Iguanodontia.[72]

- The nomen nudum "Proiguanodon" (van den Broeck, 1900) also belongs here.[94]

Dubious species

[edit]

- I. anglicus, described by Friedrich Holl in 1829,[13] is the original type species of Iguanodon, but, as discussed above, was replaced by I. bernissartensis. In the past, it has been spelled as I. angelicus (Lessem and Glut, 1993) and I. anglicum (Holl, 1829 emend. Bronn, 1850). It is possible teeth ascribed to this species belong to the genus now called Barilium.[95] The name Therosaurus (Fitzinger, 1840),[96] is a junior objective synonym, a later name for the material of I. anglicus.

- I. ottingeri, described by Peter Galton and James A. Jensen in 1979, is a nomen dubium based on teeth from the possibly Aptian-age lower Cedar Mountain Formation of Utah.[97]

Palaeobiology

[edit]Feeding

[edit]

One of the first details noted about Iguanodon was that it had the teeth of a herbivorous reptile,[1] although there has not always been consensus on how it ate. As Mantell noted, the remains he was working with were unlike any modern reptile, especially in the toothless, scoop-shaped form of the lower jaw symphysis, which he found best compared to that of the two-toed sloth and the extinct ground sloth Mylodon. He also suggested that Iguanodon had a prehensile tongue which could be used to gather food,[98] like a giraffe. More complete remains have shown this to be an error; for example, the hyoid bones that supported the tongue are heavily built, implying a muscular, non-prehensile tongue used for moving food around in the mouth.[40] The giraffe-tongue idea has also been incorrectly attributed to Dollo via a broken lower jaw.[99]

The skull was structured in such a way that as it closed, the bones holding the teeth in the upper jaw would bow out. This would cause the lower surfaces of the upper jaw teeth to rub against the upper surface of the lower jaw's teeth, grinding anything caught in between and providing an action that is the rough equivalent of mammalian chewing.[39] Because the teeth were always replaced, the animal could have used this mechanism throughout its life, and could eat tough plant material.[100] Additionally, the front ends of the animal's jaws were toothless and tipped with bony nodes, both upper and lower,[28] providing a rough margin that was likely covered and lengthened by a keratinous material to form a cropping beak for biting off twigs and shoots.[27] Its food gathering would have been aided by its flexible little finger, which could have been used to manipulate objects, unlike the other fingers.[28]

Exactly what Iguanodon ate with its well-developed jaws is not known. The size of the larger species, such as I. bernissartensis, would have allowed them access to food from ground level to tree foliage at 4–5 metres (13–16 ft) high.[11] A diet of horsetails, cycads, and conifers was suggested by David Norman,[27] although iguanodonts in general have been tied to the advance of angiosperm plants in the Cretaceous due to the dinosaurs' inferred low-browsing habits. Angiosperm growth, according to this hypothesis, would have been encouraged by iguanodont feeding because gymnosperms would be removed, allowing more space for the weed-like early angiosperms to grow.[101] The evidence is not conclusive, though.[28][102] Whatever its exact diet, due to its size and abundance, Iguanodon is regarded as a dominant medium to large herbivore for its ecological communities.[28] In England, this included the small predator Aristosuchus, larger predators Eotyrannus, Baryonyx, and Neovenator, low-feeding herbivores Hypsilophodon and Valdosaurus, fellow "iguanodontid" Mantellisaurus, the armoured herbivore Polacanthus, and sauropods like Pelorosaurus.[103]

Posture and movement

[edit]

Early fossil remains were fragmentary, which led to much speculation on the posture and nature of Iguanodon. Iguanodon was initially portrayed as a quadrupedal horn-nosed beast. However, as more bones were discovered, Mantell observed that the forelimbs were much smaller than the hindlimbs. His rival Owen was of the opinion it was a stumpy creature with four pillar-like legs. The job of overseeing the first lifesize reconstruction of dinosaurs was initially offered to Mantell, who declined due to poor health, and Owen's vision subsequently formed the basis on which the sculptures took shape. Its bipedal nature was revealed with the discovery of the Bernissart skeletons. However, it was depicted in an upright posture, with the tail dragging along the ground, acting as the third leg of a tripod.[104]

During his re-examination of Iguanodon, David Norman was able to show that this posture was unlikely, because the long tail was stiffened with ossified tendons.[40] To get the tripodal pose, the tail would literally have to be broken.[27] Putting the animal in a horizontal posture makes many aspects of the arms and pectoral girdle more understandable. For example, the hand is relatively immobile, with the three central fingers grouped together, bearing hoof-like phalanges, and able to hyperextend. This would have allowed them to bear weight. The wrist is also relatively immobile, and the arms and shoulder bones robust. These features all suggest that the animal spent time on all fours.[40]

Furthermore, it appears that Iguanodon became more quadrupedal as it got older and heavier; juvenile I. bernissartensis have shorter arms than adults (60% of hindlimb length versus 70% for adults).[28] When walking as a quadruped, the animal's hands would have been held so that the palms faced each other, as shown by iguanodontian trackways and the anatomy of this genus's arms and hands.[105][106] The three-toed pes (foot) of Iguanodon was relatively long, and when walking, both the hand and the foot would have been used in a digitigrade fashion (walking on the fingers and toes).[28] The maximum speed of Iguanodon has been estimated at 24 km/h (15 mph),[107] which would have been as a biped; it would not have been able to gallop as a quadruped.[28]

Large three-toed footprints are known in Early Cretaceous rocks of England, particularly Wealden beds on the Isle of Wight, and these trace fossils were originally difficult to interpret. Some authors associated them with dinosaurs early on. In 1846, E. Tagert went so far as to assign them to an ichnogenus he named Iguanodon,[108] and Samuel Beckles noted in 1854 that they looked like bird tracks, but might have come from dinosaurs.[109] The identity of the trackmakers was greatly clarified upon the discovery in 1857 of the hind leg of a young Iguanodon, with distinctly three-toed feet, showing that such dinosaurs could have made the tracks.[110][111] Despite the lack of direct evidence, these tracks are often attributed to Iguanodon.[27] A trackway in England shows what may be an Iguanodon moving on all fours, but the foot prints are poor, making a direct connection difficult.[40] Tracks assigned to the ichnogenus Iguanodon are known from locations including places in Europe where the body fossil Iguanodon is known, to Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway.[112][113]

Thumb spike

[edit]

The thumb spike is one of the best-known features of Iguanodon. Although it was originally placed on the animal's nose by Mantell, the complete Bernissart specimens allowed Dollo to place it correctly on the hand, as a modified thumb.[104] (This would not be the last time a dinosaur's modified thumb claw would be misinterpreted; Noasaurus, Baryonyx, and Megaraptor are examples since the 1980s where an enlarged thumb claw was first put on the foot, as in dromaeosaurids.[114][115])

This thumb is typically interpreted as a close-quarter stiletto-like weapon against predators,[28][27] although it could also have been used to break into seeds and fruits,[28] or against other Iguanodon.[11] One author has suggested that the spike was attached to a venom gland,[116][117] but this has not been accepted, as the spike was not hollow,[11] nor were there any grooves on the spike for conducting venom.[118][nb 1]

Possible social behaviour

[edit]

Although sometimes interpreted as the result of a single catastrophe, the Bernissart finds instead are now interpreted as recording multiple events. According to this interpretation, at least three occasions of mortality are recorded, and though numerous individuals would have died in a geologically short time span (?10–100 years),[29] this does not necessarily mean these Iguanodon were herding animals.[28]

An argument against herding is that juvenile remains are very uncommon at this site, unlike modern cases with herd mortality. They more likely were the periodic victims of flash floods whose carcasses accumulated in a lake or marshy setting.[29] The Nehden find, however, with its greater span of individual ages, more even mix of Dollodon or Mantellisaurus to Iguanodon bernissartensis, and confined geographic nature, may record mortality of herding animals migrating through rivers.[29]

There is no evidence that Iguanodon was sexually dimorphic (with one sex appreciably different from the other).[47] At one time, it was suggested that the Bernissart I. "mantelli", or I. atherfieldensis (Dollodon and Mantellisaurus, respectively) represented a sex, possibly female, of the larger and more robust, possibly male, I. bernissartensis.[119] However, this is not supported today.[27][40][62] A 2017 analysis showed that I. bernissartensis does exhibit a large level of individual variation in both its limbs (scapula, humerus, thumb claw, ilium, ischium, femur, tibia) and spinal column (axis, sacrum, tail vertebrae). Additionally, this analysis found that individuals of I. bernissartensis generally seemed to fall into two categories based on whether their tail vertebrae bore a furrow on the bottom, and whether their thumb claws were large or small.[47]

Paleopathology

[edit]Evidence of a fractured hip bone was found in a specimen of Iguanodon, which had an injury to its ischium. Two other individuals were observed with signs of osteoarthritis as evidenced by bone overgrowths in their anklebones which are called osteophytes.[120]

In popular culture

[edit]

Since its description in 1825, Iguanodon has been a feature of worldwide popular culture. Two lifesize reconstructions of Mantellodon (considered Iguanodon at the time) built at the Crystal Palace in London in 1852 greatly contributed to the popularity of the genus.[121] Their thumb spikes were mistaken for horns, and they were depicted as elephant-like quadrupeds, yet this was the first time an attempt was made at constructing full-size dinosaur models. In 1910 Heinrich Harder portrayed a group of Iguanodon in Tiere der Urwelt, a classic German collecting card game about extinct and prehistoric animals.

Several motion pictures have featured Iguanodon. In the 2000 Disney animated film Dinosaur, an Iguanodon named Aladar served as the protagonist with three other iguanodonts as other main and minor characters are Neera, Kron and Bruton. A loosely related ride of the same name at Disney's Animal Kingdom is based around bringing an Iguanodon back to the present.[122] Iguanodon is one of the three dinosaur genera that inspired Godzilla; the other two were Tyrannosaurus rex and Stegosaurus.[123] Iguanodon has also made appearances in some of the many The Land Before Time films, as well as episodes of the television series.

Aside from appearances in movies, Iguanodon has also been featured on the television documentary miniseries Walking with Dinosaurs (1999) produced by the BBC (along with then-undescribed Dakotadon lakotaensis) and played a starring role in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's book The Lost World as well as featuring in the 2015 documentary Dinosaur Britain. It also was present in Bob Bakker's Raptor Red (1995), as a Utahraptor prey item. A main belt asteroid, 1989 CB3, has been named 9941 Iguanodon in honour of the genus.[124][125]

Because it is both one of the first dinosaurs described and one of the best-known dinosaurs, Iguanodon has been well-placed as a barometer of changing public and scientific perceptions on dinosaurs. Its reconstructions have gone through three stages: the elephantine quadrupedal horn-snouted reptile satisfied the Victorians, then a bipedal but still fundamentally reptilian animal using its tail to prop itself up dominated the early 20th century, but was slowly overturned during the 1960s by its current, more agile and dynamic representation, able to shift from two legs to all fours.[126]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Naish's works cite Tweedie (1977) as the source of the venomous spike proposal, but this work does not explicitly attribute venom to Iguanodon, only noting on page 69 that there is no hard-tissue evidence for venom in stingray tails and platypus spurs.[117] Elting and Goodman (1987:46) explicitly report a venom spike proposal, attributing it to "one scientist".[116]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Mantell, Gideon A. (1825). "Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate forest, in Sussex". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 115: 179–186. Bibcode:1825RSPT..115..179M. doi:10.1098/rstl.1825.0010. ISSN 0261-0523. JSTOR 107739.

- ^ a b c d Verdú, Francisco J.; Royo-Torres, Rafael; Cobos, Alberto; Alcalá, Luis (2015). "Perinates of a new species of Iguanodon (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from the lower Barremian of Galve (Teruel, Spain)". Cretaceous Research. 56: 250–264. Bibcode:2015CrRes..56..250V. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.05.010.

- ^ a b c Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I. (2011). "Delapparentia turolensis nov. gen et sp., un nuevo dinosaurio iguanodontoideo (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) en el Cretácico Inferior de Galve". Estudios Geológicos. 67: 83–110. doi:10.3989/egeol.40276.124.

- ^ "Collections Online – Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa". collections.tepapa.govt.nz. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ^ a b Sues, Hans-Dieter (1997). "European Dinosaur Hunters". In James Orville Farlow; M. K. Brett-Surman (eds.). The Complete Dinosaur. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-253-33349-0.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon (1827). Illustrations of the Geology of Sussex. London: Lupton Relfe. pp. 71–78.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon (1833). "Description of the Organic Remains of the Wealden, and particularly of those of the Strata of Tilgate Forest". The Geology of the South East of England. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–288.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Dean, Dennis R. (December 1999). "Book review: Gideon Mantell and the discovery of dinosaurs". PALAIOS. 14 (6): 601–602. Bibcode:1999Palai..14..601L. doi:10.2307/3515316. ISSN 0883-1351. JSTOR 3515316.

- ^ a b Cadbury, D. (2000). The Dinosaur Hunters. Fourth Estate:London, 384 p. ISBN 1-85702-959-3.

- ^ a b Glut, Donald F. (1997). "Iguanodon". Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. pp. 490–500. ISBN 978-0-89950-917-4.

- ^ a b c d e f Naish, Darren; Martill, David M. (2001). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. London: The Palaeontological Association. pp. 60–132. ISBN 978-0-901702-72-2.

- ^ a b c Olshevsky, G. "Re: Hello and a question about Iguanodon mantelli (long)". Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ^ a b Holl, Friedrich (1829). Handbuch der Petrifaktenkunde, Vol. I. Ouedlinberg. Dresden: P.G. Hilscher. OCLC 7188887.

- ^ Simpson, M.I. (2015). "Iguanodon is older than you think: the public and private announcements of Gideon Mantell's giant prehistoric herbivorous reptile". Deposits Magazine. 44: 33.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon A. (1834). "Discovery of the bones of the Iguanodon in a quarry of Kentish Rag (a limestone belonging to the Lower Greensand Formation) near Maidstone, Kent". Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal. 17: 200–201.

- ^ Colbert, Edwin H. (1968). Men and Dinosaurs: The Search in Field and Laboratory. New York: Dutton & Company. ISBN 978-0-14-021288-4.

- ^ a b c Norman, David B. (2012). "Iguanodontian taxa (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the Lower Cretaceous of England and Belgium". In Godefroit, P. (ed.). Bernissart Dinosaurs and Early Cretaceous Terrestrial Ecosystems. Indiana University Press. pp. 175–212. ISBN 978-0-253-35721-2.

- ^ a b c d e Paul, G. S. (2012). "Notes on the rising diversity of Iguanodont taxa, and Iguanodonts named after Darwin, Huxley, and evolutionary science" Actas de V Jornadas Internacionales sobre Paleontología de Dinosaurios y su Entorno, Salas de los Infantes, Burgos. pp. 123–133.

- ^ McDonald, Andrew T. (2012). "The status of Dollodon and other basal iguanodonts (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Wealden beds (Lower Cretaceous) of Europe". Cretaceous Research. 33 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.03.002.

- ^ a b Norman, David B. (December 2013). "On the taxonomy and diversity of Wealden iguanodontian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda)" (PDF). Revue de Paléobiologie, Genève. 32 (2): 385–404. ISSN 0253-6730. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ a b Torrens, Hugh. "Politics and Paleontology". The Complete Dinosaur, 175–190.

- ^ Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British Fossil Reptiles: Part II". Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science for 1841. 1842: 60–204.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon A. (1851). Petrifications and their teachings: or, a handbook to the gallery of organic remains of the British Museum. London: H. G. Bohn. OCLC 8415138.

- ^ Benton, Michael S. (2000). "brief history of dinosaur paleontology". In Gregory S. Paul (ed.). The Scientific American Book of Dinosaurs. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 10–44. ISBN 978-0-312-26226-6.

- ^ Yanni, Carla (September 1996). "Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 55 (3): 276–299. doi:10.2307/991149. JSTOR 991149.

- ^ Norman, David B. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Norman, David B. (1985). "To Study a Dinosaur". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: An Original and Compelling Insight into Life in the Dinosaur Kingdom. New York: Crescent Books. pp. 24–33. ISBN 978-0-517-46890-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Norman, David B. (2004). "Basal Iguanodontia". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 413–437. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ a b c d e Norman, David B. (March 1987). "A mass-accumulation of vertebrates from the Lower Cretaceous of Nehden (Sauerland), West Germany". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 230 (1259): 215–255. Bibcode:1987RSPSB.230..215N. doi:10.1098/rspb.1987.0017. PMID 2884670. S2CID 22329180.

- ^ I.e. "from Bernissart".

- ^ Palmer, D. ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 100 ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ^ De Pauw, L.F., 1902, Notes sur les fouilles du charbonnage de Bernissart, Découverte, solidification et montage des Iguanodons, Imprim. photo-litho, JH. & P. Jumpertz, 150 av.d'Auderghem. 25 pp

- ^ Pascal Godefroit & Thierry Leduc, 2008, "La conservation des ossements fossiles : le cas des Iguanodons de Bernissart", Conservation, Exposition, Restauration d'Objets d'Art 2 (2008)

- ^ Dollo, Louis (1882). "Première note sur les dinosauriens de Bernissart". Bulletin du Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique (in French). 1: 161–180.

- ^ Dollo, Louis (1883). "Note sur les restes de dinosauriens recontrés dans le Crétacé Supérieur de la Belgique". Bulletin du Musée Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique (in French). 2: 205–221.

- ^ de Ricqlès, A. (2003). "Bernissart's Iguanodon: the case for "fresh" versus "old" dinosaur bone". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 23 (Supplement to Number 3): 1–124. doi:10.1080/02724634.2003.10010538. ISSN 0272-4634. S2CID 220410105. Abstracts of Papers, Sixty-Third Annual Meeting.

- ^ Cordier, S (2017). De botten van de Borinage. De iguanodons van Bernissart van 125 miljoen voor Christus tot vandaag. Antwerpen: Vrijdag ISBN 9789460014871. [page needed]

- ^ a b Hooley, R. W. (1925). "On the skeleton of Iguanodon atherfieldensis sp. nov., from the Wealden Shales of Atherfield (Isle of Wight)". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 81 (2): 1–61. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1925.081.01-04.02. ISSN 0370-291X. S2CID 129181645.

- ^ a b Weishampel, David B. (1984). "Introduction". Evolution of Jaw Mechanisms in Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Advances in Anatomy, Embryology, and Cell Biology, 87. Vol. 87. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–109. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-69533-9_1. ISBN 978-0-387-13114-6. PMID 6464809.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Norman, David B. (1980). "On the ornithischian dinosaur Iguanodon bernissartensis of Bernissart (Belgium)" (PDF). Mémoires de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique. 178: 1–105.

- ^ a b Norman, David B. (1986). "On the anatomy of Iguanodon atherfieldensis (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda)". Bulletin de l'Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Sciences de la Terre. 56: 281–372. ISSN 0374-6291.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Paul, Gregory S. (2008). "A revised taxonomy of the iguanodont dinosaur genera and species" (PDF). Cretaceous Research. 29 (2): 192–216. Bibcode:2008CrRes..29..192P. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2007.04.009.

- ^ Embery, Graham; Milner, Angela C.; Waddington, Rachel J.; Hall, Rachel C.; Langley, Martin S.; Milan, Anna M. (2003). "Identification of proteinaceous material in the bone of the dinosaur Iguanodon". Connective Tissue Research. 44 (Suppl. 1): 41–46. doi:10.1080/03008200390152070. PMID 12952172. S2CID 2249126.

- ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2007). "Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 69–78. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1zxz1md.9. ISBN 978-0-253-02795-5. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Knoll, Fabien (November 2009). "A large iguanodont from the Upper Barremian of the Paris Basin". Geobios. 42 (6): 755–764. Bibcode:2009Geobi..42..755K. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2009.06.002.

- ^ a b c d e f Norman, David B. (2010). "A taxonomy of iguanodontians (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the lower Wealden Group (Cretaceous: Valanginian) of southern England" (PDF). Zootaxa. 2489: 47–66. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2489.1.3.

- ^ a b c d e Verdú, F.J.; Godefroit, P.; Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2017). "Individual variation in the postcranial skeleton of the Early Cretaceous Iguanodon bernissartensis (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda)". Cretaceous Research. 74: 65–86. Bibcode:2017CrRes..74...65V. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2017.02.006.

- ^ Verdú, Francisco Javier; Royo-Torres, Rafael; Cobos, Alberto; Alcalá, Luis (19 May 2018). "New systematic and phylogenetic data about the early Barremian Iguanodon galvensis (Ornithopoda: Iguanodontoidea) from Spain". Historical Biology. 30 (4): 437–474. Bibcode:2018HBio...30..437V. doi:10.1080/08912963.2017.1287179. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 89715643.

- ^ Henderson, D.M. (1999). "Estimating the Masses and Centers of Mass of Extinct Animals by 3-D Mathematical Slicing". Paleobiology. 25 (1): 88–106. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(1999)025<0088:ETMACO>2.3.CO;2 (inactive 1 November 2024). JSTOR 2665994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Seebacher, F. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.255. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 4524171. S2CID 53446536.

- ^ Verdú, F.J.; Royo-Torres, R.; Cobos, A.; Alcalá, L. (2021). "Systematics and paleobiology of a new articulated axial specimen referred to Iguanodon cf. galvensis (Ornithopoda, Iguanodontoidea)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 40 (6): e1878202. doi:10.1080/02724634.2021.1878202. S2CID 233829292.

- ^ Gasulla, J.M.; Escaso, F.; Narváez, I.; Sanz, J.L.; Ortega, F. (2022). "New Iguanodon bernissartensis Axial Bones (Dinosauria, Ornithopoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Morella, Spain". Diversity. 14 (2): 63. doi:10.3390/d14020063.

- ^ Nye, E.; Feist-Burkhardt, S.; Horne, D.J.; Ross, A.J.; Whittaker, J.E. (2008). "The palaeoenvironment associated with a partial Iguanodon skeleton from the Upper Weald Clay (Barremian, Early Cretaceous) at Smokejacks Brickworks (Ockley, Surrey, UK), based on palynomorphs and ostracods". Cretaceous Research. 29 (3): 417–444. Bibcode:2008CrRes..29..417N. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2008.01.004.

- ^ Martin, Anthony J. (2006). Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs (Second ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. p. 560. ISBN 1-4051-3413-5..

- ^ a b c Norman, David B.; Weishampel, David B. (1990). "Iguanodontidae and related ornithopods". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 510–533. ISBN 978-0-520-06727-1.

- ^ Galton, Peter M. (1973). "The cheeks of ornithischian dinosaurs". Lethaia. 6 (1): 67–89. Bibcode:1973Letha...6...67G. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1973.tb00873.x.

- ^ Fastovsky, D.E., and Smith, J.B. "Dinosaur paleoecology." The Dinosauria, 614–626.

- ^ Galton, Peter M. (September 1974). "Notes on Thescelosaurus, a conservative ornithopod dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous of North America, with comments on ornithopod classification". Journal of Paleontology. 48 (5): 1048–1067. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1303302.

- ^ a b Norman, David B. "Iguanodontidae". The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, 110–115.

- ^ Horner, J. R. (1990). "Evidence of diphyletic origination of the hadrosaurian (Reptilia: Ornithischia) dinosaurs". In Kenneth Carpenter; Phillip J. Currie (eds.). Dinosaur Systematics: Perspectives and Approaches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–187. ISBN 978-0-521-36672-4.

- ^ McDonald, A. T. (2012). Farke, Andrew A (ed.). "Phylogeny of Basal Iguanodonts (Dinosauria: Ornithischia): An Update". PLOS ONE. 7 (5): e36745. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...736745M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036745. PMC 3358318. PMID 22629328.

- ^ a b c Paul, Gregory S. (2007). "Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England". In Kenneth Carpenter (ed.). Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 69–77. ISBN 978-0-253-34817-3.

- ^ a b c d Norman, David B. (January 1998). "On Asian ornithopods (Dinosauria, Ornithischia). 3. A new species of iguanodontid dinosaur". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 122 (1–2): 291–348. doi:10.1006/zjls.1997.0122.

- ^ Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M. (2002). "Ornithischian dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous (Berriasian) of England". In Milner, Andrew; Batten, David J. (eds.). Life and Environments in Purbeck Times. Special Papers in Palaeontology. Vol. 68. London: Palaeontological Association. pp. 161–189. ISBN 978-0-901702-73-9.

- ^ Norman, David B. (2011). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". In Batten, D. J. English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London). pp. 407–475.

- ^ Royal Society of New Zealand. "Celebrating the great fossil hunters". Archived from the original on 26 August 2005. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Albert-Félix de Lapparent (1960). "Los dos dinosaurios de Galve". Teruel. 24: 177–197.

- ^ Gasca, J.M.; Moreno-Azanza, M.; Ruiz-Omeñaca, J.I.; Canudo, J.I. (2015). "New material and phylogenetic position of the basal iguanodont dinosaur Delapparentia turolensis from the Barremian (Early Cretaceous) of Spain" (PDF). Journal of Iberian Geology. 41 (1). doi:10.5209/rev_jige.2015.v41.n1.48655.

- ^ a b Naish, Darren; Martill, David M. (2008). "Dinosaurs of Great Britain and the role of the Geological Society of London in their discovery: Ornithischia". Journal of the Geological Society, London. 165 (3): 613–623. Bibcode:2008JGSoc.165..613N. doi:10.1144/0016-76492007-154. S2CID 129624992.

- ^ a b Norman, David B. (March 1996). "On Asian ornithopods (Dinosauria, Ornithischia). 1. Iguanodon orientalis Rozhdestvensky, 1952". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 116 (2): 303–315. doi:10.1006/zjls.1996.0021.

- ^ Brikman, Winand (1988). Zur Fundgeschichte und Systematik der Ornithopoden (Ornithischia, Reptilia) aus der Ober-Kreide von Europa. Documenta Naturae, 45 (in German). Munich: Kanzler. ISBN 978-3-86544-045-7.

- ^ a b c McDonald, Andrew T. (2011). "The status of Dollodon and other basal iguanodonts (Dinosauria: Ornithischia) from the upper Wealden beds (Lower Cretaceous) of Europe". Cretaceous Research. 33 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2011.03.002.

- ^ Lydekker, Richard (1888). "Note on a new Wealden iguanodont and other dinosaurs". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 44 (1–4): 46–61. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1888.044.01-04.08. S2CID 129803661.

- ^ Olshevsky, George (2000). "An annotated checklist of dinosaur species by continent". Mesozoic Meanderings. Mesozoic Meanderings, 3. San Diego: G. Olshevsky Publications Requiring Research. ISSN 0271-9428. OCLC 44433611.

- ^ Lydekker, Richard (1889). "On the remains and affinities of five genera of Mesozoic reptiles". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 45 (1–4): 41–59. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1889.045.01-04.04. S2CID 128586645.

- ^ Horner, John R., David B. Weishampel and Catherine A. Forster. "Hadrosauridae". The Dinosauria, pp 438–463.

- ^ Barrett, P., D. C. Evans, and J J. Head, 2014. A re-evaluation of purported hadrosaurid dinosaur specimens from the 'middle' Cretaceous of England In The Hadrosaurs: Proceedings of the International Hadrosaur Symposium (D. A. Eberth and D. C. Evans, eds), Indiana University Press, Bloomington.

- ^ Galton, Peter M. (2009). "Notes on Neocomian (Late Cretaceous) ornithopod dinosaurs from England – Hypsilophodon, Valdosaurus, "Camptosaurus", "Iguanodon" – and referred specimens from Romania and elsewhere". Revue de Paléobiologie. 28 (1): 211–273.

- ^ Weishampel, David B.; Bjork, Phillip R. (1989). "The first indisputable remains of Iguanodon (Ornithischia: Ornithopoda) from North America: Iguanodon lakotaensis, sp. nov". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 9 (1): 56–66. Bibcode:1989JVPal...9...56W. doi:10.1080/02724634.1989.10011738.

- ^ Brill, Kathleen and Kenneth Carpenter. "A description of a new ornithopod from the Lytle Member of the Purgatoire Formation (Lower Cretaceous) and a reassessment of the skull of Camptosaurus." Horns and Beaks, 49–67.

- ^ Norman, David B. (2011). "Ornithopod dinosaurs". In Batten, D. J. (ed.). English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London). pp. 407–475.

- ^ Philip Whitfield, 1992, Children's Guide to Dinosaurs and other Prehistoric Animals, Simon & Schuster pp. 96

- ^ Olshevsky, G. "Dinosaurs of China, Mongolia, and Eastern Asia [under Altirhinus]". Archived from the original on 13 February 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ^ Rozhdestvensky, Anatoly K. (1952). Открытие игуанодона в Монголии [Discovery of an iguanodon in Mongolia]. Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 84 (6): 1243–1246.

- ^ Seeley, Harry G. (1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell, and Co. OCLC 7743994.

- ^ Seeley, Harry G. (1875). "On the maxillary bone of a new dinosaur (Priodontognathus phillipsii), contained in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 31 (1–4): 439–443. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1875.031.01-04.30. S2CID 129113503.

- ^ Sauvage, H. E. (1888). "Sur les reptiles trouvés dans le Portlandian supérieur de Boulogne-sur-mer". Bulletin du Muséum National d'Historie Naturalle, Paris (in French). 3 (16): 626.

- ^ Upchurch, Paul, Paul M. Barrett, and Peter Dodson. "Sauropoda". The Dinosauria

- ^ Woodward, Henry (1885). "On Iguanodon mantelli, Meyer". Geological Magazine. Series 3. 2 (1): 10–15. Bibcode:1885GeoM....2...10W. doi:10.1017/S0016756800188211. OCLC 2139602. S2CID 140635773.

- ^ Delair, J.B. (1966). "New records of dinosaurs and other fossil reptiles from Dorset". Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society. 87: 57–66.

- ^ Van den Broeck, Ernst, 1900, "Les dépôts à iguanodons de Bernissart et leur transfert dans l'étage purbeckien ou aquilonien du Jurassique Supérieur" Bulletin de la Société Belge Géologique XIV Mem., 39–112

- ^ Galton, P.M. (1976). "The Dinosaur Vectisaurus valdensis (Ornithischia: Iguanodontidae) from the Lower Cretaceous of England". Journal of Paleontology. 50 (5): 976–984. JSTOR 1303593.

- ^ Norman, David B. (30 November 1990), Carpenter, Kenneth; Currie, Philip J. (eds.), "A review of Vectisaurus valdensis , with comments on the family Iguanodontidae", Dinosaur Systematics (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 147–162, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511608377.014, ISBN 978-0-521-36672-4, retrieved 29 December 2019

- ^ Olshevsky, G. "Re: What are these dinosaurs?". Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ^ Norman, David B. (2011). "On the osteology of the lower wealden (valanginian) ornithopod barilium dawsoni (iguanodontia: styracosterna)". Special Papers in Palaeontology. 86: 165–194. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- ^ Fitzinger, L. J. (1840). "Über Palaeosaurus sternbergii, eine neue Gattung vorweltlicher Reptilien und die Stellung dieser Thiere im Systeme überhaupt". Wiener Museum Annalen. II: 175–187.

- ^ Galton, Peter; Jensen, James A. (1979). "Galton, P. M., & Jensen, J. A. (1979). Remains of ornithopod dinosaurs from the Lower Cretaceous of North America" (PDF). Brigham Young University Geology Studies. 25 (3): 1–10. ISSN 0068-1016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Mantell, Gideon A. (1848). "On the structure of the jaws and teeth of the Iguanodon". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 138: 183–202. doi:10.1098/rstl.1848.0013. JSTOR 111004. S2CID 110141217.

- ^ Norman, D.B. (1985). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, 115.

- ^ Bakker, Robert T. (1986). "Dinosaurs At Table". The Dinosaur Heresies. Vol. 2. New York: William Morrow. pp. 160–178. Bibcode:1987Palai...2..523G. doi:10.2307/3514623. ISBN 978-0-14-010055-6. JSTOR 3514623.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Bakker, R.T. "When Dinosaurs Invented Flowers". The Dinosaur Heresies, 179–198

- ^ Barrett, Paul M.; Willis, K. J. (2001). "Did dinosaurs invent flowers? Dinosaur–angiosperm coevolution revisited" (PDF). Biological Reviews. 76 (3): 411–447. doi:10.1017/S1464793101005735. PMID 11569792. S2CID 46135813.

- ^ Weishampel, D.B., Barrett, P.M., Coria, R.A., Le Loeuff, J., Xu Xing, Zhao Xijin, Sahni, A., Gomani, E.M.P., and Noto, C.R. "Dinosaur Distribution". The Dinosauria, 517–606.

- ^ a b Norman, David B. (2005). Dinosaurs: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192804198.

- ^ Wright, J. L. (1996). Fossil terrestrial trackways: Preservation, taphonomy, and palaeoecological significance (PhD thesis). University of Bristol. pp. 1–300.

- ^ Wright, J. L. (1999). "Ichnological evidence for the use of the forelimb in iguanodontians". In Unwin, David M. (ed.). Cretaceous Fossil Vertebrates. Special Papers in Palaeontology. Vol. 60. Palaeontological Association. pp. 209–219. ISBN 978-0-901702-67-8.

- ^ Coombs, Walter P. Jr. (1978). "Theoretical aspects of cursorial adaptations in dinosaurs". Quarterly Review of Biology. 53 (4): 393–418. doi:10.1086/410790. ISSN 0033-5770. JSTOR 2826581. S2CID 84505681.

- ^ Tagert, E. (1846). "On markings in the Hastings sands near Hastings, supposed to be the footprints of birds". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 2 (1–2): 267. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1846.002.01-02.45. S2CID 128406306.

- ^ Beckles, Samuel H. (1854). "On the ornithoidichnites of the Wealden". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 10 (1–2): 456–464. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1854.010.01-02.52. S2CID 197536154.

- ^ Owen, Richard (1858). "Monograph on the Fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations. Part IV. Dinosauria (Hylaeosaurus)". Paleontographical Society Monograph. 10 (43): 1–26. doi:10.1080/02693445.1858.12027916.

- ^ "Bird-Footed Iguanodon, 1857". Paper Dinosaurs 1824–1969. Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering & Technology. Archived from the original on 28 September 2006. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

- ^ Glut, Donald F. (2003). Dinosaurs: The Encyclopedia. 3rd Supplement. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 626. ISBN 978-0-7864-1166-5.

- ^ Lapparent, Albert-Félix de (1962). "Footprints of dinosaurs in the Lower Cretaceous of Vestspitsbergen — Svalbard". Arbok Norsk Polarinstitutt, 1960: 13–21.

- ^ Agnolin, F. L.; Chiarelli, P. (2009). "The position of the claws in Noasauridae (Dinosauria: Abelisauroidea) and its implications for abelisauroid manus evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 84 (2): 293–300. doi:10.1007/s12542-009-0044-2. S2CID 84491924.

- ^ Novas, F. E. (1998). "Megaraptor namunhuaiquii, gen. Et sp. Nov., a large-clawed, Late Cretaceous theropod from Patagonia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (1): 4–9. Bibcode:1998JVPal..18....4N. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011030.

- ^ a b Elting, Mary; Goodman, Ann (1987). Dinosaur Mysteries. New York, New York: Platt & Munk. p. 46. ISBN 0448192160. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ a b Tweedie, Michael W.F. (1977). The World of the Dinosaurs. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-688-03222-7.

- ^ Naish, D. "Venomous & Septic Bites". Archived from the original on 9 December 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2007.

- ^ van Beneden, P.J. (1878). "Sur la découverte de reptiles fossiles gigantesques dans le charbonnage de Bernissart, près de Pruwelz". Bulletin de l'Institut Royal d'Histoire Naturelle de Belgique. 3 (1): 1–19.

- ^ Hitt, Jack (1 September 2006). "Doctor to the Dinosaurs". Discover Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Smith, Dan (26 February 2001). "A site for saur eyes". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Radulovic, Petrana (26 December 2019). "Dinosaur is still the scariest ride at Disney World". Polygon. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Snider, Mike (29 August 2006). "Godzilla arouses atomic terror". USA Today. Gannett Corporation. Retrieved 21 February 2007.

- ^ "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: 9941 Iguanodon (1989 CB3)". NASA. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Williams, Gareth. "Minor Planet Names: Alphabetical List". Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G. (2000). Dinosaurs: The Textbook. Boston: McGraw-Hill. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-07-303642-7.

External links

[edit]- The Bernissart Iguanodons (Iguanodon herd found in Belgium).

- Mantell's Iguanodon tooth in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Iguanodonts

- Barremian genus first appearances

- Aptian genus extinctions

- Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of Europe

- Fossils of Belgium

- Fossils of Spain

- Camarillas Formation

- Fossil taxa described in 1825

- Taxa named by Gideon Mantell

- Ornithischian genera

- Multispecific non-avian dinosaur genera

- Fossils of Germany

- Fossils of England

- Cretaceous Germany

- Cretaceous England

- Early Cretaceous ornithopods

- Ornithopods of Europe