Icos

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| Industry | Biotechnology |

| Founded | Bothell, Washington, U.S. (1989) |

| Founder | George Rathmann Robert Nowinski Christopher Henney |

| Defunct | 29 January 2007 |

| Fate | Acquired, Dissolved |

| Successor | CMC ICOS Biologics, Inc. |

| Headquarters | , United States |

Key people | George Rathmann (Founder, CEO, Chairman) Paul Clark (CEO, Chairman) |

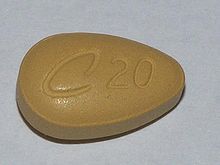

| Products | Cialis |

| Revenue | US$ 71,410,000 (2005)[1] |

| US$ −74,242,000 (2005)[1] | |

| US$ −74,842,000 (2005)[1] | |

| Total assets | US$ 241,767,000 (2005)[1] |

| Total equity | US$ −59,270,000 (2005)[1] |

Number of employees | 700 (2006) |

Icos Corporation (trademark ICOS) was an American biotechnology company and the largest biotechnology company in the U.S. state of Washington, before it was sold to Eli Lilly and Company in 2007. It was founded in 1989 by David Blech, Isaac Blech, Robert Nowinski, and George Rathmann, a pioneer in the industry and chief executive officer (CEO) and co-founder of Amgen.[2] Icos focused on the development of drugs to treat inflammatory disorders. During its 17-year history, the company conducted clinical trials of twelve drugs, three of which reached the last phase of clinical trials. Icos also manufactured antibodies for other biotechnology companies.

Icos is best known for the development of tadalafil (Cialis), a drug used to treat erectile dysfunction. This drug was discovered by GlaxoSmithKline, developed by Icos, and manufactured and marketed in partnership with Eli Lilly. Boosted by a unique advertising campaign led by the Grey Worldwide Agency, sales from Cialis allowed Icos to become profitable in 2006. Cialis was the only drug developed by the company to be approved.[3] LeukArrest, a drug to treat shock, and Pafase, developed for sepsis, were both tested in phase III clinical trials, but testing was discontinued after unpromising results during the trials. Eli Lilly acquired Icos in January 2007, and most of Icos's workers were laid off soon after.[4] CMC Biologics, a Danish contract manufacturer, bought the remnants of Icos and retained the remaining employees.[4]

History

[edit]

Icos was founded in 1989 by George Rathmann, Robert Nowinski, and Christopher Henney, each of whom had previously started another biotechnology company: Rathmann had created Amgen; Nowinski had launched Genetic Systems, later sold to Bristol-Myers Squibb; and Henney co-founded Immunex, later sold to Amgen.[5] Icos was formed with the goal of developing new drugs to treat the underlying causes of inflammatory diseases and halt the disease process in the early stages.[5] The name Icos comes from icosahedron, a 20-sided polyhedron, which is the shape of many viruses,[2] and was chosen because the founders originally thought retroviruses might be involved in inflammation.[6] The founders raised $33 million in July 1990 from many investors, including Bill Gates – who at the time was the largest shareholder, with 10% of the equity.[5] The company initially had temporary offices in downtown Seattle, but moved to Bothell in September 1990. Icos went public on June 6, 1991, raising $36 million.[7] George Rathmann, seen as a guiding father to Icos, left the company in February 2000, and was replaced as CEO and chairman by Paul Clark, a former executive at Abbott Laboratories.[8][9] A former Icos manager named short-sighted leadership by Clark as a factor in the failure of the company to develop any other successful drugs apart from Cialis.[3]

Cialis

[edit]Sold as Cialis and initially codenamed IC351,[10] tadalafil is a drug prescribed for erectile dysfunction (ED) and approved for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). It is a phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitor, similar in function to sildenafil.[10] In addition to ED and PAH, tadalafil has undergone clinical trials for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia and for female sexual dysfunction.[11][12]

Tadalafil was initially formulated by Glaxo Wellcome (now GlaxoSmithKline) under a new drug development partnership between Glaxo and Icos that began in August 1991.[13][14] The drug was originally researched as a treatment for cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and angina,[13] but focus quickly shifted to ED with the success of another PDE5 inhibitor, sildenafil (Viagra), which had been developed by Pfizer.[2] Icos began research on tadalafil in 1993, and clinical trials started two years later.[10] Glaxo let the partnership with Icos lapse in 1996, including the company's 50% share of profits from resulting drugs, because the drugs in development were not in Glaxo's core markets.[2] In 1998, Icos formed a 50/50 joint venture with Indianapolis-based Eli Lilly (Lilly Icos LLC) to develop and commercialize tadalafil as Cialis.[11] The release of Cialis in the United States was delayed in April 2002 when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended that Icos perform more studies, improve labelling, and address manufacturing issues.[10] Cialis was approved in Europe in November 2002 and in the United States a year later.[10] The drug was approved for once-daily use for ED in Europe in June 2007 and in the United States in January 2008.[15][16]

In 2006, Cialis generated $971 million in sales,[16] leading Icos to post its first-ever quarterly profit in August.[3] In May 2009, tadalafil, to be sold as Adcirca by United Therapeutics, was approved in the United States for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension based on data from a pivotal study begun before the sale of Icos to Eli Lilly.[17][18]

Lawsuits with Pfizer

[edit]Pfizer and Lilly Icos have filed many lawsuits against each other in various countries over Cialis and Viagra. Pfizer was given a broad patent on PDE5 inhibitors in Britain in 1993.[19] Lilly Icos filed a complaint in a London court in September 1999, and the patent was overturned in November 2000 on the grounds that Pfizer's patent was based on information already in the public domain when the patent was issued.[19][20] In the United States, Pfizer filed suit against Lilly Icos soon after receiving a broad US patent for PDE5 inhibitors in October 2002.[21] The United States Patent and Trademark Office ordered a reexamination of the patent, and, as in Britain, the examiner found that PDE5 inhibitors were not a new invention by Pfizer, voiding the patent.[22] In Canada, Pfizer moved to block sales of Cialis five months after it was approved there, arguing that there could be consumer backlash against Pfizer should Cialis be pulled from the market months later as a result of an ongoing patent lawsuit.[23] A federal judge refused, saying he could not "imagine demonstrations in the street or storming of the barricades because one impotence medicine is made unavailable".[23]

Blindness warning on label

[edit]In May 2005, the FDA began investigating reports of sudden blindness in users of sildenafil (Viagra).[24] The FDA said it had received reports of the condition, a permanent blindness in one eye known as non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, in 38 users of sildenafil and 5 users of tadalafil or vardenafil (Levitra).[24] Lilly Icos voluntarily amended the Cialis label to warn of the condition.[24] The FDA was criticized for its handling of the matter, as an FDA safety officer had commented on unusual reports of blindness over 13 months before a journal article was published on the issue.[24] United States Senator Chuck Grassley wrote a letter to the FDA detailing his criticism, saying that the FDA's Office of New Drugs (OND) had taken no action "despite OND's knowledge of the blindness risks since January 2004 and general agreement among FDA staff last spring that the label should be updated".[24] Grassley's letter also suggested that Pfizer resisted adding the blindness warning to Viagra's label.[24] In July 2005, the FDA said that Viagra, Levitra, and Cialis labels would all carry warnings on the risk of sudden blindness, though it was unclear whether the drugs were actually causing the blindness.[25]

Marketing

[edit]

Lilly Icos hired the Grey Worldwide Agency in New York, part of the Grey Global Group, to run the Cialis advertising campaign.[26] Cialis advertisements were described as being gentler, warmer and with a more relaxed feel than those of its rivals, to reflect the longer duration of the drug.[26] (Tadalafil has a half-life of 17.5 hours, compared to 3.5 for sildenafil and 4.5 for vardenafil.) Iconic themes in Cialis advertisements include couples in bathtubs and the slogan "When the moment is right, will you be ready?"[26] Cialis advertisements were unique among those of ED drugs in that they went beyond describing ED and mentioning the drug's benefits.[27] As a result, Cialis advertisements were also the first to describe side effects, as the FDA requires advertisements in support of a specific brand name to mention side effects; ads for Levitra and Viagra did not mention the brand name of the drug, therefore circumventing this FDA requirement.[28] One of the first advertisements for Cialis aired during the 2004 Super Bowl; Lilly Icos paid more than $4 million for the one-minute ad.[27] Just weeks before the game, the FDA required more possible side effects, including priapism, to be listed in the advertisement.[27] Although many parents objected to the ad being aired during the Super Bowl, Janet Jackson's halftime "wardrobe malfunction" overshadowed Cialis.[27] In January 2006, a physician was added to the advertisements to describe side effects on-screen, and Icos began running advertisements only where more than 90 percent of the audience was made up of adults, effectively ending Super Bowl advertisements.[28] In 2004, Lilly Icos, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline spent a combined $373.1 million to advertise Cialis, Viagra, and Levitra respectively.[27]

Miscellaneous drugs

[edit]Icos developed several drugs whose purpose was to disrupt the process of inflammation in the body.[2] The research program focused on the underlying causes of inflammation rather than specific disorders.[2] The compounds developed by Icos were tested in clinical trials in the areas of sepsis, multiple sclerosis, ischemic stroke, heart attack, pancreatitis, pulmonary arterial hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, interstitial cystitis, psoriasis, hemorrhagic shock, sexual dysfunction, benign prostatic hyperplasia, rheumatoid arthritis, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

LeukArrest

[edit]Rovelizumab, trade-named LeukArrest and also known as Hu23F2G,[29] was developed to treat patients with hemorrhagic shock, which is caused by massive blood loss.[30] The drug is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the recruitment of white blood cells to the site of inflammation.[31] During testing, few patients were given the drug, because LeukArrest had to be administered within four hours of the injury and informed consent was required;[32] patients were often unconscious, and relatives had to be reached to give consent.[32] In June 1998, Icos and many medical centers asked the FDA to waive consent requirements in situations where the patient was at high risk of dying and relatives could not be reached.[33] While some medical ethicists opposed waiving consent,[33] the FDA approved the proposal in August 1998 for five medical centers.[34] Development of LeukArrest was halted in April 2000 when interim data from phase III clinical trials did not meet Icos's goals[35] of significantly reducing the chance of multiple organ failure and reducing the death rate from shock at 28 days.[30] LeukArrest was also tested unsuccessfully for treatment of heart attack, multiple sclerosis, and stroke.[36]

Pafase

[edit]Pafase, also known as rPAF-AH, was developed to treat severe sepsis.[37] Pafase is the recombinant form of platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH, also known as lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2), an enzyme made naturally by macrophages and found in human blood.[38] PAF-AH inactivates platelet-activating factor, a phospholipid that plays a role in the inflammation seen in sepsis.[37][39] The enzyme was discovered in the mid-1980s by graduate student Diana Stafforini and researchers Steve Prescott, Guy Zimmerman, and Tom McIntyre at the University of Utah.[38][40] The gene that codes for Pafase was discovered by Icos.[41] Early trials for sepsis showed that the drug reduced the death rate after 28 days and patients were less likely to develop severe respiratory problems.[37] Icos also tested Pafase for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).[38] In phase II trials for ARDS, Pafase reduced the death rate after 28 days and reduced the chance that the lungs of the patient would fail.[38] However, Icos halted development in December 2002 when interim data from phase III trials for sepsis showed that the drug did not help patients survive.[37] Scientists at Northwestern University later studied Pafase for necrotizing enterocolitis,[42] and there is ongoing research on the enzyme for atherosclerosis at the University of Utah.[43]

Sitaxentan sodium and TBC3711

[edit]In June 2000, Icos and Texas Biotechnology formed a 50/50 partnership to research endothelin receptor antagonists for use in the areas of pulmonary hypertension and chronic heart failure.[44] Two drugs, sitaxentan sodium (also spelled sitaxsentan) and TBC3711, were tested in clinical trials under the partnership.[45] Sitaxentan was designed to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension, and TBC3711 was designed to treat cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension.[46] In April 2003, Icos sold its part of the 50/50 partnership, including any share of sitaxentan and TBC3711, to Texas Biotechnology for $4 million at closing and another $6 million within 18 months.[45] Sitaxentan sodium was later approved in Europe, Canada, and Australia, and was marketed under the brand name Thelin.[47] In 2010, Thelin was voluntarily withdrawn from the market worldwide due to concerns about irreversible liver damage.

Other drugs tested in clinical trials

[edit]Icos tested many other drugs that were not approved. They are:

- ICM3, an antibody blocking ICAM-3,[48] designed to treat psoriasis.[2]

- IC14, an antibody blocking CD14, designed to treat sepsis.[37][49]

- IC747 and IC776, two LFA-1 antagonists, designed to treat psoriasis.[50][51]

- Resiniferatoxin (RTX), a naturally occurring capsaicin analog, designed to treat interstitial cystitis.[52][53]

- IC485, a PDE4 inhibitor, designed to treat emphysema, chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and rheumatoid arthritis.[53][54]

- IC83, a CHK-1 inhibitor,[55] designed to enhance chemotherapy.[51]

Manufacturing

[edit]Icos manufactured many antibodies for various companies. In August 2001, the company partnered with Seattle Genetics to manufacture a component of their top experimental antibody drug SGN-15.[56] In November 2001, Icos signed a production agreement with GPC Biotech to manufacture a class of GPC's antibodies that targeted B-cell lymphomas.[57] In January 2002, Icos signed an agreement with Eos Biotechnology,[58] under which Icos would produce Eos's most promising monoclonal antibody candidate, and Eos would have non-exclusive rights to Icos's CHEF1 enhanced mammalian protein production technology.[58] Eos's antibody inhibited angiogenesis (the formation of new blood vessels) and was being researched as a treatment for solid tumors.[58] In October 2003, Icos partnered with Protein Design Labs to manufacture their M200 antibody.[59]

Acquisition by Eli Lilly

[edit]

After Icos's experimental drugs failed in clinical trials, Eli Lilly was in a prime position to purchase the company. In October 2006, Eli Lilly announced that it had reached terms to acquire Icos for $2.1 billion, or $32 a share.[3] After receiving pressure from large institutional shareholders as well as proxy advisory firm Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) suggesting the deal should be rejected, Lilly increased its offer to $2.3 billion or $34 per share, a 6% increase.[60] Again, resistance was voiced by some large shareholders, and ISS advised shareholders against accepting the new offer, which it still deemed insufficient.[61] On January 25, 2007, at a special meeting, 77% of the shareholders voted in support of the acquisition.[62] Eli Lilly closed the transaction to acquire Icos for $2.3 billion on January 29, 2007.[63]

As a result of the acquisition, Eli Lilly gained complete ownership of Cialis, and promptly shut down Icos operations and laid off Icos personnel, except for 127 employees working at the biologics facility.[4][64] Icos was the largest biotechnology company in the state of Washington at the time of the acquisition, and employed around 700 people.[4][65] In December 2007, CMC Biopharmaceuticals A/S, a Copenhagen-based provider of contract biomanufacturing services, bought the Bothell biologics facility and retained the existing 127 employees.[4]

Controversy

[edit]In addition to the layoff of Icos employees, other aspects of the acquisition were equally controversial, such as assertions that Icos was being sold too cheaply and that conflicts of interest existed.[66] The latter related to Icos senior executives, who – despite poor stock performance, in part from failed clinical development programs and an inability to successfully license drugs over the preceding years – were to be massively compensated upon a successful acquisition.[67][68]

Senior executives at Icos received cash payments worth a combined $67.8 million for selling the company to Eli Lilly.[68] Icos chairman, chief executive, and president Paul Clark received "a 'golden parachute' worth $23.2 million in severance pay, cashed-out stock options, restricted stock awards and other bonuses for retention and closing the deal."[68] Nine senior Icos executives received similar packages, each worth more than $1 million.[68]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "ICOS Corporation Annual Report". Securities and Exchange Commission. March 8, 2006. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ervin, Keith (June 21, 1998). "Deep Pockets + Intense Research + Total Control = The Formula—Bothell Biotech Icos Keeps The Pipeline Full Of Promise". The Seattle Times. p. F1. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Timmerman, Luke (October 18, 2006). "Icos Sale a Blow to Local Biotech". The Seattle Times. p. A1. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Tartakoff, Joseph (December 4, 2007). "New owner will invest $50 million in Icos facility". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. E1. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ a b c Erickson, Jim (July 3, 1990). "Top Scientists Form Biotech Firm; Gates is Largest Shareholder as Investors Come Up With $33 Million". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ "Interview with George Rathmann, Icos Corporation". The Wall Street Transcript. April 27, 1999. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ^ "Icos Offering Is A Success". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. July 7, 1991. p. E1.

- ^ Lee, Tyrone (February 2, 2000). "Guiding Father of Icos Cuts Cord". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ "Icos Names Paul Clark President, Chief Executive". The Seattle Times. June 16, 1999. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Cook, John (November 22, 2003). "36-hour Erection Drug Cialis Gets U.S. Approval". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. A1. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Pollack, Andrew (October 2, 1998). "Lilly Pays Big Fee Up Front To Share in Rival of Viagra". The New York Times. p. C5. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "ICOS Corporation Reports Results for 2005 First Quarter; Tadalafil to be Evaluated in a Pivotal Clinical Study in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension". Business Wire. May 5, 2005. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Daugan A, Grondin P, Ruault C, Le Monnier de Gouville AC, Coste H, Kirilovsky J, Hyafil F, Labaudinière R (October 9, 2003). "The discovery of tadalafil: a novel and highly selective PDE5 inhibitor. 1: 5,6,11,11a-tetrahydro-1H-imidazo[1',5':1,6]pyrido[3,4-b]indole-1,3(2H)-dione analogues". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 46 (21): 4525–32. doi:10.1021/jm030056e. PMID 14521414.

- ^ Richards, Rhonda (September 17, 1991). "ICOS At A Crest On Roller Coaster". USA Today. p. 3B.

- ^ Hirschler, Ben (June 25, 2007). "Europe Approves Once-Daily Cialis For Impotence". Reuters. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ a b "Eli Lilly Gets FDA Nod For New Once-Daily Dosing Option Of Erectile Dysfunction Drug Cialis". Associated Press. January 8, 2008.

- ^ Rosenwald, Michael (June 1, 2009). "Local Drugmaker Found Great Partner in Eli Lilly". The Washington Post. p. A10. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "PHIRST-1: Tadalafil in the Treatment of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension". ClinicalTrials.gov. February 13, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2009.

- ^ a b "British Court Overturns a Viagra Patent". The New York Times. November 9, 2000. p. C10. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

- ^ Watts, Mark; Jennie Matthew (September 5, 1999). "UK Court Battle for Viagra". Sunday Business.

- ^ "Pfizer Sues Viagra 'Copycats'". Toronto Star. October 24, 2002. p. D03.

- ^ "Non-final Office Action" (PDF). United States Patent and Trademark Office. September 15, 2005. Retrieved August 19, 2009. Use 90/007,478 for the application number.

- ^ a b Bell, Andrew (April 30, 2004). "The Lawsuit Also Rises". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaufman, Marc (July 1, 2005). "FDA Was Told of Viagra-Blindness Link Months Ago; Senator Criticizes Delay in Alerting Consumers After Safety Officer Warned Agency About Drug". The Washington Post. p. A02. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ Kaufman, Marc (July 9, 2005). "Impotence Drugs Will Get Blindness Warning". The Washington Post. p. A06. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ a b c Elliott, Stuart (April 25, 2004). "Viagra and the Battle of the Awkward Ads". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e McCarthy, Shawn (March 5, 2005). "First they tried to play it safe; Ads for erectile dysfunction drug Cialis bared all – including a scary potential side effect. It was risky but it has paid off". The Globe and Mail. p. B4.

- ^ a b Elliott, Stuart (January 10, 2006). "For Impotence Drugs, Less Wink-Wink". The New York Times. p. C2. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ Mohr, J. P.; Choi, Dennis W.; Grotta, James C. (2004). Stroke: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1044–1045. ISBN 978-0-443-06600-9. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Reed, Kristin (June 15, 1999). "Icos Shares Skid After Drug Fails Test in Treating Shock". The Seattle Times. p. C7. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ Becker K (August 2002). "Anti-leukocyte antibodies: LeukArrest (Hu23F2G) and Enlimomab (R6.5) in acute stroke". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 18 (Suppl 2): s18–22. doi:10.1185/030079902125000688. PMID 12365824. S2CID 35685091.

- ^ a b Gorlick, Arthur (August 29, 1997). "New 'Trauma Drug' is Saving Lives; Hope Comes For Severely Injured Patients". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. C1.

- ^ a b Lerner, Maura (June 23, 1998). "HCMC Seeks Feedback On Plans To Test Trauma Drug; Doctors Hope to Test a Medicine That Could Save Lives of Patients Who Are Unable to Speak For Themselves". Star Tribune. p. 1A.

- ^ "Community consultation and public disclosure information for waiver of Informed Consent" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. August 27, 1998. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "Icos Halts Stroke-Drug Study After Late Results Disappoint". The Seattle Times. April 21, 2000. p. C6. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ "Icos shares tumble on phase II results of LeukArrest". Reuters Health Medical News. June 16, 1999.

- ^ a b c d e "Icos Drug Pafase Hits a Dead End". The Seattle Times. December 20, 2002. p. D1. Archived from the original on September 23, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Siegel, Lee (June 1, 2000). "New Drug Holds Hope Against Lung Ailment". The Salt Lake Tribune. p. C2.

- ^ Schuster DP, Metzler M, Opal S, Lowry S, Balk R, Abraham E, Levy H, Slotman G, Coyne E, Souza S, Pribble J (June 2003). "Recombinant platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase to prevent acute respiratory distress syndrome and mortality in severe sepsis: Phase IIb, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled, clinical trial". Critical Care Medicine. 31 (6): 1612–9. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000063267.79824.DB. PMID 12794395.

- ^ Stafforini DM, McIntyre TM, Carter ME, Prescott SM (March 25, 1987). "Human Plasma Platelet-activating Factor Acetylhydrolase". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 262 (9): 4215–22. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)61335-3. PMID 3549727. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ Tjoelker T, et al. (April 6, 1995). "Anti-inflammatory properties of a platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase". Nature. 374 (6522): 549–53. Bibcode:1995Natur.374..549T. doi:10.1038/374549a0. PMID 7700381. S2CID 4338858.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (December 16, 2006). "Another Clinical Trial Near From Icos Pipeline". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ Stafforini DM (February 2009). "Biology of Platelet-activating Factor Acetylhydrolase (PAF-AH, Lipoprotein Associated Phospholipase A2)". Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy. 23 (1): 73–83. doi:10.1007/s10557-008-6133-8. PMID 18949548. S2CID 21413645.

- ^ Beason, Tyrone (June 7, 2000). "Icos teams with Texas biotech for drug trials". The Seattle Times. p. C3. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "Bothell biotech's partner makes additional investment". The Seattle Times. April 24, 2003. p. E3. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Web Cloaking Service Promises Anonymity". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. December 21, 2000. p. C2.

- ^ "Encysive jumps 17% on higher Thelin guidance". Pharma Marketletter. December 18, 2007.

- ^ Ligocki M, Mackeen L, Axtelle T, Trueblood E, Hensley K, Stucki A, Sandmaier BM, Hayflick JS (July 1, 2000). "Anti-tumor activity of an ICAM-3 antibody (ICM3) against human leukemic xenograft tumors in nude mice". Experimental Hematology. 28 (7): 59–60. doi:10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00274-5.

- ^ Axtelle T, Pribble J (August 2001). "IC14, a CD14 specific monoclonal antibody, is a potential treatment for patients with severe sepsis". Journal of Endotoxin Research. 7 (4): 310–4. doi:10.1177/09680519010070040201. PMID 11717588.

- ^ "Icos Psoriasis Treatment Falls Short". Puget Sound Business Journal. June 6, 2003. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Timmerman, Luke (December 7, 2006). "Icos starts trial of drug, opts not to disclose it". The Seattle Times. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ^ "A Phase 2, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of the Safety and Efficacy of RTX Topical Solution in Patients With Interstitial Cystitis". ClinicalTrials.gov. June 23, 2005. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b Timmerman, Luke (January 14, 2004). "Icos chief stirs up interest in Cialis at investor event". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "Tech Briefs". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. November 6, 2001. p. D2. Retrieved January 12, 2009.

- ^ "Array BioPharma Reports Financial Results for the Fourth Quarter and Full Year of Fiscal 2007". Business Wire. August 6, 2007. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "Microsoft again presses for court delay". The Seattle Times. August 15, 2001. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ "Icos to manufacture antibodies for German biotech". Puget Sound Business Journal. November 26, 2001. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Eos Biotechnology and ICOS Sign Manufacturing and Licensing Agreements; ICOS to Manufacture Eos' Lead Antibody Candidate Targeting Angiogenesis". PR Newswire. January 9, 2002.

- ^ "Icos to Manufacture Clinical Candidate for Protein Design Labs". Business Wire. October 9, 2003. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ "Lilly Increases Offer for Icos; Shareholders' Vote Is Put Off". The New York Times. December 19, 2006. p. C10. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (January 13, 2007). "Reject Icos offer, holders of shares advised". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ James, Andrea (January 26, 2007). "Icos voters approve buyout by Eli Lilly". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. C1. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ "Eli Lilly completes Icos takeover". The Seattle Times. January 30, 2007. p. C1. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (December 12, 2006). "All Icos workers losing their jobs". The Seattle Times. p. C1. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Cook, John (October 20, 2006). "Icos' gain is Seattle's loss". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. p. C1. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2009.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (November 7, 2006). "Proposed Icos sale gets more criticism: Payouts for execs called "overkill"". The Seattle Times. p. C1. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (October 21, 2006). "Icos sale to enrich top executives". The Seattle Times. p. E1. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Timmerman, Luke (November 2, 2006). "Icos leaders to get $68 million from company's sale". The Seattle Times. p. C1. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

External links

[edit]

- Biotechnology companies established in 1989

- Eli Lilly and Company

- Defunct companies based in Bothell, Washington

- Biotechnology companies disestablished in 2007

- Pharmaceutical companies disestablished in 2007

- 2007 mergers and acquisitions

- Biotechnology companies of the United States

- 1989 establishments in Washington (state)

- 2007 disestablishments in Washington (state)