Aquitanian language

| Aquitanian | |

|---|---|

| ᚹᛏᛊ𐋀 | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [ɐ̞ʊ̯s̻k͈o] |

| Native to | France, Spain |

| Region | Western/Central Pyrenees, Gascony |

| Extinct | by the Early Middle Ages (except in the Northern Basque Country) |

| Iberian | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xaq |

xaq | |

| Glottolog | None |

The Aquitanian language was the language of the ancient Aquitani, spoken on both sides of the western Pyrenees in ancient Aquitaine (approximately between the Pyrenees and the Garonne, in the region later known as Gascony) and in the areas south of the Pyrenees in the valleys of the Basque Country before the Roman conquest.[1] It probably survived in Aquitania north of the Pyrenees until the Early Middle Ages.

Archaeological, toponymical, and historical evidence shows that it was a language or group of languages that represent a precursor of the Basque language.[2][3] The most important pieces of evidence are a series of votive and funerary texts in Latin, dated to the first three centuries AD,[4] which contain about 400 personal names and 70 names of gods.

History

[edit]

Aquitanian and its modern relative, Basque, are commonly thought to be Pre-Indo-European languages, remnants of the languages spoken in Western Europe before the arrival of Indo-European speakers.[2] Some claims have been made, based on supposed derivations of the words for "knife" (aizto), "axe" (aizkora) and "hoe" (aitzur) from the word for "stone" (haitz), that the language therefore must date to the Stone Age or Neolithic period, when those tools were made of stone,[5][6] but these etymologies are no longer accepted by mainstream Vasconists.[7]

Persons' names and gods' names

[edit]Almost all of the Aquitanian inscriptions that have been found north of the Pyrenees are in the territory that Greek and Roman sources assigned to Aquitanians.

- Anthroponyms: Belexeia, Lavrco, Borsei, Andereseni, Nescato, Cissonbonnis, Sembecconi, Gerexo, Bihossi, Talsconis, Halscotarris, etc.

- Theonyms: Baigorixo, Ilunno, Arixoni, Artahe, Ilurberrixo, Astoiluno, Haravsoni, Leherenno, etc.

Some inscriptions have also been found south of the Pyrenees in the territory that Greek and Roman sources assigned to Vascones:

- Anthroponyms: Ummesahar, Ederetta, Serhuhoris, Dusanharis, Abisunhar, etc.

- Theonyms: Larrahe, Loxae / Losae, Lacubegi, Selatse / Stelaitse, Helasse, Errensae.

Relations with other languages

[edit]Most Aquitanian onomastic elements are clearly identifiable from a Basque perspective, matching closely the forms reconstructed by the vascologist Koldo Mitxelena for Proto-Basque:

| Aquitanian | Proto-Basque | Basque | Basque meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| adin | *adiN | adin | age, judgment |

| andere, er(h)e | *andere | andre | lady, woman |

| andos(s), andox | *andoś | lord | |

| arix | *aris | aritz | oak |

| artahe, artehe | *artehe | arte | holm oak |

| atta | *aTa | aita | father |

| belex | ?*beLe | bele | crow |

| bels | *bels | beltz | black |

| bihox, bihos | *bihos | bihotz | heart |

| bon, -pon | *boN | on | good |

| bors | *bors | bost | five |

| cis(s)on, gison | *gisoN | gizon | man |

| -c(c)o | *-Ko | -ko | diminutive suffix |

| corri, gorri | *goRi | gorri | red |

| hals- | *hals | haltza | alder |

| han(n)a | ?*aNane | anaia | brother |

| har-, -ar | *aR | ar | male |

| hars- | *hars | hartz | bear |

| heraus- | *herauś | herauts | boar |

| il(l)un, ilur | *iLun | il(h)un | dark |

| leher | *leheR | leher | pine |

| nescato | *neśka | neska, neskato | girl, young woman |

| ombe, umme | *unbe | ume | child |

| oxson, osson | *otso | otso | wolf |

| sahar | *sahaR | zahar | old |

| sembe | *senbe | seme | son |

| seni | *śeni | sein | boy |

| -ten | *-teN | -ten | diminutive suffix (fossilized) |

| -t(t)o | *-To | -t(t)o | diminutive suffix |

| -x(s)o | *-tso | -txo, -txu | diminutive suffix |

The vascologist Joaquín Gorrochategui, who has written several works on Aquitanian,[8] and Mitxelena have pointed out the similarities of some Iberian onomastic elements with Aquitanian. In particular, Mitxelena spoke about an onomastic pool[9] from which both Aquitanian and Iberian would have drawn:

| Iberian | Aquitanian |

|---|---|

| atin | adin |

| ata | atta |

| baiser | baese-, bais- |

| beleś | belex |

| bels | bels |

| boś | box |

| lauŕ | laur |

| talsku | talsco[10] / HALSCO |

| taŕ | t(h)ar[11] / HAR |

| tautin | tautinn / hauten |

| tetel | tetel[12] |

| uŕke | urcha[12] |

For other more marginal theories see Basque language: Hypotheses on connections with other languages.

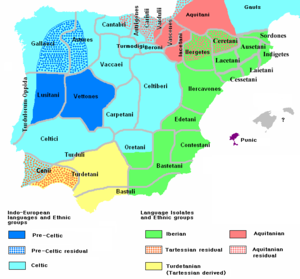

Geographical extent

[edit]

Since ancient times, there have been indications of a relationship between present Southwestern France and the Basques. During the Roman conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar, Aquitania was the territory between the Garonne and the Pyrenees. It was inhabited by tribes of horsemen who Caesar said were very distinct in customs and language from the Celts of Gaul. During the Middle Ages, this territory was named Gascony, derived from Vasconia and cognate with the word Basque.

There are many clues that indicate that Aquitanian was spoken in the Pyrenees at least as far east as Val d'Aran. Placenames that end in ‑os, ‑osse, ‑ons, ‑ost and ‑oz are considered to be of Aquitanian origin, such as the placename Biscarrosse, which is directly related to the city of Biscarrués (note the Navarro-Aragonese phonetic change) south of the Pyrenees. Biscar (modern Basque spelling: bizkar) means "ridge-line". Such suffixes in placenames are ubiquitous in the east of Navarre and in Aragon, with the classical medieval ‑os > ‑ues occurring in stressed syllables, pointing to a language continuum on both sides of the Pyrenees. This strong formal element can be traced on either side of the mountain range as far west as an imaginary line roughly stretching from Pamplona to Bayonne (compare Bardos/Bardoze, Ossès/Ortzaize, Briscous/Beskoitze), where it ceases to appear.

Other than placenames and a little written evidence, the picture is not very clear in the west of the Basque Country, as the historical record is scant. The territory was inhabited by the Caristii, Varduli, and Autrigones, and has been claimed as either Basque or Celtic depending on the author, since Indo-European lexical elements have been found underlying or intertwined in the names given to natural features, such as rivers or mountains (Butrón, Nervión, Deba/Deva, suffix ‑ika etc.) in an otherwise generally Basque linguistic landscape, or Spanish, especially in Álava.

Archaeological findings in Iruña-Veleia in 2006 were initially claimed as evidence of the antiquity of Basque in the south but were subsequently dismissed as a forgery.[13]

The Cantabrians are also mentioned as relatives or allies of the Aquitanians: they sent troops to fight on their side against the Romans.[citation needed]

The Vascones who occupied modern Navarre are usually identified with the Basques (vascos in Spanish), their name being one of the most important pieces of evidence. In 1960, a stele with Aquitanian names was found in Lerga, which could reinforce the idea that Basques and Aquitanians were related. The ethnic and linguistic kinship is confirmed by Julio Caro Baroja, who considers the Aquitanian-Basque relationship an ancient and medieval stage ahead of the well-attested territorial shrinking process undergone by the Basque language during the Modern Age.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Iberian languages

- Gallia Aquitania

- Duchy of Vasconia

- Basque people

- Northern Basque Country

- Vasconic languages

- Neolithic Europe

- Pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula

References

[edit]- ^ See late Basquisation.

- ^ a b Trask, R.L. (1997). The History of Basque. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13116-2.

- ^ Lakarra, Joseba A. (2017). "Basque and the Reconstruction of Isolated Languages". In Campbell, Lyle (ed.). Language Isolates. London: Routledge.

- ^ Datter, Lars. "Basque Onomastics of the Eighth to Sixteenth Centuries - Appendix 4: Names Identified from Roman-Era Aquitanian Stones". larsdatter.com.

- ^ Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society, volumes 52-56 (1942), page 90

- ^ Kelly Lipscomb, Spain (2005), page 457

- ^ S.F. Pushkariova, Primario e secundario en los nombres vascos de los metales, Fontes linguae vasconum: Studia et documenta, vol. 30, no.79 (1998), pp. 417-428.

- ^ Gorrochategui (1984, 1993)

- ^ Michelena (1977), pp. 547–48: "...cada vez soy más escéptico en cuanto a un parentesco lingüístico ibero-vasco. En el terreno de la onomástica, y en particular de la antroponimia, hay, sin embargo, coincidencias innegables entre ibérico y aquitano y, por consiguiente, entre ibérico y vasco. Como ya he señalado en otros lugares, parece haber habido una especie de pool onomástico, del que varias lenguas, desde el aquitano hasta el idioma de las inscripciones hispánicas en escritura meridional, podían tomar componentes de nombre propios."

- ^ Trask (1997), p. 182

- ^ Trask (2008) thinks this could be related to the Basque ethnonym suffix -(t)ar, but this is unlikely because the personal names where it appears (sometimes as the first element, as in Tarbeles) don't look at all like ethnonyms.

- ^ a b For Gorrochategui (1984), the personal name Urchatetelli (#381) is "clearly Iberian."

- ^ Tremlett, Giles (November 24, 2008). "Finds that made Basques proud are fake, say experts". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

Further reading

[edit]- Ballester, Xaverio (2001): "La adfinitas de las lenguas aquitana e ibérica", Palaeohispanica 1, pp. 21–33.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (1984): Onomástica indígena de Aquitania, Bilbao.

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (1993): La onomástica aquitana y su relación con la ibérica, Lengua y cultura en Hispania prerromana : actas del V Coloquio sobre lenguas y culturas de la Península Ibérica : (Colonia 25–28 de Noviembre de 1989) (Francisco Villar and Jürgen Untermann, eds.), ISBN 84-7481-736-6, pp. 609–34

- Gorrochategui, Joaquín (1995): "The Basque Language and its Neighbors in Antiquity", Towards a History of the Basque Language, pp. 31–63.

- Gorrochategui Churruca, Joaquín (2020). "Aquitano Y Vascónico". In: Palaeohispanica: Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua, n.º 20 (noviembre). pp. 721-48. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.405.

- Hoz, Javier de (1995): "El poblamiento antiguo de los Pirineos desde el punto de vista lingüístico", Muntanyes i Població. El passat dels Pirineus des d'una perspectiva multidisciplinària, pp. 271–97.

- Michelena, Luis (1954): "De onomástica aquitana", Pirineos 10, pp. 409–58.

- Michelena, Luis (1977): Fonética histórica vasca, San Sebastián.

- Núñez, Luis (2003): El Euskera arcaico. Extensión y parentescos Archived 2012-02-09 at the Wayback Machine, Tafalla.

- Orduña Aznar, Eduardo (2021). "Onomástica Ibérica Y Vasco-Aquitana: Nuevos Planteamientos". In: Palaeohispanica: Revista Sobre Lenguas Y Culturas De La Hispania Antigua 21 (diciembre). pp. 467-94. https://doi.org/10.36707/palaeohispanica.v21i0.414.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002): "La hipótesis del vascoiberismo desde el punto de vista de la epigrafía íbera", Fontes Linguae Vasconum 90, pp. 197–219.

- Rodríguez Ramos, Jesús (2002): "Índice crítico de formantes de compuesto de tipo onomástico en la lengua íbera", Cypsela 14, pp. 251–75.

- Trask, L.R. (1995): "Origin and relatives of the Basque Language: Review of the evidence", Towards a History of the Basque Language, pp. 65–99.

- Trask, L.R. (1997): The History of Basque, London/New York, ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- Trask, L.R. (2008): "Etymological Dictionary of Basque" (PDF). (edited for web publication by Max Wheeler), University of Sussex

- Velaza, Javier (1995): "Epigrafía y dominios lingüísticos en territorio de los vascones", Roma y el nacimiento de la cultura epigráfica en occidente, pp. 209–18.