Linux Standard Base

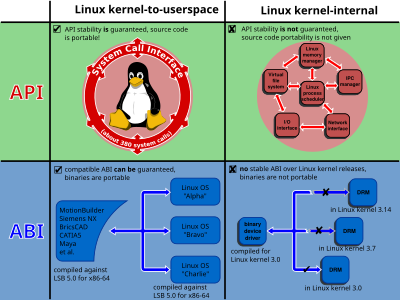

The Linux Standard Base (LSB) was a joint project by several Linux distributions under the organizational structure of the Linux Foundation to standardize the software system structure, including the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard. LSB was based on the POSIX specification, the Single UNIX Specification (SUS), and several other open standards, but extended them in certain areas.

According to LSB:

The goal of the LSB is to develop and promote a set of open standards that will increase compatibility among Linux distributions and enable software applications to run on any compliant system even in binary form. In addition, the LSB will help coordinate efforts to recruit software vendors to port and write products for Linux Operating Systems.

LSB compliance might be certified for a product by a certification procedure.[1]

LSB specified standard libraries (centered around the ld-lsb.so), a number of commands and utilities that extend the POSIX standard, the layout of the file system hierarchy, run levels, the printing system, including spoolers such as CUPS and tools like Foomatic, and several extensions to the X Window System. It also specified boot facilities, such as $local_fs, $network, which were used to indicate service dependencies in System V-style initialization scripts.[2] A machine readable comment block at the top of a script provided the information necessary to determine at which point of the initialization process the script should be invoked; it was called the LSB header.[3]

The command lsb_release -a was available in many systems to get the LSB version details, or could be made available by installing an appropriate package, for example the redhat-lsb package in Red-Hat-flavored distributions such as Fedora,[4] or the lsb-release package in Debian-based distributions.

The standard stopped being updated in 2015 and current Linux distributions do not adhere to or offer it; however, the lsb_release command is sometimes still available.[citation needed] On February 7, 2023, a former maintainer of the LSB wrote, "The LSB project is essentially abandoned."[5]

Backward compatibility

[edit]

LSB was designed to be binary-compatible and produced a stable application binary interface (ABI) for independent software vendors. To achieve backward compatibility, each subsequent version was purely additive. In other words, interfaces were only added; no interfaces were removed. The LSB adopted an interface deprecation policy to give application developers enough time in case an interface was removed from LSB.

This allowed the developer to rely on every interface in LSB for a known time and also to plan for changes. Interfaces were only removed after having been marked "deprecated" for at least three major versions, or roughly eleven years.[6]

LSB 5.0 was the first major release that broke backward compatibility with earlier versions.[7]

Version history

[edit]- 1.0: Initial release June 29, 2001.

- 1.1: Released January 22, 2002. Added hardware-specific specifications (IA-32).

- 1.2: Released June 28, 2002. Added hardware-specific specifications (PowerPC 32-bit). Certification began July 2002.

- 1.2.1: Released October 2002. Added Itanium.

- 1.3: Released December 17, 2002. Added hardware-specific specifications (Itanium, Enterprise System Architecture/390, z/Architecture).

- 2.0: Released August 31, 2004

- LSB is modularized to LSB-Core, LSB-CXX, LSB-Graphics, and LSB-I18n (not released)

- New hardware-specific specifications (PowerPC 64-bit, AMD64)

- Synchronized to Single UNIX Specification (SUS) version 3

- 2.0.1: Released October 21, 2004, ISO version of LSB 2.0, which included specification for all hardware architectures (except LSB-Graphics, of which only a generic version is available).

- 2.1: Released March 11, 2005.

- 3.0: Released July 1, 2005. Among other library changes:

- GNU C Library version 2.3.4

- C++ ABI is changed to the one used by gcc 3.4

- The core specification is updated to ISO POSIX (2003)

- Technical Corrigenda 1: 2005

- 3.1: Released October 31, 2005. This version has been submitted as ISO/IEC 23360:2006.

- 3.2: Released January 28, 2008. This version has been submitted as ISO/IEC 23360:2006.

- 4.0: Released November 11, 2008. This version contains the following features:

- GNU C Library version 2.4

- Binary compatibility with LSB 3.x

- Easier to use SDK

- Support for newer versions of GTK and Cairo graphical libraries

- Java (optional module)

- Simpler ways of creating LSB-compliant RPM packages

- Crypto API (via the Network Security Services library) (optional module)

- 4.1: Released February 16, 2011:[8]

- 5.0: Released June 2, 2015, This version has been submitted as ISO/IEC 23360:2021

- GNU C Library version 2.10 (for psiginfo)

- First major release that breaks backward compatibility with earlier versions (compatible with LSB 3.0, and mostly compatible with LSB 3.1 and later, with some exceptions[10])

- Incorporates the changes made in FHS 3.0

- Qt 3 library has been removed

- Evolved module strategy; LSB is modularized to LSB Core, LSB Desktop, LSB Languages, LSB Imaging, and LSB Trial Use

ISO/IEC standard

[edit]The LSB, version 3.1, is registered as an official ISO/IEC international standard. The main parts of it are:

- ISO/IEC 23360-1:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 1: Generic specification[11]

- ISO/IEC 23360-2:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 2: Specification for IA-32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-3:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 3: Specification for IA-64 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-4:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 4: Specification for AMD64 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-5:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 5: Specification for PPC32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-6:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 6: Specification for PPC64 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-7:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 7: Specification for S390 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-8:2006 Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 — Part 8: Specification for S390X architecture

There is also ISO/IEC TR 24715:2006 which identifies areas of conflict between ISO/IEC 23360 (the Linux Standard Base 3.1 specification) and the ISO/IEC 9945:2003 (POSIX) International Standard.[12]

The LSB, version 5.0, is also registered as an official ISO/IEC international standard.

- ISO/IEC 23360-1-1:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-1: Common definitions

- ISO/IEC 23360-1-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-2: Core specification generic part

- ISO/IEC 23360-1-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-3: Desktop specification generic part

- ISO/IEC 23360-1-4:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-4: Languages specification

- ISO/IEC 23360-1-5:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-5: Imaging specification

- ISO/IEC TS 23360-1-6:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 1-6: Graphics and Gtk3 specification

- ISO/IEC 23360-2-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 2-2: Core specification for X86-32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-2-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 2-3: Desktop specification for X86-32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-3-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 3-2: Core specification for IA64 (Itanium™) architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-3-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 3-3: Desktop specification for IA64 (Itanium TM) architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-4-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 4-2: Core specification for AMD64 (X86-64) architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-4-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 4-3: Desktop specification for AMD64 (X86-64) architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-5-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 5-2: Core specification for PowerPC 32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-5-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 5-3: Desktop specification for PowerPC 32 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-6-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 6-2: Core specification for PowerPC 64 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-6-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 6-3: Desktop specification for PowerPC 64 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-7-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 7-2: Core specification for S390 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-7-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 7-3: Desktop specification for S390 architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-8-2:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 8-2: Core specification for S390X architecture

- ISO/IEC 23360-8-3:2021 Linux Standard Base (LSB) — Part 8-3: Desktop specification for S390X architecture

ISO/IEC 23360 and ISO/IEC TR 24715 can be freely downloaded from ISO website.[13]

Reception

[edit]While LSB was a standard and without a competitor, it was followed only by few Linux distributions. For instance, only 21 distribution releases (versions) were certified for LSB version 4.0, notably Red Flag Linux Desktop 6.0, Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.0, SUSE Linux Enterprise 11, and Ubuntu 9.04 (Jaunty Jackalope);[14] even fewer were certified for version 4.1.

The LSB was criticized[15][16][17][18] for not taking input from projects, most notably the Debian project, outside the sphere of its member companies.

Choice of the RPM package format

[edit]LSB specified that software packages should either be delivered as an LSB-compliant installer,[19] or (preferably) be delivered in a restricted form of the RPM Package Manager format.[20]

This choice of package format precluded the use of other existing package formats not compatible with RPM. To address this, the standard did not dictate which package format the system must use for its own packages, merely that RPM must be supported to allow packages from third-party distributors to be installed on a conforming system.

Limitations on Debian

[edit]Debian included optional support for LSB early on, at version 1.1 in "woody" (3.0; July 19, 2002), 2.0 in "sarge" (3.1; June 6, 2005), 3.1 in "etch" (4.0; April 8, 2007), 3.2 in "lenny" (5.0; February 14, 2009) and 4.1 in "wheezy" (7; May 4, 2013). To use foreign LSB-compliant RPM packages, the end-user needs to use Debian's Alien program to transform them into the native package format and then install them.

The LSB-specified RPM format had a restricted subset of RPM features—to block usage of RPM features that would be untranslatable to .deb with Alien or other package conversion programs, and vice versa, as each format has capabilities the other lacks. In practice, not all Linux binary packages were necessarily LSB-compliant, so while most could be converted between .rpm and .deb, this operation was restricted to a subset of packages.

By using Alien, Debian was LSB-compatible for all intents and purposes, but according to the description of their lsb package,[21] the presence of the package "does not imply that we believe that Debian fully complies with the Linux Standard Base, and should not be construed as a statement that Debian is LSB-compliant."[21]

Debian strived to comply with the LSB, but with many limitations.[22] However, this effort ceased around July 2015 due to lack of interest and workforce inside the project.[23] In September 2015, the Debian project confirmed that while support for Filesystem Hierarchy Standard (FHS) would continue, support for LSB had been dropped.[24] Ubuntu followed Debian in November 2015.[25]

Quality of compliance test suites

[edit]Additionally, the compliance test suites were criticized for being buggy and incomplete—most notably, in 2005 Ulrich Drepper criticized the LSB for poorly written tests which can cause incompatibility between LSB-certified distributions when some implement incorrect behavior to make buggy tests work, while others apply for and receive waivers from complying with the tests.[26] He also denounced a lack of application testing, pointing out that testing only distributions can never solve the problem of applications relying on implementation-defined behavior.[26]

For the vendors considering LSB certifications in their portability efforts, the Linux Foundation sponsored a tool that analyzed and provided guidance on symbols and libraries that go beyond the LSB.[27]

See also

[edit]- Intel Binary Compatibility Standard (iBCS)

- POSIX (Portable Operating System Interface)

References

[edit]- ^ "Certifying an Application to the LSB". Linux Foundation. 2008. Archived from the original on July 15, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Facility Names". Linux Standard Base Core Specification 3.1. 2005.

- ^ "Comment conventions for init scripts". Linux Standard Base Core Specification 3.1. 2005.

- ^ "Package redhat-lsb". fedoraproject.org. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "Re: Archive of this Mailing List". lsb-discuss mailing list. February 7, 2023.

- ^ "LSB Roadmap". Linux Foundation. 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "LSB 5.0 Release Notes". linuxfoundation.org. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ djwm (March 10, 2011). "Java removed from Linux Standard Base 4.1". Archived from the original on December 7, 2013.

- ^ "Java removed from Linux Standard Base 4.1". h-online.com. March 10, 2011. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- ^ "LSB 5.0 Release Notes: Qt 3 Removed". linuxfoundation.org. Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- ^ ISO/IEC 23360-1:2006 - Linux Standard Base (LSB) core specification 3.1 -- Part 1: Generic specification. Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ ISO/IEC TR 24715:2006 - Information technology -- Programming languages, their environments and system software interfaces -- Technical Report on the Conflicts between the ISO/IEC 9945 (POSIX) and the Linux Standard Base (ISO/IEC 23360). Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ "ISO Publicly Available Standards". Retrieved October 15, 2011.

- ^ Certified Products Product Directory on linuxbase.org (2015-01-12)

- ^ "bugs.debian.org".

- ^ "linuxfoundation.org".[permanent dead link]

- ^ "openacs.org".

- ^ "osnews.com".

- ^ "Chapter 22. Software Installation 22.1. Introduction". Linux Standard Base Core Specification 3.1. 2005.

- ^ "Chapter 22. Software Installation 22.3. Package Script Restrictions". Linux Standard Base Core Specification 3.1. 2005.

- ^ a b "Debian -- Details of package lsb in lenny (stable) -- Linux Standard Base 3.2 support package". Debian Project. August 18, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Debian LSB". Debian Project. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "Debian LSB ML discussion". Debian Project. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- ^ "Debian dropping the Linux Standard Base". LWN.net.

- ^ "lsb 9.20150917ubuntu1 source package in Ubuntu". November 19, 2015.

- ^ a b Drepper, Ulrich (September 17, 2005). "Do you still think the LSB has some value?". Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ "All About the Linux Application Checker". Linux Foundation. 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

External links

[edit]- Linux Standard Base Specifications Archive, linuxfoundation.org

- Linux Standard Base (LSB), wiki.linuxfoundation.org

- Open Linux VERification (OLVER) Project, linuxtesting.org

- search for lsb packages, pkgs.org

- lsb, pkgs.org

- lsb in Launchpad, launchpad.net - bug reports

Media:

- Additional Vendors Participate in Growing LSB Effort, 1998, debian.org - describes the breakdown of teams (at the time) and who was involved, of historical interest

- Four Linux Vendors Agree On An LSB Implementation, 2004, slashdot.org

- Yes, the LSB Has Value, 2005, licquia.org – response to Drepper by Jeff Licquia