Music of Hungary

| Music of Hungary | ||||||

| Genres | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media and performance | ||||||

|

||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||

|

||||||

Hungary has made many contributions to the fields of folk, popular and classical music. Hungarian folk music is a prominent part of the national identity and continues to play a major part in Hungarian music.[1][2] The Busójárás carnival in Mohács is a major folk music event in Hungary, formerly featuring the long-established and well-regarded Bogyiszló orchestra.[3] Instruments traditionally used in Hungarian folk music include the citera, cimbalom, cobza, doromb, duda, kanászkürt, tárogató, tambura, tekero and ütőgardon. Traditional Hungarian music has been found to bear resemblances to the musical traditions of neighbouring Balkan countries and Central Asia.[4][5]

Hungarian classical music has long been an "experiment, made from Hungarian antedecents and on Hungarian soil, to create a conscious [variant of] musical culture [using the] musical world of the folk song".[6] Although the Hungarian upper class has long had cultural and political connections with the rest of Europe, leading to an influx of European musical ideas, the rural peasants maintained their own traditions such that by the end of the 19th century, Hungarian composers could draw on rural peasant music to (re)create a Hungarian classical style.[7] For example, Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály, two of Hungary's most famous composers, are known for using folk themes in their music. Bartók collected folk songs from across Central and Eastern Europe, including Croatia, Czechia, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Serbia, whilst Kodály was more interested in uncovering a distinctively Hungarian musical style.

One of the most significant musical genres in Hungary is Romani music, with a historical presence dating back many centuries. Hungarian Romani music is an integral part of the national culture, and it has become increasingly popular throughout the country.[8]

During the era of Communist rule in Hungary (1949–1989) a Song Committee scoured and censored popular music for traces of subversion and ideological impurity. Since then, however, the Hungarian music industry has begun to recover, producing successful performers in the fields of jazz such as trumpeter Rudolf Tomsits, pianist-composer Károly Binder and, in a modernized form of Hungarian folk, Ferenc Sebő and Márta Sebestyén. The three giants of Hungarian rock, Illés, Metró and Omega, remain very popular.

Characteristics

[edit]

Unlike most European peoples, the Hungarian people, Magyars, emerged from the intermingling of Ugric and Eastern Turkic peoples during the fifth to eighth centuries AD.[7] This makes the origins of their traditional music unique in Europe. According to author Simon Broughton, the composer and song collector Kodály identified songs that "apparently date back 2,500 years" in common with the Mari people of Russia;[9] and, as well as the Mari, the ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl indicates similarities in traditional Hungarian music with Mongolian and Native American musical styles.[10] Bence Szabolcsi, however, claims that the Finno-Ugric and Turkish-Mongolian elements are present but "cannot be attached to certain, definite national or linguistic groups". Nonetheless, Szabolcsi claims links between Hungarian musical traditions and those of the Mari, Kalmyk, Ostyak, northwest Chinese, Tatar, Vogul, Anatolian Turkish, Bashkirian, Mongol and Chuvash musics. These, he claims, are evidence that "Asian memories slumber in the depths of Hungarian folk music and that this folk music is the last Western link in the chain of ancient Eastern cultural relations".[7]

According to Broughton, traditional Hungarian music is "highly distinctive" like the Hungarian language, which invariably is stressed on the first syllable, lending a strongly accented dactylic rhythm to the music".[3] Nettl identifies two "essential features" of Hungarian folk music to be the use of "pentatonic scales composed of major seconds and minor thirds" (or "gapped scales"[10]) and "the practice of transposing a bit of melody several times to create the essence of a song". These transpositions are "usually up or down a fifth", a fundamental interval in the series of overtones and an indication perhaps of the "influence of Chinese musical theory in which the fifth is significant".[10]

According to Szabolcsi, these 'Hungarian transpositions', along with "some melodic, rhythmical and ornamental peculiarities, clearly show on the map of Eurasia the movements of Turkish people from the East to the West".[7] The subsequent influence on neighbouring countries' music is seen in the music of Slovakia, Poland, and, with intervals of the third or second, in the music of the Czech Republic. Hungarian and Finnoic musical traditions are also characterised by the use of an ABBA binary musical form, with Hungary itself especially known for the A A' A' A variant, where the B sections are the A sections transposed up or down a fifth (A').[10] Modern Hungarian folk music evolved in the 19th century, and is contrasted with previous styles through the use of arched melodic lines as opposed to the more archaic descending lines.[11]

Music history

[edit]

The earliest documentation of Hungarian music dates from the introduction of Gregorian chant in the 11th century. By that time, Hungary had begun to enter the European cultural establishment with the country's conversion to Christianity and the musically important importation of plainsong, a form of Christian chant. Though Hungary's early religious musical history is relatively well documented, secular music remains mostly unknown, though it was apparently a common feature of community festivals and other events.[11] The earliest documented instrumentation in Hungary dates back to the whistle in 1222, the Koboz around 1237-1325,[12] the bugle in 1355, the fiddle in 1358, the bagpipe in 1402, the lute in 1427 and the trumpet in 1428. Thereafter the organ came to play a major role.[7]

The 16th century saw the rise of Transylvania as a centre for Hungarian music. It also saw the first publication of music in Hungary, in Kraków. At this time Hungarian instrumental music was well known in Europe; the lutenist and composer Bálint Bakfark, for example, was famed as a virtuoso player. His compositions pioneered a new style of writing for the lute based on vocal polyphony. The lutenist brothers Melchior and Konrad Neusiedler were also noted, as was Stephan Monetarius, the author of an important early work in music theory, the Epithoma utriusque musices.[7]

During the 16th century, Hungary was divided into three parts: an area controlled by the Turks; an Ottoman vassal state (the Principality of Transylvania); and an area controlled by the Habsburgs. Historic songs declined in popularity and were replaced by lyrical poetry, whilst minstrels were replaced by court musicians. Many courts or households maintained large ensembles of musicians who played the trumpet, whistle, cimbalom, violin or bagpipes. Some of these ensemble musicians were German, Polish, French or Italian; the court of Gábor Bethlen, Prince of Transylvania, included a Spanish guitarist. Little detail about the music played during this era survives, however.[7] Musical life in the areas controlled by the Ottoman Turks declined precipitously, with even the formerly widespread and entrenched plainsong style disappearing by the end of the 17th century. Outside of the Ottoman area, however, plainsong flourished after the establishment of Protestant missions in around 1540, while a similarly styled form of folk song called verse chronicles also arose.[11]

During the 18th century, some of the students at colleges such as those in Sárospatak and Székelyudvarhely were minor nobles from rural areas who brought with them their regional styles of music. Whilst the choirs in these colleges adopted a more polyphonic style, the students' songbooks indicate a growth in the popularity of homophonic songs. Their notation, however, was relatively crude and no extensive collection appeared until the publication of Ádám Pálóczi Horváth’s Ötödfélszáz Énekek in 1853. These songs indicate that during the mid to late 18th century the previous Hungarian song styles died out and musicians looked more to other (Western) European styles for influence.

The 18th century also saw the rise of verbunkos, a form of music initially used by army recruiters. Like much Hungarian music of the time, melody was treated as more important than lyrics, although this balance changed as verbunkos became more established.[7]

Folk music

[edit]Hungarian folk music changed greatly beginning in the 19th century, evolving into a new style that had little in common with the music that came before it. Modern Hungarian music was characterised by an "arched melodic line, strict composition, long phrases and extended register", in contrast to the older styles which always utilize a "descending melodic line".[11]

Modern Hungarian folk music was first recorded in 1895 by Béla Vikár, setting the stage for the pioneering work of Béla Bartók, Zoltán Kodály and László Lajtha in musicological collecting. Modern Hungarian folk music began its history with the Habsburg Empire in the 18th century, when central European influences became paramount, including a "regular metric structure for dancing and marching instead of the free speech rhythms of the old style. Folk music at that time consisting of village bagpipers who were replaced by string-based orchestras of the Gypsy, or Roma people.[3]

In the 19th century, Roma orchestras became very well known throughout Europe, and were frequently thought of as the primary musical heritage of Hungary, as in Franz Liszt's Hungarian Dances and Rhapsodies, which used Hungarian Roma music as representative of Hungarian folk music[13] Hungarian Romani music is often represented as the only music of the Roma, though multiple forms of Roma music are common throughout Europe and are often dissimilar to Hungarian forms. In the Hungarian language, 19th-century folk styles like the csardas and the verbunkos, are collectively referred to as cigányzene, which translates literally as Gypsy music.[14]

Hungarian nationalist composers, like Bartók, rejected the conflation of Hungarian and Roma music, studying the rural peasant songs of Hungary which, according to music historian Bruno Nettl, "has little in common with" Roma music,[10] a position that is held to by some modern writers, such as the Hungarian author Bálint Sárosi.[14] Simon Broughton, however, has claimed that Roma music is "no less Hungarian and... has more in common with peasant music than the folklorists like to admit",[3] and authors Marian Cotton and Adelaide Bradburn claimed that Hungarian-Roma music was "perhaps... originally Hungarian in character, but (the Roma have made so many changes that) it is difficult to tell what is Hungarian and what is" the authentic music of the Roma.[15]

The ethnic Csángó Hungarians of Moldavia's Seret Valley have moved in large numbers to Budapest, and become a staple of the local folk scene with their distinctive instrumentation using flutes, fiddles, drums and the lute.[3]

Prominent folk ensembles, such as the Hungaria Folk Orchestra, the Danube Folk Ensemble and the Hungarian State Folk Ensemble have regular performances in Budapest and are a popular attraction for visitors.

Verbunkos

[edit]

In the 19th century, verbunkos was the most popular style in Hungary. This consisted of a slow dance followed by a faster dance; this dichotomy, between the slower and faster dances, has been seen as the "two contrasting aspects of the Hungarian character".[3] The rhythmic patterns and embellishments of the verbunkos are distinctively Hungarian in nature, and draw heavily upon the folk music composed in the early part of the century by Antal Csermak, Ferdinand Kauer, Janos Lavotta and others.[11]

Verbunkos was originally played at recruitment ceremonies to convince young men to join the army, and was performed, as in so much of Hungarian music, by Roma bands. One verbunkos tune, the "Rákóczi March" became a march that was a prominent part of compositions by both Liszt and Hector Berlioz. The 18th-century origins of verbunkos are not well known, but probably include old dances like the swine-herd dance and the Hajduk dance, as well as elements of Balkan, Slavic and Levantine music, and the cultured music of Italy and Vienna, all filtered through the Roma performers. Verbunkos became wildly popular, not just among the poor peasantry, but also among the upper-class aristocratics, who saw verbunkos as the authentic music of the Hungarian nation. Characteristics of verbunkos include the bokázó (clicking of heels) cadence-pattern, the use of the interval of the augmented second, garlands of triplets, widely arched, free melodies without words, and alternately swift and slow tempi. By the end of the 18th century, verbunkos was in use in opera, chamber and piano music, and in song literature, and was regarded as "the continuation, the resurrection of ancient Hungarian dance and music, and its success signified the triumph of the people's art".[7]

The violinist Panna Czinka was among the most celebrated musicians of the 19th century, as was the Roma bandleader János Bihari, known as the "Napoleon of the fiddle".[3] Bihari, Antal Csermák and other composers helped make verbunkos the "most important expression of the Hungarian musical Romanticism" and have it "the role of national music". Bihari was especially important in popularizing and innovating the verbunkos; he was the "incarnation of the musical demon of fiery imagination".[16] Bihari and others after his death helped invent nóta, a popular form written by composers like Lóránd Fráter, Árpád Balázs, Pista Dankó, Béni Egressy, Márk Rózsavölgyi and Imre Farkas.[17] Many of the biggest names in modern Hungarian music are the verbunkos-playing Lakatos family, including Sándor Lakatos and Roby Lakatos.[3]

Roma music

[edit]Though the Roma are primarily known as the performers of Hungarian styles like verbunkos, they have their own form of folk music that is largely without instrumentation, in spite of their reputation in that field outside of the Roma community. Roma music tends to take on characteristics of whatever music the people are around, however, embellished with "twists and turns, trills and runs", making a very new, and distinctively Roma style. Though without instruments, Roma folk musicians use sticks, tapped on the ground, rhythmic grunts and a technique called oral-bassing which vocally imitates the sound of instruments. Some modern Roma musicians, like Ando Drom, Romano Drom, Romani Rota and Kalyi Jag have added modern instruments like guitars to the Roma style, while Gyula Babos' Project Romani has used elements of avant-garde jazz.[3]

Hungarian music abroad

[edit]Ethnic Hungarians live in parts of the Czech Republic, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Serbia, Slovenia, and elsewhere. Of these, the Hungarian population of Romania (both in the region of Transylvania and among the Csángó people) - being the more rural, outer rims of the kingdom of Hungary - has had the most musical impact on Hungarian folk music. The Hungarian community in Slovakia has produced the roots revival band Ghymes, who play in the táncház tradition.[18] The Serbian region of Vojvodina is home to a large Hungarian minority

Transylvanian folk music remains vital part of life in modern Transylvania. Bartók and Kodály found Transylvania to be a fertile area for folk song collecting. Folk bands are usually a string trio, consisting of a violin, viola and double bass, occasionally with a cimbalom; the first violin, or primás, plays the melody, with the others accompanying and providing the rhythm.[3] Transylvania is also the original home of the táncház tradition, which has since spread throughout Hungary.

Táncház

[edit]Táncház (literally "dance house") is a dance music movement which first appeared in the 1970s as a reaction against state-supported homogenised and sanitised folk music. They have been described as a "cross between a barn dance and folk club", and generally begin with a slow tempo verbunkos (recruiting dance), followed by swifter csárdás dances. Csárdás is a very popular Hungarian folk dance that comes in many regional varieties, and is characterized by changes in tempo. Táncház began with the folk song collecting of musicians like Béla Halmos and Ferenc Sebő, who collected rural instrumental and dance music for popular, urban consumption, along with the dance collectors György Martin and Sándor Timár. The most important rural source of these songs was Transylvania, which is actually in Romania but has a large ethnic Hungarian minority. The instrumentation of these bands, based on Transylvanian and sometimes the southern Slovak Hungarian communities, included a fiddle on lead with violin, a kontra (a 3-string viola also called a brácsa), and bowed double bass, and sometimes a cimbalom as well.[3]

Many of the biggest names in modern Hungarian music emerged from the táncház scene, including Muzsikás and Márta Sebestyén. Other bands include Vujicsics, Jánosi, Téka and Kalamajka, while singers include Éva Fábián and András Berecz. Famous instrumentalists include fiddlers Csaba Ökrös and Balázs Vizeli, cimbalomist Kálmán Balogh, violinist Félix Lajkó (from Subotica in Serbia) and multi-instrumentalist Mihály Dresch.[3]

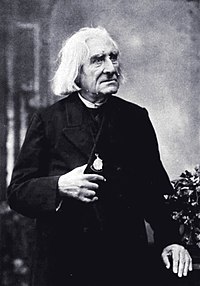

Classical music

[edit]Hungary's most important contribution to the worldwide field of European classical music is probably Franz Liszt,[15] a renowned pianist in his own time and a well-regarded composer of 19 Hungarian Rhapsodies and a number of symphonic poems such as Les préludes. Liszt was among the major composers during the late 19th century, a time when modern Hungarian classical music was in its formative stage. Along with Liszt and his French Romantic tendencies, Ferenc Erkel's Italian and French-style operas, with Hungarian words, and Mihály Mosonyi's German classical style, helped set the stage for future music, and their influence is "unsurpassed even by their successors, because in addition to their individual abilities they bring about an unprecedented artistic intensification of the Romantic musical idiom, which is practically consumed by this extreme passion".[19] Elements of Hungarian folk music, especially verbunkos, became important elements of many composers, both Hungarians like Kalman Simonffy and foreign composers like Johannes Brahms and Ludwig van Beethoven.[11]

Hungary has also produced Karl Goldmark, composer of the Rustic Wedding Symphony, composer and pianist Ernő Dohnányi, composer and ethnomusicologist László Lajtha, and the piano composer Stephen Heller. A number of violinists from Hungary have also achieved international renown, especially Joseph Joachim, Tivadar Nachéz, Jenő Hubay, Edward Reményi, Sándor Végh, Franz von Vecsey, Ede Zathureczky, Emil Telmányi, Tibor Varga and Leopold Auer. Hungarian-born conductors include Antal Doráti; ; Eugene Ormandy; Fritz Reiner; George Szell and Georg Solti, Ádám Fischer and Iván Fischer, as well as Gregory Vajda.[15] Pianists of international renown: Géza Anda, Tamás Vásáry, Georges Cziffra, Annie Fischer, Zoltán Kocsis, Dezső Ránki, András Schiff and Jenő Jandó

Hungarian opera

[edit]The origins of Hungarian opera can be traced to the late 18th century, with the rise of imported opera and other concert styles in cities like Pozsony, Kismarton, Nagyszeben and Budapest. Operas at the time were in either the German or Italian style. The field Hungarian opera began with school dramas and interpolations of German operas, which began at the end of the 18th century. School dramas in places like the Pauline School in Sátoraljaújhely, the Calvinist School in Csurgó and the Piarist School in Beszterce.[3]

Pozsony produced the first music drama experiments in the country, though the work of Gáspár Pacha and József Chudy; it was the latter's 1793 Prince Pikkó and Jutka Perzsi that is generally considered the first opera in a distinctively Hungarian style. The text of that piece was translated from Prinz Schnudi und Prinzessin Evakathel by Philipp Hafner. This style was still strongly informed by the Viennese Zauberposse style of comedic play, and remained thus throughout the 19th century. Though these operas used foreign styles, the "idyllic, lyric and heroic" parts of the story were always based on verbunkos, which was becoming a symbol of the Hungarian nation during this time.[3] It was not until the middle of the 19th century that Ferenc Erkel wrote the first Hungarian language opera, using French and Italian models, thus launching the field of Hungarian opera.[17]

Bartók and Kodály

[edit]At the end of the 19th century, Hungarian music was dominated by compositions in the German classical style, while Viennese-style operettas gained immensely in popularity. This ended beginning in about 1905, when Endre Ady's poems were published, composer Béla Bartók was published for the first time, and Zoltán Kodály began collecting folk songs. Bartók and Kodály were two exceptional composers who created a distinctively Hungarian style. Bartók collected songs across Eastern Europe, though much of his activity was in Hungary, and he used their elements in his music. He was interested in all forms of folk music, while Kodály was more specifically Hungarian in his outlook. In contrast to previous composers who worked with Hungarian popular musical idioms, Kodály and Bartók drew a sharp line between the popular music played by Roma (also known as "magyarnóta", or Hungarian music or Gypsy music) and the music of farmers.[20] Their work was a watershed that incorporated "every great tradition of the Hungarian people" and influenced all the later composers of the country.[21]

Later 20th century

[edit]For the first half of the 20th century, Bartók and Kodály were potent symbols for a generation of composers, especially Kodály. Starting in about 1947, a revival in folk choir music began, ended as an honest force by 1950, when state-run art became dominant with the rise of Communism. Under Communism, "(c)ommitment and ideological affiliation (were) measured by the musical style of a composer; the ignominious adjectives 'formalistic' and 'cosmopolitan' gain currency ... (and the proper Hungarian style was) identified with the major mode, the classical aria, rondo or sonata form, the chord sequences distilled" from Kodály's works. Music was uniformly festive and optimistic, with every deviation arousing suspicion; this simplicity led to a lack of popular support from the public, who did not identify with the sterile approved styles. The most prominent composers of this period were Endre Szervánszky, Ferenc Szabó and Lajos Bárdos.[22]

Beginning in about 1955, a new wave of composers appeared, inspired by Bartók and breathing new life into Hungarian music. Composers from this era included András Mihály,[23] Endre Szervánszky, Pál Kadosa, Ferenc Farkas and György Ránki. These composers both brought back old techniques of Hungarian music, as well as adapting imported avant-garde and modernist elements of Western classical music.[24] György Ligeti and György Kurtág are often mentioned in the same sentence. They were born near each other in Transylvania and studied in Budapest in the 1940s. Both were influenced by Stockhausen. Kurtág's modernism borrowed many influences from the past. By contrast Ligeti invented a new language with chromatic tone clusters and elements of parody. Both were multi-lingual and became exiles. This is reflected in the texts for their works. The foundation of the New Music Studio in 1970 helped further modernise Hungarian classical music though promoting composers that felt audience education was as important a consideration as artistic merit in composition and performance; these Studio's well-known composers include László Vidovszky, László Sáry and Zoltán Jeney.[11] Miklós Rózsa, who studied in Germany and eventually settled in the United States, achieved international recognition for his Hollywood film scores as well as his concert music.

Popular music

[edit]Hungarian popular music in the early 20th century consisted of light operettas and the Roma music of various styles. Nagymező utca, the "Broadway of Budapest", was a major centre for popular music, and boasted enough nightclubs and theatres to earn its nickname. In 1945, however, this era abruptly ended and popular music was mostly synonymous with the patriotic songs imposed by the Russian Communists. Some operettas were still performed, though infrequently, and any music with Western influences was seen as harmful and dangerous.[18] In 1956, however, liberalisation began with the "three Ts" ("tiltás, tűrés, támogatás", meaning "prohibition, toleration, support"), and a long period of cultural struggle began, starting with a battle over African American jazz.[18] Jazz became a part of Hungarian music in the early 20th century, and although common place in Budapest's venues such as the Tabarin, the Astoria and Central Cafe which set up its own coffee jazz band,[25] it has not achieved widespread renown until the 1970s, when Hungary began producing internationally known performers like the Benkó Dixieland Band and Béla Szakcsi Lakatos.[11] Other renowned performers from the younger generation are the Hot Jazz Band and the Bohém Ragtime Jazz Band.

Rock

[edit]In the early 1960s, Hungarian youths began listening to rock in droves, in spite of condemnation from the authorities. Three bands dominated the scene by the beginning of the 1970s, Illés, Metró and Omega, all three of which had released at least one album. A few other bands recorded a few singles, but the Record-Producing Company, a state-run record label, did not promote or support these bands, which quickly disappeared.[26]

In 1968, the New Economic Mechanism was introduced, intending on revitalising the Hungarian economy, while the band Illés won almost every prize at the prestigious Táncdalfesztivál. In the 1970s, however, the hard-liners of the Communist party cracked down on dissidence in Hungary, and rock was a major target. The band Illés was banned from performing and recording, while Metró and Omega left. Some of the members of these bands formed a supergroup, Locomotiv GT, that quickly became very famous. The remaining members of Omega, meanwhile, succeeded in achieving stardom in Germany, and remained very popular for a time.[26]

Rock bands in the late 1970s had to conform to the Record Company's demands and ensure that all songs passed the inspection of the Song Committee, who scoured all songs looking for hidden political messages. LGT was the most prominent band of a classic rock style that was very popular, along with Illés, Bergendy and Zorán, while there were other bands like The Sweet and Middle of the Road who catered to the desires of the Song Committee, producing rock-based pop music without a hint of subversion. Meanwhile, the disco style of electronic music produced such performers as the expensively produced and managed Neoton Familia, Beatrice and Szűcs Judit, while the more critically acclaimed progressive rock scene produced bands like East, V73, Color and Panta Rhei.[26]

In the early 1980s, economic depression wracked Hungary, leading to a wave of politically disillusioned and alienated yet vibrant youth culture, a crucial part of which were hard rock, punk, new wave and art rock. Major bands from this era included Beatrice, who had moved from disco to punk and folk-influenced rock and were known for their splashy, uncensored and theatrical performances, P. Mobil, Bikini, Hobo Blues Band, A. E. Bizottság, Európa Kiadó, Sziámi and Edda művek.[26] The first major prison sentences for rock-related subversion were given out, with the members of the punk band CPg sentenced to two years for political incitement.[26][27]

As the communist system was falling apart, the Hungarian Record Company (MHV) was privatized and smaller independent labels such as Bahia and Human Telex were formed. Major multinational companies such as EMI established headquarters in Budapest. Hungarian popular music became incorporated into the global music industry.[28]

Electronic music

[edit]Clubbing and electronic dance music started gaining popularity in Hungary following the change of regime in 1989[29] and corresponding to Electronic music's increasing popularity in the worldwide musical mainstream. The political freedom and cultural boom of western culture opened the way for the clubbing scene, with several venues starting all around the country, especially in Budapest and around Lake Balaton.

The 1990s also marked the creation of several dance formations, notably Soho Party, Splash, Náksi & Brunner and also rave formations such as Emergency House and Kozmix.[30] Notable techno and house DJ-s are Sterbinszky, Budai, and Newl. The workings of the scene culminated in events like Budapest Parade, the largest such street festival in Hungary, that was held yearly from 2000 to 2006, attracting more than half million visitors.[31] The history of Electronic Dance Music and Techno culture in Hungary is documented in Ferenc Kömlődy's book "Fénykatedrális", (1999 in Hungarian).

A thriving underground scene was marked by the start of Tilos Rádió in 1991, the first free independent community station, starting out as a pirate radio. The station soon developed strong ties with the first alternative electronic formations, and inspired to start many others.[32] Bands like Korai Öröm and Másfél (also check Myster Mobius) started, playing ambient, psychedelic music. Anima Sound System, one of the most influential bands on the scene, was created in 1993 playing dub and trip-hop influenced by acid jazz and ethnic music.[33] Several other bands and formations followed, like Colorstar and Neo. Neo has won a worldwide reputation for their unique electro-pop style and the "Mozart of pop music" award (Cannes, 2004) they received for their soundtrack album called "Control". Apart from Anima, ethnic and folk influenced the scene in many ways, exemplified by formations like Balkan Fanatik, or Mitsoura. One of the most successful Hungarian electronic musician is Yonderboi, who recently co-created Žagar, gaining wide reputation in the country. In the past few years, dubstep has gained popular attention as well, nationwide.

Experimental and minimal scene is in its early age, although several crews and DJs are working, organising numerous events. Notable performers include c0p, Cadik, Ferenc Vaspöeri and Isu.

Hip hop

[edit]Hip hop and rap have been developing in Hungary with two scenes, underground and mainstream, which is mostly popular among young people in Hungary. Underground rappers condemn the mainstream for "selling" their music and usually provide deeper message. Mainstream hip hop is dominated by the pioneer of Gangsta rap in Hungary, Ganxsta Zolee, and there are also other famous ones including FankaDeli, Sub Bass Monster, Dope Man, and LL Junior. Mainstream hip-hop is extremely popular among the Romani youth.

Bëlga started as an offshoot hiphop project at Tilos Rádió. As lyrical innovators and phenomenal parodists, they gained wide popularity for an extremely explicit criticism of Budapest public transport company BKV, as well as hilarious wordplays and self-irony. Their lyrics are significant beyond the hip-hop scope as a cultural documentation of turn-of-the-millennia Culture of Hungary.[34]

Hungarian Slam sessions are rare and few, and still a novelty for the mainstream, but are gaining popularity with literary performers, emcees and audiences alike.[35]

Hardcore, metal

[edit]Despite being unknown among most Hungarian people, hardcore and metal are flourishing styles of music in Hungary. Metal bands are formed all over the country. Dominant styles are death metal, black metal and thrash. There are also power metal, folk metal and heavy metal groups, including Dalriada and Thy Catafalque.

Hardcore and metalcore are most common in Budapest and Western Hungary, in towns like Győr, Csorna, Szombathely and Veszprém, but Eastern Hungary and Debrecen is getting into a more and more important place in the hardcore scene. The first Hungarian acts that tagged themselves Hardcore like AMD, Leukémia, Marina revue emerged in the late 1980s, and were followed by a number of acts, constituting a scene that flourishes since the early 1990s.[36] Notable bands were Dawncore and Newborn of the late 1990s gaining also some international success. Members of these bands went on to form Bridge to Solace and The Idoru. Other important, active bands: Hold X True, Fallenintoashes, Embers, Suicide Pride, Subscribe, Road, Shell Beach, Hatred Solution, Blind Myself, Superbutt, Stillborn (Hatebreed tribute). An internationally known band is Ektomorf, infusing heavy ethnic content with harsh vocals,[37] One of North America's most popular metal band with record sales over two million albums; Five Finger Death Punch was formed by the Hungarian born, Golden God Shredder Award winning guitarist Zoltan Bathory

Extreme hardcorepunk and grindcore bands from Hungary include Jack (crustgrind), Human Error(crustcore), Step On It (allschool hardcore), Another Way (fastcore), Gyalázat (crustpunk).

Indie

[edit]The origins of the Hungarian indie music scene go back to the early 1980s when Európa Kiadó, Sziami and Balaton released their records. The first revival took place in the mid-1990s when bands like Sexepil gained international success, followed by Heaven Street Seven. The second and most notable revival of the indie-alternative scene took place in the mid-2000s when bands like Amber Smith, The Moog signed to international labels. Other notable bands include EZ Basic, The KOLIN and Dawnstar. The Hungarian indie scene is closely intertwined with electronic music therefore artists like Yonderboi and Žagar are often considered part of the indie scene.

The Hungarian indie music has its special, Hungarian languaged line. It is based rather on 1980s bands like Európa Kiadó or Neurotic. The most notable bands and artists are Kispál és a borz (the lead singer and songwriter András Lovasi was honored by the Kossuth Prize[38]), Hiperkarma (Róbert Bérczesi made alone the first album), and Quimby (most notable member is Tibor Kiss).

Punk

[edit]The origins of the Hungarian punk movement go back to the early eighties, when a handful of bands like ETA, QSS, CPG, and Auróra emerged as angry young men playing fast and raw punk rock music. Like many other musicians of their age, they often criticised the communist government. They were a part of the national movement to reject the oppressiveness, and particularly the censorship, of the communist regime. As their music was on the verge of acceptance both by the public and the authorities, concerts were held under tight police control, and often caused moral outrage. With band members often living under constant surveillance, prison was a serious possibility. Two members of the band CPG were found guilty and sent to prison for two years for allegedly unmoral lyrics. After their release, they had to leave Hungary, as did Auróra’s lead singer.

The change of regime in 1989 brought a new situation, and bands now revolted against corruption and the Americanisation of the country. They felt that the new system retained the bad things from the previous one, but lacked that good things that many expected. In lyrics, they often mention the newly appearing organised crime, and the still low standard of living.

Today the Hungarian punk scene is low profile, but vibrant with several active bands, often touring the country and beyond. Summer brings a slew of punk and alternative festivals where they can all be sampled. Top venues playing punk music around Budapest include Vörös Yuk, Borgödör, Music Factory and A38 Hajó.

Major bands include Auróra, the oldest Hungarian punk band with twenty-five years of history, come from the northwest Hungarian town of Győr and their originally street punk music has been recently updated with a ska-punk flavor, HétköznaPI CSAlódások (also called PICSA), a simplistic but powerful punk band, most popular in the end of the 1990s. They, similarly to Junkies, Fürgerókalábak, and Prosectura, are part of the new wave of punk bands that had risen in the mid-late 1990s in Hungary. Out of the newer bands, two northeast Hungarian bands are the most known, both playing California punk: Alvin és a mókusok come from Nyíregyháza, while Macskanadrág are from Salgótarján.

Festivals, venues and other institutions

[edit]Folk and classical music

[edit]Budapest, the capital and music centre of Hungary,[15] is one of the best places to go in Hungary to hear "really good folk music", says world music author Simon Broughton. The city is home to an annual folk festival called Táncháztalálkozó ("Meeting of the Táncházak", literally "dance houses"), which is a major part of the modern music scene.[3] The Budapest Spring Festival along with the Budapest Autumn Festival are large scale cultural events every year. The Budapesti Fesztivál Zenekar[39] (Budapest Festival Orchestra) has recently been awarded the Editor's Choice Gramophone Award.[40] Long-standing venues in Budapest include the Philharmonic Society (founded 1853), the Opera House of Budapest (founded 1884) the Academy of Music, which opened in 1875 with President Franz Liszt and Director Ferenc Erkel and which has remained the centre for music education in the country since.[7]

Popular music festivals

[edit]

Several musical festivals have been launched since the early 1990s propelled by increasing demand of the developing youth culture. Aside from country-wide events like Sziget Festival or Hegyalja Festival, local festivals started to emerge since the first half of the first decade of the new millennium, with the aim to showcase known bands in all regions of Hungary.[41]

Growing out of a low-profile student meeting in 1993, Sziget Festival became one of the largest open-air festival in the world, taking place each summer in the heart of Budapest, the 108 hectare Óbudai island. Visited by hundreds of thousands from all over Europe, it is the largest cultural event in Hungary, inviting world-class performers from all genres.[42]

Also having a history from 1993, VOLT Festival is the second-largest music festival in the country,[43] held each year in Sopron. With a colorful mix of musical styles, and popularity increasing each year, is considered to be the "cheaper version" of Sziget. Also founded by the Sziget management, Balaton Sound is a festival of mainly electronic music, held yearly in Zamárdi, next to Lake Balaton. With prestigious performers and exclusive surroundings, it tries to position itself as a high-standard event.[44]

Hegyalja Festival, held in Tokaj, the historic wine-region of the country, is the largest such event in the Northern part. Visited by 50.000 guests each year, it showcases mainly hard rock and rock formations, but many more genres are present. BalaTone, another major event near lake Balaton is held in Zánka. Magyar Sziget, held in Verőce, has a nationalist theme, with mainly right-wing performers, bands representing the recently emerged nationalistic rock, folk and folk-rock.[45]

As a tradition, each larger University (or more precisely, its students' union) holds a periodical music festival, "University Days", of various size, the largest one is PEN (of the University of Pécs). Examples of smaller, local festivals are SZIN held in Szeged, the free Utcazene Fesztivál held on the streets of Veszprém, Pannónia Fesztivál in Várpalota,[46] or the recently (2008) started Fishing on Orfű, held on the beach of the Orfű lake.

Funding

[edit]The Hungarian Ministry of Culture helps to fund some forms of music, as does the government-run National Cultural Fund. Non-profit organisations in Hungary include the Hungarian Jazz Alliance and the Hungarian Music Council.[47]

References

[edit]- Broughton, Simon (2000). "A Musical Mother Tongue". In Mark Ellingham; James McConnachie; Orla Duane (eds.). Rough Guide to World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London: Rough Guides. pp. 159–167. ISBN 1-85828-636-0.

- Szabolcsi, Bence. "A Concise History of Hungarian music". Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- "From Táncház to concert band". Central Europe Review. Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Beat and Rock Music in Hungary". Central Europe Review. Archived from the original on 2018-09-01. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Cotton, Marian; Adelaide Bradburn (1953). Music Throughout the World. Summy-Birchard Company.

- "Hand Grenade Explodes Outside Home of Ethnic Hungarian Leader in Vojvodina, Serbia". Hungarian Human Right Foundation. Retrieved 2007-08-24.[permanent dead link]

- Kroó, György. "Hungarian Music Since 1945". Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- Szalipszki, Endre (ed.). "Brief History of Music in Hungary (pdf)" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs Budapest. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- Nettl, Bruno (1965). Folk and Traditional Music of the Western Continents. Prentice Hall, Inc.

- Bálint, Sárosi. "Hungarian Gypsy Music: Whose Heritage?". The Hungarian Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2005-10-04. Retrieved 2005-09-24.

- Stephen, Sisa. "Hungarian Music". The Spirit of Hungary. Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- "Improvising in the dark: Hungarian jazz on long road to mass appeal". On the Globe. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- "Hungarian Music". Hungary.hu. Archived from the original on 2004-08-13. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Broughton, pg. 159

Broughton claims that Hungary's "infectious sound has been surprisingly influential on neighbouring countries (thanks perhaps to the common Austro-Hungarian history) and it is not uncommon to hear Hungarian-sounding tunes in Romania, Slovakia and Poland". - ^ Szalipszki, pg.12

Refers to the country as "widely considered" to be a "home of music". - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Broughton, p. 159-167

- ^ Szabolcsi, Bence (1955). "A Concise History of Hungarian Music". Digital Library of Hungarian Studies. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- ^ Ballasa, Iván; Ortutay, Gyula (1979). "Hungarian Folk Music and Folk Instruments". Digital Library of Hungarian Studies. Retrieved 2024-03-22.

- ^ Szabolcsi, The Specific Conditions of Hungarian Musical Development

"Every experiment, made from Hungarian antedecents and on Hungarian soil, to create a conscious musical culture (music written by composers, as different from folk music), had instinctively or consciously striven to develop widely and universally the musical world of the folk song. Folk poetry and folk music were deeply embedded in the collective Hungarian people’s culture, and this unity did not cease to be effective even when it was given from and expression by individual creative artists, performers and poets." - ^ a b c d e f g h i j "BENCE SZABOLCSI: A CONCISE HISTORY OF HUNGARIAN MUSIC". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Introduction to Hungary".

- ^ Broughton, pp. 159 - 167

- ^ a b c d e Nettl

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Brief History of Music in Hungary (pdf)" (PDF). Mfa.gov.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ Zolnay László: A magyar muzsika régi századaiból. Magvető Könyvkiadó, 1977, pp. 304.

- ^ Broughton, pg. 160 Just as bagpipes mean Scotland, so Gypsy bands mean Hungary in the popular imagination. When nationalist composers like Liszt composed... they took as their models the music of the urban Gypsy orchestras.

- ^ a b "Sarosi". 2.4dcomm.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2005. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ a b c d Cotton

- ^ Szabolcsi, The "Verbunkos": The National Musical Style of the Nineteenth Century When around 1800 the leading role of the new dance music was taken over by János Bihari, János Lavotta and Antal Csermák... its melodic and rhythmical enrichment was such that the "verbunkos" immediately became the most important expression of the Hungarian musical Romanticism. It even assumed the role of the representative art of nineteenth-century Hungary, the role of national music.

- ^ a b "Sisa". Hungarian-history.hu. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ a b c "Central Europe Review - Hungarian Music Special: Ghymes Interview". Ce-review.org. Archived from the original on August 19, 2000. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Szabolcsi, The Instrumental Music of the Romantic Period: Liszt and Mosonyi: The Programme of Romanticism They are thus, all three of them, "occidentalists", but the influence of their movement on Hungarian music is unsurpassed even by their successors, because in addition to their individual abilities they bring about an unprecedented artistic intensification of the Romantic musical idiom, which is practically consumed by this extreme passion.

- ^ Sárosi, Bálint. Cigányzene [Gypsy music] (Budapest, 1971; Eng. trans., rev., 1978; Ger. trans., 1977)

- ^ Szabolcsi, New Hungarian Music Their art was not popular art. It was more than that. It was an individual avowal related to the most profound characteristics of their people, an extensive expression of creative forces. These expressions were, as a matter of course, related to every great historical tradition of the Hungarian people.

- ^ Kroó, György The ideal of popular art is from 1949 gradually replaced by state art, the practice of a controlled and administratively directed musical life. Commitment and ideological affiliation are measured by the musical style of a composer; the ignominious adjectives "formalistic" and "cosmopolitan" gain currency. That the progressive musical style is identified with the major mode, the classical aria, rondo or sonata form, the chord sequences distilled from Kodály works and proclamatory composition becomes exalted into an unwritten law.

- ^ Grove Music Online

- ^ "Hungarian Music since 1945by György Kroó". mek.oszk.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Central Cafe set up a Coffee Jazz band". Az Ujság. 25 February 1922.

- ^ a b c d e "Central Europe Review - Beat and Rock Music in Hungary". Ce-review.org. Archived from the original on 1 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Loucile Chaufour (dir.) East Punk Memories. Icarus Films, 2012

- ^ Szemere, Anna. Up from the Underground. The Culture of Rock in Postsocialist Hungary. Penn State Press, 2001.

- ^ "Még mindig "Tilos" - beszélgetés Palotai Zsolttal". palotai.hu (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on 2002-07-20. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ^ "Visszatekintés: Rave Magyarországon". Ravers-unite.blog.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Budapest Parádé: Hírek". Archived from the original on 2007-04-04. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Tilos Rádió 90,3MHz". tilos.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Anima Sound System". Archived from the original on 2007-05-26. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ^ "Belga". Belga.hu. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "hlo - Hungarian Literature Online". Hlo.hu. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "MNO Magyar Nemzet Online". Archived from the original on 2008-11-10. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Official Website of Ektomorf". Archived from the original on 2009-07-25. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-27. Retrieved 2014-01-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "News of the Orchestra". Bfz.hu. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "News". Bfz.hu. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Koncentrálódik a fesztiválpiac". Index.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Index - Kult - Szigettörténelem 1993-1999". index.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "A VOLT Fesztivál története Sopron nyitólapja". Sopron.co.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Holnap kezdődik a Balaton Sound". Index.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "Szigetben őrzött identitás". Archived from the original on 2008-05-26. Retrieved 2009-06-05.

- ^ "A legolcsóbb fesztivál". Index.hu. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- ^ "On the Globe". Ontheglobe.com. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

Further reading

[edit]- Bartók, Béla (1981). Hungarian Folk Music. Ams Pr. ISBN 0-404-16600-8.

- Dobszay, László (1993). A History of Hungarian Music. Corvina. ISBN 963-13-3498-8.

- Káldy, Gyula (1902). History of Hungarian Music. Reprint Services Corp. ISBN 0-7812-0246-9.

- Kodály, Zoltán (1960). Folk Music of Hungary. Barrie and Rockliff.

- Sárosi, Bálint (1986). Folk Music: Hungarian Musical Idiom. Corvina. ISBN 963-13-2220-3.

- Szemere, Anna (2001). Up From the Underground: The Culture of Rock Music in Postsocialist Hungary. Penn State University Press. ISBN 0-271-02133-0.

- Szitha, Tünde (2000). A magyar zene századai (The Centuries of the Hungarian Music). Magus Kiado. ISBN 963-8278-68-4.

Kárpáti, János (ed), Adams, Bernard (trans) (2011). Music in Hungary: an Illustrated History. Rózsavölgyi. ISBN 978-615-5062-01-8.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- (in French) Audio clips: Traditional music of Hungary. Musée d'ethnographie de Genève. Accessed November 25, 2010.

- Hungarian music summarized at the administrative website of Hungary

- Hungarian Folk Music Collection: Népdalok and Magyar Nóta (5000 melodies).

- :Urban Hungarian music or Magyar Nóta: YouTube playlists