Christology

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christology |

|---|

In Christianity, Christology[a] is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Different denominations have different opinions on questions such as whether Jesus was human, divine, or both, and as a messiah what his role would be in the freeing of the Jewish people from foreign rulers or in the prophesied Kingdom of God, and in the salvation from what would otherwise be the consequences of sin.[1][2][3][4][5]

The earliest Christian writings gave several titles to Jesus, such as Son of Man, Son of God, Messiah, and Kyrios, which were all derived from Hebrew scripture. These terms centered around two opposing themes, namely "Jesus as a preexistent figure who becomes human and then returns to God", versus adoptionism – that Jesus was human who was "adopted" by God at his baptism, crucifixion, or resurrection.[web 1]

While there was a consensus as of 2007 that the divinity of Christ was a later development,[6] there are scholars now who argue that the historical Jesus claimed to be God.[7][8] Most scholars now argue that a high Christology existed prior to Paul.[9] Brant Pitre's argument that Jesus claimed to be divine has been particularly well received, obtaining the endorsement of noted scholars Dale C. Allison Jr., Chris Tilling, Tucker Ferda, and Christine Jacobi. [10]

From the second to the fifth centuries, the relation of the human and divine nature of Christ was a major focus of debates in the early church and at the first seven ecumenical councils. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 issued a formulation of the hypostatic union of the two natures of Christ, one human and one divine, "united with neither confusion nor division".[11] Most of the major branches of Western Christianity and Eastern Orthodoxy subscribe to this formulation,[11][12] while many branches of Oriental Orthodox Churches reject it,[13][14][15] subscribing to miaphysitism.

Definition and approaches

[edit]Christology (from the Greek Χριστός, Khristós and -λογία, -logia), literally 'the understanding of Christ',[16] is the study of the nature (person) and work (role in salvation)[note 1] of Jesus Christ.[1][4][3][web 1][web 4][note 2] It studies Jesus Christ's humanity and divinity, and the relation between these two aspects;[5] and the role he plays in salvation.

"Ontological Christology" analyzes the nature or being[web 5] of Jesus Christ. "Functional Christology" analyzes the works of Jesus Christ, while "soteriological Christology" analyzes the "salvific" standpoints of Christology.[19]

Several approaches can be distinguished within Christology.[note 3] The term Christology from above[20] or high Christology[21] refers to approaches that include aspects of divinity, such as Lord and Son of God, and the idea of the pre-existence of Christ as the Logos ('the Word'),[22][21][23] as expressed in the prologue to the Gospel of John.[note 4] These approaches interpret the works of Christ in terms of his divinity. According to Pannenberg, Christology from above "was far more common in the ancient Church, beginning with Ignatius of Antioch and the second century Apologists."[23][24] The term Christology from below[25] or low Christology[21] refers to approaches that begin with the human aspects and the ministry of Jesus (including the miracles, parables, etc.) and move towards his divinity and the mystery of incarnation.[22][21]

Person of Christ

[edit]

A basic Christological teaching is that the person of Jesus Christ is both human and divine. The human and divine natures of Jesus Christ apparently (prosopic) form a duality, as they coexist within one person (hypostasis).[26] There are no direct discussions in the New Testament regarding the dual nature of the Person of Christ as both divine and human,[26] and since the early days of Christianity, theologians have debated various approaches to the understanding of these natures, at times resulting in ecumenical councils, and schisms.[26]

Some historical christological doctrines gained broad support:

- Monophysitism (Monophysite controversy, 3rd–8th centuries): After the union of the divine and the human in the historical incarnation, Jesus Christ had only a single nature. Monophysitism was condemned as heretical by the Council of Chalcedon (451).

- Miaphysitism (Oriental Orthodox churches): In the person of Jesus Christ, divine nature and human nature are united in a compound nature ('physis').

- Dyophysitism (Eastern Orthodox Church, Catholic Church, Church of the East, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and the Reformed Churches): Christ maintained two natures, one divine and one human, after the Incarnation; articulated by the Chalcedonian Definition.

- Monarchianism (including Adoptionism and Modalism): God as one, in contrast to the doctrine of the Trinity. Condemned as heretical in the Patristic era but followed today by certain groups of Nontrinitarians.

Influential Christologies which were broadly condemned as heretical[note 5] are:

- Docetism (3rd–4th centuries) claimed the human form of Jesus was mere semblance without any true reality.

- Arianism (4th century) viewed the divine nature of Jesus, the Son of God, as distinct and inferior to God the Father, e.g., by having a beginning in time.

- Nestorianism (5th century) considered the two natures (human and divine) of Jesus Christ almost entirely distinct.

- Monothelitism (7th century), considered Christ to have only one will.

Various church councils, mainly in the 4th and 5th centuries, resolved most of these controversies, making the doctrine of the Trinity orthodox in nearly all branches of Christianity. Among them, only the Dyophysite doctrine was recognized as true and not heretical, belonging to the Christian orthodoxy and deposit of faith.

Salvation

[edit]In Christian theology, atonement is the method by which human beings can be reconciled to God through Christ's sacrificial suffering and death.[29] Atonement is the forgiving or pardoning of sin in general and original sin in particular through the suffering, death and resurrection of Jesus,[web 6] enabling the reconciliation between God and his creation. Due to the influence of Gustaf Aulèn's (1879–1978) Christus Victor (1931), the various theories or paradigmata of atonement are often grouped as "classical paradigm", "objective paradigm", and the "subjective paradigm":[30][31][32][33]

- Classical paradigm:[note 6]

- Ransom theory of atonement, which teaches that the death of Christ was a ransom sacrifice, usually said to have been paid to Satan or to death itself, in some views paid to God the Father, in satisfaction for the bondage and debt on the souls of humanity as a result of inherited sin. Gustaf Aulén reinterpreted the ransom theory,[34] calling it the Christus Victor doctrine, arguing that Christ's death was not a payment to the Devil, but defeated the powers of evil, which had held humankind in their dominion.;[35][note 7]

- Recapitulation theory,[37] which says that Christ succeeded where Adam failed. Theosis ('divinization') is a "corollary" of the recapitulation.[38]

- Objective paradigm:

- Satisfaction theory of atonement,[note 8] developed by Anselm of Canterbury (1033/4–1109), which teaches that Jesus Christ suffered crucifixion as a substitute for human sin, satisfying God's just wrath against humankind's transgression due to Christ's infinite merit.[39]

- Penal substitution, also called "forensic theory" and "vicarious punishment", which was a development by the Reformers of Anselm's satisfaction theory.[40][41][note 9][note 10] Instead of considering sin as an affront to God's honour, it sees sin as the breaking of God's moral law. Penal substitution sees sinful man as being subject to God's wrath, with the essence of Jesus' saving work being his substitution in the sinner's place, bearing the curse in the place of man.

- Governmental theory of atonement, "which views God as both the loving creator and moral Governor of the universe."[43]

- Subjective paradigm:

- Moral influence theory of atonement,[note 11] developed, or most notably propagated, by Abelard (1079–1142),[44][45] who argued that "Jesus died as the demonstration of God's love", a demonstration which can change the hearts and minds of the sinners, turning back to God.[44][46]

- Moral example theory, developed by Faustus Socinus (1539–1604) in his work De Jesu Christo servatore (1578), who rejected the idea of "vicarious satisfaction".[note 12] According to Socinus, Jesus' death offers humanity a perfect example of self-sacrificial dedication to God.[46]

Other theories are the "embracement theory" and the "shared atonement" theory.[47][48]

Early Christologies (1st century)

[edit]Early notions of Christ

[edit]The earliest christological reflections were shaped by both the Jewish background of the earliest Christians, and by the Greek world of the eastern Mediterranean in which they operated.[49][web 1][note 13] The earliest Christian writings give several titles to Jesus, such as Son of Man, Son of God, Messiah, and Kyrios, which were all derived from Hebrew scripture.[web 1][21] According to Matt Stefon and Hans J. Hillerbrand:

Until the middle of the 2nd century, such terms emphasized two themes: that of Jesus as a preexistent figure who becomes human and then returns to God and that of Jesus as a creature elected and "adopted" by God. The first theme makes use of concepts drawn from Classical antiquity, whereas the second relies on concepts characteristic of ancient Jewish thought. The second theme subsequently became the basis of "adoptionist Christology" (see adoptionism), which viewed Jesus' baptism as a crucial event in his adoption by God.[web 1]

Historically in the Alexandrian school of thought (fashioned on the Gospel of John), Jesus Christ is the eternal Logos who already possesses unity with the Father before the act of Incarnation.[54] In contrast, the Antiochian school viewed Christ as a single, unified human person apart from his relationship to the divine.[54][note 14]

Pre-existence

[edit]The notion of pre-existence is deeply rooted in Jewish thought, and can be found in apocalyptic thought and among the rabbis of Paul's time,[56] but Paul was most influenced by Jewish-Hellenistic wisdom literature, where "'Wisdom' is extolled as something existing before the world and already working in creation.[56] According to Witherington, Paul "subscribed to the christological notion that Christ existed prior to taking on human flesh[,] founding the story of Christ [...] on the story of divine Wisdom".[57][note 15]

Kyrios

[edit]The title Kyrios for Jesus is central to the development of New Testament Christology.[58] In the Septuagint it translates the Tetragrammaton, the holy Name of God. As such, it closely links Jesus with God – in the same way a verse such as Matthew 28:19, "The Name (singular) of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit".[59]

Kyrios is also conjectured to be the Greek translation of Aramaic Mari, which in everyday Aramaic usage was a very respectful form of polite address, which means more than just 'teacher' and was somewhat similar to 'rabbi'. While the term Mari expressed the relationship between Jesus and his disciples during his life, the Greek Kyrios came to represent his lordship over the world.[60]

The early Christians placed Kyrios at the center of their understanding, and from that center attempted to understand the other issues related to the Christian mysteries.[58] The question of the deity of Christ in the New Testament is inherently related to the Kyrios title of Jesus used in the early Christian writings and its implications for the absolute lordship of Jesus. In early Christian belief, the concept of Kyrios included the pre-existence of Christ, for they believed if Christ is one with God, he must have been united with God from the very beginning.[58][61]

Development of "low Christology" and "high Christology"

[edit]Two fundamentally different Christologies developed in the early Church, namely a "low" or adoptionist Christology, and a "high" or "incarnation" Christology.[9] The chronology of the development of these early Christologies is a matter of debate within contemporary scholarship.[62][63][64][web 7]

The "low Christology" or "adoptionist Christology" is the belief "that God exalted Jesus to be his Son by raising him from the dead",[65] thereby raising him to "divine status".[web 8] According to the "evolutionary model"[66] or evolutionary theories,[67] the Christological understanding of Jesus developed over time,[68][69][70] as witnessed in the Gospels,[63] with the earliest Christians believing that Jesus was a human who was exalted, or else adopted as God's Son,[71][72] when he was resurrected.[70][73] Later beliefs shifted the exaltation to his baptism, birth, and subsequently to the idea of his pre-existence, as witnessed in the Gospel of John.[70] This "evolutionary model" was proposed by proponents of the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule, especially Wilhelm Bousset's influential Kyrios Christos (1913).[71] This evolutionary model was very influential, and the "low Christology" has long been regarded as the oldest Christology.[74][75][web 8][note 16]

The other early Christology is "high Christology", which is "the view that Jesus was a pre-existent divine being who became a human, did the Father's will on earth, and then was taken back up into heaven whence he had originally come",[web 8][76] and from where he appeared on earth.[note 17] According to Bousset, this "high Christology" developed at the time of Paul's writing, under the influence of Gentile Christians, who brought their pagan Hellenistic traditions to the early Christian communities, introducing divine honours to Jesus.[77] According to Casey and Dunn, this "high Christology" developed after the time of Paul, at the end of the first century CE when the Gospel of John was written.[78]

Since the 1970s, these late datings for the development of a "high Christology" have been contested,[79] and a majority of scholars argue that this "high Christology" existed already before the writings of Paul.[9][note 18] According to the "New Religionsgeschichtliche Schule",[79][web 10] or the Early High Christology Club,[web 11] which includes Martin Hengel, Larry Hurtado, N. T. Wright, and Richard Bauckham,[79][web 11] this "incarnation Christology" or "high Christology" did not evolve over a longer time, but was a "big bang" of ideas which were already present at the start of Christianity, and took further shape in the first few decades of the church, as witnessed in the writings of Paul.[79][web 11][web 8][note 19] Some 'Early High Christology' proponents scholars argue that this "high Christology" may go back to Jesus himself.[84][web 7]

There is a controversy regarding whether Jesus himself claimed to be divine. In Honest to God, then-Bishop of Woolwich, John A. T. Robinson, questioned the idea.[85] John Hick, writing in 1993, mentioned changes in New Testament studies, citing "broad agreement" that scholars do not today support the view that Jesus claimed to be God, quoting as examples Michael Ramsey (1980), C. F. D. Moule (1977), James Dunn (1980), Brian Hebblethwaite (1985) and David Brown (1985).[86] Larry Hurtado, who argues that the followers of Jesus within a very short period developed an exceedingly high level of devotional reverence to Jesus,[87] at the same time rejects the view that Jesus made a claim to messiahship or divinity to his disciples during his life as "naive and ahistorical".[failed verification] According to Gerd Lüdemann, the broad consensus among modern New Testament scholars is that the proclamation of the divinity of Jesus was a development within the earliest Christian communities.[6] N. T. Wright points out that arguments over the claims of Jesus regarding divinity have been passed over by more recent scholarship, which sees a more complex understanding of the idea of God in first century Judaism.[88] However, Andrew Loke argues that if Jesus did not claim and show himself to be truly divine and rise from the dead, the earliest Christian leaders who were devout ancient monotheistic Jews would have regarded Jesus as merely a teacher or a prophet; they would not have come to the widespread agreement that he was truly divine, which they did.[89][90] Brant Pitre also argues that the Historical Jesus claimed to be divine and was the origin of high Christology. [91]

New Testament writings

[edit]The study of the various Christologies of the Apostolic Age is based on early Christian documents.[2]

Paul

[edit]

The oldest Christian sources are the writings of Paul.[92] The central Christology of Paul conveys the notion of Christ's pre-existence[56][57] and the identification of Christ as Kyrios.[93] Both notions already existed before him in the early Christian communities, and Paul deepened them and used them for preaching in the Hellenistic communities.[56]

What exactly Paul believed about the nature of Jesus cannot be determined decisively. In Philippians 2, Paul states that Jesus was preexistent and came to Earth "by taking the form of a servant, being made in human likeness". This sounds like an incarnation Christology. In Romans 1:4, however, Paul states that Jesus "was declared with power to be the Son of God by his resurrection from the dead", which sounds like an adoptionistic Christology, where Jesus was a human being who was "adopted" after his death. Different views would be debated for centuries by Christians and finally settled on the idea that he was both fully human and fully divine by the middle of the 5th century in the Council of Ephesus. Paul's thoughts on Jesus' teachings, versus his nature and being, are more defined, in that Paul believed Jesus was sent as an atonement for the sins of everyone.[94][95][96]

The Pauline epistles use Kyrios to identify Jesus almost 230 times, and express the theme that the true mark of a Christian is the confession of Jesus as the true Lord.[97] Paul viewed the superiority of the Christian revelation over all other divine manifestations as a consequence of the fact that Christ is the Son of God.[web 4]

The Pauline epistles also advanced the "cosmic Christology"[note 20] later developed in the Gospel of John,[99] elaborating the cosmic implications of Jesus' existence as the Son of God: "Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come."[100] Paul writes that Christ came to draw all back to God: "Through him God was pleased to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven" (Colossians 1:20);[101][102] in the same epistle, he writes that "He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation" (Colossians 1:15).[103][93][98]

The Gospels

[edit]

The synoptic Gospels date from after the writings of Paul. They provide episodes from the life of Jesus and some of his works, but the authors of the New Testament show little interest in an absolute chronology of Jesus or in synchronizing the episodes of his life,[104] and as in John 21:25, the Gospels do not claim to be an exhaustive list of his works.[2]

Christologies that can be gleaned from the three synoptic Gospels generally emphasize the humanity of Jesus, his sayings, his parables, and his miracles. The Gospel of John provides a different perspective that focuses on his divinity.[web 4] The first 14 verses of the Gospel of John are devoted to the divinity of Jesus as the Logos, usually translated as "Word", along with his pre-existence, and they emphasize the cosmic significance of Christ, e.g.: "All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made."[105] In the context of these verses, the Word made flesh is identical with the Word who was in the beginning with God, being exegetically equated with Jesus.[web 4]

Controversies and ecumenical councils (2nd–8th century)

[edit]Post-Apostolic controversies

[edit]Following the Apostolic Age, from the second century onwards, a number of controversies developed about how the human and divine are related within the person of Jesus.[106][107] As of the second century, a number of different and opposing approaches developed among various groups. In contrast to prevailing monoprosopic views on the Person of Christ, alternative dyoprosopic notions were also promoted by some theologians, but such views were rejected by the ecumenical councils. For example, Arianism did not endorse divinity, Ebionism argued Jesus was an ordinary mortal, while Gnosticism held docetic views which argued Christ was a spiritual being who only appeared to have a physical body.[27][28] The resulting tensions led to schisms within the church in the second and third centuries, and ecumenical councils were convened in the fourth and fifth centuries to deal with the issues.[citation needed]

Although some of the debates may seem to various modern students to be over a theological iota, they took place in controversial political circumstances, reflecting the relations of temporal powers and divine authority, and certainly resulted in schisms, among others that separated the Church of the East from the Church of the Roman Empire.[108][109]

First Council of Nicaea (325) and First Council of Constantinople (381)

[edit]In 325, the First Council of Nicaea defined the persons of the Godhead and their relationship with one another, decisions which were ratified at the First Council of Constantinople in 381. The language used was that the one God exists in three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit); in particular, it was affirmed that the Son was homoousios (of the same being) as the Father. The Nicene Creed declared the full divinity and full humanity of Jesus.[110][111][112] After the First Council of Nicaea in 325 the Logos and the second Person of the Trinity were being used interchangeably.[113]

First Council of Ephesus (431)

[edit]In 431, the First Council of Ephesus was initially called to address the views of Nestorius on Mariology, but the problems soon extended to Christology, and schisms followed. The 431 council was called because in defense of his loyal priest Anastasius, Nestorius had denied the Theotokos title for Mary and later contradicted Proclus during a sermon in Constantinople. Pope Celestine I (who was already upset with Nestorius due to other matters) wrote about this to Cyril of Alexandria, who orchestrated the council. During the council, Nestorius defended his position by arguing there must be two persons of Christ, one human, the other divine, and Mary had given birth only to a human, hence could not be called the Theotokos, i.e. "the one who gives birth to God". The debate about the single or dual nature of Christ ensued in Ephesus.[114][115][116][117]

The First Council of Ephesus debated miaphysitism (two natures united as one after the hypostatic union) versus dyophysitism (coexisting natures after the hypostatic union) versus monophysitism (only one nature) versus Nestorianism (two hypostases). From the Christological viewpoint, the council adopted Mia Physis ('but being made one', κατὰ φύσιν) – Council of Ephesus, Epistle of Cyril to Nestorius, i.e. 'one nature of the Word of God incarnate' (μία φύσις τοῦ θεοῦ λόγου σεσαρκωμένη, mía phýsis toû theoû lógou sesarkōménē). In 451, the Council of Chalcedon affirmed dyophysitism. The Oriental Orthodox rejected this and subsequent councils and continued to consider themselves as miaphysite according to the faith put forth at the Councils of Nicaea and Ephesus.[118][119] The council also confirmed the Theotokos title and excommunicated Nestorius.[120][121]

Council of Chalcedon (451)

[edit]

The 451 Council of Chalcedon was highly influential, and marked a key turning point in the christological debates.[122] It is the last council which many Lutherans, Anglicans and other Protestants consider ecumenical.[12][13]

The Council of Chalcedon fully promulgated the Western dyophysite understanding put forth by Pope Leo I of Rome of the hypostatic union, the proposition that Christ has one human nature (physis) and one divine nature (physis), each distinct and complete, and united with neither confusion nor division.[106][107] Most of the major branches of Western Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and Reformed), Church of the East,[123] Eastern Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy subscribe to the Chalcedonian Christological formulation, while many branches of Oriental Orthodox Churches (Syrian Orthodoxy, Coptic Orthodoxy, Ethiopian Orthodoxy, and Armenian Apostolicism) reject it.[13][14][15]

Although the Chalcedonian Creed did not put an end to all christological debate, it did clarify the terms used and became a point of reference for many future Christologies.[13][14][15] But it also broke apart the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the fifth century,[122] and unquestionably established the primacy of Rome in the East over those who accepted the Council of Chalcedon. This was reaffirmed in 519, when the Eastern Chalcedonians accepted the Formula of Hormisdas, anathematizing all of their own Eastern Chalcedonian hierarchy, who died out of communion with Rome from 482 to 519.

Fifth–Seventh Ecumenical Council (553, 681, 787)

[edit]The Second Council of Constantinople in 553 interpreted the decrees of Chalcedon, and further explained the relationship of the two natures of Jesus. It also condemned the alleged teachings of Origen on the pre-existence of the soul, and other topics.[web 12]

The Third Council of Constantinople in 681 declared that Christ has two wills of his two natures, human and divine, contrary to the teachings of the Monothelites,[web 13] with the divine will having precedence, leading and guiding the human will.[124]

The Second Council of Nicaea was called under the Empress Regent Irene of Athens in 787, known as the second of Nicaea. It supports the veneration of icons while forbidding their worship. It is often referred to as "The Triumph of Orthodoxy".[web 14]

9th–11th century

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (February 2019) |

Eastern Christianity

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (March 2019) |

Western medieval Christology

[edit]The Franciscan piety of the 12th and 13th centuries led to "popular Christology". Systematic approaches by theologians, such as Thomas Aquinas, are called "scholastic Christology".[125]

In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas provided the first systematic Christology that consistently resolved a number of the existing issues.[126] In his Christology from above, Aquinas also championed the principle of perfection of Christ's human attributes.[127][128][129]

The Middle Ages also witnessed the emergence of the "tender image of Jesus" as a friend and a living source of love and comfort, rather than just the Kyrios image.[130]

Reformation

[edit]Article 10 of the Belgic Confession, a confessional standard of the Reformed faith, subscribes to Nicene orthodoxy regarding the deity of Christ. The article places emphasis on the eternal generation of the Son and the eternal divine nature of Christ as Creator.

We believe that Jesus Christ, according to his divine nature, is the only begotten Son of God, begotten from eternity, not made nor created (for then He should be a creature), but co-essential and co-eternal with the Father, "the express image of His person, and the brightness of His glory" (Hebrews 1:3), equal unto him in all things. He is the Son of God, not only from the time that He assumed our nature, but from all eternity, as these testimonies, when compared together, teach us. Moses says that God created the world; and John saith that "all things were made by that Word" (John 1:3), which he calls God. And the apostle says that God made the worlds by His Son (Hebrews 1:2); likewise, that "God created all things by Jesus Christ" (Ephesians 3:9). Therefore, it must needs follow, that he who is called God, the Word, the Son, and Jesus Christ did exist at that time, when all things were created by him. Therefore, the prophet Micah says, "His goings forth have been from of old, from everlasting" (Micah 5:2). And the apostle: "He has neither beginning of days, nor end of life" (Hebrews 7:3). He therefore is that true, eternal, and almighty God, whom we invoke, worship and serve.[131]

John Calvin maintained there was no human element in the Person of Christ which could be separated from the Person of the Word.[132] Calvin also emphasized the importance of the "Work of Christ" in any attempt at understanding the Person of Christ and cautioned against ignoring the works of Jesus during his ministry.[133]

Modern developments

[edit]Liberal Protestant theology

[edit]The 19th century saw the rise of Liberal Protestant theology, which questioned the dogmatic foundations of Christianity, and approached the Bible with critical-historical tools.[web 15] The divinity of Jesus became of less emphasis or importance, and was replaced with an focus on the ethical aspects of his teachings.[134][note 21]

Roman Catholicism

[edit]Catholic theologian Karl Rahner sees the purpose of modern Christology as to formulate the Christian belief that "God became man and that God-made-man is the individual Jesus Christ" in a manner that this statement can be understood consistently, without the confusions of past debates and mythologies.[136][note 22] Rahner pointed out the coincidence between the Person of Christ and the Word of God, referring to Mark 8:38 and Luke 9:26 which state whoever is ashamed of the words of Jesus is ashamed of the Lord himself.[138]

Hans von Balthasar argued the union of the human and divine natures of Christ was achieved not by the "absorption" of human attributes, but by their "assumption". Thus, in his view, the divine nature of Christ was not affected by the human attributes and remained forever divine.[139]

Topics

[edit]Nativity and the Holy Name

[edit]The Nativity of Jesus impacted the Christological issues about his person from the earliest days of Christianity. Luke's Christology centers on the dialectics of the dual natures of the earthly and heavenly manifestations of existence of the Christ, while Matthew's Christology focuses on the mission of Jesus and his role as the savior.[140][141] The salvific emphasis of Matthew 1:21 later impacted the theological issues and the devotions to Holy Name of Jesus.[142][143][144]

Matthew 1:23 provides a key to the "Emmanuel Christology" of Matthew. Beginning with 1:23, the Gospel of Matthew shows a clear interest in identifying Jesus as "God with us" and in later developing the Emmanuel characterization of Jesus at key points throughout the rest of the Gospel.[145] The name 'Emmanuel' does not appear elsewhere in the New Testament, but Matthew builds on it in Matthew 28:20 ("I am with you always, even unto the end of the world") to indicate Jesus will be with the faithful to the end of the age.[145][146] According to Ulrich Luz, the Emmanuel motif brackets the entire Gospel of Matthew between 1:23 and 28:20, appearing explicitly and implicitly in several other passages.[147]

Crucifixion and resurrection

[edit]The accounts of the crucifixion and subsequent resurrection of Jesus provides a rich background for christological analysis, from the canonical Gospels to the Pauline Epistles.[148]

A central element in the christology presented in the Acts of the Apostles is the affirmation of the belief that the death of Jesus by crucifixion happened "with the foreknowledge of God, according to a definite plan".[149] In this view, as in Acts 2:23, the cross is not viewed as a scandal, for the crucifixion of Jesus "at the hands of the lawless" is viewed as the fulfilment of the plan of God.[149][150]

Paul's Christology has a specific focus on the death and resurrection of Jesus. For Paul, the crucifixion of Jesus is directly related to his resurrection and the term "the cross of Christ" used in Galatians 6:12 may be viewed as his abbreviation of the message of the Gospels.[151] For Paul, the crucifixion of Jesus was not an isolated event in history, but a cosmic event with significant eschatological consequences, as in 1 Corinthians 2:8.[151] In the Pauline view, Jesus, obedient to the point of death (Philippians 2:8), died "at the right time" (Romans 5:6) based on the plan of God.[151] For Paul, the "power of the cross" is not separable from the resurrection of Jesus.[151]

Threefold office

[edit]The threefold office (Latin munus triplex) of Jesus Christ is a Christian doctrine based upon the teachings of the Old Testament. It was described by Eusebius and more fully developed by John Calvin. It states that Jesus Christ performed three functions (or "offices") in his earthly ministry – those of prophet, priest, and king. In the Old Testament, the appointment of someone to any of these three positions could be indicated by anointing him or her by pouring oil over the head. Thus, the term messiah, meaning "anointed one", is associated with the concept of the threefold office. While the office of king is that most frequently associated with the Messiah, the role of Jesus as priest is also prominent in the New Testament, being most fully explained in chapters 7 to 10 of the Book of Hebrews.

Mariology

[edit]Some Christians, notably Roman Catholics, view Mariology as a key component of Christology.[web 16] In this view, not only is Mariology a logical and necessary consequence of Christology, but without it, Christology is incomplete, since the figure of Mary contributes to a fuller understanding of who Christ is and what he did.[152]

Protestants have criticized Mariology because many of its assertions lack any Biblical foundation.[153] Strong Protestant reaction against Roman Catholic Marian devotion and teaching has been a significant issue for ecumenical dialogue.[154]

Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI) expressed this sentiment about Roman Catholic Mariology when in two separate occasions he stated, "The appearance of a truly Marian awareness serves as the touchstone indicating whether or not the christological substance is fully present"[155] and "It is necessary to go back to Mary, if we want to return to the truth about Jesus Christ."[156]

See also

[edit]- Catholic spirituality

- Christian messianic prophecies

- Christian views of Jesus

- Christological argument

- Crucifixion of Jesus

- Doubting Thomas

- Eucharist

- Eutychianism

- Five Holy Wounds

- Genealogy of Jesus

- Great Church

- Great Tribulation

- Harrowing of Hell

- Kingship and Kingdom of God

- Last Judgement

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- Miracles of Jesus

- Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament

- Religious perspectives on Jesus

- Paterology

- Pneumatology

- Rapture

- Scholastic Lutheran Christology

- Second Coming of Christ

- Transfiguration of Jesus

- Universal resurrection

Notes

[edit]- ^ The work of Jesus Christ:

- ^ Definitions:

- Bart Ehrman: "the understanding of Christ";[16] "the nature of Christ – the question of Christology"[1]

- Bird, Evans & Gathercole (2014): "New Testament scholars often speak about "Christology", which is the study of the career, person, nature, and identity of Jesus Christ."[4]

- Raymond Brown (1994): "[C]hristology discusses any evaluation of Jesus in respect to who he was and the role he played in the divine plan."[18]

- Bernard L. Ramm (1993): "Christology is the reflective and systematic study of the person and work of Jesus Christ."[3]

- Matt Stefon, Hans J. Hillerbrand (Encyclopedia Britannica): "Christology, Christian reflection, teaching, and doctrine concerning Jesus of Nazareth. Christology is the part of theology that is concerned with the nature and work of Jesus, including such matters as the Incarnation, the Resurrection, and his human and divine natures and their relationship."[web 1]

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Christology is that part of theology which deals with Our Lord Jesus Christ. In its full extent it comprises the doctrines concerning both the person of Christ and His works."[web 4]

- ^ Bird, Evans & Gathercole (2014): "There are, of course, many different ways of doing Christology. Some scholars study Christology by focusing on the major titles applied to Jesus in the New Testament, such as "Son of Man", "Son of God", "Messiah", "Lord", "Prince", "Word", and the like. Others take a more functional approach and look at how Jesus acts or is said to act in the New Testament as the basis for configuring beliefs about him. It is possible to explore Jesus as a historical figure (i.e., Christology from below), or to examine theological claims made about Jesus (i.e., Christology from above). Many scholars prefer a socio-religious method by comparing beliefs about Jesus with beliefs in other religions to identify shared sources and similar ideas. Theologians often take a more philosophical approach and look at Jesus' "ontology" or "being" and debate how best to describe his divine and human natures."[4]

- ^ John 1:1–14

- ^ Heretical Christologies:

- Docetism is the doctrine that the phenomenon of Jesus, his historical and bodily existence, and above all the human form of Jesus, was mere semblance without any true reality. Broadly it is taken as the belief that Jesus only seemed to be human, and that his human form was an illusion. Docetic teachings were attacked by Ignatius of Antioch and were eventually abandoned by proto-orthodox Christians.[27][28]

- Arianism, which viewed Jesus as primarily an ordinary mortal, was condemned as heretical in 325, exonerated in 335, and eventually re-condemned as heretical at the First Council of Constantinople (381).[27][28]

- Nestorianism opposed the concept of hypostatic union, and emphasized a radical distinction between the two natures (human and divine) of Jesus Christ. It was condemned by the Council of Ephesus (431).

- Monothelitism held that although Christ has two natures (Dyophysitism), his will is united. The doctrine was promoted by Emperor Heraclius and Ecumenical Patriarch Sergius I as a compromise position between Chalcedonianism and various minority christologies. It was condemned as heretical by the Third Council of Constantinople (681).

- ^ The "ransom theory" and the "Christ Victor" theory are different, but are generally considered together as Patristic or "classical" theories, to use Gustaf Aulén's nomenclature. These were the traditional understandings of the early Church Fathers.

- ^ According to Pugh, "Ever since [Aulén's] time, we call these patristic ideas the Christus Victor way of seeing the cross."[36]

- ^ Called by Aulén the "scholastic" view

- ^ Penal substitution:

- Vincent Taylor (1956): "the four main types, which have persisted throughout the centuries. The oldest theory is the Ransom Theory [...] It held sway for a thousand years [...] The Forensic Theory is that of the Reformers and their successors."[40]

- Packer (1973): "Luther, Calvin, Zwingli, Melanchthon and their reforming contemporaries were the pioneers in stating it [i.e. the penal substitutionary theory] [...] What the Reformers did was to redefine satisfactio (satisfaction), the main mediaeval category for thought about the cross. Anselm's Cur Deus Homo?, which largely determined the mediaeval development, saw Christ's satisfactio for our sins as the offering of compensation or damages for dishonour done, but the Reformers saw it as the undergoing of vicarious punishment (poena) to meet the claims on us of God's holy law and wrath (i.e. his punitive justice)."[41]

- ^ Mark D. Baker, objecting against the pebal substitution theory, states that "substitution is a broad term that one can use with reference to a variety of metaphors."[42]

- ^ Which Aulén called the "subjective" or "humanistic" view. Propagated, as a critique of the satisfaction view, by Peter Abelard

- ^ Christ suffering for, or punished for, the sinners.

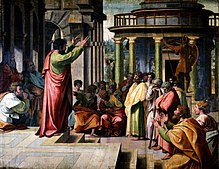

- ^ Early Christians found themselves confronted with a set of new concepts and ideas relating to the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, as well the notions of salvation and redemption, and had to use a new set of terms, images, and ideas in order to deal with them.[49] The existing terms and structures which were available to them were often insufficient to express these religious concepts, and taken together, these new forms of discourse led to the beginnings of Christology as an attempt to understand, explain, and discuss their understanding of the nature of Christ.[49] Early Jewish Christians had to explain their concepts to a Hellenistic audience which had been influenced by Greek philosophy, presenting arguments that at times resonated with, and at times confronted, the beliefs of that audience. This is exemplified by the Apostle Paul's Areopagus sermon that appears in Acts 17:16–34,[50] where Paul is portrayed as attempting to convey the underlying concepts about Christ to a Greek audience. The sermon illustrates some key elements of future christological discourses that were first brought forward by Paul.[51][52][53]

- ^ The views of these schools can be summarized as follows:[55]

- Alexandria: Logos assumes a general human nature;

- Antioch: Logos assumes a specific human being.

- ^ Witherington: "[Christ's Divinity] We have already seen that Paul, in appropriating the language of the christological hymns, subscribed to the christological notion that Christ existed prior to taking on human flesh. Paul spoke of Jesus both as the wisdom of God, his agent in creation (1 Cor 1:24, 30; 8:6; Col 1:15–17; see Bruce, 195), and as the one who accompanied Israel as the 'rock' in the wilderness (1 Cor 10:4). In view of the role Christ plays in 1 Corinthians 10:4, Paul is not founding the story of Christ on the archetypal story of Israel, but rather on the story of divine Wisdom, which helped Israel in the wilderness."[57]

- ^ Ehrman:

- "The earliest Christians held exaltation Christologies in which the human being Jesus was made the Son of God – for example, at his resurrection or at his baptism – as we examined in the previous chapter."[75]

- "Here I'll say something about the oldest Christology, as I understand it. This was what I earlier called a 'low' Christology. I may end up in the book describing it as a 'Christology from below' or possibly an 'exaltation' Christology. Or maybe I'll call it all three things [...] Along with lots of other scholars, I think this was indeed the earliest Christology."[web 9]

- ^ Proponents of Christ's deity argue the Old Testament has many cases of Christophany: "The pre-existence of Christ is further substantiated by the many recorded Christophanies in the Bible."[157] "Christophany" is often[quantify] considered a more accurate term than the term "theophany" due to the belief that all the visible manifestations of God are in fact the preincarnate Christ. Many argue that the appearances of "the Angel of the Lord" in the Old Testament were the preincarnate Christ. "Many understand the angel of the Lord as a true theophany. From the time of Justin on, the figure has been regarded as the preincarnate Logos."[158]

- ^ Richard Bauckham argues that Paul was not so influential that he could have invented the central doctrine of Christianity. Before his active missionary work, there were already groups of Christians across the region. For example, a large group already existed in Rome even before Paul visited the place. The earliest centre of Christianity was the twelve apostles in Jerusalem. Paul himself consulted and sought guidance from the Christian leaders in Jerusalem (Galatians 2:1–2;[80] Acts 9:26–28,[81] 15:2).[82] "What was common to the whole Christian movement derived from Jerusalem, not from Paul, and Paul himself derived the central message he preached from the Jerusalem apostles."[83]

- ^ Loke (2017): "The last group of theories can be called 'Explosion Theories' (one might also call this 'the Big-Bang theory of Christology'!). This proposes that highest Christology was the view of the primitive Palestinian Christian community. The recognition of Jesus as truly divine was not a significant development from the views of the primitive Palestine community; rather, it 'exploded' right at the beginning of Christianity. The proponents of the Explosion view would say that the highest Christology of the later New Testament writings (e.g. Gospel of John) and the creedal formulations of the early church fathers, with their explicit affirmations of the pre-existence and ontological divinity of Christ, are not so much a development in essence but a development in understanding and explication of what was already there at the beginning of the Christian movement. As Bauckham (2008a, x) memorably puts it, 'The earliest Christology was already the highest Christology.' Many proponents of this group of theories have been labelled together as 'the New Religionsgeschichtliche Schule' (Hurtado 2003, 11), and they include such eminent scholars as Richard Bauckham, Larry Hurtado, N. T. Wright and the late Martin Hengel."[79]

- ^ The concept of "cosmic Christology", first elaborated by Saint Paul, focuses on how the arrival of Jesus as the Son of God forever changed the nature of the cosmos.[93][98]

- ^ Gerald O'Collins and Daniel Kendall have called this Liberal Protestant theology "neo-Arianism."[135]

- ^ Grillmeier: "The most urgent task of a contemporary Christology is to formulate the Church's dogma – 'God became man and that God-made-man is the individual Jesus Christ' – in such a way that the true meaning of these statements can be understood, and all trace of a mythology impossible to accept nowadays is excluded."[137]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ehrman 2014, p. 171.

- ^ a b c O'Collins 2009, pp. 1–3.

- ^ a b c Ramm 1993, p. 15.

- ^ a b c d Bird, Evans & Gathercole 2014, p. 134, n. 5.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2014, p. ch. 6–9.

- ^ a b Gerd Lüdemann, "An Embarrassing Misrepresentation" Archived 24 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Free Inquiry, October / November 2007: "the broad consensus of modern New Testament scholars that the proclamation of Jesus's exalted nature was in large measure the creation of the earliest Christian communities."

- ^ Andrew Ter Ern Loke, The Origin of Divine Christology (Cambridge University Press, 2017), pp. 100–135

- ^ Loke, Andrew (18 February 2019). "Is Jesus God? A Historical Evaluation Concerning the Deity of Christ". Ethos Institute. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Ehrman 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Pitre, Brant (2024). Jesus and Divine Christology. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802875129.

- ^ a b Davis 1990, p. 342.

- ^ a b Olson, Roger E. (1999). The Story of Christian Theology: Twenty Centuries of Tradition Reform. InterVarsity Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-8308-1505-0.

- ^ a b c d Armentrout & Boak Slocum 2005, p. 81.

- ^ a b c Espín & Nickoloff 2007, p. 217.

- ^ a b c Beversluis 2000, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2014, p. 108.

- ^ Kärkkäinen 2016.

- ^ Brown 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Chan, Mark L. Y. (2001). Christology from Within and Ahead: Hermeneutics, Contingency, and the Quest for Transcontextual Criteria in Christology. BRILL. pp. 59–62. ISBN 978-90-04-11844-7. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ O'Collins 2009, p. 16-17.

- ^ a b c d e Brown 2004, p. 4.

- ^ a b O'Collins 2009, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Pannenberg 1968, p. 33.

- ^ Bobichon, Philippe (1 January 2011). "Filiation divine du Christ et filiation divine des chrétiens dans les écrits de Justin Martyr". In: Patricio de Navascués Benlloch – Manuel Crespo Losada – Andrés Sáez Gutiérrez (dir.), Filiación. Cultura pagana, religión de Israel, orígenes del cristianismo, vol. III, Madrid, pp. 337-378. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ O'Collins 2009, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Introducing Christian Doctrine by Millard J. Erickson, L. Arnold Hustad 2001, p. 234

- ^ a b c Ehrman 1993.

- ^ a b c McGrath 2007, p. 282.

- ^ "Atonement." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- ^ Weaver 2001, p. 2.

- ^ Beilby & Eddy 2009, pp. 11–20.

- ^ Gustaf Aulen, Christus Victor: An Historical Study of the Three Main Types of the Idea of Atonement, E.T. London: SPCK; New York: Macmillan, 1931

- ^ Vincent Taylor, The Cross of Christ (London: Macmillan & Co, 1956), pp. 71–77 2

- ^ Pugh 2015, p. 8.

- ^ Leon Morris, 'Theories of the Atonement' in Elwell Evangelical Dictionary.

- ^ Pugh 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Pugh 2015, pp. 1, 26.

- ^ Pugh 2015, p. 31.

- ^ Tuomala, Jeffrey (1993), "Christ's Atonement as the Model for Civil Justice", American Journal of Jurisprudence, 38: 221–255, doi:10.1093/ajj/38.1.221, archived from the original on 17 June 2020, retrieved 11 December 2019

- ^ a b Taylor 1956, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Packer 1973.

- ^ Baker 2006, p. 25.

- ^ Beilby & Eddy 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b Weaver 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Beilby & Eddy 2009, p. 18.

- ^ a b Beilby & Eddy 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Jeremiah, David. 2009. Living With Confidence in a Chaotic World, pp. 96 & 124. Nashville, Tennessee: Thomas Nelson, Inc.

- ^ Massengale, Jamey. 2013.Renegade Gospel, The Jesus Manifold

- ^ a b c McGrath 2006, pp. 137–141.

- ^ Acts 17:16–34

- ^ McGrath 2006, pp. 137–41.

- ^ Creation and redemption: a study in Pauline theology by John G. Gibbs 1971 Brill Publishers pp. 151–153

- ^ Mercer Commentary on the New Testament by Watson E. Mills 2003 ISBN 0-86554-864-1 pp. 1109–1110

- ^ a b Charles T. Waldrop (1985). Karl Barth's christology ISBN 90-279-3109-7 pp. 19–23

- ^ Historical Theology: An Introduction by Geoffrey W. Bromiley 2000 ISBN 0567223574 pp. 50–51

- ^ a b c d Grillmeier & Bowden 1975, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Witherington 2009, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Mini S. (1 January 2005). Christology: Biblical And Historical. Mittal Publications. pp. 229–235. ISBN 978-81-8324-007-9. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Matthew 28:19

- ^ The Christology of the New Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. 1 January 1959. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-664-24351-7. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ The Christology of the New Testament. Westminster John Knox Press. 1 January 1959. pp. 234–237. ISBN 978-0-664-24351-7. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Loke 2017.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2014.

- ^ Talbert 2011, p. 3-6.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, pp. 120, 122.

- ^ Netland 2001, p. 175.

- ^ Loke 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Mack 1995.

- ^ Ehrman 2003.

- ^ a b c Bart Ehrman, How Jesus became God, Course Guide

- ^ a b Loke 2017, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Talbert 2011, p. 3.

- ^ Geza Vermez (2008), The Resurrection, pp. 138–139

- ^ Bird 2017, pp. ix, xi.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2014, p. 132.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 122.

- ^ Loke 2017, p. 4.

- ^ Loke 2017, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e Loke 2017, p. 5.

- ^ Galatians 2:1–2

- ^ Acts 9:26–28

- ^ Acts 15:2

- ^ Bauckham 2011, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Loke 2017, p. 6.

- ^ Robinson, John A. T. (1963), Honest to God, p. 72.

- ^ Hick, John, The Metaphor of God Incarnate, page 27 Archived 14 December 2023 at the Wayback Machine. "A further point of broad agreement among New Testament scholars [...] is that the historical Jesus did not make the claim to deity that later Christian thought was to make for him: he did not understand himself to be God, or God the Son, incarnate. [...] such evidence as there is has led the historians of the period to conclude, with an impressive degree of unanimity, that Jesus did not claim to be God incarnate."

- ^ Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). How on earth did Jesus become a god?: historical questions about earliest devotion to Jesus. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. pp. 4–6. ISBN 0-8028-2861-2. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Wright, N. T. (1999). The challenge of Jesus : rediscovering who Jesus was and is. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-8308-2200-3. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ Andrew Ter Ern Loke, The Origin of Divine Christology (Cambridge University Press, 2017), pp. 100–135

- ^ Loke, Andrew (18 February 2019). "Is Jesus God? A Historical Evaluation Concerning the Deity of Christ". Ethos Institute. Archived from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Pitre, Brant (2024). Jesus and Divine Christology. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802875129.

- ^ Ehrman 2014, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Grillmeier & Bowden 1975, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (1977). Paul and Palestinian Judaism. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-1899-5.

- ^ Dunn, James D. G. (1990). Jesus, Paul, and the Law: Studies in Mark and Galatians. Louisville, Kentucky: Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 0-664-25095-5. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. "St. Paul the Apostle – Theological views". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 October 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ O'Collins 2009, p. 142.

- ^ a b Larry R. Helyer (2008). The Witness of Jesus, Paul and John: An Exploration in Biblical Theology. ISBN 0-8308-2888-5 p. 282

- ^ Enslin, Morton S. (1975). "John and Jesus". ZNW. 66 (1–2): 1–18. doi:10.1515/zntw.1975.66.1-2.1. ISSN 1613-009X. S2CID 162364599.

[Per the Gospel of John] No longer is John [the Baptizer] an independent preacher. He is but a voice, or, to change the figure, a finger pointing to Jesus. The baptism story is not told, although it is referred to (John 1:32f). But the baptism of Jesus is deprived of any significance for Jesus – not surprising since the latter has just been introduced as the preexistent Christ, who had been the effective agent responsible for the world's creation. (Enslin, p. 4)

- ^ 2 Corinthians 5:17

- ^ Colossians 1:20

- ^ Zupez, John (2014). "Celebrating God's Plan of Creation/Salvation". Emmanuel. 120: 356–359.

- ^ Colossians 1:15

- ^ Karl Rahner (2004). Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi ISBN 0-86012-006-6 p. 731

- ^ John 1:3

- ^ a b Fahlbusch 1999, p. 463.

- ^ a b Rausch 2003, p. 149.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks: Medieval Sourcebook". sourcebooks.fordham.edu. Vol. XIV, p. 207. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ The Seven Ecumenical Councils of the Undivided Church, trans H. R. Percival, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 2nd Series, ed. P. Schaff and H. Wace, (repr. Grand Rapids MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1955), XIV, pp. 192–142

- ^ Jonathan Kirsch, God Against the Gods: The History of the War Between Monotheism and Polytheism (2004)

- ^ Charles Freeman, The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith and the Fall of Reason (2002)

- ^ Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776–1788), p. 21

- ^ A concise dictionary of theology by Gerald O'Collins 2004 ISBN 0-567-08354-3 pp. 144–145

- ^ Marthaler, Berard L. (1993). The Creed: The Apostolic Faith in Contemporary Theology. Twenty-Third Publications. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-89622-537-4. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Campbell, James P. (June 2010). Mary and the Saints by James P. Campbell, 2005, pp. 17–20. Loyola Press. ISBN 978-0829430301.

- ^ González, Justo L. (1 January 2005). Essential Theological Terms. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-664-22810-1.

- ^ Hall, Stuart George (1992). Doctrine and Practice in the Early Church. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 211–218. ISBN 978-0-8028-0629-1.

- ^ Chafer, Lewis Sperry (1 January 1993). Systematic Theology. Kregel Academic. pp. 382–384. ISBN 978-0-8254-2340-6. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Parry, Ken (10 May 2010). The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. John Wiley & Sons. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4443-3361-9. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Baker, Kenneth (1982). Fundamentals of Catholicism: God, Trinity, Creation, Christ, Mary. Ignatius Press. pp. 228–231. ISBN 978-0-89870-019-0. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Mary, Mother of God by Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson 2004 ISBN 0802822665 p. 84

- ^ a b Price & Gaddis 2006, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, pp. 287–289.

- ^ The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology by Alan Richardson and John Bowden (1983) ISBN 0664227481 p. 169

- ^ Johnson, Mini S. (1 January 2005). Christology: Biblical And Historical. Mittal Publications. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-81-8324-007-9. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Gilson, Etienne (1994), The Christian Philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, p. 502, ISBN 978-0-268-00801-7

- ^ Johnson, Mini S. (1 January 2005). Christology: Biblical And Historical. Mittal Publications. pp. 76–79. ISBN 978-81-8324-007-9. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ O'Collins 2009, p. 208–12.

- ^ Goris, Harm J. M. J. (2002). Aquinas as Authority: A Collection of Studies Presented at the Second Conference of the Thomas Insituut Te Utrecht, December 14-16, 2000. Peeters Publishers. pp. 25–35. ISBN 978-90-429-1074-4. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^ Christology: Key Readings in Christian Thought by Jeff Astley, David Brown, Ann Loades 2009 ISBN 0-664-23269-8 p. 106

- ^ Needham, Nick, ed. (2021). The Three Forms of Unity. Moscow, Idaho: Canon Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9781954887176.

- ^ Calvin's Christology by Stephen Edmondson 2004 ISBN 0-521-54154-9 p. 217

- ^ Calvin's First Catechism by I. John Hesselink 1997 ISBN 0-664-22725-2 p. 217

- ^ Dunn 2003, p. ch. 4.

- ^ O'Collins & Kendall 1996, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Rahner 2004, pp. 755–767.

- ^ Grillmeier 1975, p. 755.

- ^ Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0-86012-006-6 p. 1822

- ^ The eschatology of Hans Urs von Balthasar by Nicholas J. Healy 2005 ISBN 0-19-927836-9 pp. 22–23

- ^ Theology of the New Testament by Georg Strecker 2000 ISBN 0-664-22336-2 pp. 401–403

- ^ Matthew by Grant R. Osborne 2010 ISBN 0-310-32370-3 p. lxxix

- ^ Matthew 1–13 by Manlio Simonetti 2001 ISBN 0-8308-1486-8 p. 17

- ^ Matthew 1-2/ Luke 1–2 by Louise Perrotta 2004 ISBN 0-8294-1541-6 p. 19

- ^ All the Doctrines of the Bible by Herbert Lockyer 1988 ISBN 0-310-28051-6 p. 159

- ^ a b Matthew's Emmanuel by David D. Kupp 1997 ISBN 0-521-57007-7 pp. 220–224

- ^ Who do you say that I am?: essays on Christology by Jack Dean Kingsbury, Mark Allan Powell, David R. Bauer 1999 ISBN 0-664-25752-6 p. 17

- ^ The theology of the Gospel of Matthew by Ulrich Luz 1995 ISBN 0-521-43576-5 p. 31

- ^ Who do you say that I am? Essays on Christology by Jack Dean Kingsbury, Mark Allan Powell, David R. Bauer 1999 ISBN 0-664-25752-6 p. 106

- ^ a b New Testament christology by Frank J. Matera 1999 ISBN 0-664-25694-5 p. 67

- ^ The speeches in Acts: their content, context, and concerns by Marion L. Soards 1994 ISBN 0-664-25221-4 p. 34

- ^ a b c d Christology by Hans Schwarz 1998 ISBN 0-8028-4463-4 pp 132–134

- ^ Paul Haffner, 2004 The mystery of Mary Gracewing Press ISBN 0-85244-650-0 p. 17

- ^ Walter A. Elwell, Evangelical Dictionary of Theology, Second Edition (Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States: Baker Academic, 2001), p. 736.

- ^ Erwin Fahlbusch et al., "Mariology", The Encyclopedia of Christianity (Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States; Leiden, Netherlands: Wm. B. Eerdmans; Brill, 1999–2003), p. 409.

- ^ Communio, 1996, Volume 23, p. 175

- ^ Raymond Burke, 2008 Mariology: A Guide for Priests, Deacons, seminarians, and Consecrated Persons ISBN 1-57918-355-7 p. xxi

- ^ Theology for Today by Elmer L. Towns 2008 ISBN 0-15-516138-5 p. 173

- ^ "Angel of the Lord" by T. E. McComiskey in The Evangelical Dictionary of Theology 2001 ISBN 0-8010-2075-1 p. 62

Sources

[edit]- Printed sources

- Armentrout, Donald S.; Boak Slocum, Robert (2005), An Episcopal dictionary of the church, Church Publishing, ISBN 978-0-89869-211-2

- Baker, Mark D. (2006). Proclaiming the Scandal of the Cross: Contemporary Images of the Atonement. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4412-0627-5. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- Bauckham, R. (2011), Jesus: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press

- Beilby, James K.; Eddy, Paul R. (2009), The Nature of the Atonement: Four Views, InterVarsity Press

- Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando (2017). Feldt, Laura; Valk, Ülo (eds.). "The Process of Jesus' Deification and Cognitive Dissonance Theory". Numen. 64 (2–3). Leiden: Brill Publishers: 119–152. doi:10.1163/15685276-12341457. eISSN 1568-5276. ISSN 0029-5973. JSTOR 44505332. S2CID 148616605.

- Beversluis, Joel Diederik (2000), Sourcebook of the world's religions, New World Library, ISBN 978-1-57731-121-8

- Bird, Michael F.; Evans, Craig A.; Gathercole, Simon (2014), "Endnotes – Chapter 1", How God Became Jesus: The Real Origins of Belief in Jesus' Divine Nature – A Response to Bart Ehrman, Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-51961-4

- Bird, Michael F. (2017), Jesus the Eternal Son: Answering Adoptionist Christology, Wim. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Brown, Raymond Edward (2004), An Introduction to New Testament Christology, Paulist Press

- Chilton, Bruce. "The Son of Man: Who Was He?" Bible Review. August 1996, 35+.

- Cullmann, Oscar (1980). The Christology of the New Testament. trans. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-24351-7

- Davis, Leo Donald (1990), The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325–787): Their History and Theology (Theology and Life Series 21), Collegeville, MN: Michael Glazier/Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0-8146-5616-7

- Dunn, James D. G. (2003), Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1993), The Orthodox corruption of scripture: the effect of early Christological controversies on the text of the New Testament, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-510279-6, archived from the original on 14 December 2023, retrieved 16 October 2020

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2003), Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-972712-4, archived from the original on 14 December 2023, retrieved 27 February 2019

- Ehrman, Bart (2014), How Jesus became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee, Harper Collins

- Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. (2007), An introductory dictionary of theology and religious studies, Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0-8146-5856-7

- Fahlbusch, Erwin (1999), The encyclopedia of Christianity, Brill

- Fuller, Reginald H. (1965). The Foundations of New Testament Christology. New York: Scribners. ISBN 0-684-15532-X

- Greene, Colin J.D. (2004). Christology in Cultural Perspective: Marking Out the Horizons. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-2792-6

- Grillmeier, Alois (1975), "Jesus Christ: III. Christology", in Rahner, Karl (ed.), Encyclopedia of Theology: A Concise Sacramentum Mundi (reprint ed.), A&C Black, ISBN 9780860120063, retrieved 9 May 2016

- Grillmeier, Aloys; Bowden, John (1975), Christ in Christian Tradition: From the Apostolic Age to Chalcedon, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-22301-4

- Hodgson, Peter C. (1994). Winds of the Spirit: A Constructive Christian Theology. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (2016), Christology: A Global Introduction, Baker Academic

- Kingsbury, Jack Dean (1989). The Christology of Mark's Gospel. Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

- Letham, Robert. The Work of Christ. Contours of Christian Theology. Downer Grove: IVP, 1993, ISBN 0-8308-1532-5

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2017), The Origin of Divine Christology, vol. 169, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-108-19142-5

- Mack, Burton L. (1995), Who wrote the New Testament? The making of the Christian myth, Harper San Francisco, ISBN 978-0-06-065517-4

- McGrath, Alister E. (2006), Christianity: an introduction, Wiley, ISBN 978-1-4051-0901-7

- MacLeod, Donald (1998). The Person of Christ: Contours of Christian Theology. Downer Grove: IVP, ISBN 0-8308-1537-6

- McGrath, Alister E. (2007), Christian theology: an introduction, Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-5360-7, archived from the original on 14 December 2023, retrieved 16 October 2020

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450–680 A.D. The Church in history. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88-141056-3. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- Netland, Harold (2001), Encountering Religious Pluralism: The Challenge to Christian Faith & Mission, InterVarsity Press

- O'Collins, Gerald; Kendall, Daniel (1996), Focus on Jesus: Essays in Christology and Soteriology, Gracewing Publishing

- O'Collins, Gerald (2009), Christology: A Biblical, Historical, and Systematic Study of Jesus, OUP Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-955787-5

- Packer, J. I. (1973), What did the Cross Achieve? The Logic of Penal Substitution, Tyndale Biblical Theology Lecture

- Pannenberg, Wolfhart (1968), Jesus God and Man, Westminster John Knox Press, ISBN 978-0-664-24468-2

- Wolfhart Pannenberg, Systematic Theology, T & T Clark, 1994 Vol.2.

- Price, Richard; Gaddis, Michael (2006), The acts of the Council of Chalcedon, ISBN 978-0-85323-039-7

- Pugh, Ben (2015), Atonement Theories: A Way through the Maze, James Clarke & Co

- Rahner, Karl (2004), Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi, A&C Black, ISBN 978-0-86012-006-3

- Ramm, Bernard L. (1993), "Christology at the Center", An Evangelical Christology: Ecumenic and Historic, Regent College Publishing, ISBN 9781573830089

- Rausch, Thomas P. (2003), Who is Jesus? : an introduction to Christology, Liturgical Press, ISBN 978-0-8146-5078-3

- Schwarz, Hans (1998). Christology. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4463-4

- Talbert, Charles H. (2011), The Development of Christology during the First Hundred Years: and Other Essays on Early Christian Christology. Supplements to Novum Testamentum 140, Brill

- Taylor, Vincent (1956), The Cross of Christ, Macmillan & Co

- Weaver, J. Denny (2001), The Nonviolent Atonement, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Witherington, Ben (2009), "Christology – Paul's christology", in Hawthorne, Gerald F.; Martin, Ralph P.; Reid, Daniel G. (eds.), Dictionary of Paul and His Letters: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship, InterVarsity Press, ISBN 978-0-8308-7491-0

- Web-sources

- ^ a b c d e f "Christology | Definition, History, Doctrine, Summary, Importance, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "The Work of Jesus Christ: Summary".[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Lecture 8: The Work of Jesus Christ: Summary". Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ a b c d e "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Christology". www.newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Chabot, Eric (11 May 2009). "THINKAPOLOGETICS.COM: Jesus- A Functional or Ontological Christology?". THINKAPOLOGETICS.COM. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Collins English Dictionary, Complete & Unabridged 11th Edition, atonement Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 3 October 2012: "2. (often capital) Christian theol a. the reconciliation of man with God through the life, sufferings, and sacrificial death of Christ b. the sufferings and death of Christ"

- ^ a b "The Origin of "Divine Christology"?". Larry Hurtado's Blog. 9 October 2017. Archived from the original on 27 February 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Ehrman, Bart D. (14 February 2013). "Incarnation Christology, Angels, and Paul". The Bart Ehrman Blog. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ [Bart Ehrman (6 February 2013), "The Earliest Christology" Archived 28 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ""Early High Christology": A "Paradigm Shift"? "New Perspective"?". Larry Hurtado's Blog. 10 July 2015. Archived from the original on 1 March 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Bouma, Jeremy (27 March 2014). "The Early High Christology Club and Bart Ehrman – An Excerpt from 'How God Became Jesus'". Zondervan Academic Blog. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. Archived from the original on 21 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ "The Fifth Ecumenical Council – Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "The Sixth Ecumenical Council – Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "The Seventh Ecumenical Council – Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America". Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Jesus - The debate over Christology in modern Christian thought | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Mariology Is Christology", in Vittorio Messori, The Mary Hypothesis, Rome: 2005. [1] Archived 5 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

[edit]- Overview

- Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (2016), Christology: A Global Introduction, Baker Academic[ISBN missing]

- Reeves, Michael (2015). Rejoicing in Christ. IVP. ISBN 978-0830840229.

- Early high Christology

- Moehlman, Conrad Henry (1960), How Jesus Became God: An Historical Study of the Life of Jesus to the Age of Constantine, Philosophical Library

- Bird, Michael F. (2017), Jesus the Eternal Son: Answering Adoptionist Christology, Wim. B. Eerdmans Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8028-7506-8

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2003), Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0802860705, OCLC 51623141

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005), How on Earth did Jesus Become a God? Historical Questions about Earliest Devotion to Jesus, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0802828613, OCLC 61461917

- Bauckham, Richard (2008), Jesus and the God of Israel: God Crucified and Other Studies on the New Testament's Christology of Divine Identity, Eerdmans, ISBN 978-0-8028-4559-7

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2014), How Jesus became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee, Harper Collins

- Bird, Michael F.; Evans, Craig A.; Gathercole, Simon; Hill, Charles E.; Tilling, Chris (2014), How God Became Jesus: The Real Origins of Belief in Jesus' Divine Nature – A Response to Bart Ehrman, Zondervan, ISBN 978-0-310-51961-4

- Loke, Andrew Ter Ern (2017), The Origin of Divine Christology, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107199262

- Fletcher-Louis, Crispin (2015), Jesus Monotheism: Volume 1: Christological Origins: The Emerging Consensus and Beyond, Wipf and Stock Publishers, ISBN 978-1-7252-5622-4

- Atonement

- Pugh, Ben (2015), Atonement Theories: A Way through the Maze, James Clarke & Co[ISBN missing]