Freedom

| Part of a series on |

| Liberalism |

|---|

|

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".[1]

In one definition, something is "free" if it can change and is not constrained in its present state. Physicists and chemists use the word in this sense.[2] In its origin, the English word "freedom" relates etymologically to the word "friend".[2] Philosophy and religion sometimes associate it with free will, as an alternative to determinism or predestination.[3]

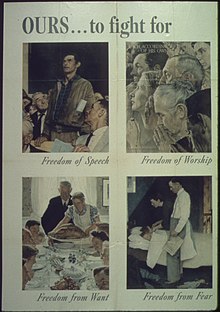

In modern liberal nations, freedom is considered a right, especially freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press.

Types

[edit]In political discourse, political freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy, and a distinction is made between countries that are free and dictatorships. In the area of civil rights, a strong distinction is made between freedom and slavery and there is conflict between people who think all races, religions, genders, and social classes should be equally free and people who think freedom is the exclusive right of certain groups. Frequently discussed are freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom of choice, and freedom of speech.

Liberty

[edit]Sometimes the terms "freedom" and "liberty" tend to be used interchangeably.[4][5] Sometimes subtle distinctions are made between "freedom" and "liberty"[6] John Stuart Mill, for example, differentiated liberty from freedom in that freedom is primarily, if not exclusively, the ability to do as one wills and what one has the power to do, whereas liberty concerns the absence of arbitrary restraints and takes into account the rights of all involved. As such, the exercise of liberty is subject to capability and limited by the rights of others.[7]

Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between "positive" freedom and "negative" freedom in his seminal 1958 lecture "Two concepts of liberty". Charles Taylor elaborates that negative liberty means an ability to do what one wants, without external obstacles and positive liberty is the ability to fulfill one's purposes.[8][9] Another way to describe negative liberty is freedom from limiting forces (such as freedom from fear, freedom from want, and freedom from discrimination), but descriptions of freedom and liberty generally do not invoke having liberty from anything.[5]

Wendy Hui Kyong Chun explains these differences in terms of their relation to institutions:

"Liberty is linked to human subjectivity; freedom is not. The Declaration of Independence, for example, describes men as having liberty and the nation as being free. Free will—the quality of being free from the control of fate or necessity—may first have been attributed to human will, but Newtonian physics attributes freedom—degrees of freedom, free bodies—to objects."[10]

"Freedom differs from liberty as control differs from discipline. Liberty, like discipline, is linked to institutions and political parties, whether liberal or libertarian; freedom is not. Although freedom can work for or against institutions, it is not bound to them—it travels through unofficial networks. To have liberty is to be liberated from something; to be free is to be self-determining, autonomous. Freedom can or cannot exist within a state of liberty: one can be liberated yet unfree, or free yet enslaved (Orlando Patterson has argued in Freedom: Freedom in the Making of Western Culture that freedom arose from the yearnings of slaves)."[10]

From domination

[edit]Freedom from domination was considered by Phillip Pettit, Quentin Skinner and John P. McCormick as a defining aspect of freedom.[11] While operative control is the ability to direct ones actions on a day-to-day basis, that freedom can depend on the whim of another, also known as reserve control. Phillip Petit and Jamie Susskind argues that both operative and reserve control are needed for democracy and freedom.[12][13]

See also

[edit]- Freedom Riders – civil-rights activists

- Freedom songs

- Freedom of thought

- Harm principle

- Internet freedom

Works[relevant?]

- Statue of Freedom, an 1863 sculpture by Thomas Crawford atop the dome of the US Capitol

- Miss Freedom, 1889 statue on the dome of the Georgia State Capitol (US)

- Freedom, 1985 statue by Alfred Tibor in Columbus, Ohio

- Freedom & Civilization, 1944 book by Bronislaw Malinowski about freedom from anthropological perspective

- Real Freedom, a term coined by political philosopher and economist Phillippe Van Parijs

References

[edit]- ^ Stevenson, Angus; Lindberg, Christine A., eds. (2010-01-01). "New Oxford American Dictionary". Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195392883.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-539288-3. Archived from the original on 2020-03-12. Retrieved 2023-06-02.[clarification needed]

- ^ a b "free". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F.; Monroe, Andrew E. (2014). "Recent Research on Free Will". Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol. 50. pp. 1–52. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-800284-1.00001-1. ISBN 978-0128002841.

- ^ See Bertrand Badie, Dirk Berg-Schlosser, Leonardo Morlino, International Encyclopedia of Political Science (2011), p. 1447: "Throughout this entry, incidentally, the terms freedom and liberty are used interchangeably".

- ^ a b Anna Wierzbicka, Understanding Cultures Through Their Key Words (1997), pp. 130–131: "Unfortunately... the English words freedom and liberty are used interchangeably. This is confusing because these two do not mean the same, and in fact what [Isaiah] Berlin calls "the notion of 'negative' freedom" has become largely incorporated in the word freedom, whereas the word liberty in its earlier meaning was much closer to the Latin libertas and in its current meaning reflects a different concept, which is a product of the Anglo-Saxon culture".

- ^ Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (2008), p. 9: "Although used interchangeably, freedom and liberty have significantly different etymologies and histories. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Old English frei (derived from Sanskrit) meant dear and described all those close or related to the head of the family (hence friends). Conversely in Latin, libertas denoted the legal state of freedom versus enslavement and was later extended to children (liberi), meaning literally the free members of the household. Those who are one's friends are free; those who are not are slaves".

- ^ Mill, John Stuart. [1859] 1869. On Liberty (4th ed.). London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. pp. 21–22 Archived 17 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (1985). "What's Wrong With Negative Liberty". Philosophical Papers: Volume 2, Philosophy and the Human Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 211–229. ISBN 978-0521317498. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah. Four Essays on Liberty. 1969.

- ^ a b Wendy Hui Kyong Chun, Control and Freedom: Power and Paranoia in the Age of Fiber Optics (2008), p. 9.

- ^ Springborg, Patricia (December 2001). "Republicanism, Freedom from Domination, and the Cambridge Contextual Historians". Political Studies. 49 (5): 851–876. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.00344. ISSN 0032-3217.

- ^ Pettit, Philip (2014). Just freedom: a moral compass for a complex world. The Norton global ethics series (First ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 2–3, 221. ISBN 978-0-393-06397-4.

- ^ Susskind, Jamie (2022). "Ch. 2". The digital republic: on freedom and democracy in the 21st century (1st ed.). New York London: Pegasus Books. ISBN 978-1-64313-901-2.

External links

[edit]- "Freedom", BBC Radio 4 discussion with John Keane, Bernard Williams & Annabel Brett (In Our Time, 4 July 2002)