Grass skirt

A grass skirt is a costume and garment made with layers of plant fibres such as grasses and leaves that is fastened at the waistline.[1][2]

Pacific

[edit]Grass skirts were introduced to Hawaii by immigrants from the Gilbert Islands around the 1870s to 1880s[3] although their origins are attributed to Samoa as well.[4][5] According to DeSoto Brown, a historian at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, it is likely Hawaiian dancers began wearing them during their performances on the vaudeville circuit of the United States mainland. Traditional Hawaiian skirts were often made with fresh ti leaves, which were not available in the United States. By the turn of the century, Hawaiian dancers in both Hawaii and the US were wearing grass skirts. Some Hawaiian-style hula dancers still wear them.[3] The traditional costume of Hawaiian hula kahiko includes kapa cloth skirts and men in malo (loincloth). However, during the 1880s hula ‘auana was developed from western influences. It is during this period that the grass skirt began to be seen everywhere although hula ‘auana costumes usually included more western looking clothing with fabric-topped dresses for women and pants for men.[6] The use of the grass skirt was present in the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago where Hawaiian hula dancers played into American stereotypes by wearing the costume.[7]

From the late 19th-century to World War II, grass skirts in Polynesia became a "powerful symbol of South Sea sexuality".[7][8] In the Pacific theater, grass skirts were sought after souvenirs by servicemen abroad.[9] The end of the war saw many sailors returning from their duties in the Pacific. Polynesian culture had begun to take root in the US through such things as James A. Michener's Tales of the South Pacific and its subsequent musical and film adaption, as well as Don the Beachcomber opening in Hollywood. The war had helped to create a national interest in Polynesian food and décor.[10][11] The tiki culture continued, spurred on by Hawaii's statehood in 1959 and Disney's opening of the Enchanted Tiki Room in 1963 as well as popular film and television shows like "Hawaiian Eye" in 1959 and Elvis Presley's Blue Hawaii in 1961.[10][11]

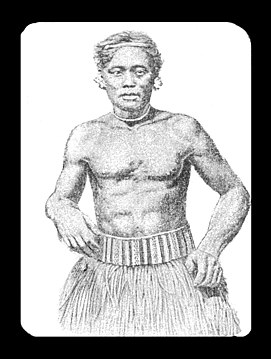

In Fijian culture, both women and men traditionally wore skirts called the liku made from hibiscus or root fibers and grass.[12][13] In Māori culture there is a skirt-like garment made up of numerous strands of prepared flax fibres, woven or plaited, known as a piupiu which is worn during Māori cultural dance.[14] In Nauru culture the native dress of both sexes consists of a ridi, a bushy skirt composed of thin strips of pandanus palm-leaf that can be both short, knee- and foot-long.[15][16][17] In Tonga, the grass skirt was known as a sisi pueka and was worn in dance performances.[9]

Africa

[edit]The Sotho people traditionally wore grass skirts called the mosotho.[18]

Gallery

[edit]-

Kini Kapahu Wilson and fellow hula dancer wearing grass skirts at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago[7][19]

-

South sea islander wearing a liku

-

Maori cultural group performing, wearing piupiu c. 1943

-

See also

[edit]- Kiekie, from Tonga

References

[edit]- ^ Oxford University 2011, p. 1342.

- ^ Picken 2013, p. 153.

- ^ a b McAvoy, Audrey (October 14, 2012). "Hawaii takes aim at inauthentic island icons". Honolulu. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- ^ Clark, Sydney (1939). Hawaii with Sydney A. Clark. Prentice-Hall, Incorporated. p. 129.

- ^ Hopkins, Jerry (January 1982). The hula. Apa Productions (HK). p. 181. ISBN 9789971925079.

- ^ "A Hip Tradition". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ a b c Hix 2017.

- ^ Brawley & Dixon 2012, p. 114.

- ^ a b Bennett, Judith A. (2009). Natives and Exotics: World War II and Environment in the Southern Pacific. University of Hawaii Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-8248-3265-0.

- ^ a b Starr 2011, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b Lukas 2016, p. 141.

- ^ Me, Rondo B. B. (2004). Fiji Masi: An Ancient Art in the New Millennium. Catherine Spicer and Rondo B.B. Me. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-646-43762-0.

- ^ Bishop Museum Handbook. Bishop Museum Press. 1915. p. 48.

- ^ Fashion: The Ultimate Book of Costume and Style. Dorling Kindersley Limited. 2012. p. 463. ISBN 978-1-4093-2241-2. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ O'Connor, T.P. (1927). T.P.'s and Cassell's Weekly. Cassell. p. 173. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Association, I.L.; Leprosy, L.W.M.E. (1952). International Journal of Leprosy ... International Leprosy Association. p. 13. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Viviani, N. (1970). Nauru, phosphate and political progress. University of Hawaii Press. p. 6. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- ^ Hammond-Tooke, W. D. (1981). Boundaries and Belief: The Structure of a Sotho Worldview. Witwatersrand University Press. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-85494-659-4.

- ^ Hoverson, Martha. "Hawaii at the Fair". Chinese in Northwest America Research Committee. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

Sources

[edit]- Brawley, S.; Dixon, C. (2012), Hollywood's South Seas and the Pacific War: Searching for Dorothy Lamour, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 114, ISBN 978-1-137-09067-6

- Hix, Lisa (2017), "How America's Obsession With Hula Girls Almost Wrecked Hawaiʻi", Collectors Weekly, retrieved May 18, 2017

- Lukas, Scott A. (2016), A Reader In Themed and Immersive Spaces, Lulu.com, ISBN 978-1-365-38774-6, OCLC 1004748897[permanent dead link]

- Oxford University, Press (11 July 2011), Complete Oxford Dictionary 11: Complete Oxford Dictionary 11, Oxford University Press, p. 1342, GGKEY:3XX5FQGNP71[permanent dead link]

- Picken, Mary Brooks (24 July 2013), A Dictionary of Costume and Fashion: Historic and Modern, Courier Corporation, p. 153, ISBN 978-0-486-14160-2

- Starr, Kevin (2011), Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950–1963, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-992430-1, OCLC 261177770

![Kini Kapahu Wilson and fellow hula dancer wearing grass skirts at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago[7][19]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Kini_Kapahu_and_her_fellow_hula_dancer_at_the_Midway_Plaisance_at_the_World%E2%80%99s_Columbian_Exhibition%2C_Chicago%2C_1893.jpg/290px-Kini_Kapahu_and_her_fellow_hula_dancer_at_the_Midway_Plaisance_at_the_World%E2%80%99s_Columbian_Exhibition%2C_Chicago%2C_1893.jpg)