Hugh Courtenay (died 1471)

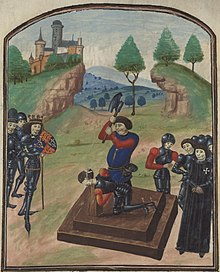

Sir Hugh Courtenay (c. 1427 – 6 May 1471) of Boconnoc in Cornwall, was twice a Member of Parliament for Cornwall in 1446–47 and 1449–50.[1] He was beheaded after the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471,[1] together with John Courtenay, 7th Earl of Devon (d. 1471), the grandson of his first cousin the 4th Earl, and last in the senior line, whose titles were forfeited. His son Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (d. 1509), was created Earl of Devon in 1485 by King Henry VII, following the Battle of Bosworth and the closure of the Wars of the Roses.

Origins

[edit]

He was the second son of Sir Hugh Courtenay (c. 1358 – 1425), of Haccombe and Bampton, Devon, MP and Sheriff of Devon (a grandson of Hugh de Courtenay, 2nd/10th Earl of Devon (1303–1377) and the younger brother of Edward de Courtenay, 3rd/11th Earl of Devon (1357–1419), "The Blind Earl"),[1] by his fourth wife Maud Beaumont (d. 3 July 1467), daughter of Sir William Beaumont of Shirwell, in Devon, by Isabel Willington, daughter of Sir Henry Willington of Umberleigh, in Devon.

Battle of Tewkesbury

[edit]

Courtenay's presence at the Battle of Tewkesbury, fighting for the Lancastrian cause, is narrated by Cleaveland (1735)[2] as follows:[3]

In 1471, 11th Edward IV, on Easter day Queen Margaret wife of Henry VI and her son Prince Edward landed at Weymouth, and went from thence to an abbey near called Cerne, and while they were there Edmund, Earl of Somerset, John, Earl of Devonshire, and many others came unto them, and welcomed them to England. And the Earl of Devonshire the more to encourage the western counties to join with them repaired to Exeter, where they sent for this Sir Hugh Courtenay of Boconnock and many others, and having joined the Queen marched with her to Tewksbury where was fought a bloody battle May 4th 1471. And so it was in a little time Prince Edward's army was put to flight, and the Duke of Somerset and many others fled for sanctuary to Tewksbury Church, and in a day or two after were taken out and beheaded, but whether Sir Hugh Courtenay died in battle, or was amongst those who took sanctuary, it is not said, but it is highly probable that he was killed at the time, either in the field or afterwards and was buried at Tewksbury.

Marriage and children

[edit]

He married Margaret Carminow, a daughter and co-heiress of Thomas Carminow of Boconnoc, by his wife Joan Hill, a daughter of Robert Hill. They had the following issue:[1]

Sons

[edit]- Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (d. 1509), created Earl of Devon in 1485 by King Henry VII, the title long held by his ancestors and cousins but forfeited during the Wars of the Roses. His great-grandson was Edward Courtenay, 1st Earl of Devon (d. 1556), who died unmarried and without children, the last of the mediaeval Courtenay Earls of Devon seated at Tiverton Castle, whose co-heirs were the descendants of Sir Hugh Courtenay's four daughters below.

- Sir Walter Courtenay, died childless

- John Courtenay (d. 1509), died childless

Daughters

[edit]- Elizabeth/Isabel Courtenay, wife of John Trethurffe of Trethurffe in the parish of Ladock, near Truro, Cornwall.[4]

- Maud Courtenay, wife of John Arundell of Talvern

- Isabel/Elizabeth Courtenay, wife of William Mohun[5] of Hall in the parish of Lanteglos-by-Fowey in Cornwall, a descendant of John Mohun (d. 1322[6]) of Dunster Castle in Somerset, feudal baron of Dunster by his wife Anne Tiptoft.[7] In 1628 her descendant John Mohun (1595–1641) was created by King Charles I Baron Mohun of Okehampton,[8] his ancestor having inherited as his share Okehampton Castle and remnants of the feudal barony of Okehampton, one of the earliest possessions of the Courtenays. The Mohuns held the manor of Boconnoc not (as might be expected) as a share of the Courtenay inheritance, but by lease from the Russell Earl of Bedford.[9]

- Florence Courtenay, wife of John Trelawny

Death, burial and monument

[edit]Having died on 6 May 1471 during the Battle of Tewkesbury, he is said by Cleveland to have been buried in Tewkesbury Priory. He and his wife are said by Rogers (1877)[10] and by Hoskins (1954),[11] to be represented by the surviving effigies[12] in the canopied tomb in the south aisle of Ashwater Church in Devon, which displays the arms of Courtenay and Carminowe,[13] although the manor of Ashwater descended from Carminowe to the Carew family, not to Courtenay.[14] Pevsner (2004) on the other hand suggests that the effigy is that of Thomas Carminow (d. 1442), and states the monument to be "the most ambitious late mediaeval monument in north-west Devon", with the design of the canopy based on those of Bishop Stafford and Bishop Branscombe in Exeter Cathedral.[15]

Concerning the heraldry in Ashwater Church, Rogers states:[16]

In the east window of the aisle of Ashwater Church, in which the effigies occur, are the arms of Carew impaling Carminow ; and on a similar shield the dexter impalement of which is now blank (but was doubtless originally filled by the arms of Carminow), impaling, quarterly Courtenay and De Redvers, thus indicating that both heiresses Joan and Margaret Carminow contributed to the rebuilding of the aisle. The arms of Carminow impaling Courtenay are found also in Wolborough Church, marshalled as at Ashwater, together with the arms of Sir Hugh of Haccombe, his father, and his three wives.

Eventual co-heirs

[edit]Thus the Courtenay estates were divided into four parts.[5] On the death of Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon, in 1556, the actual heirs to his estates were the following descendants of the four sisters above:[17]

- Reginald Mohun (1507/8–67) of Hall in the parish of Lanteglos-by-Fowey in Cornwall, who inherited Okehampton Castle;

- Margaret Buller;

- John Vivian;

- John Trelawny.

Sources

[edit]- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620, Exeter, 1895, pedigree of Courtenay, p. 245

- The National Archives: C 2/Eliz/W13/36, Winslade versus Arundell.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Vivian, p.245

- ^ Ezra Cleaveland (Rector of Honiton in Devon), Genealogical History of the Noble and Illustrious Family of Courtenay, Exeter, 1735 [1]

- ^ Quoted in William Henry Hamilton Rogers, The Antient Sepulchral Effigies and Monumental and Memorial Sculpture of Devon, Exeter, 1877, p.340 [2]

- ^ Image of surviving part of mansion house

- ^ a b Lysons, Daniel & Samuel, Magna Britannia, Vol 6, Devonshire, 1822, pp.496–520

- ^ Vivian, 1895, p.565

- ^ Vivian, Heraldic Visitations of Devon, pp.245, 565, 566, where she is called "Elizabeth", frequently interchangeable with "Isabel"[3] Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pole, Sir William (d.1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.11

- ^ "MOHUN, Reginald I (1507/8-67), of Hall and Boconnoc, Cornw. | History of Parliament Online".

- ^ Rogers, William Henry Hamilton, The Antient Sepulchral Effigies and Monumental and Memorial Sculpture of Devon, Exeter, 1877, p.339 [4]

- ^ Hoskins, W. G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p.323

- ^ See image

- ^ Rogers, pp.339-40

- ^ Pole, Sir William (d. 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791, p.352

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.138

- ^ Rogers, p.341

- ^ History of Parliament biography of Reginald Mohun (1507/8-67) of Hall [5]