Howard Hughes Medical Institute

| Founded | 1953 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Howard Hughes |

| Focus | Biological and Medical research and Science Education |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 38°59′55″N 77°4′47″W / 38.99861°N 77.07972°W |

| Method | Laboratories, Funding |

Key people |

|

Revenue (2022) | -US$2.303 billion[1] (due to losses on investments) |

| Expenses (2022) | US$853 million[1] |

| Endowment | US$24 billion[1] |

| Employees | 2,300 (2022)[2] |

| Website | hhmi.org |

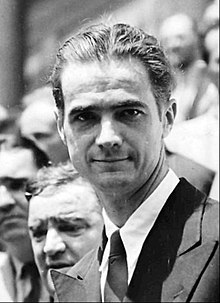

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) is an American non-profit medical research organization based in Chevy Chase, Maryland.[3][4] It was founded in 1953 by Howard Hughes, an American business magnate, investor, record-setting pilot, engineer,[5] film director, and philanthropist, known during his lifetime as one of the most financially successful individuals in the world. It is one of the largest private funding organizations for biological and medical research in the United States. HHMI spends about $1 million per HHMI Investigator per year, which amounts to annual investment in biomedical research of about $825 million.

The institute has an endowment of $22.6 billion, making it the second-wealthiest philanthropic organization in the United States and the second-best-endowed medical research foundation in the world.[6] HHMI is the former owner of the Hughes Aircraft Company, an American aerospace firm that was divested to various firms over time.

History

[edit]

The institute was formed with the goal of basic research including trying to understand, in Hughes's words, "the genesis of life itself." Despite its principles, in the early days it was generally viewed as a tax haven for Hughes's huge personal fortune. Hughes was HHMI's sole trustee and he transferred his stock of Hughes Aircraft to the institute, in effect turning the large defense contractor into a tax-exempt charity. For many years the Institute grappled with maintaining its non-profit status; the Internal Revenue Service challenged its "charitable" status which made it tax exempt. Partly in response to such claims, starting in the late 1950s it began funding 47 investigators doing research at eight different institutions; however, it remained a modest enterprise for several decades.[citation needed]

The institute was initially located in Miami, Florida, in 1953. Hughes's internist, Verne Mason, who treated Hughes after his 1946 plane crash, was chairman of the institute's medical advisory committee.[7] By 1975, Hughes was sole trustee of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, which in turn owned all the stock of the Hughes Aircraft Company.[8]

In 1969, Representative Wright Patman "complained that the Hughes foundation was a tax‐evasion device," noting that the institute spent only $5.7 million for its operations between 1954 and 1961, a period during which Hughes Aircraft accumulated $76.9 million in profits. By 1975, it had also avoided certain stipulations of the 1969 reform act for charitable institutions due to legal filings by Hughes to change its operational status, with his objections going directly to the White House.[9]

The institute moved to Coconut Grove, Florida, in the mid-1970s and then to Bethesda, Maryland, in 1976.[10]

In 1993, the institute moved to its headquarters in Chevy Chase, Maryland.[11]

It was not until after Hughes's death in 1976 that the institute's profile increased from an annual budget of $4 million in 1975 to $15 million in 1978 and prior to Hughes Aircraft sale the number had peaked to $200 million per year. At the time of the sale Hughes Aircraft employed 75,000 people and vast amounts of money from the approximate annual revenue of $6 billion were put into Hughes Aircraft internal research and development rather than the medical institute. Most of the money for the medical institute came from the operations at Ground System Group responsible for providing Air Defense Systems to NATO, Pacific Rim, and the USA. In this period it focused its mission on genetics, immunology, and molecular biology. Since Hughes died without a will as the sole trustee of the HHMI, the institute was involved in lengthy court proceedings to determine whether it would benefit from Hughes's fortune. In April 1984, a court appointed new trustees for the institute's holdings.[12]

In January 1985 the trustees announced they would sell Hughes Aircraft by private sale or public stock offering. On June 5, 1985 General Motors (GM) was announced as the winner of a secretive five-month, sealed-bid auction. The purchase was completed on December 20, 1985, for an estimated $5.2 billion, $2.7 billion in cash and the rest in 50 million shares of GM Class H stock. The proceeds caused the institute to grow dramatically.

HHMI completed the building of a new research campus in Ashburn, Virginia called Janelia Research Campus in October 2006. It is modeled after AT&T's Bell Labs and the Medical Research Council's Laboratory of Molecular Biology. With a main laboratory building nearly 1,000 feet (300 m) long, it contains 760,000 square feet (71,000 m2) of enclosed space, used primarily for research. The campus also features apartments for visiting researchers.

In 2007, HHMI and the publisher Elsevier announced they have established an agreement to make author manuscripts of HHMI research articles published in Elsevier and Cell Press journals publicly available six months following final publication. The agreement takes effect for articles published after September 1, 2007.

In 2008, the Trustees of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute selected Robert Tjian as the new president of HHMI.

In 2009, HHMI awarded fifty researchers, as part of the HHMI Early Career Scientist Competition.[citation needed]

In 2014, the institute created a new round of its primary award competition, for a total of $150 million in award money from 2015 to 2012.[13] The institute is expanding the Ashburn campus in 2019.[14]

In 2016, the HHMI Trustees selected Erin K. O'Shea, a previous Vice President and Chief Scientific Officer at the institute, the new president of HHMI.[15]

In 2022, HHMI began to require immediate open access to publications from its research.[16]

In 2023, HHMI was sued by Dr. Vivian Cheung for disability discrimination.[17]

Assets

[edit]As of 2017[update] the Howard Hughes Medical Institute had assets of $22,588,928,000.[1]

Funding details

[edit]| Funding details as of 2017[update]:[1] | Revenue and support as of 2017: $2,382,777,000 Interest, dividends, and other income from investments (8.1%) Realized gains on investment and derivative contracts, net (52.7%) Change in unrealized gains/(losses) of investments and derivative contracts (39.2%)

|

Expenses as of 2017: $936,514,000 Medical research (70.4%) Science education and other scientific programs (12.8%) General and administrative (9.8%) Interest expense (7.0%)

|

See also

[edit]References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Howard Hughes Medical Institute" (PDF). Howard Hughes Medical Institute. 17 November 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 April 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "Press Room | HHMI". www.hhmi.org. Archived from the original on 2024-07-05. Retrieved 2024-07-01.

- ^ "Chevy Chase CDP, Maryland Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine." U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved on March 12, 2010.

- ^ "Contact Archived 2013-06-21 at the Wayback Machine." Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Retrieved on March 12, 2010.

- ^ "Howard R. Hughes | Howard R. Hughes College of Engineering | University of Nevada, Las Vegas". www.unlv.edu. 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2020-01-01. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ^ "Howard Hughes Medical Institute | 2013 Year in Review". Archived from the original on August 22, 2014.

- ^ Dr. Verne Mason. Miami Physician. Howard Hughes aide dies. Also treated Pershing. The New York Times. November 17, 1965.

- ^ Dietrich, Noah; Thomas, Bob (1972). Howard, The Amazing Mr. Hughes. Greenwich: Fawcett Publications, Inc. p. 268.

- ^ "Howard Hughes, beyond the law", The New York Times, Sep 14, 1975, archived from the original on January 4, 2019, retrieved January 3, 2019

- ^ Wernick, Ellen D. "Howard Hughes Medical Institute". Answers.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-07. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ^ "Howard Hughes Medical Institute History". Funding Universe. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- ^ Note: the original trustees were: Helen K. Copley, Donald S. Fredrickson, M.D., Frank William Gay, James H. Gilliam, Jr., Esq., Hanna H. Gray, Ph.D., William R. Lummis, Esq., Irving S. Shapiro, Esq., George W. Thorn, M.D.

- ^ "Howard Hughes Medical Institute Offers $150-Million in New Awards", The Chronicle of Higher Education, Jan 15, 2014, archived from the original on January 4, 2019, retrieved January 3, 2019

- ^ "Howard Hughes Medical Institute to expand Loudoun research campus", Washington Business Journal, Jan 3, 2019

- ^ "The week in science: 5–11 February 2016". Nature. 530 (7589). People: HHMI president. February 10, 2016. Bibcode:2016Natur.530..134.. doi:10.1038/530134a.

- ^ "HHMI, one of the largest research philanthropies, will require immediate open access to papers". AAAS. Oct 1, 2020. Archived from the original on March 7, 2023. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ Wadman, Meredith (December 4, 2023). "Trial puts Howard Hughes Medical Institute—and disabled scientists—in the spotlight". Science. Retrieved 5 July 2024.