Ralph Hotere

Ralph Hotere | |

|---|---|

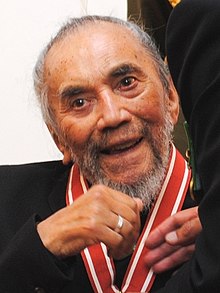

Hotere in 2012 | |

| Born | Hone Papita Raukura Hotere 11 August 1931 |

| Died | 24 February 2013 (aged 81) |

| Education | Hato Petera College, Auckland Teachers' Training College, Dunedin School of Art, part of King Edward Technical College |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Black Phoenix, Jerusalem, Jerusalem, This might be a double cross jack |

| Spouses | |

| Awards | Order of New Zealand, honorary doctorate from the University of Otago, Icon Award from the Arts Foundation of New Zealand |

Hone Papita Raukura "Ralph" Hotere ONZ (11 August 1931 – 24 February 2013)[1] was a New Zealand artist. He was born in Mitimiti, Northland and is widely regarded as one of New Zealand's most important artists. In 1994 he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Otago and in 2003 received an Icon Award from the Arts Foundation of New Zealand.

In the 2012 New Year Honours, Hotere was appointed to the Order of New Zealand for services to New Zealand.[2][3]

Early history

[edit]Hotere was born in Mitimiti, close to the Hokianga Harbour in the Northland Region, one of 15 children.[4] When Hotere was 9, his older brother Jack enlisted in the army. Jack was killed in action in Italy in 1943.

Hotere received his secondary education at Hato Petera College, Auckland, where he studied from 1946 to 1949. After early art training at the Auckland Teachers' Training College under the tutelage of J. D. Charlton Edgar,[4] he moved to Dunedin in 1952, where he studied at Dunedin School of Art, part of King Edward Technical College. During the later 1950s, he worked as a schools art advisor for the Education Department in the Bay of Islands.

In 1961 Hotere gained a New Zealand Art Societies Fellowship and travelled to England where he studied at the Central School of Art and Design in London. During 1962–1964 he studied in France and travelled around Europe, during which time he witnessed the development of the Pop Art and Op Art movements.[citation needed] His travels took him, among other places, to the war cemetery in Italy where his brother was buried. This event, and the politics of Europe during the 1960s, had a profound effect on Hotere's work, notably in the Sangro series of paintings.[5]

Return to New Zealand

[edit]

Hotere returned to New Zealand and exhibited in Dunedin in 1965, and returned to the city in 1969 when he became the University of Otago's Frances Hodgkins Fellow. At about that time he began to introduce literary elements to his work. He worked with poets such as Hone Tuwhare and Bill Manhire to produce several strong paintings, and produced other works specifically for the New Zealand literary journal Landfall. Hotere also worked in collaboration with other prominent artists, notably Bill Culbert.[4] Hotere moved to Carey's Bay in Port Chalmers in 1969, spending most of his life in the town.[5]

From the 1970s onward, Hotere was noted for his use of unusual tools and materials in creating his work, notably the use of power tools on corrugated iron and steel within the context of two-dimensional art.[citation needed]

Black paintings

[edit]

From 1968,[4] Hotere began the series of works with which he is perhaps best known, the Black Paintings. In these works, black is used almost exclusively. In some works, strips of colour are placed against stark black backgrounds in a style reminiscent of Barnett Newman. In other black paintings, stark simple crosses appear in the gloom, black on black. Though minimalist, the works, as with those of most good abstractionists, have a redolent poetry of their own. The simple markings speak of transcendence, of religion, or peace.[citation needed]

Black Phoenix

[edit]The themes of the black paintings extended to later works, notably the colossal Black Phoenix (1984–88), constructed out of the burnt remains of a fishing boat.[6] This major installation incorporates the prow of the boat flanked by burnt planks of wood. Other planks form a pathway leading the prow. Each plank has had a strip laid bare to reveal the natural wood underneath beneath. Several of the boards are inscribed with a traditional Maori proverb, Ka hinga atu he tete-kura haramai he tete-kura ("As one fern frond (person) dies - one is born to take its place").[6] A slight change has been made in the wording of the proverb, replacing haramai (transfer, pass over) to ara mai (the path forward), possibly indicating the cleared pathway of bare wood in front of the boat's burnt prow. The work measures 5m by 13m by 5.5m.[6]

Political art

[edit]

Politics were entwined in the subject matter of Hotere's art from an early stage. Hotere's Polaris series was a response to the 1984 threat of nuclear warheads due to the Polaris programme.[5] When Aramoana, a wetland near his Port Chalmers home, was proposed as the site for an aluminium smelter, Hotere was vocal in his opposition, and produced the Aramoana series of paintings.[5] Similarly, he produced series protesting against a controversial rugby tour by New Zealand of apartheid-era South Africa (Black Union Jack) in 1981, and the sinking of the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior (Black rainbow) in 1985. Later, his reactions to Middle East politics resulted in works such as Jerusalem, Jerusalem and This might be a double cross jack.[citation needed]

Later life

[edit]In 1992, Hotere transformed the RKS Gallery in Wellington with an exhibition utilising kilometres of number 8 wire.[5]

Hotere's work was slowed by a stroke in 2001, but he continued to create and exhibit regularly until his death in February 2013.[7]

A documentary film of the artist's life and work, Hotere, was released by Paradise Films in 2001, in association with Creative New Zealand and the New Zealand Film Commission.[8] Written and directed by Merata Mita, the documentary made its overseas debut at the 2002 Sundance Film Festival.[9]

Selected works

[edit]- Still Life 1959 view

- Cruciform II from the Human Rights series 1964 view

- Red on White 1965 view

- Red on Black 1969 view

- Black Painting IIIa: From 'Malady', a poem by Bill Manhire 1970 view

- Black Window - Towards Aramoana 1981 view

- Untitled 1981 view

- Land of the Wrong White Crowd 1981 view

- Aramoana Nineteen Eighty Four 1984 view

- Blackwater 1998-1999 view

- Black Painting 1985-1986 view

- Dawn/Water Poem 1986 view

- Black Cerulean 1999 view

Personal life

[edit]Hotere was of Māori descent (Te Aupōuri and Te Rarawa).[6]

He married three times, with two of his wives also being artists. His second wife was artist and poet Cilla McQueen, whom he married in 1973, and with whom he moved to Careys Bay near Port Chalmers in 1974. The two separated amicably during the 1990s.[4] Hotere later married Mary McFarlane, another notable artist, in February 2002.[10]

Hotere died on 24 February 2013, aged 81 and was survived by his daughter Andrea, three mokopuna (grandchildren) and also his third wife Mary.[7] He was buried at Mitimiti.

Hotere Garden Oputae

[edit]Hotere's former studio was on land at the tip of Observation Point, the large bluff overlooking the Port Chalmers container terminal. When the port's facilities were expanded, part of the bluff was removed, including the area of Hotere's studio (after strenuous objection from many of the town's residents). Part of the bluff close to the removed portion is now an award-winning sculpture garden, the Hotere Garden Oputae, organised in 2005 by Hotere and featuring works by both him and by other noted New Zealand modern sculptors.[11] Other sculptors with work in the garden include Russell Moses, Shona Rapira Davies, and Chris Booth.[12]

References

[edit]- ^ "Ralph Hotere". Auckland Art Gallery. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- ^ "New Year Honours 2012" (27 January 2012) 8 The New Zealand Gazette 215.

- ^ "Prominent artist tops New Year honours (+ list)". The New Zealand Herald. APNZ. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Entwisle, Peter (2 March 2013). "Never lost ability to surprise the public". Otago Daily Times. p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Caughey, Elizabeth; Gow, John (1997). Contemporary New Zealand Art 1. Everbest Printing. pp. 8–13. ISBN 1-86953-218-X.

- ^ a b c d e Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (2005). Treasures from the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. 79: Te Papa Press. ISBN 1-877385-12-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b "Artist Ralph Hotere has died". The New Zealand Herald. 24 February 2013.

- ^ Hotere at IMDb

- ^ Mark Deming (24 February 2013). "Hotere (2002)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- ^ Cook, M. "Dunedin artists confirm February wedding," Otago Daily Times, 11 May 2002, p. 2

- ^ "Design award for Hotere garden." Otago Daily Times, 20 August 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Jeffery, Joshua, "Hotere Garden Oputae," Insiders Dunedin, 18 March 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

External links

[edit]- Works at Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

- Works at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki: Works by Ralph Hotere

- Major overview from Art New Zealand magazine

- New Zealand Arts Foundation biography

- Biography from John Leech Gallery

- Reproduction print of Ralph Hotere painting

- Review of 2004 exhibition from New Zealand Listener magazine

- 1931 births

- 2013 deaths

- People educated at Hato Petera College, Auckland

- Members of the Order of New Zealand

- New Zealand modern painters

- New Zealand Māori artists

- People from Port Chalmers

- People from the Hokianga

- Te Aupōuri people

- Te Rarawa people

- Alumni of the Central School of Art and Design

- 20th-century New Zealand artists

- 20th-century New Zealand male artists