H. L. Gold

H. L. Gold | |

|---|---|

| Born | Horace Leonard Gold April 26, 1914 Montreal, Quebec, Canada |

| Died | February 21, 1996 (aged 81) Laguna Hills, California, U.S. |

| Pen name | Clyde Crane Campbell, Dudley Dell, Leigh Keith, Richard Storey |

| Occupation |

|

| Genre | Science fiction, Fantasy |

| Notable works | "Trouble with Water", "The Old Die Rich" |

| Spouse | Evelyn Stein (1939–1957; divorced) Muriel "Nicky" (Nicholson) Conley (1965–his death) |

Horace Leonard Gold (April 26, 1914 – February 21, 1996) was an American science fiction writer and editor. Born in Canada, Gold moved to the United States at the age of two. He was most noted for bringing an innovative and fresh approach to science fiction while he was the editor of Galaxy Science Fiction, and also wrote briefly for DC Comics.

Life and family

[edit]H. L. Gold was born on April 26, 1914 in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Gold was born Jewish, and there are claims that he at first had to write under pseudonyms because publishers feared the readers' potential antisemitism. He was drafted into the United States Army during World War II, serving in the Pacific War. As a result of trauma during his wartime experiences, he developed agoraphobia which became so severe that for more than two decades he was unable to leave his apartment. Towards the end of his life, he acquired some control over the condition.[1]

His marriage to Evelyn Stein ended in divorce in 1957, and his second marriage was to Muriel "Nicky" (Nicholson) Conley. He died in 1996.

His brother Floyd C. Gold, writing under the pen name Floyd C. Gale, was the primary book reviewer for Galaxy from 1955 to 1963. His son E. J. Gold is an artist, writer, and musician.

Author and editor

[edit]Science fiction

[edit]After becoming editor of Galaxy Gold wrote that as a "dazzled boy" he "discovered science fiction in 1927, at the age of 13":[2]

Amazing Stories had been out for a year then, but it was Wells' War of the Worlds, sitting innocently on a Providence library shelf, that I found first. The personal impact was that of an explosive harpoon, and when I belatedly discovered those beautifully garish Paul covers, decorated with heroically paralyzed men in jodhpurs and simperingly paralyzed women in blowy veils, among giant insects and plants with leering heads, I was hooked.[2]

During the 1930s, Gold unsuccessfully wrote stories for pulp magazines. The day he was fired from his regular job because his boss believed that a writer should not work as a busboy, Gold learned that he had made his first sale.[3] Beginning with "Inflexure" (as Clyde Crane Campbell) in Astounding Science Fiction (October 1934), Gold later worked for Standard Magazines, Fawcett Comics and Timely Comics.[4] He used the Campbell pen-name for his first half-dozen or so stories in 1934/35. When he resumed his writing career in 1938 he took the billing Horace L. Gold, but soon shortened it to the now more familiar H. L. Gold.

Gold's most noted stories tended more toward fantasy, like his "Trouble with Water" (Unknown, March 1939). In 1939–41 he was an assistant editor on a trio of science fiction magazines – Captain Future, Thrilling Wonder Stories and Startling Stories. His 1939 novel, None But Lucifer in Unknown (September 1939) was a collaboration with L. Sprague de Camp.

Comics and World War II

[edit]During the early 1940s, Gold teamed with Kendell Foster Crossen on comic book scripts, freelancing with DC Comics writing for Batman, Superman, Superboy, Boy Commandos and Wonder Woman from "roughly the end of 1942" until World War II interrupted his career.[4] He was drafted in 1944, although he was Canadian, flatfooted, overage and had a newborn child. He returned on compassionate leave (possibly in May 1946[4]) to be at his dying father Henry's bedside in Fall River, Massachusetts. He had been offered directorship of Armed Forces Radio postwar, which he declined. After serving, he returned to New York City, where he scripted for comic books and radio programs. Gold's story "The Old Die Rich" (Galaxy Science Fiction, March 1953), written at the same time as Marcia Davenport's My Brother's Keeper, may have been inspired by the New York Times articles about the Collyer brothers as was Davenport's novel. Gold often found story ideas in newspaper clippings.

Galaxy and Beyond

[edit]

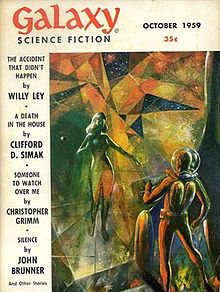

H. L. Gold is perhaps best known as a leading magazine editor during the American post-World War II science fiction boom. In 1949 he began in that direction, and launched Galaxy Science Fiction in 1950, which was soon followed by its companion fantasy magazine, Beyond Fantasy Fiction (1953–55).

Gold's Galaxy "made a startling impact on the world of science fiction", successor Frederik Pohl said in 1965, with "wit and relevance"; "It is difficult to exaggerate that impact". Some writers saw Gold as "a sort of slave-driver" but, Pohl said, "as one of the most frequently flogged of the slaves ... the results were worth it".[5][6] With Galaxy Gold created a different kind of science fiction magazine by focusing less on technology, hardware and pulp adventures. Instead, he introduced themes leaning toward sociology, psychology and satire. He paid more than was common at the time and had the advantage that several talented authors had become alienated from John W. Campbell due to his enthusiasm for Dianetics.

Gold also edited several anthologies (1952–62) related to the magazine. He suffered from increasing agoraphobia (originating from war trauma), and retired from Galaxy in 1961 due to his health problems.[4] Gold lived the rest of his life in seclusion, though he published occasional short stories and guest editorials through the early 1980s.

Collected stories

[edit]His collection The Old Die Rich (Crown, 1955) includes "And Three to Get Ready", "At the Post", "The Biography Project" (as Dudley Dell), "Don't Take It to Heart", "Hero", "Love in the Dark" (also known as "Love Ethereal"), "Man of Parts", "The Man with English", "No Charge for Alterations", "The Old Die Rich", "Problem in Murder" and "Trouble with Water". While Anthony Boucher praised Gold as "almost the only s.f. writer capable of creating lower and lower-middle class background," he found that the stories "are simply not up to the standards of craftsmanship" that Gold set as an editor.[7]

Awards

[edit]- 1953 – Hugo for Best Prozine Editor

- 1975 – Westercon Life Achievement Award

- 1987 – Milford Award

Bibliography

[edit]Short stories

[edit]- "Inflexure", Astounding Science Fiction (October 1934)

- "Trouble with Water", Unknown (March 1939)

- "The Old Die Rich", Galaxy Science Fiction (March 1953)

- "Someone to Watch Over Me" (with Floyd Gold), Galaxy Science Fiction (October 1959)

- "Inside Man", Galaxy Science Fiction, October 1965

- "The Transmogrification of Wamba's Revenge", Galaxy, October 1967

- "The Riches of Embarrassment", Galaxy, April 1968

- "The Villains from Vega IV" (with E. J. Gold), Galaxy, October 1968

- "And Three to Get Ready"

- "At the Post"

- "Don't Take It to Heart"

- "Hero"

- "Love in the Dark"

- "Man of Parts"

- "The Man with English"

- "No Charge for Alterations"

- "Problem in Murder"

- "Trouble with Water"

Novels

[edit]- A Matter of Form (1938)

- None But Lucifer (with L. Sprague de Camp) (1939)

Collections

[edit]- The Old Die Rich (1955)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Horace Leonard Gold" Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2022-07-21

- ^ a b Gold, H. L. (June 1951). "Looking Forward". Galaxy Science Fiction. p. 2. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Gold, H. L. (July 1954). "Career Offered". Galaxy. p. 4. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Biography by Joe Desris, in Batman Archives, Volume 3 (DC Comics, 1994), p. 223 ISBN 1563890992

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (August 1965). "Old Home Month". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 4–7.

- ^ Pohl, Frederik (October 1965). "The Day After Tomorrow". Editorial. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 4–7.

- ^ "Recommended Reading," F&SF, August 1955, p. 94.

References

[edit]- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, pp. 505–506.

External links

[edit]- Works by Horace Leonard Gold at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about H. L. Gold at the Internet Archive

- Works by H. L. Gold at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- H. L. Gold at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Audio files

[edit]- 1914 births

- 1996 deaths

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- United States Army personnel of World War II

- 20th-century American novelists

- American fantasy writers

- American male novelists

- American science fiction writers

- American science fiction editors

- Galaxy Science Fiction

- American male short story writers

- Jewish American novelists

- 20th-century American short story writers

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American Jews