Hoosiers (film)

| Hoosiers | |

|---|---|

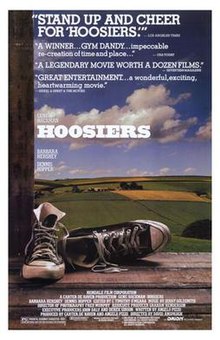

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Anspaugh |

| Written by | Angelo Pizzo |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Fred Murphy |

| Edited by | Carroll Timothy O'Meara |

| Music by | Jerry Goldsmith |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6 million[1] |

| Box office | $28.6 million[2] |

Hoosiers (released in some countries as Best Shot[3]) is a 1986 American sports drama film written by Angelo Pizzo and directed by David Anspaugh in his feature directorial debut. It tells the story of a small-town Indiana high school basketball team that enters the state tournament. It is inspired in part by the Milan High School team who won the 1954 state championship.

Gene Hackman stars as Norman Dale, a new coach with a spotty past. The film co-stars Barbara Hershey and Dennis Hopper, whose role as the basketball-loving town drunk earned him an Oscar nomination. Jerry Goldsmith was also nominated for an Academy Award for his score. In 2001, Hoosiers was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant."[4][5]

Plot

[edit]In 1951, Norman Dale arrives in rural Hickory, Indiana. His old friend, high school principal Cletus Summers, has hired him as the civics and history teacher and as head basketball coach.

The townspeople, passionate about basketball, are disappointed that Hickory's best player, Jimmy Chitwood, has left the team following the death of the previous coach, who had been a surrogate father to Jimmy. At a meet-and-greet, Dale tells the townspeople he used to coach college basketball. The next day, fellow teacher Myra Fleener warns Dale not to recruit Jimmy. She is encouraging Jimmy to focus solely on his studies so that he will have a future away from Hickory.

The small school has only seven players. At the first practice, Dale dismisses Buddy Walker for rudeness, causing another player, Whit Butcher, to walk out in protest. Dale begins drilling the others (Rade Butcher, Merle Webb, Everett Flatch, Strap Purl, and equipment manager Ollie McLellan) with fundamentals and conditioning but no scrimmages or shooting, much to the Huskers' dismay. Whit later apologizes to Dale and rejoins the team.

Dale instructs the Huskers to pass four times before shooting. During the season opener, Rade disobeys and repeatedly makes baskets without passing first. Dale benches him for the rest of the game, even when Merle fouls out, leaving only four Huskers on the floor. In a subsequent game, when a rival player jabs Dale in the chest during an on-court argument, Rade jumps to his defense and hits the player. During the altercation, Principal Summers, acting as assistant coach, suffers a mild heart attack. Dale further erodes community support by employing a slow, defensive style that does not immediately produce results. Dale also loses his temper on court and gets ejected from two games.

With Summers laid up, Dale asks former Husker Wilbur "Shooter" Flatch, Everett's alcoholic father, to be his assistant coach, with the requirement that Shooter be sober during all games and practices. Shooter agrees, on the condition that Dale not get ejected from any more games. Dale's choice of Shooter confounds the town and embarrasses Everett.

Mid-season, disgruntled townspeople decide to vote on dismissing Dale. Before the meeting, Fleener, sensing something amiss regarding Dale's past, uncovers years-old information about his hitting a player and being banned from coaching. However, Fleener chooses not to reveal this fact to the townspeople, instead telling them at the meeting to give Dale another chance. Nevertheless, they vote to fire the coach. Then Jimmy Chitwood arrives and announces he will rejoin the team, but only if Dale remains as coach. A new vote is taken, and the residents overwhelmingly choose to keep Dale.

After Jimmy's return, the reinvigorated Huskers rack up a series of wins. To prove to the townspeople (and to Shooter himself) Shooter's value to the team, Dale intentionally gets ejected from a game. This forces Shooter to devise a play that helps Hickory win on a last-second shot. Shooter also regains the respect of his son, Everett.

Despite a setback when Shooter relapses, the team advances through the state tournament with Jimmy's strong performance. Unsung players, such as short Ollie and devoutly religious Strap, also contribute. Hickory reaches the championship game in Indianapolis. At Butler Fieldhouse, and before the largest crowd they have ever seen, the Huskers face long odds to defeat the heavily favored South Bend Central Bears, who have taller and more athletic players. After falling behind, Hickory fights their way back and ties the game with just a few seconds left. Dale calls a timeout and sets up a play where Jimmy will be a decoy for Merle, who will take the last shot. The Huskers look uncomfortable, and when Dale demands to know what's wrong, Jimmy simply says, "I'll make it." He scores just before the buzzer sounds, securing the victory.

Sometime in the future, a boy shoots baskets in Hickory's home gym. A large black-and-white team portrait is seen hanging on the wall, and a voiceover from Dale states, "I love you guys."

Cast

[edit]- Gene Hackman as Norman Dale

- Barbara Hershey as Myra Fleener

- Dennis Hopper as Shooter Flatch

- Sheb Wooley as Cletus Summers

- Maris Valainis as Jimmy Chitwood

- David Neidorf as Everett Flatch

- Brad Long as Buddy Walker

- Steve Hollar as Rade Butcher

- Brad Boyle as Whit Butcher

- Wade Schenck as Ollie McLellan

- Kent Poole as Merle Webb

- Scott Summers as Strap Purl

- Fern Persons as Opal Fleener

- Chelcie Ross as George Walker

- Robert Swan as Rollin Butcher

- Michael Sassone as Preacher Purl

- Gloria Dorson as Millie

- Michael O'Guinne as Rooster

- Wil Dewitt as Reverend Doty

- John Robert Thompson as Sheriff Finley

- Hilliard Gates as Radio Announcer

Inspiration

[edit]

The film is inspired in part by the story of the 1954 Indiana state champions, Milan High School (/ˈmaɪlən/ MY-lən). The phrase "inspired by a true story" is more appropriate than "based on a true story" because the two teams have little in common.[6]

In most U.S. states, high school athletic teams are divided into different classes, usually based on the number of enrolled students, with separate state championship tournaments held for each classification. In 1954, Indiana conducted a single state basketball tournament for all its high schools. This practice continued until 1997.[6]

Some plot points are similar to Milan's real story. Like the film's fictional Hickory High School, Milan was a very small high school in a rural, southern Indiana town. Both schools had undersized teams. Both Hickory and Milan won the state finals by 2 points: Hickory won 42–40, and Milan won 32–30. The last seconds of the Hoosiers state final are fairly close to the details of Milan's 1954 final; the last basket in the film was made from virtually the same spot on the floor as Bobby Plump's actual game-winner. The movie's final game was filmed in the same gymnasium that hosted the 1954 Indiana state championship game, Butler University's Hinkle Fieldhouse (called Butler Fieldhouse in 1954) in Indianapolis.[6]

Unlike the film's plot, the 1954 Milan Indians came into the season as heavy favorites and finished the '53–'54 regular season at 19–2. In addition, the 1952–1953 team went to the state semifinals, and they were considered a powerhouse going into the championship season despite the school's small enrollment.[6]

Production

[edit]

During filming in the autumn of 1985, on location at Hinkle Fieldhouse, directors were unable to secure enough extras for shooting the final scenes even after casting calls through the Indianapolis media. To help fill the stands, they invited two local high schools to move a game to the Fieldhouse. Broad Ripple and Chatard, the alma mater of Maris Valainis who played the role of Jimmy Chitwood, obliged, and crowd shots were filmed during their actual game. Fans of both schools came out in period costumes to serve as extras and to supplement the hundreds of locals who had answered the call. At halftime and following the game, actors took to the court to shoot footage of the state championship scenes, including the game-winning shot by Hickory.[citation needed]

The film's producers chose New Richmond, Indiana to serve as the fictional town of Hickory and recorded most of the film's location shots in and around the community. Signs on the roads into New Richmond still recall its role in the film. In addition, the old schoolhouse in Nineveh was used for the majority of the classroom scenes and many other scenes throughout the film.[7]

The home court of Hickory is located in Knightstown and is now known as the "Hoosier Gym."

Pizzo and Anspaugh shopped the script for two years before they finally found investment for the project. Despite this seeming approval, the financiers approved a production budget of only $6 million, forcing the crew to hire most of the cast playing the Hickory basketball team and many of the extras from the local community around New Richmond. Gene Hackman also predicted that the film would be a "career killer." Despite the small budget, dire predictions, and little help from distributor Orion Pictures, Hoosiers grossed over $28 million and received two Oscar nominations (Dennis Hopper for Best Supporting Actor and Jerry Goldsmith for Best Original Score).[8]

Shortly after the film's release, five of the actors who portrayed basketball players in the film were suspended by the NCAA from their real-life college basketball teams for three games. The NCAA determined that they had been paid to play basketball, making them ineligible.[9]

Soundtrack

[edit]| Hoosiers (Best Shot) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 1987 |

| Recorded | 1986 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 39:33 |

| Hoosiers (Original MGM Motion Picture Soundtrack) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | 2012 |

| Recorded | 1986 |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 59:48 |

The music to Hoosiers was written by veteran composer Jerry Goldsmith. Goldsmith used a hybrid of orchestral and electronic elements in juxtaposition to the 1950s setting to score the film. He also helped tie the music to the film by using recorded hits of basketballs on a gymnasium floor to serve as additional percussion sounds.[10] Washington Post film critic Paul Attanasio praised the soundtrack, writing, "And it's marvelously (and innovatively) scored (by composer Jerry Goldsmith), who weaves together electronics with symphonic effects to create a sense of the rhythmic energy of basketball within a traditional setting."[11]

The score would go on to garner Goldsmith an Oscar nomination for Best Original Score, though he ultimately lost to Herbie Hancock for Round Midnight. Goldsmith would later work with filmmakers Angelo Pizzo and David Anspaugh again on their successful 1993 sports film Rudy.

Until 2012, the soundtrack was primarily available under the European title Best Shot, with several of the film's cues not included on the album. In 2012, Intrada Records released Goldsmith's complete score, marking the first time the soundtrack has been released on CD in the United States.[12]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]On Rotten Tomatoes the film holds an approval rating of 91% based on 47 reviews, with an average rating of 7.6/10. The website's critics consensus reads: "It may adhere to the sports underdog formula, but Hoosiers has been made with such loving craft, and features such excellent performances, that it's hard to resist."[13] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 76 out of 100, based on 13 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews."[14] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on A+ to F scale.[15]

Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert praised the film, writing: "What makes Hoosiers special is not its story but its details and its characters. Angelo Pizzo, who wrote the original screenplay, knows small-town sports. He knows all about high school politics and how the school board and the parents' groups always think they know more about basketball than the coach does. He knows about gossip, scandal and vengeance. And he knows a lot about human nature. All of his knowledge, however, would be pointless without Hackman's great performance at the center of this movie. Hackman is gifted at combining likability with complexity — two qualities that usually don't go together in the movies. He projects all of the single-mindedness of any good coach, but then he contains other dimensions, and we learn about the scandal in his past that led him to this one-horse town. David Anspaugh's direction is good at suggesting Hackman's complexity without belaboring it."[16] The New York Times' Janet Maslin echoed Ebert's sentiments, writing, "This film's very lack of surprise and sophistication accounts for a lot of its considerable charm."[17]

Washington Post critics Rita Kempley and Paul Attanasio both enjoyed the film, despite its perceived sentimentalism and lack of originality. Kempley wrote, "Even though we've seen it all before, Hoosiers scores big by staying small."[18] Attanasio pointed out some problems with the film: "[It contains] some klutzy glitches in continuity, and a love story (between Hackman and a sterile, one-note Barbara Hershey) that goes nowhere. The action photography flattens the visual excitement of basketball (you can imagine what a Scorsese would do with it);" but he noted the film's "enormous craftsmanship accumulates till you're actually seduced into believing all its Pepperidge Farm buncombe. That's quite an achievement."[11]

Time magazine's Richard Schickel praised the performance of Gene Hackman, writing that he was

wonderful as an inarticulate man tense with the struggle to curb a flaring, mysterious anger.[19]

Variety wrote that the

pic belongs to Hackman, but Dennis Hopper gets another opportunity to put in a showy turn as a local misfit.[20]

Pat Graham of the Chicago Reader was the rare dissenter, writing of the film that

Director David Anspaugh seems only marginally concerned with basketball thematics: what matters most is feeding white-bread fantasies (the film is set in the slow-footed 50s, when blacks are only a rumor and nobody's ever heard of slam 'n' jam) and laying on the inspirational corn.... Bobby Knight would not be amused, though Tark the Shark might've had a good laugh at the naive masquerade.[21]

Accolades

[edit]Hoosiers has been named by many publications as the best or one of the best sports movies ever made.[6][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

Hoosiers was ranked number 13 by the American Film Institute on its 100 Years... 100 Cheers list of most inspirational films.[30] The film was the choice of the readers of USA Today as the best sports movie of all time. In 2001, Hoosiers was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" due in part to an especially large number of nominations from Indiana citizens.[31][4]

In June 2008, AFI revealed its "Ten Top Ten" — the best ten films in ten classic American film genres — after polling over 1,500 people from the creative community. Hoosiers was acknowledged as the fourth best film in the sports genre.[29][32]

A museum to commemorate the real-life achievements of the 1954 Milan team has been established.[33]

In 2015, MGM partnered with the Indiana Pacers to create Hickory uniforms inspired by the film. The Pacers first wore the tribute uniforms during select games in the 2015–16 NBA regular season in honor of the film's 30th anniversary.[34]

In April 2017, Vice President (and former governor of Indiana) Mike Pence said that Hoosiers is the "greatest sports movie ever made" while traveling on a flight from Indonesia to Australia with a pool of journalists.[35]

American Film Institute Lists

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Review: "Touchback" is an inspiring drama that will make you smile. Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine WOOD-TV. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ^ "Hoosiers". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Hoosiers (1986) - Release Info - IMDb". IMDb. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ a b "Librarian of Congress Names 25 More Films to National Film Registry" (Press release). Library of Congress. December 18, 2001. Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Merron, Jeff. "'Hoosiers' in reel life". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ "Sites | The Hoosiers Archive". hoosiersarchive.com. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ "ESPN the Magazine Movie Spectacular - An oral history of "Hoosiers," an iconic sports movie - ESPN". November 16, 2010. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

- ^ "5 Players Banned After Movie Role". The New York Times. November 28, 1986. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Hoosiers Archived January 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine soundtrack review at Filmtracks.com Archived January 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Attanasio, Paul. "Hoosiers," Archived December 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post (Feb. 27, 1987).

- ^ Hoosiers Archived January 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine soundtrack listing at Intrada.com Archived March 23, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Hoosiers (1986)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ "Hoosiers". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 21, 2018. Retrieved February 6, 2020.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Hoosiers," Archived April 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Sun-Times (February 27, 1987).

- ^ Maslin, Janet. "Film: Gene Hackman as a Coach in 'Hoosiers,'" New York Times (Feb. 27, 1987).

- ^ Kempley, Rita. "Hoosiers," Archived December 10, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Washington Post (Feb. 27, 1987).

- ^ Schickel, Richard. "Cinema: Knight-Errant Hoosiers," Archived March 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Time (Feb. 9, 1987).

- ^ Variety Staff. "Hoosiers," Variety (Dec. 31, 1985).

- ^ Graham, Pat. "Hoosiers," Archived February 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Chicago Reader. Accessed Mar. 27, 2012.

- ^ "Best Sports Movies of All Time". Moviefone. March 23, 2007. Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "The 25 Greatest Sports Movies Ever". NY Daily News. New York. May 29, 2009. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Page 2's Top 20 Sports Movies of All-Time". ESPN.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "The 50 Greatest Sports Movies Of All Time!". Sports Illustrated. August 4, 2003. Archived from the original on July 29, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Greatest Sports Films". FilmSite.org. Archived from the original on July 22, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Top Sports Movies - Hoosiers - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ Shulman, Calvin; Kidd, Patrick (February 13, 2008). "The 50 greatest sporting movies". The Times. London. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ a b American Film Institute (June 17, 2008). "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres". ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ O'Dell, Cary. ""GET THE PICTURE!": Public Nominations to the National Film Registry | Features | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com/. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ "Top 10 Sports". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ^ "Milan '54 Museum". Milan '54 Museum, Inc. 2005. Archived from the original on March 24, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2010.

- ^ "Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Pacers Bring "Hoosiers" Inspired Uniform to NBA". Pacers.com (Press release). NBA Media Ventures, LLC. July 21, 2015. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- ^ Gartland, Dan. "Mike Pence thinks 'Hoosiers' is 'greatest sports movie ever'". SI.com. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Hoosiers at IMDb

- Hoosiers at Rotten Tomatoes

- Hoosiers at the TCM Movie Database

- The Hoosiers Archive

- Hoosiers at Box Office Mojo

- Hoosiers at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Hoosiers essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 791-792 [1]

- 1986 films

- 1980s sports drama films

- 1980s high school films

- 1986 independent films

- American sports drama films

- American basketball films

- American independent films

- American teen films

- Basketball in Indiana

- Films directed by David Anspaugh

- Films scored by Jerry Goldsmith

- Films set in 1951

- Films set in 1952

- Films set in Indiana

- Films shot in Indiana

- Orion Pictures films

- Sports films based on actual events

- United States National Film Registry films

- Biographical films about educators

- Biographical films about sportspeople

- Cultural depictions of basketball players

- Cultural depictions of American people

- 1986 directorial debut films

- 1986 drama films

- Indiana culture

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s American films

- Films about high school sports

- English-language sports drama films

- English-language independent films