Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2020) |

| Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | X-linked mental retardation-hypotonic facies syndrome 1 (MRXHF1), Carpenter–Waziri syndrome, Chudley–Lowry syndrome, SFMS, Holmes–Gang syndrome and Juberg–Marsidi syndrome (JMS),[1][2] |

| |

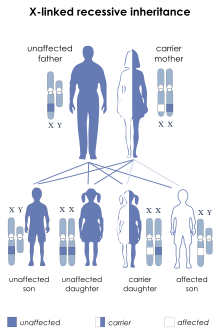

| Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome has an X-linked recessive pattern of inheritance. | |

Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome (SFMS1) is a congenital disorder that causes birth defects. This syndrome was named after Richard D. Smith, Robert M. Fineman and Gart G. Myers who discovered it around 1980.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

SFMS affects the skeletal and nervous system. This syndrome's external signs would be an unusual facial appearance with their heads being slightly smaller than average, a narrow face (clinically known as dolichocephaly), a large mouth with a drooping lower lip that is held open, protruding upper jaw, widely spaced upper front teeth, an underdeveloped chin, cleft palate and exotropied-slanted eyes with drooping eyelids.

Males who have SFMS have short stature and a thin body build. The skin is lightly pigmented with multiple freckles. They may have scoliosis and chest abnormalities.

Affected boys have reduced muscle tone as infants-young children. X-rays sometimes show that their bones are underdeveloped and show characteristics of the bones of younger children. Boys under the age of 10 usually have reduced muscle tone but later, patients with SFMS over the age of 10 have increased muscle tone and reflexes that cause spasticity. Their hands are short with unusual palm creases with short, shaped fingers and foot abnormalities, such as are shortened and fused toes.

They have spleen agenesis (absence of the spleen) and the genitals may also show undescended testes ranging from mild to severe that leads to female gender assignment.

People who have SFMS have severe intellectual disability (formerly known as mental retardation). They are restless on occasion, have behavioral problems, seizures and severe delay in language development. They are self-absorbed with reduced ability to socialize with others around them. They also have psychomotor retardation which is the slowing-down of thoughts and a reduction of physical movements. They have cortical atrophy (also known as degeneration) of the brain's outer layer, although it is usually found in older affected people.[4]

Genetics

[edit]SFMS is an X-linked disease by chromosome Xq13. X-linked diseases map to the human X chromosome because this syndrome is an X chromosome linked females who have two chromosomes are not affected but because males only have one X chromosome, they are more likely to be affected and show the full clinical symptoms. This disease only requires one copy of the abnormal X-linked gene to display the syndrome. Since females have two X chromosomes, the effect of one X chromosome is recessive and the second chromosome masks the affected chromosome.[5]

Affected fathers can never pass this X-linked disease to their sons but affected fathers can pass the X-linked gene to their daughters who has a 50% chance to pass this disease-causing gene to each of her children. Since females who inherit this gene do not show symptoms, they are called carriers. Each of the female's carrier's son has a 50% chance to display the symptoms but none of the female carrier's daughters would display any symptoms.[4]

Some patients with SFMS have been founded to have a mutation of the gene in the ATRX on the X chromosome, also known as the Xq13 location. ATRX is a gene disease that is associated with other forms of X-linked mental retardation like Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome, Carpenter syndrome, Juberg-Marsidi syndrome, and spastic paraplegia. It is possible that patients with SFMS have Alpha-thalassemia/mental retardation syndrome without the affected hemoglobin H that leads to Alphathalassemia/ mental retardation syndrome in the traditionally recognized disease.[5]

Diagnosis

[edit]The assessment for Smith-Finemen-Myers syndrome like any other mental retardation includes a detailed family history and physical exam that tests the mentality of the patient. The patient also gets a brain and skeletal imaging though CT scans or x-rays. They also does a chromosome study and certain other genetic biochemical tests to help figure out any other causes for the mental retardation.

The diagnosis of SFMS is based on visible and measurable symptoms. Until 2000, SFMS was not known to be associated with any particular gene. As of 2001, scientists do not yet know if other genes are involved in this rare disease. Generic analysis of the ATRX gene may prove to be helpful in diagnosis of SFMS.[6]

Treatments

[edit]Treatments are usually based on the individuals symptoms that are displayed. The seizures are controlled with anticonvulsant medication. For the behavior problems, the doctors prescribe a few medications and behavioral modification routines that involve therapists and other types of therapy. Even if mental retardation is severe, it does not seem to shorten the lifespan of the patient or to get worse with age.

History

[edit]On September 15, 1991 in Sydney, Australia, the Prince of Wales Children's Hospital, reported on two brothers with a distinct facial appearance, severe mental retardation, short stature, cryptorchidism (undescended testicle), asplenia in one (absent spleen), dramatic failure to thrive, early hypotonia, and later hypertonia, all suggestive of the Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome. All five of the reported cases have been males, suggesting X-linked inheritance.[7]

On September 23, 1998 at the Hospital Injury Research and Rehabilitation at the University of São Paulo in Bauru, Brazil report on two boys, monozygotic twins born to normal and non consanguineous parents, presenting with an unusual facial appearance, cortical atrophy, dolichocephaly, short stature, cleft palate, micrognathia, prominent upper central incisors, bilateral Sidney line, minor foot deformities, unstableness in walking, early hypotonia, hyperreflexia, hyperactivity, psychomotor retardation, and severe delay in language development. These symptoms resemble those previously described in the Smith–Fineman–Myers syndrome.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 309580

- ^ Saugier-Veber P, Abadie V, Moncla A, et al. (June 1993). "The Juberg-Marsidi syndrome maps to the proximal long arm of the X chromosome (Xq12-q21)". American Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (6): 1040–5. PMC 1682258. PMID 8503439.

- ^ "Smith-Fineman-Myers syndrome (Richard D. Smith)".

- ^ a b "Health".

- ^ a b Smith-Fineman-Myers Syndrome Summary.

- ^ "Health Content A-Z".

- ^ Adès LC, Kerr B, Turner G, Wise G (September 1991). "Smith-Fineman-Myers syndrome in two brothers". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 40 (4): 467–70. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320400419. PMID 1684092.

- ^ Guion-Almeida ML, Tabith A, Kokitsu-Nakata NM, Zechi RM (September 1998). "Smith-Fineman-Myers syndrome in apparently monozygotic twins". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 79 (3): 205–8. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980923)79:3<205::AID-AJMG11>3.0.CO;2-L. PMID 9788563.