Hole

A hole is an opening in or through a particular medium, usually a solid body. Holes occur through natural and artificial processes, and may be useful for various purposes, or may represent a problem needing to be addressed in many fields of engineering. Depending on the material and the placement, a hole may be an indentation in a surface (such as a hole in the ground), or may pass completely through that surface (such as a hole created by a hole puncher in a piece of paper).

Types

[edit]

Holes can occur for a number of reasons, including natural processes and intentional actions by humans or animals. Holes in the ground that are made intentionally, such as holes made while searching for food, for replanting trees, or postholes made for securing an object, are usually made through the process of digging. Unintentional holes in an object are often a sign of damage. Potholes and sinkholes can damage human settlements.[1]

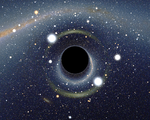

Holes can occur in a wide variety of materials, and at a wide range of scales. The smallest holes observable by humans include pinholes and perforations, but the smallest phenomenon described as a hole is an electron hole, which is a position in an atom or atomic lattice where an electron is missing. The largest phenomenon described as a hole is a supermassive black hole, an astronomical object which can be billions of times more massive than Earth's sun.

The deepest hole on Earth is the man-made Kola Superdeep Borehole, with a true vertical drill-depth of more than 7.5 miles (12 kilometers), which is only a fraction of the nearly 4,000 mile (6,400 kilometer) distance to the center of the Earth.[2]

In mathematics

[edit]

In mathematics, holes are examined in a number of ways. One of these is in homology, which is a general way of associating certain algebraic objects to other mathematical objects such as topological spaces. Homology groups were originally defined in algebraic topology, and homology was originally a rigorous mathematical method for defining and categorizing holes in a mathematical object called a manifold. The initial motivation for defining homology groups was the observation that two shapes can be distinguished by examining their holes.[3] For instance, a circle is not a disk because the circle has a hole through it while the disk is solid,[4] and the ordinary sphere is not a circle because the sphere encloses a two-dimensional hole while the circle encloses a one-dimensional hole. Because a hole is immaterial, it is not immediately obvious how to define one or distinguish it from others.

Another is the notion of homotopy group: these are invariants of a topological space that, when non-trivial (one also says in this case that the space is not k-connected), detect the presence of "holes" in the sense that the space contains a sphere that cannot be contracted to a point. The term of hole is often used informally when discussing these objects.[5]

For surfaces a notion closer to the intuitive meaning exists: the genus of a connected, orientable surface is an integer representing the maximum number of cuttings along non-intersecting closed simple curves without rendering the resultant manifold disconnected.[6] In layman's terms, it is exactly the number of "holes" the surface has, when represented as a submanifold in 3-space.

In physics

[edit]In physics, antimatter is pervasively described as a hole, a location that, when brought together with ordinary matter to fill the hole, results in both the hole and the matter cancelling each-other out. This is analogous to patching a pothole with asphalt, or filling a bubble below the surface of water with an equal amount of water to cancel it out. The most direct example is the electron hole; a fairly general theoretical description is provided by the Dirac sea, which treats positrons (or anti-particles in general) as holes. Holes provide one of the two primary forms of conduction in a semi-conductor, that is, the material from which transistors are made; without holes, current could not flow, and transistors turn on and off by enabling or disabling the creation of holes.

In biology

[edit]

Animal bodies tend to contain specialized holes which serve various biological functions, such as the intake of oxygen or food, the excretion of waste, and the intake or expulsion of other fluids for reproductive purposes. In some simple animals, a single hole serves all of these purposes.[7] The formation of holes is a significant event in the development of an animal:

All animals start out in development with one hole, the blastopore. If there are two holes, the second hole forms later. The blastopore can arise at the top or the bottom of the embryo.[7]

Gramicidin A, a polypeptide with a helical shape, has been described as a portable hole. When it forms a dimer, it can embed itself in cellular bilayer membranes and form a hole through which water molecules can pass.[8]

Blind and through

[edit]

In engineering, machining, and tooling, a hole may be a blind hole or a through hole (also called a thru-hole or clearance hole). A blind hole is a hole that is reamed, drilled, or milled to a specified depth without breaking through to the other side of the workpiece. A through hole is a hole that is made to go completely through the material of an object. In other words, a through hole is a hole that goes all the way through something. Taps used for through holes are generally tapered since it will tap faster and the chips will be released when the tap exits the hole.

The etymology of the blind hole is that it is not possible to see through it. It may also refer to any feature that is taken to a specific depth, more specifically referring to internally threaded hole (tapped holes). Not considering the drill point, the depth of the blind hole, conventionally, may be slightly deeper than that of the threaded depth.

There are three accepted methods of threading blind holes:

- Conventional tapping, especially with bottom taps

- Single-point threading, where the workpiece is rotated, and a pointed cutting tool is fed into the workpiece at the same rate as the pitch of the internal thread. Single-pointing inside a blind hole, like boring inside one, is inherently more challenging than doing so in a through hole. This was especially true in the era when manual machining was the only method of control. Today, CNC makes these tasks less stressful, but nevertheless still more challenging than with through holes.

- Helical interpolation, where the workpiece remains stationary and Computer Numerical Control (CNC) moves a milling cutter in the correct helical path for a given thread, milling the thread.

At least two U.S. tool manufacturers have manufactured tools for thread milling in blind holes: Ingersoll Cutting Tools of Rockford, Illinois, and Tooling Systems of Houston, Texas, who introduced the Thread Mill in 1977, a device that milled large internal threads in the blind holes of oil well blowout preventers. Today many CNC milling machines can run such a thread milling cycle (see a video of such a cut in the "External links" section).

One use of through holes in electronics is with through-hole technology, a mounting scheme involving the use of leads on the components that are inserted into holes drilled in printed circuit boards (PCB) and soldered to pads on the opposite side either by manual assembly (hand placement) or by the use of automated insertion mount machines.[9][10]

Pinholes

[edit]A pinhole is a small hole, usually made by pressing a thin, pointed object such as a pin through an easily penetrated material such as a fabric or a very thin layer of metal. Similar holes made by other means are also often called pinholes. Pinholes may be intentionally made for various reasons. For example, in optics pinholes are used as apertures to select certain rays of light. This is used in pinhole cameras to form an image without the use of a lens.[11] Pinholes on produce packaging have been used to control the atmosphere and relative humidity within the packaging.[12]

In many fields, pinholes are a harmful side effect of manufacturing processes. For example, in the assembly of microcircuits, pinholes in the dielectric insulator layer coating the circuit can cause the circuit to fail. Therefore, "[t]o avoid pinholes that might protrude through the entire thickness of the dielectric layer, it is a common practice to screen several layers of dielectric with drying and firing after each screening", thereby preventing the pinholes from becoming continuous.[13]

Philosophy and psychology

[edit]It has been noted that holes occupy an unusual ontological position in philosophy, as people tend to refer to them as tangible and countable objects, when in fact they are the absence of something in another object.[14][15]

In the study of visual perception, a hole is a special case of figure-ground, because the ground region is entirely surrounded by the figure. For a region to be perceived as a visual hole three factors are important: depth factors indicating that the enclosed region lies behind; grouping between the enclosed region and the surround; and figural factors (for example symmetry, convexity, or familiarity) that lead to the perception of a figure rather than a hole.[16][17]

There is a debate on whether holes are special and whether they are perceived as having their own shape. They may be special in some cases, but not in the ownership of the contours.[18]

Some people have an aversion to the sight of irregular patterns or clusters of small holes, a condition called trypophobia.[19][20] Researchers hypothesize that this is the result of a biological revulsion that associates trypophobic shapes with danger or disease, and may therefore have an evolutionary basis.[21][19]

In culture and as a metaphor

[edit]

An example of the use of holes in popular culture can be found in the Beatles lyric from the song, "A Day in the Life", from their 1967 album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band:

I read the news today, oh boy:

Four thousand holes in Blackburn Lancashire.

And though the holes were rather small,

They had to count them all,

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall.[22]

The reference to 4,000 holes was written by John Lennon, and inspired by a Far & Near news brief from the same 17 January edition of the Daily Mail, which had also provided inspiration for previous verses of the song. Under the headline "The holes in our roads", the brief stated: "There are 4,000 holes in the road in Blackburn, Lancashire, or one twenty-sixth of a hole per person, according to a council survey. If Blackburn is typical, there are two million holes in Britain's roads and 300,000 in London".[23] Holes have also been described as ontological parasites because they can only exist as aspects of another object.[14] The psychological concept of a hole as a physical object is taken to its logical extreme in the fictional concept of a portable hole, exemplified in role-playing games and characterized as a "hole" that a person can carry with them, keep things in, and enter themselves as needed.[24]

In art holes are sometimes referred to as negative space, as in the case of the Japanese concept of Ma.

Holes can also be referenced metaphorically as existing in non-tangible things. For example, a person who provides an account of an event that lacks important details can be said to have "holes in their story", and a fictional work with unexplained narrative elements can be said to have plot holes.[25] A person who has suffered loss is often referred to as having a "hole in their heart". The concept of a "God-shaped hole" occurs in religious discourse:

[H]umans are commonly said to have “a God-shaped hole” in our souls. If you are a religious person, you can explain the hole by saying that God put it there in order to make it easier for us to receive Him. If you are a naturalist or an atheist, you believe the God-shaped hole is in our minds, not our souls. You then look for reasons that the concept of God might have evolved in our species.[26]

Unicode

[edit]| Hole Emoji |

|---|

|

| Unicode symbol for HOLE, U+1F573 ( 🕳 ) |

The Unicode symbol for HOLE, U+1F573, was approved in 2014 as part of the Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs chart in Unicode 7.0,[27] and was part of Emoji 1.0, published in 2015.[28] As pictorial representations for emoji are platform-dependent, Emojipedia shows images of the hole symbol as depicted on various platforms.[29]

Gallery

[edit]-

Hole in the ground dug by a fox as its burrow.

-

Hole in a Eucalyptus tree used as a nest by Lorikeets.

-

Trees visible through a large hole in a tree trunk in Laos.

-

Hole in a cloud over Karawanks, Slovenia.

-

Sock with a hole in it, through which the foot is visible.

-

Simulated view of a black hole in front of the Large Magellanic Cloud.

-

First image of a black hole by the Event Horizon Telescope.

-

Close-up view of a printed circuit board showing component lead holes (gold-plated) with through-hole plating (Through-hole technology).

-

Sound holes precisely carved into the surface of a guitar can facilitate a desired sound.

-

First World War cartoon Well, if you knows of a better 'ole, go to it by Bruce Bairnsfather, 1915.

-

A hole in the Berlin Wall, 2019.

-

A handheld hole punch, used to make holes in paper and similar materials.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The hole story". The Economist. 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- ^ "What's At The Bottom Of The Deepest Hole On Earth?". 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-08-17.

- ^ Richeson, D.; Euler's Gem: The Polyhedron Formula and the Birth of Topology, Princeton University (2008), p. 254.

- ^ Arnold, Bradford Henry (2013). Intuitive Concepts in Elementary Topology. Dover Books on Mathematics. Courier / Dover Publications. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-48627576-5.

- ^ Matoušek, Jiří (2007). Using the Borsuk-Ulam Theorem: Lectures on Topological Methods in Combinatorics and Geometry (2nd ed.). Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-00362-5.

Written in cooperation with Anders Björner and Günter M. Ziegler

, Section 4.3. - ^ Munkres, James R. Topology. Vol. 2. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2000.

- ^ a b Dunn, Casey (2009-11-06). "A tale of two holes – Creature Cast – Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com.

- ^ Mouritsen, Ole G. (2005). Life - As a Matter of Fat: The Emerging Science of Lipidomics. Springer. p. 186. ISBN 978-3-54023248-3. OCLC 1156049123.

- ^ Electronic Packaging: Solder Mounting Technologies in K. H. Buschow et al (eds.), Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, Elsevier, 2001 ISBN 0-08-043152-6, pp. 2708–2709.

- ^ Horowitz, Paul; Hill, Winfield (1989). The art of electronics (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52137095-0.

- ^ What is a Pinhole Camera?, pinhole.cz.

- ^ Enrique Ortega-Rivas, Processing Effects on Safety and Quality of Foods (2010), p. 280.

- ^ James J. Licari, Leonard R. Enlow, Hybrid Microcircuit Technology Handbook, 2nd Edition (2008), p. 162.

- ^ a b Casati, Roberto; Varzi, Achille (2018-12-18). "Holes". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Lewis, DK, Lewis, SR (1970). "Holes: With Stephanie Lewis". Philosophical Papers Volume I. Australasian Journal of Philosophy. 48: 206–212. doi:10.1093/0195032047.003.0001. ISBN 0195032047.

- ^ Rock, Irv (1973). Orientation and Form. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0125912501.

- ^ Abrahams, Marc (2005). "A hole full of surprises".

- ^ Bertamini M (2006). "Who owns the contour of a visual hole?". Perception. 35 (7): 883–894. doi:10.1068/p5496. PMID 16970198. S2CID 8073234.

- ^ a b Martínez-Aguayo, Juan Carlos; Lanfranco, Renzo C.; Arancibia, Marcelo; Sepúlveda, Elisa; Madrid, Eva (2018). "Trypophobia: What Do We Know So Far? A Case Report and Comprehensive Review of the Literature". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 9: 15. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00015. ISSN 1664-0640. PMC 5811467. PMID 29479321.

This article incorporates text by Juan Carlos Martínez-Aguay, Renzo C. Lanfranco, Marcelo Arancibia, Elisa Sepúlveda and Eva Madrid available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Juan Carlos Martínez-Aguay, Renzo C. Lanfranco, Marcelo Arancibia, Elisa Sepúlveda and Eva Madrid available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Le, An T. D.; Cole, Geoff G.; Wilkins, Arnold J. (2015-01-30). "Assessment of trypophobia and an analysis of its visual precipitation". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 68 (11): 2304–2322. doi:10.1080/17470218.2015.1013970. PMID 25635930. S2CID 42086559.

- ^ Milosevic, Irena; McCabe, Randi E. (2015). Phobias: The Psychology of Irrational Fear. ABC-CLIO. pp. 401–402. ISBN 978-1-61069576-3. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ^ "Photographic impressions of Beatle songs by Art Kane", LIFE, Vol. 65, No. 12 (1968-09-20), p. 67.

- ^ "Far & Near: The holes in our roads". The Daily Mail. No. 21994. 1967-01-17. p. 7.

- ^ David Zeb Cook, Jean Rabe, Warren Spector, Dungeon Master Guide for the AD&D Game (1995), p. 235.

- ^ "plot hole | Definition of plot hole in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 2017-09-07. Retrieved 2017-09-07.

- ^ Blakey Vermeule, Why Do We Care about Literary Characters? (2010), p. 10.

- ^ "Unicode: Miscellaneous Symbols and Pictographs". Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ "Emoji Version 1.0". Retrieved 2018-08-20.

- ^ "Emojipedia: Hole". Retrieved 2018-08-20.