History of video games

| Part of a series on the |

| History of video games |

|---|

The history of video games began in the 1950s and 1960s as computer scientists began designing simple games and simulations on minicomputers and mainframes. Spacewar! was developed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) student hobbyists in 1962 as one of the first such games on a video display. The first consumer video game hardware was released in the early 1970s. The first home video game console was the Magnavox Odyssey, and the first arcade video games were Computer Space and Pong. After its home console conversions, numerous companies sprang up to capture Pong's success in both the arcade and the home by cloning the game, causing a series of boom and bust cycles due to oversaturation and lack of innovation.

By the mid-1970s, low-cost programmable microprocessors replaced the discrete transistor–transistor logic circuitry of early hardware, and the first ROM cartridge-based home consoles arrived, including the Atari Video Computer System (VCS). Coupled with rapid growth in the golden age of arcade video games, including Space Invaders and Pac-Man, the home console market also flourished. The 1983 video game crash in the United States was characterized by a flood of too many games, often of poor or cloned qualities, and the sector saw competition from inexpensive personal computers and new types of games being developed for them. The crash prompted Japan's video game industry to take leadership of the market, which had only suffered minor impacts from the crash. Nintendo released its Nintendo Entertainment System in the United States in 1985, helping to rebound the failing video games sector. The latter part of the 1980s and early 1990s included video games driven by improvements and standardization in personal computers and the console war competition between Nintendo and Sega as they fought for market share in the United States. The first major handheld video game consoles appeared in the 1990s, led by Nintendo's Game Boy platform.

In the early 1990s, advancements in microprocessor technology gave rise to real-time 3D polygonal graphic rendering in game consoles, as well as in PCs by way of graphics cards. Optical media via CD-ROMs began to be incorporated into personal computers and consoles, including Sony's fledgling PlayStation console line, pushing Sega out of the console hardware market while diminishing Nintendo's role. By the late 1990s, the Internet also gained widespread consumer use, and video games began incorporating online elements. Microsoft entered the console hardware market in the early 2000s with its Xbox line, fearing that Sony's PlayStation positioned as a game console and entertainment device, would displace personal computers. While Sony and Microsoft continued to develop hardware for comparable top-end console features, Nintendo opted to focus on innovative gameplay. Nintendo developed the Wii with motion-sensing controls, which helped to draw in non-traditional players and helped to resecure Nintendo's position in the industry; Nintendo followed this same model in the release of the Nintendo Switch.

From the 2000s and into the 2010s, the industry has seen a shift of demographics as mobile gaming on smartphones and tablets displaced handheld consoles, and casual gaming became an increasingly larger sector of the market, as well as a growth in the number of players from China and other areas not traditionally tied to the industry. To take advantage of these shifts, traditional revenue models were supplanted with ongoing revenue stream models such as free-to-play, freemium, and subscription-based games. As triple-A video game production became more costly and risk-averse, opportunities for more experimental and innovative independent game development grew over the 2000s and 2010s, aided by the popularity of mobile and casual gaming and the ease of digital distribution. Hardware and software technology continues to drive improvement in video games, with support for high-definition video at high framerates and for virtual and augmented reality-based games.

Early history (1948–1970)

As early as 1950, computer scientists were using electronic machines to construct relatively simple game systems, such as Bertie the Brain in 1950 to play tic tac toe, or Nimrod in 1951 for playing Nim. These systems used either electronic light displays and mainly as demonstration systems at large exhibitions to showcase the power of computers at the time.[1][2] Another early demonstration was Tennis for Two, a game created by William Higinbotham at Brookhaven National Laboratory in 1958 for three-day exhibition, using an analog computer and an oscilloscope for a display.[3]

Spacewar! is considered one of the first recognized video games that enjoyed wider distribution behind a single exhibition system. Developed in 1961 for the PDP-1 mainframe computer at MIT, it allowed two players to simulate a space combat fight on the PDP-1's relatively simplistic monitor. The game's source code was shared with other institutions with a PDP-1 across the country as the MIT students themselves moved about, allowing the game to gain popularity.[4]

1970s

Mainframe computer games

In the 1960s, a number of computer games were created for mainframe and minicomputer systems, but these failed to achieve wide distribution due to the continuing scarcity of computer resources, a lack of sufficiently trained programmers interested in crafting entertainment products, and the difficulty in transferring programs between computers in different geographic areas. By the end of the 1970s, however, the situation had changed drastically. The BASIC and C high-level programming languages were widely adopted during the decade, which were more accessible than earlier more technical languages such as FORTRAN and COBOL, opening up computer game creation to a larger base of users. With the advent of time-sharing, which allowed the resources of a single mainframe to be parceled out among multiple users connected to the machine by terminals, computer access was no longer limited to a handful of individuals at an institution, creating more opportunities for students to create their own games. Furthermore, the widespread adoption of the PDP-10, released by Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) in 1966, and the portable UNIX operating system, developed at Bell Labs in 1971 and released generally in 1973, created common programming environments across the country that reduced the difficulty of sharing programs between institutions. Finally, the founding of the first magazines dedicated to computing like Creative Computing (1974), the publication of the earliest program compilation books like 101 BASIC Computer Games (1973), and the spread of wide-area networks such as the ARPANET allowed programs to be shared more easily across great distances. As a result, many of the mainframe games created by college students in the 1970s influenced subsequent developments in the video game industry in ways that, Spacewar! aside, the games of the 1960s did not.

In the arcade and on home consoles, fast-paced action and real-time gameplay were the norm in genres like racing and target shooting. On the mainframe, however, such games were generally not possible due both to the lack of adequate displays (many computer terminals continued to rely on teletypes rather than monitors well into the 1970s and even most CRT terminals could only render character-based graphics) and insufficient processing power and memory to update game elements in real time. While 1970s mainframes were more powerful than arcade and console hardware of the period, the need to parcel out computing resources to dozens of simultaneous users via time-sharing significantly hampered their abilities. Thus, programmers of mainframe games focused on strategy and puzzle-solving mechanics over pure action. Notable games of the period include the tactical combat game Star Trek (1971) by Mike Mayfield, the hide-and-seek game Hunt the Wumpus (1972) by Gregory Yob, and the strategic war game Empire (1977) by Walter Bright. Perhaps the most significant game of the period was Colossal Cave Adventure (or simply Adventure), created in 1976 by Will Crowther by combining his passion for caving with concepts from the newly released tabletop role-playing game (RPG) Dungeons & Dragons (D&D). Expanded by Don Woods in 1977 with an emphasis on the high fantasy of J.R.R. Tolkien, Adventure established a new genre based around exploration and inventory-based puzzle solving that made the transition to personal computers in the late 1970s.

While most games were created on hardware of limited graphic ability, one computer able to host more impressive games was the PLATO system developed at the University of Illinois. Intended as an educational computer, the system connected hundreds of users all over the United States via remote terminals that featured high-quality plasma displays and allowed users to interact with each other in real time. This allowed the system to host an impressive array of graphical and/or multiplayer games, including some of the earliest known computer RPGs, which were primarily derived, like Adventure, from D&D, but unlike that game placed a greater emphasis on combat and character progression than puzzle solving. Starting with top-down dungeon crawls like The Dungeon (1975) and The Game of Dungeons (1975), more commonly referred to today by their filenames, pedit5 and dnd, PLATO RPGs soon transitioned to a first-person perspective with games like Moria (1975), Oubliette (1977), and Avatar (1979), which often allowed multiple players to join forces to battle monsters and complete quests together. Like Adventure, these games ultimately inspired some of the earliest personal computer games.

The first arcade video games and home consoles

The modern video game industry grew out of the concurrent development of the first arcade video game and the first home video game console in the early 1970s in the United States.

The arcade video game industry grew out of the pre-existing arcade game industry, which was previously dominated by electro-mechanical games (EM games). Following the arrival of Sega's EM game Periscope (1966), the arcade industry was experiencing a "technological renaissance" driven by "audio-visual" EM novelty games, establishing the arcades as a healthy environment for the introduction of commercial video games in the early 1970s.[5] In the late 1960s, a college student Nolan Bushnell had a part-time job at an arcade where he became familiar with EM games, watching customers play and helping to maintain the machinery while learning how it worked and developing his understanding of how the game business operates.[6]

In 1966, while working at Sanders Associates, Ralph Baer came up with an idea for an entertainment device that could be hooked up to a television monitor. Presenting this to his superiors at Sanders and getting their approval, he, along with William Harrison and William Rusch, refined Baer's concept into the "Brown Box" prototype of a home video game console that could play a simple table tennis game. The three patented the technology, and Sanders, not in the commercialization business, sold licenses to the patents to Magnavox to commercialize. With Baer's help, Magnavox developed the Magnavox Odyssey, the first commercial home console, in 1972.

Concurrently, Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney had the idea of making a coin-operated system to run Spacewar! By 1971, the two had developed Computer Space with Nutting Associates, the first arcade video game.[7] Bushnell and Dabney struck out on their own and formed Atari. Bushnell, inspired by the table tennis game on the Odyssey, hired Allan Alcorn to develop an arcade version of the game, this time using discrete transistor–transistor logic (TTL) electronic circuitry. Atari's Pong was released in late 1972 and is considered the first successful arcade video game. It ignited the growth of the arcade game industry in the United States from both established coin-operated game manufacturers like Williams, Chicago Coin, and the Midway subsidiary of Bally Manufacturing, and new startups such as Ramtek and Allied Leisure. Many of these were Pong clones using ball-and-paddle controls, and led to saturation of the market in 1974, forcing arcade game makers to try to innovate new games in 1975. Many of the newer companies created in the wake of Pong failed to innovate on their own and shut down, and by the end of 1975, the arcade market had fallen by about 50% based on new game sale revenues.[8] Further, Magnavox took Atari and several other of these arcade game makers to court over violations of Baer's patents. Bushnell settled the suit for Atari, gaining perpetual rights for the patents for Atari as part of the settlement.[9] Others failed to settle, and Magnavox won around $100 million in damages from these patent infringement suits before the patents expired in 1990.[10]

Arcade video games caught on quickly in Japan due to partnerships between American and Japanese corporations that kept the Japan companies abreast of technology developments within the United States. The Nakamura Amusement Machine Manufacturing Company (Namco) partnered with Atari to import Pong into Japan in late 1973. Within the year, Taito and Sega released Pong clones in Japan by mid-1973. Japanese companies began developing novel games and exporting or licensing them through partners in 1974.[11] Among these included Taito's Gun Fight (originally Western Gun in its Japanese release), which was licensed to Midway. Midway's version, released in 1975, was the first arcade video game to use a microprocessor rather than discrete TTL components.[12] This innovation drastically reduced the complexity and time to design of arcade games and the number of physical components required to achieve more advanced gameplay.[13]

The dedicated console market

The Magnavox Odyssey never caught on with the public, due largely to the limited functionality of its primitive discrete electronic component technology.[8] By mid-1975, large-scale integration (LSI) microchips had become inexpensive enough to be incorporated into a consumer product.[8] In 1975, Magnavox reduced the part count of the Odyssey using a three-chip set created by Texas Instruments and released two new systems that only played ball-and-paddle games, the Magnavox Odyssey 100 and Magnavox Odyssey 200. Atari, meanwhile, entered the consumer market that same year with the single-chip Home Pong system. The next year, General Instrument released a "Pong-on-a-chip" LSI and made it available at a low price to any interested company. Toy company Coleco Industries used this chip to create the million-selling Telstar console model series (1976–77).

These initial home video game consoles were popular, leading to a large influx of companies releasing Pong and other video game clones to satisfy consumer demand. While there were only seven companies that were releasing home consoles in 1975, there were at least 82 by 1977, with more than 160 different models that year alone that were easily documented. A large number of these consoles were created in East Asia, and it is estimated that over 500 Pong-type home console models were made during this period.[8] As with the prior paddle-and-ball saturation in the arcade game field by 1975 due to consumer weariness, dedicated console sales dropped sharply in 1978, disrupted by the introduction of programmable systems and Handheld electronic games.[8]

Just as dedicated consoles were waning in popularity in the West, they briefly surged in popularity in Japan. These TV geemu were often based on licensed designs from the American companies, manufactured by television manufacturers such as Toshiba and Sharp. Notably, Nintendo entered the video game market during this period alongside its current traditional and electronic toy product lines, producing the series of Color TV-Game consoles in partnership with Mitsubishi.[11]

Growth of video game arcades and the golden age

After the ball-and-paddle market saturation in 1975, game developers began looking for new ideas for games, buoyed by the ability to use programmable microprocessors rather than analog components. Taito designer Tomohiro Nishikado, who had developed Gun Fight previously, was inspired by Atari's Breakout to create a shooting-based game, Space Invaders, first released in Japan in 1978.[14] Space Invaders introduced or popularized several important concepts in arcade video games, including play regulated by lives instead of a timer or set score, gaining extra lives through accumulating points, and the tracking of the high score achieved on the machine. It was also the first game to confront the player with waves of targets that shot back at the player and the first to include background music during game play, albeit a simple four-note loop.[15] Space Invaders was an immediate success in Japan, with some arcades created solely for Space Invaders machines.[14] While not quite as popular in the United States, Space Invaders became a hit as Midway, serving as the North American manufacturer, moved over 60,000 cabinets in 1979.[16]

Space Invaders led off what is considered to be the golden age of arcade games which lasted from 1978 to 1982. Several influential and best-selling arcade games were released during this period from Atari, Namco, Taito, Williams, and Nintendo, including Asteroids (1979), Galaxian (1979), Defender (1980), Missile Command (1980), Tempest (1981), and Galaga (1981). Pac-Man, released in 1980, became a popular culture icon, and a new wave of games appeared that focused on identifiable characters and alternate mechanics such as navigating a maze or traversing a series of platforms. Aside from Pac-Man and its sequel, Ms. Pac-Man (1982), the most popular games in this vein during the golden age were Donkey Kong (1981) and Q*bert (1982).[14] Games like Pac-Man, Donkey Kong and Q*bert also introduced the concept of narratives and characters to video games, which led companies to adopt these later as mascots for marketing purposes.[17][18]

According to trade publication Vending Times, revenues generated by coin-operated video games on location in the United States jumped from $308 million in 1978 to $968 million in 1979 to $2.8 billion in 1980. As Pac Man ignited an even larger video game craze and attracted more female players to arcades, revenues jumped again to $4.9 billion in 1981. According to trade publication Play Meter, by July 1982, total coin-op collections peaked at $8.9 billion, of which $7.7 billion came from video games.[19] Dedicated video game arcades grew during the golden age, with the number of arcades (locations with at least ten arcade games) more than doubling between July 1981 and July 1983 from over 10,000 to just over 25,000.[14][19] These figures made arcade games the most popular entertainment medium in the country, far surpassing both pop music (at $4 billion in sales per year) and Hollywood films ($3 billion).[19]

Introduction of cartridge-based home consoles

Development costs of dedicated game hardware for arcade and home consoles based on discrete component circuitry and application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) with only limited consumer lifespans drove engineers to find alternatives. Microprocessors had dropped far enough in price by 1975 to make these a viable option for developing programmable consoles that could load in game software from a form of swappable media.[20]

The Fairchild Channel F by Fairchild Camera and Instrument was released in 1976. It is the first home console to use programmable ROM cartridges - allowing players to swap games - as well as being the first home console to use a microprocessor which reads instructions from the ROM cartridge. Atari and Magnavox followed suit in 1977 and 1978, respectively, with the release of the Atari Video Computer System (VCS, later known as the Atari 2600) and the Magnavox Odyssey 2, both systems also introducing the use of cartridges. As to complete the Atari VCS quickly, Bushnell sold Atari to Warner Communications $28 million, providing the necessary cash infusion to complete the system's design by the end of 1977.[13] The initial market for these new consoles were initially modest as consumers were still wary after the saturation of dedicated home consoles.[21] However, there was still newfound interest in video games, and new players were drawn to the market, such as Mattel Electronics with the Intellivision.[8] In contrast to the dedicated home Pong consoles, programmable cartridge-based consoles had a higher barrier of entry with the costs of research & development and large-scale production, and fewer manufacturers entered the market during this period.[8]

This new line of consoles had its breakthrough moment when Atari obtained a license from Taito to create the Atari VCS version of the arcade hit Space Invaders, which was released in 1980. Space Invaders quadrupled sales of the Atari VCS, making it the first "killer app" in the video game industry, and the first video game to sell over one million copies and eventually sold over 2.5 million by 1981.[22][23] Atari's consumer sales almost doubled from $119 million to nearly $204 million in 1980 and then exploded to over $841 million in 1981, while sales across the entire video game industry in the United States rose from $185.7 million in 1979 to just over $1 billion in 1981. Through a combination of conversions of its own arcade games like Missile Command and Asteroids and licensed conversions like Defender, Atari took a commanding lead in the industry, with an estimated 65% market share of the worldwide industry by dollar volume by 1981. Mattel settled into second place with roughly 15%-20% of the market, while Magnavox ran a distant third, and Fairchild exited the market entirely in 1979.[8]

Another critical development during this period was the emergence of third-party developers. Atari management did not appreciate the special talent required to design and program a game and treated them like typical software engineers of the period, who were not generally credited for their work or given royalties; this led to Warren Robinett secretly programming his name in one of the earliest Easter eggs into his game Adventure.[24][25] Atari's policies drove four of the company's programmers, David Crane, Larry Kaplan, Alan Miller, and Bob Whitehead, to resign and form their own company Activision in 1979, using their knowledge of developing for the Atari VCS to make and publish their own games. Atari sued to stop Activision's activities, but the companies settled out of court, with Activision agreeing to pay a portion of their game sales as a license fee to Atari.[26] Another group of Atari and Mattel developers left and formed Imagic in 1981, following Activision's model.[27]

Atari's dominance of the market was challenged by Coleco's ColecoVision in 1982. As Space Invaders had done for the Atari VCS, Coleco developed a licensed version of Nintendo's arcade hit Donkey Kong as a bundled game with the system. While the Colecovision only had 17% of the hardware market in 1982 compared to the Atari VCS' share of 58%, it outsold Atari's newer console, the Atari 5200.[28][8]

A few games from this period have been considered milestones in the history of video games, and some of the earliest in popular genres. Robinett's Adventure was inspired from the text adventure Colossal Cave Adventure, and is considered the one of the first graphic adventure and action-adventure games,[29][30] and first cartridge fantasy-themed game.[31] Activision's Pitfall!, beside being one of the more successful third-party games, also established the foundation of side-scrolling platform games.[32] Utopia for the Intellivision was the first city-building game and considered one of the first real-time strategy games.[33][34]

Early hobbyist computer games

The fruit of retail development in early video games appeared mainly in video arcades and home consoles, but at the same time, there was a growing market in home computers. Such home computers were initially a hobbyist activity, with minicomputers such as the Altair 8800 and the IMSAI 8080 released in the early 1970s. Groups like the Homebrew Computer Club in Menlo Park, California envisioned how to create new hardware and software from these minicomputer systems that could eventually reach the home market.[35] Affordable home computers began appearing in the late 1970s with the arrival of the "1977 Trinity": the Commodore PET, the Apple II, and the TRS-80.[36] Most shipped with a variety of pre-made games as well as the BASIC programming language, allowing their owners to program simple games.[37]

Hobbyist groups for the new computers soon formed and PC game software followed. Soon many of these games—at first clones of mainframe classics such as Star Trek, and then later ports or clones of popular arcade games such as Space Invaders, Frogger,[38] Pac-Man (see Pac-Man clones)[39] and Donkey Kong[40]—were being distributed through a variety of channels, such as printing the game's source code in books (such as David Ahl's BASIC Computer Games), magazines (Electronic Games and Creative Computing), and newsletters, which allowed users to type in the code for themselves.[41][42][43]

Whereas hobbyist programming in the United States was seen as a pastime while more players flocked to video game consoles, such "bedroom coders" in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe looked for ways to profit from their work.[44][45] Programmers distributed their works through the physical mailing and selling of floppy disks, cassette tapes, and ROM cartridges.[45] Possibly the first computer game to be sold commercially was Microchess in 1976 by Peter R. Jennings, who also started possibly the first computer game publishing company, Microware.[46] Soon a small cottage industry was formed, with amateur programmers selling disks in plastic bags put on the shelves of local shops or sent through the mail.[45]

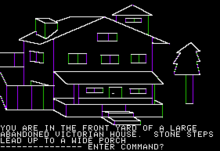

Mainframe and minicomputer games were still largely developed by students and others during this period using the more powerful languages afforded on these systems. A team of MIT students, Tim Anderson, Marc Blank, Bruce Daniels, and Dave Lebling, were inspired by Colossal Cave Adventure to create the text adventure game Zork across 1977 and 1979, and later formed Infocom to republish it commercially in 1980.[47] The first graphical adventure games from Sierra On-Line such as Mystery House, using simple graphics alongside text, also emerged around the same time. Rogue, the namesake of the roguelike genre, was developed in 1980 by Glenn Wichman and Michael Toy who wanted a way to randomize the gameplay of Colossal Cave Adventure.[48]

First handheld LED/VFD/LCD games

Handheld electronic games, using all computerized components but typically using LED or VFD lights for display, first emerged in the early 1970s. LCD displays became inexpensive for consumer products by the mid-1970s and replaced LED and VFD in such games, due to their lower power usage and smaller size. Most of these games were limited to a single game due to the simplicity of the display. Companies like Mattel Electronics, Coleco, Entex Industries, Bandai, and Tomy made numerous electronics games over the 1970s and early 1980s.[49]

Coupled with inexpensive microprocessors, handheld electronic games paved the way for the earliest handheld video game systems by the late 1970s. In 1979, Milton Bradley Company released the first handheld system using interchangeable cartridges, Microvision, which used a built-in LCD matrix screen. While the handheld received modest success in its first year of production, the lack of games, screen size and video game crash of 1983 brought about the system's quick demise.[50]

In 1980, Nintendo released the first of its Game & Watch line, handheld electronic games using LCD screens.[51] Game & Watch spurred dozens of other game and toy companies to make their own portable games, many of which were copies of Game & Watch games or adaptations of popular arcade games. Tiger Electronics borrowed this concept of videogaming with cheap, affordable handhelds and still produces games on this model to the present day.

1980s

The video games industry experienced its first major growing pains in the early 1980s; the lure of the market brought many companies with little experience to try to capitalize on video games, and contributors towards the industry's crash in 1983, decimating the North American market. In the wake of the crash, Japanese companies became the leaders in the industry, and as the industry began to recover, the first major publishing houses appeared, maturing the industry to prevent a similar crash in the future.

Video game crash of 1983

Activision's success as a third-party developer for the Atari VCS and other home consoles inspired other third-party development firms to emerge in the early 1980s; by 1983, at least 100 different companies claimed to be developing software for the Atari VCS.[8] This had been projected to led to a glut in sales, with only 10% of games producing 75% of sales for 1983 based on 1982 estimates.[52] Further, there were questions on the quality of these games. While some of these firms hired experts in game design and programming to build quality games, most were staffed by novice programmers backed by venture capitalists without experience in the area. As a result, the Atari VCS market became watered down with large quantities of poor quality games. These games did not sell well, and retailers discounted their prices to try to get rid of their inventory. This further impacted sales of high-quality games, since consumers would be drawn to purchase bargain-bin priced games over quality games marked at a regular price.[53]

At the end of 1983, several factors, including a market flooded with poor-quality games and loss of publishing control, the lack of consumer confidence in market leader Atari due to the poor performance of several high-profile games, and home computers emerging as a new and more advanced platform for games at nearly the same cost as video game consoles, caused the North American video game industry to experience a severe downturn.[28] The 1983 crash bankrupted several North American companies that produced consoles and games from late 1983 to early 1984. The $3 billion U.S. market in 1983 dropped to $100 million by 1985,[54] while the global video game market estimated at $42 billion in 1982 fell to $14 billion by 1985.[55] Warner Communications sold off Atari to Jack Tramiel in 1984,[56] while Magnavox and Coleco exited the industry.

The crash had some minor effects on Japanese companies with American partners impacted by the crash, but as most of the Japanese companies involved in video games at this point have long histories, they were able to weather the short-term effects. The crash set the stage for Japan to emerge as the leader in the video game industry for the next several years, particularly with Nintendo's introduction of the rebranded Famicom, the Nintendo Entertainment System, back into the U.S. and other Western regions in 1985, maintaining strict publishing control to avoid the same factors that led to the 1983 crash.[57]

The rise of computer games

Second wave of home computers

Following the success of the Apple II and Commodore PET in the late 1970s, a series of cheaper and incompatible home computers emerged in the early 1980s. This second batch included the VIC-20 and Commodore 64; Sinclair ZX80, ZX81 and ZX Spectrum; NEC PC-8000, PC-6001, PC-88 and PC-98; Sharp X1 and X68000; Fujitsu FM Towns, and Atari 8-bit computers, BBC Micro, Acorn Electron, Amstrad CPC, and MSX series. Many of these systems found favor in regional markets.

These new systems helped catalyze both the home computer and game markets, by raising awareness of computing and gaming through their competing advertising campaigns. This was most notable in the United Kingdom where the BBC encouraged computer education and backed the development of the BBC Micro with Acorn.[58] Between the BBC Micro, the ZX Spectrum, and the Commodore 64, a new wave of "bedroom coders" emerged in the United Kingdom and started selling their own software for these platforms, alongside those developed by small professional teams.[59][60][61][62] Small publishing and distribution companies such as Acornsoft and Mastertronic were established to help these individuals and teams to create and sell copies of their games. Ubisoft started out as such a distributor in France in the mid-1980s before they branched out into video game development and publishing.[63] In Japan, systems like the MSX and the NEC PC line were popular, and several development houses emerged developing arcade clones and new games for these platforms. These companies included HAL Laboratory, Square, and Enix, which all later became some of the first third-party developers for the Nintendo Famicom after its release in 1983.[11]

Games from this period include the first Ultima by Richard Garriott and the first Wizardry from Sir-Tech, both fundamental role-playing games on the personal computer. The space trading and combat simulation game Elite by David Braben and Ian Bell introduced a number of new graphics and gameplay features, and is considered one of the first open world and sandbox games.[64] Early installments in a number of long-running franchises such as Castlevania, Metal Gear, Bubble Bobble, Gradius, as well as ports of console games and visual novels appeared on Japanese platforms like the PC88, X68000, and MSX.

Games dominated home computers' software libraries. A 1984 compendium of reviews of Atari 8-bit software used 198 pages for games compared to 167 for all others.[65] By that year the computer game market took over from the console market following the crash of that year; computers offered equal ability and, since their simple design allowed games to take complete command of the hardware after power-on, they were nearly as simple to start playing with as consoles.[citation needed]

Later in the 1980s the next wave of personal computers emerged, with the Amiga and Atari ST in 1985. Both computers had more advanced graphics and sound capabilities than the prior generation of computers, and made for key platforms for video game development, particularly in the United Kingdom. The bedroom coders had since formed development teams and started producing games for these systems professionally. These included Bullfrog Productions, founded by Peter Molyneux, with the release of Populous (the first such god game), DMA Design with Lemmings, Psygnosis with Shadow of the Beast, and Team17 with Worms.[66]

IBM PC compatible

While the second wave of home computer systems flourished in the early 1980s, they remained as closed hardware systems from each other; while programs written in BASIC or other simple languages could be easily copied over, more advanced programs would require porting to meet the hardware requirements of the target system. Separately, IBM released the first of its IBM Personal Computers (IBM PC) in 1981, shipping with the MS-DOS operating system. The IBM PC was designed with an open architecture to allow new components to be added to it, but IBM intended to maintain control on manufacturing with the proprietary BIOS developed for the system.[67] As IBM struggled to meet demand for its PC, other computer manufacturers such as Compaq worked to reverse engineer the BIOS and created IBM PC compatible computers by 1983.[68][69][70][71][72][73] By 1987, IBM PC compatible computers dominated the home and business computer market.[74]

From a video games standpoint, the IBM PC compatible invigorated further game development. A software developer could write to meet IBM PC compatible specifications and not worry about which make or model was being used. While the initial IBM PC supported only monochromatic text games, game developers nevertheless ported mainframe and other simple text games to the PC, such as Infocom with Zork. IBM introduced video display controllers such as the Color Graphics Adapter (CGA) (1981), the Enhanced Graphics Adapter (EGA) (1984) and the Video Graphics Array (VGA) (1987) that expanded the computer's ability to display color graphics, though even with the VGA, these still lagged behind those of the Amiga. The first dedicated sound cards for IBM PC compatibles were released starting in 1987, which provided digital sound conversion input and output far exceeding the computer's internal speakers, and with Creative Labs' Sound Blaster in 1989, the ability to plug in a game controller or similar device.

In 2008, Sid Meier listed the IBM PC as one of the three most important innovations in the history of video games.[75] The advancement in graphic and sound capabilities of the IBM PC compatible led to several influential games from this period. Numerous games that were already made for the earlier home computers were later ported to IBM PC compatible system to take advantage of the larger consumer base, including the Wizardry and Ultima series, with future installments released for the IBM PC. Sierra On-Line's first graphical adventure games launched with the King's Quest series. The first SimCity game by Maxis was released in 1989.[76]

The Apple Macintosh also arrived at this time. In contrast to the IBM PC, Apple maintained a more closed system on the Macintosh, creating a system based around a graphical user interface (GUI)-driven operating system. As a result, it did not have the same market share as the IBM PC compatible, but still had a respectable software library including video games, typically ports from other systems.[67]

The first major video game publishers arose during the 1980s, primarily supporting personal computer games on both IBM PC compatible games and the popular earlier systems along with some console games. Among the major publishers formed at this time included Electronic Arts,[77] and Broderbund, while Sierra On-Line expanded its own publishing capabilities for other developers.[78] Activision, still recovering from the financial impacts of the 1983 video game crash, expanded out to include other software properties for the office, rebranding itself as Mediagenic until 1990.[26]

Early online games

Dial-up bulletin board systems were popular in the 1980s, and sometimes used for online gaming. The earliest such systems were in the late 1970s and early 1980s and had a crude plain-text interface. Later systems made use of terminal-control codes (the so-called ANSI art, which included the use of IBM-PC-specific characters not part of an American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standard) to get a pseudo-graphical interface. Some BBSs offered access to various games which were playable through such an interface, ranging from text adventures to gambling games like blackjack (generally played for "points" rather than real money). On some multiuser BBSs (where more than one person could be online at once), there were games allowing users to interact with one another.

SuperSet Software created Snipes, a text-mode networked computer game in 1983 to test a new IBM Personal Computer–based computer network and demonstrate its abilities. Snipes is officially credited as being the original inspiration for NetWare. It is believed to be the first network game ever written for a commercial personal computer and is recognized alongside 1974 game Maze War (a networked multiplayer maze game for several research machines) and Spasim (a 3D multiplayer space simulation for time shared mainframes) as the precursor to multiplayer games such as 1987's MIDI Maze, and Doom in 1993. In 1995, iDoom (later Kali.net) was created for games that only allowed local network play to connect over the internet. Other services such as Kahn, TEN, Mplayer, and Heat.net soon followed. These services ultimately became obsolete when game producers began including their own online software such as Battle.net, WON and later Steam.

The first user interfaces were plain-text—similar to BBSs—but they operated on large mainframe computers, permitting larger numbers of users to be online at once. By the end of the decade, inline services had fully graphical environments using software specific to each personal computer platform. Popular text-based services included CompuServe, The Source, and GEnie, while platform-specific graphical services included PlayNET and Quantum Link for the Commodore 64, AppleLink for the Apple II and Macintosh, and PC Link for the IBM PC—all of which were run by the company which eventually became America Online—and a competing service, Prodigy. Interactive games were a feature of these services, though until 1987 they used text-based displays, not graphics.

Meanwhile, schools and other institutions gained access to ARPANET, the precursor to the modern internet, in the mid-1980s. While the ARPANET connections were intended for research purposes, students explored ways to use this connectivity for video games. Multi-User Dungeon (MUD) originally was developed by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle at the University of Essex in 1978 as a multiplayer game but limited to the school's mainframe system, but was adapted to use ARPANET when the school gained access to it in 1981, making it the first internet-connected game, and the first such MUD and an early title of massively multiplayer online games.[79]

The home console recovery

8-bit consoles

While the 1983 video game crash devastated the United States market, the Japanese video game sector remained unscathed. That year, Nintendo introduced the Famicom (short for Family Computer), while newcomer Sega used its arcade game background to design the SG-1000. The Famicom quickly became a commercial success in Japan, with 2.5 million consoles sold by the start of 1985. Nintendo wanted to introduce the system into the weak United States market but recognized the market was still struggling from the 1983 crash and video games still had a negative perception there.[80] Working with its Nintendo of America division, Nintendo rebranded the Famicom as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), giving it the appearance of a video cassette recorder rather than a toy-like device, and launched the system in the United States in 1985 with accessories like R.O.B. (Robotic Operating Buddy) to make the system appear more sophisticated than prior home consoles.[81] The NES revitalized the U.S. video game market, and by 1989, the U.S. market has resurged to $5 billion. Over 35 million NES systems were sold in the U.S. through its lifetime, with nearly 62 million units sold globally.[82]

Besides revitalizing the U.S. market, the Famicom/NES console had a number of other long-standing impacts on the video game industry. Nintendo used the razor and blades model to sell the console at near manufacturing cost while profiting from sales of games.[8] Because games sales were critical to Nintendo, it initially controlled all game production, but at requests from companies like Namco and Hudson Soft, Nintendo allowed for third-party developers to create games for the consoles, but strictly controlled the manufacturing process, limited these companies to five games year, and required a 30% licensing fee per game sale, a figure that has been used throughout console development to the present.[83] Nintendo's control of Famicom games led to a bootleg market of unauthorized games from Asian countries. When the NES launched, Nintendo took the lessons it learned from its own bootleg problems with the Famicom, and from the oversaturation of the U.S. market that led to the 1983 crash, and created the 10NES lockout system for NES games that required a special chip to be present in cartridges to be usable on NES systems. The 10NES helped to curb, though did not eliminate, the bootleg market for NES games. Nintendo of America also created the "Nintendo Seal of Approval" to mark games officially licensed by Nintendo and dissuade consumers from purchasing unlicensed third-party games, a symptom of the 1983 crash.[84][57] Within the United States, Nintendo of America set up a special telephone help line to provide players with help with more difficult games and launched Nintendo Power magazine to provide tips and tricks as well as news on upcoming Nintendo games.[85]

Sega's SG-1000 did not fare as well against the Famicom in Japan, but the company continued to refine it, releasing Sega Mark III (also known as the Master System) in 1985. Whereas Nintendo had more success in Japan and the United States, Sega's Mark III sold well in Europe, Oceania, and Brazil.[86][87][88]

Numerous fundamental video game franchises got their start during the Famicom/NES and Mark III/Master System period, mostly out of Japanese development companies. While Mario had already appeared in Donkey Kong and the Game & Watch and arcade game Mario Bros., Super Mario Bros., debuting in 1985, established Mario as Nintendo's mascot as well as the first of the Super Mario franchise.[11] Sega also introduced its first mascot characters, the Opa-Opa ship from Fantasy Zone in 1986 and later replaced by Alex Kidd via Alex Kidd in Miracle World in 1986, though neither gained the popular recognition that Mario had obtained.[89] Other key Nintendo franchises were born out of the games The Legend of Zelda and Metroid, both released in 1986. The formulative center of turn-based computer role-playing games were launched with Dragon Quest (1986) from Chunsoft and Enix, Final Fantasy (1987) from Square, and Phantasy Star (1987) from Sega. Capcom's Mega Man (1987), and Konami's Castlevania (1986) and Metal Gear (1987) also have ongoing franchises, with Metal Gear also considered to be the first mainstream stealth game.[90]

With Nintendo's dominance, Japan became the epicenter of the video game market, as many of the former American manufacturers had exited the market by the end of the 1980s.[91] At the same time, software developers from the home computer side recognized the strength of the consoles, and companies like Epyx, Electronic Arts, and LucasArts began devoting their attention to developing console games[92] By 1989 the market for cartridge-based console games was more than $2 billion, while that for disk-based computer games was less than $300 million.[93]

16-bit consoles

NEC released its PC Engine in 1987 in Japan, rebranded as the TurboGrafx-16 in North America. While the CPU was still an 8-bit system, the TurboGrafx-16 used a 16-bit graphics adapter, and NEC chose to heavily rely on marketing the system as a "16 bit" system to differentiate it from the 8-bit NES. This ploy led to the use of processor bit size as a key factor in marketing video game consoles over the next decade, a period known as the "bit wars".[94]

Sega released its next console, the Mega Drive in Japan in 1988, and rebranded as the Sega Genesis for its North American launch in 1989. Sega wanted to challenge the NES's dominance in the United States with the Genesis, and the initial campaign focused on the 16-bit power of the Genesis over the NES as well as a new line of sports games developed for the console. Failing to make a significant dent in NES' dominance, Sega hired Tom Kalinske to president of Sega of America to run a new campaign. Among Kalinske's changes was a significant price reduction in the console, and the bundling of Sega's newest game Sonic the Hedgehog, featuring Sega's newest mascot of the same name, with the console. Kalinske's changes gave Genesis the edge over the NES by 1991 and led off the start of a console war between Sega and Nintendo. Nintendo's 16-bit console, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) struggled on its initial launch in the United States due to the strength of the Genesis. This console war between Sega and Nintendo lasted until 1994 when Sony Computer Entertainment disrupted both companies with the release of the PlayStation.[95]

Among other aspects of the console war between Sega and Nintendo, this period brought a revolution in sports video games. While these games had existed since the first arcade and console games, their limited graphics required gameplay to be highly simplified. When Sega of America first introduced the Genesis to the United States, it had gotten naming rights from high-profile people in the various sports, such as Pat Riley Basketball and Joe Montana Football, but the games still lacked any complexity. Electronic Arts, under Trip Hawkins, were keen to make a more realistic football game for the Genesis which had the computation capabilities for this, but did not want to pay the high licensing fees that Sega were asking for developing on the Genesis. They were able to secure naming rights for John Madden and reverse engineer the Genesis as to be able to produce John Madden Football, one of the first major successful sports games.[96] Electronic Arts subsequently focused heavily on sports games, expanding into other sports like basketball, hockey and golf.[77]

SNK's Neo-Geo was the most costly console by a wide margin when released in 1990. The Neo-Geo used similar hardware as SNK's arcade machines, giving its games a quality better than other 16-bit consoles, but the system was commercially non-viable. The Neo-Geo was notably the first home console with support for memory cards, allowing players to save their progress in a game, not only at home but also shared with compatible Neo-Geo arcade games.[97]

1990s

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2014) |

The 1990s were a decade of marked innovation in video games. It was a decade of transition from raster graphics to 3D graphics and gave rise to several genres of video games including first-person shooter, real-time strategy, and MMO. Handheld games become more popular throughout the decade, thanks in part to the release of the Game Boy in 1989.[98] Arcade games experienced a resurgence in the early-to-mid-1990s, followed by a decline in the late 1990s as home consoles became more common.

As arcade games declined, however, the home video game industry matured into a more mainstream form of entertainment in the 1990s, but their video games also became more and more controversial because of their violent nature, especially in games of Mortal Kombat, Night Trap, and Doom, leading to the formation of the Interactive Digital Software Association and their rating games by signing them their ESRB ratings since 1994.[99] Major developments of the 1990s include the popularizing of 3D computer graphics using polygons (initially in arcades, followed by home consoles and computers), and the start of a larger consolidation of publishers, higher budget games, increased size of production teams, and collaborations with both the music and motion picture industries. Examples of this include Mark Hamill's involvement with Wing Commander III, the introduction of QSound with arcade system boards such as Capcom's CP System II, and the high production budgets of games such as Squaresoft's Final Fantasy VII and Sega's Shenmue.

Transition to optical media

By end of the 1980s, console games were distributed on ROM cartridges, while PC games shipped on floppy disks, formats that had limitations in storage capacity. Optical media, and specifically the CD-ROM, had been first introduced in the mid-1980s for music distribution and by the early 1990s, both the media and CD drives had become inexpensive to be incorporated into consumer computing devices, including for both home consoles and computers.[100] Besides offering more capacity for gameplay content, optical media made it possible to include long video segments into games, such as full motion video, or animated or pre-rendered cutscenes, allowing for more narrative elements to be added to games.[101]

Prior to the 1990s, some arcade games explored the use of laserdiscs, the most notable being Dragon's Lair in 1983. These games are considered as interactive movies and used full motion video from the laserdisc, prompting the player to respond via controls at the right time to continue the game.[101][102] While these games were popular in the early 1980s, the prohibitive cost of laserdisc technology at the time limited their success. When optical media technology matured and dropped in price by the 1990s, new laserdisc arcade games emerged, such as Mad Dog McCree in 1990.[101] Pioneer Corporation released the LaserActive game console in 1993 that used only laserdiscs, with expansion add-ons to play games from the Sega Genesis and NEC TurboGrafx-16 library, but with a base console price of $1,000 and add-ons at $600, the console did not perform well.[103]

For consoles, optical media were cheaper to produce than ROM cartridges, and batches of CD-ROMs could be produced in a week while cartridges could take two to three months to assemble, in addition to the larger capacity.[104] Add-ons were made for the 16-bit consoles to use CD media, including the PC Engine and the Mega Drive. Other manufacturers made consoles with dual-media, such as NEC's TurboDuo. Philips launched the CD-i in 1990, a console using only optical media, but the unit had limited gaming capabilities and had a limited game library.[105] Nintendo had similarly worked with Sony to develop a CD-based SNES, known as the Super NES CD-ROM, but this deal fell through just prior to its public announcement, and as a result, Sony went on to develop to the PlayStation console released in 1994, that exclusively used optical media.[106] Sony was able to capitalize on how the Japanese market handled game sales in Japan for the PlayStation, by producing only limited numbers of any new CD-ROM game with the ability to rapidly produce new copies of a game should it prove successful, a factor that could not easily be realized with ROM cartridges where due to how fast consumers' tastes changed, required nearly all cartridges expected to sell to be produced upfront. This helped Sony overtake Nintendo and Sega in the 1990s.[107] A key PlayStation game that adapted to the CD format was Final Fantasy VII, released in 1997; Square's developers wanted to transition the series from the series' 2D presentation to using 3D models, and though the series had been exclusive to Nintendo consoles previously, Square determined it would be impractical to use cartridges for distribution while the PlayStation's CD-ROM gave them the space for all the desired content including pre-rendered cutscenes.[108] Final Fantasy VII became a key game, as it expanded the idea of console role-playing games to console game consumers.[101][109] Since the PlayStation, all home gaming consoles have relied on optical media for physical game distribution, outside the Nintendo 64 and Switch.[104]

On the PC side, CD drives were initially available as peripherals for computers before becoming standard components within PCs. CD-ROM technology had been available as early as 1989, with Cyan Worlds' The Manhole being one of the first games distributed on the medium.[101] While CD-ROMs served as a better means to distribute larger games, the medium caught on with the 1993 releases of Cyan's Myst and Trilobyte's The 7th Guest, adventure games that incorporated full motion video segments among fixed pre-rendered scenes, incorporating the CD-ROM medium into the game itself. Both games were considered killer apps to help standardize the CD-ROM format for PCs.[110][111]

Introduction of 3D graphics

In addition to the transition to optical media, the industry as a whole had a major shift toward real-time 3D computer graphics across games during the 1990s. There had been a number of arcade games that used simple wireframe vector graphics to simulate 3D, such as Battlezone, Tempest, and Star Wars. A unique challenge in 3D computer graphics is that real-time rendering typically requires floating-point calculations, which until the 1990s, most video game hardware was not well-suited for. Instead, many games simulated 3D effects such as by using parallax rendering of different background layers, scaling of sprites as they moved towards or away from the player's view, or other rendering methods such as the SNES's Mode 7. These tricks to simulate 3D-rendeder graphics through 2D systems are generally referred to as 2.5D graphics.

True real-time 3D rendering using polygons were soon popularized by Yu Suzuki's Sega AM2 games Virtua Racing (1992) and Virtua Fighter (1993), both running on the Sega Model 1 arcade system board;[112] some of the Sony Computer Entertainment (SCE) staff involved in the creation of the original PlayStation video game console credit Virtua Fighter as inspiration for the PlayStation's 3D graphics hardware. According to SCE's former producer Ryoji Akagawa and chairman Shigeo Maruyama, the PlayStation was originally being considered as a 2D-focused hardware, and it wasn't until the success of Virtua Fighter in the arcades that they decided to design the PlayStation as a 3D-focused hardware.[113] Texture mapping and texture filtering were soon popularized by 3D racing and fighting games.[114]

Home video game consoles such as the PlayStation, the Sega Saturn, and Nintendo 64 also became able to produce texture-mapped 3D graphics. Nintendo had already released Star Fox in 1993 which included the Super FX graphics co-processor chip built into the game cartridge to support polygonal rendering for the SNES, and the Nintendo 64 included a graphics coprocessor on the console directly.

On personal computers, John Carmack and John Romero of id Software had been experimenting with real-time rendering of 3D games through Hovertank 3D and Catacomb 3-D. These led to the release of Wolfenstein 3D in 1992, considered to be the original first-person shooter as it rendered the game's world fast enough to keep up with the player's movements. However, at this point, Wolfenstein 3D's maps were restricted to a single flat level.[115] Improvements would come with Ultima Underworld from Blue Sky Productions, which included floors of different heights and ramps, which took longer to render but was considered acceptable in the role-playing game, and id's Doom, adding lighting effects among other features, but still with limitations that maps were effectively two-dimensional and with most enemies and objects represented by sprites in-game. id had created one of the first game engines that separated the content from the gameplay and rendering layers, and licensed this engine to other developers, resulting in games such as Heretic and Hexen, while other game developers built their own engines based on the concepts of the Doom engine, such as Duke Nukem 3D and Marathon.[116] In 1996, id's Quake was the first computer game with a true 3D game engine with in-game character and object models, and as with the Doom engine, id licensed the Quake engine, leading to a further growth in first-person shooters.[115] By 1997, the first consumer dedicated 3D graphics cards were available on the market driven by the demand for first-person shooters, and numerous 3D game engines were created in the years that followed, including Unreal Engine, GoldSrc, and CryEngine, and establishing 3D as the new standard in most computer video games.[115]

Resurgence and decline of arcades

The 1991 release of Capcom's Street Fighter II popularized competitive one-on-one fighting games.[117] Its success led to a wave of other popular fighting games, such as Mortal Kombat and The King of Fighters. Sports games such as NBA Jam also briefly became popular in arcades during this period.

Further drawing players from arcades were the latest home consoles which were now capable of playing "arcade-accurate" games, including the latest 3D games. Increasing numbers of players waited for popular arcade games to be ported to consoles rather than pumping coins into arcade kiosks.[118] This trend increased with the introduction of more realistic peripherals for computer and console game systems such as force feedback aircraft joysticks and racing wheel/pedal kits, which allowed home systems to approach some of the realism and immersion formerly limited to the arcades.[citation needed] To remain relevant, arcade manufacturers such as Sega and Namco continued pushing the boundaries of 3D graphics beyond what was possible in homes. Virtua Fighter 3 for the Sega Model 3, for instance, stood out for having real-time 3D graphics approaching the quality of CGI full motion video (FMV) at the time.[119] Likewise, Namco released the Namco System 23 to rival the Model 3. By 1998, however, Sega's new console, the Dreamcast, could produce 3D graphics on-par with the Sega Naomi arcade machine. After producing the more powerful Hikaru board in 1999 and Naomi 2 in 2000, Sega eventually stopped manufacturing custom arcade system boards, with their subsequent arcade boards being based on either consoles or commercial PC components.

As patronage for arcades declined, many were forced to close down by the late 1990s and early 2000s. Classic coin-operated games had largely become the province of dedicated hobbyists and as a tertiary attraction for some businesses, such as movie theaters, batting cages, miniature golf courses, and arcades attached to game stores such as F.Y.E. The gap left by the old corner arcades was partly filled by large amusement centers dedicated to providing clean, safe environments and costly game control systems unavailable to home users. These newer arcade games offer driving or other sports games with specialized cockpits integrated into the arcade machine, rhythm games requiring unique controllers like Guitar Freaks and Dance Dance Revolution, and path-based light gun shooting gallery games like Time Crisis.[14] Arcade establishments expanded out to include other entertainment options, such as food and drink, such as the adult-oriented Dave & Buster's and GameWorks franchises, while Chuck E. Cheese's is a similar type of business for families and young children.[14]

Handhelds come of age

In 1989, Nintendo released the cartridge-based Game Boy, the first major handheld game console since the Microvision 10 years earlier. Included with the system was Tetris, which became one of the best-selling video games of all time, drawing many that would not normally play video games to the handheld.[120] Several rival handhelds made their debut in the early 1990s, including the Game Gear and Atari Lynx (the first handheld with color LCD display). Although these systems were more technologically advanced and intended to match the performance of home consoles, they were hampered by higher battery consumption and less third-party developer support. While some of the other systems remained in production until the mid-1990s, the Game Boy and its successive incarnations, the Game Boy Pocket, Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance, were virtually unchallenged for dominance in the handheld market through the 1990s.[121] The Game Boy family also introduced the first installments in the Pokémon series with Pokémon Red and Blue, which remains one of the best-selling video game franchises for Nintendo.[122]

Computer games

With the introduction of 3D graphics and a stronger emphasis on console games, smaller developers, particularly those working on personal computers, were typically shunned by publishers as they had become risk-averse.[123] Shareware, a new method of distributing games from these smaller teams, came out of the early 1990s. Typically a shareware game could be requested by a consumer, which would give them a portion of the game for free outside of shipping charges. If the consumer liked the game, they could then pay for the full game. This model was later expanded to basically include the "demo" version of a game on the insert CD-ROM media for gaming magazines, and then later as digital downloads from various sites like Tucows. id Software is credited with successfully implementing the idea for both Wolfenstein 3D and Doom, which was later used by Apogee (now 3D Realms), Epic MegaGames (now Epic Games).[124]

Several key genres were established during this period. Wolfenstein 3D and Doom are the formative games of the first-person shooter (FPS); the genre itself had gone by "Doom clones" until about 2000 when FPS became the more popular term.[125] Graphic adventure games rose to prominence during this period; including the forementioned Myst and The 7th Guest, several of LucasArts adventure games including the Monkey Island series. However, the adventure game genre was considered dead by the end of the 1990s due to the rising popularity of the FPS and other action genres.[126] The first immersive sims, games that gave the player more agency and choices through flexible game systems, came along after the rise of FPS games, with games like Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss and Thief: The Dark Project. Thief also expanded the idea of stealth games and created the idea of "first person sneaker" games where combat was less a focus.[127]

Real-time strategy games also grew in popularity in 1990s, with seminal games Dune II, Warcraft: Orcs & Humans and Command & Conquer. The first 4X (short for "Explore, Expand, Exploit, Exterminate") strategy games also emerged during this decade, popularized by Sid Meyer's Civilization in 1991. Alone in the Dark in 1992 established many elements of the survival horror genre that were in the console game Resident Evil.[128] Simulation games became popular, including those from Maxis starting with SimCity in 1989, and which culminated with The Sims, which was first released in early 2000.

Online connectivity in computer games has become increasingly important. Building on the growing popularity of the text-based MUDs of the 1980s, graphical MUDs like Habitat used simple graphical interfaces alongside text to visualize the game experience. The first massively multiplayer online role-playing games adapted the new 3D graphics approach to create virtual worlds on screen, starting with Meridian 59 in 1996 and popularized by the success of Ultima Online in 1997 and EverQuest and Asheron's Call in 1999. Online connective play also became important in genres like FPS and RTS, allowing players to connect to human opponents over phone and Internet connectivity. Some companies have created clients to help with connectivity, such as Blizzard Entertainment's Battle.net.

During the 1990s, Microsoft introduced its initial versions of the Microsoft Windows operating system for personal computers, a graphical user interface intended to replace MS-DOS. Game developers found it difficult to program for some of the earlier versions of Windows, as the operating system tended to block their programmatic access to input and output devices. Microsoft developed DirectX in 1995, later integrated into Microsoft Windows 95 and future Windows products, as a set of libraries to give game programmers direct access to these functions. This also helped to provide a standard interface to normalize the wide array of graphics and sound cards available for personal computers by this time, further aiding in ongoing game development.[129]

32- and 64-bit home consoles

Sony's introduction of the first PlayStation in 1994 had hampered both Nintendo and Sega's console war, as well as made it difficult for new companies to enter the market. The PlayStation brought in not only the revolution in CD-ROM media but built-in support for polygonal 3D graphics rendering. Atari attempted to re-enter the market with the 32-bit Atari Jaguar in 1993, but it lacked the game libraries offered by Nintendo, Sega or Sony. The 3DO Company released the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer in 1993, but it also suffered from a higher price compared to other consoles on the market. Sega has placed a great deal of emphasis on the 32-bit Sega Saturn, released in 1994, to follow the Genesis, and though initially fared well in sales with the PlayStation, soon lost ground to the PlayStation's larger range of popular games. Nintendo's next console after the SNES was the Nintendo 64, a 64-bit console with polygonal 3D rendering support. However, Nintendo opted to continue to use the ROM cartridge format, which caused it to lose sales against the PlayStation, and allowing Sony to become the dominant player in the console market by 2000.[130]

Final Fantasy VII, as previously described, was an industry landmark title, and introduced the concept of role-playing games to console players. The origin of music video games emerged with the PlayStation game PaRappa the Rapper in 1997, coupled with the success of arcade games like beatmania and Dance Dance Revolution.[131] Resident Evil and Silent Hill formed the basis of the current survival horror genre.[132] Nintendo had its own critical successes with GoldenEye 007 from Rare, the first first-person shooter for a console that introduced staple features for the genre, and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, one of the most critically acclaimed games of all time.

2000s

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2007) |

The 2000s (decade) showed innovation on both consoles and PCs, and an increasingly competitive market for portable game systems. The impact of wider availability of the Internet led to new gameplay changes, changes in gaming hardware and the introduction of online services for consoles.

The phenomenon of user-created video game modifications (commonly referred to as "mods") for games, one trend that began during the Wolfenstein 3D and Doom-era, continued into the start of the 21st century. The most famous example is that of Counter-Strike; released in 1999, it is still one of the most popular online first-person shooters, even though it was created as a mod for Half-Life by two independent programmers. Eventually, game designers realized the potential of mods and custom content in general to enhance the value of their games, and so began to encourage its creation. Some examples of this include Unreal Tournament, which allowed players to import 3dsmax scenes to use as character models, and Maxis' The Sims, for which players could create custom objects.

In China, video game consoles were banned in June 2000. This has led to an explosion in the popularity of computer games, especially MMOs. Consoles and the games for them are easily acquired however, as there is a robust grey market importing and distributing them across the country. Another side effect of this law has been increased copyright infringement of video games.[133][134]

The changing home console landscape

Sony's dominance of the console market at the start of the 2000s caused a major shift in the market. Sega attempted one more foray into console hardware with the Dreamcast in 1998, notably the first console with a built-in Internet connection for online play. However, Sega's reputation had been tarnished from the Saturn, and with Sony having recently announced its upcoming PlayStation 2, Sega left the hardware console market after the Dreamcast, though remained in the arcade game development as well as developing games for consoles. The Dreamcast's library has some groundbreaking games, notably the Shenmue series which are regarded as a major step forward for 3D open-world gameplay[135] and has introduced the quick time event mechanic in its modern form.[136]

Sony released the PlayStation 2 (PS2) in 2000, the first console to support the new DVD format and with capabilities of playing back DVD movie disks and CD audio disks, as well as playing PlayStation games in a backward compatible mode alongside PS2 games. Nintendo followed the Nintendo 64 with the GameCube in 2001, its first console to use optical discs, though specially formatted for the system. However, a new player entered the console picture at this point, Microsoft with its first Xbox console, also released in 2001. Microsoft had feared that Sony's PS2 would become a central point of electronic entertainment in the living room and squeeze out the PC in the home, and after having recently developing the DirectX set of libraries to standardize game hardware interfaces for Windows-based computers, used this same approach to create the Xbox.[137]

The PS2 remained the leading platform for the first part of the decade, and remains the best-selling home console of all time with over 155 million units sold. This was in part due to a number of critical games released on the system, including Grand Theft Auto III, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty, and Final Fantasy X.[138] The Xbox was able to gain second-place to the PS2 sales, but at a significant lost to Microsoft. However, to Microsoft, the loss was acceptable, as it proved to them they could compete in the console space. The Xbox also introduced Microsoft's flagship title, Halo: Combat Evolved, which relied on the Xbox's built-in Ethernet functionality to support online gameplay.[139]

By the mid-2000s, only Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft were considered major players in the console hardware space. All three introduced their next generation of hardware between 2005 and 2006, starting with Microsoft's Xbox 360 in 2005 and Sony's PlayStation 3 (PS3) in 2006, followed by Nintendo's Wii later that year. The Xbox 360 and PS3 showed a convergence with personal computer hardware: both consoles shipped with support for high-definition graphics, higher-density optical media like Blu-rays, internal hard drives for storage of games, and had built-in Internet connectivity. Microsoft and Sony also had developed online digital services, Xbox Live and PlayStation Network that helped players connect to friends online, matchmake for online games, and purchase new games and content from online stores. In contrast, the Wii was designed as part of a new blue ocean strategy by Nintendo after poor sales of the GameCube. Instead of trying to compete feature for feature with Microsoft and Sony, Nintendo designed the Wii to be a console for innovative gameplay rather than high performance, and created the Wii Remote, a motion detection-based controller. Gameplay designed around the Wii Remote provided instant hits, such as Wii Sports, Wii Sports Resort, and Wii Fit, and the Wii became one of the fastest selling consoles in its few years.[140] The success of the Wii's motion controls partially led to Microsoft and Sony to develop their own motion-sensing control systems, the Kinect and the PlayStation Move.

A major fad in the 2000s was the rapid rise and fall of rhythm games which use special game controllers shaped like musical instruments such as guitars and drums to match notes while playing licensed songs. Guitar Hero, based on the arcade game Guitar Freaks, was developed by Harmonix and published by Red Octane in 2005 on the PS2, and was a modest success. Activision acquired Red Octane and gained the publishing rights to the series, while Harmonix was purchased by Viacom, where they launched Rock Band, a similar series but adding in drums and vocals atop guitars. Rhythm games because a highly-popular property second only to action games, representing 18% of the video game market in 2008, and drew other publishers to the area as well.[141] While Harmonix approached the series by adding new songs as downloadable content, Activision focused on releasing new games year after year in the Guitar Hero series; by 2009, they had six different Guitar Hero-related games planned for the year. The saturation of the market, in addition to the fad of these instrument controllers, quickly caused the $1.4 billion market in 2008 to fall by 50% in 2009.[142] By 2011, Activision had stopped publishing Guitar Hero games (though returned one time in 2015 with Guitar Hero Live), while Harmonix has continued to develop Rock Back after a hiatus between 2013 and 2015.

Nintendo still dominated the handheld games market during this period. The Game Boy Advance, released in 2001, maintained Nintendo's market position with a high-resolution, full-color LCD screen and 32-bit processor allowing ports of SNES games and simpler companions to N64 and GameCube games.[143] The next two major handhelds, the Nintendo DS and Sony's PlayStation Portable (PSP) within a month of each other in 2004. While the PSP boasted superior graphics and power, following a trend established since the mid-1980s, Nintendo gambled on a lower-power design but featuring a novel control interface. The DS's two screens, with one being a touch-sensitive screen, proved extremely popular with consumers, especially young children and middle-aged gamers, who were drawn to the device by Nintendo's Nintendogs and Brain Age series respectively, as well as introducing localized Japanese visual novel-type games such as the Ace Attorney and Professor Layton series to the Western regions. The PSP attracted a significant portion of veteran gamers in North America and was very popular in Japan; its ad-hoc networking capabilities worked well within the urban Japanese setting, which directly contributed to spurring the popularity of Capcom's Monster Hunter series.[144]

MMOs, esports, and online services

As affordable broadband Internet connectivity spread, many publishers turned to online games as a way of innovating. Massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) featured significant PC games like RuneScape, EverQuest, and Ultima Online, with World of Warcraft as one of the most successful.[145] Other large-scale massively-multiplayer online games also were released, such as Second Life which focused mostly on social interactions with virtual player avatars and user creations, rather than any gameplay elements.[146]

Historically, console-based MMORPGs have been few due to the lack of bundled Internet connectivity options for the platforms. This made it hard to establish a large enough subscription community to justify the development costs. The first significant console MMORPGs were Phantasy Star Online on the Sega Dreamcast (which had a built in modem and aftermarket Ethernet adapter), followed by Final Fantasy XI for the Sony PlayStation 2 (an aftermarket Ethernet adapter was shipped to support this game).[145] Every major platform released since the Dreamcast has either been bundled with the ability to support an Internet connection or has had the option available as an aftermarket add-on. Microsoft's Xbox also had its own online service called Xbox Live. Xbox Live was a huge success and proved to be a driving force for the Xbox with games like Halo 2 that were highly popular.