Playwright

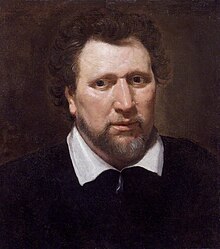

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between characters and is intended for theatrical performance rather than just reading. Ben Jonson coined the term "playwright" and is the first person in English literature to refer to playwrights as separate from poets.

The earliest playwrights in Western literature with surviving works are the Ancient Greeks. William Shakespeare is amongst the most famous playwrights in literature, both in England and across the world.

Etymology

[edit]The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause").[1] The word wright is an archaic English term for a craftsperson or builder (as in a wheelwright or cartwright).[2] The words combine to indicate a person who has "wrought" words, themes, and other elements into a dramatic form—a play. (The homophone with "write" is coincidental.)

The first recorded use of the term "playwright" is from 1605,[3] 73 years before the first written record of the term "dramatist".[4] It appears to have been first used in a pejorative sense by Ben Jonson[5] to suggest a mere tradesman fashioning works for the theatre.

Jonson uses the word in his Epigram 49, which is thought to refer to John Marston[6] or Thomas Dekker:[7]

- Epigram XLIX — On Playwright

- PLAYWRIGHT me reads, and still my verses damns,

- He says I want the tongue of epigrams ;

- I have no salt, no bawdry he doth mean ;

- For witty, in his language, is obscene.

- Playwright, I loath to have thy manners known

- In my chaste book ; I profess them in thine own.

Jonson described himself as a poet, not a playwright, since plays during that time were written in meter and so were regarded as the province of poets. This view was held as late as the early 19th century. The term "playwright" later again lost this negative connotation.

History

[edit]Early playwrights

[edit]The earliest playwrights in Western literature with surviving works are the Ancient Greeks. These early plays were for annual Athenian competitions among play writers[8] held around the 5th century BC. Such notables as Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes established forms still relied on by their modern counterparts. We have complete texts extant by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides.[9][a] The origins of Athenian tragedy remain obscure, though by the 5th century it was institutionalised in competitions (agon) held as part of festivities celebrating Dionysos (the god of wine and fertility).[10] As contestants in the City Dionysia's competition (the most prestigious of the festivals to stage drama), playwrights were required to present a tetralogy of plays (though the individual works were not necessarily connected by story or theme), which usually consisted of three tragedies and one satyr play.[11][b]

For the ancient Greeks, playwriting involved poïesis, "the act of making". This is the source of the English word poet.

Despite Chinese Theatre having performers dated back to the 6th century BC with You Meng, their perspective of theatre was such that plays had no other role than "performer" or "actor", but given that the performers were also the ones who invented their performances, they could be considered a form of playwright.[12]

Outside of the Western world there is Indian classical drama, with one of the oldest known playwrights being Śudraka, whose attributed plays can be dated to the second century BC.[13] The Nāṭya Shāstra, a text on the performing arts from between 500BC-500AD, categorizes playwrights as being among the members of a theatre company, although playwrights were generally the highest in social status, with some being kings.[14]

Aristotle's Poetics techniques

[edit]In the 4th century BCE, Aristotle wrote his Poetics, in which he analyzed the principle of action or praxis as the basis for tragedy.[15] He then considered elements of drama: plot (μύθος mythos), character (ἔθος ethos), thought (dianoia), diction (lexis), music (melodia), and spectacle (opsis). Since the myths on which Greek tragedy were based were widely known, plot had to do with the arrangement and selection of existing material.[15] Character was determined by choice and by action. Tragedy is mimesis—"the imitation of an action that is serious". He developed his notion of hamartia, or tragic flaw, an error in judgment by the main character or protagonist, which provides the basis for the "conflict-driven" play.[15]

Medieval

[edit]There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by Adam de la Halle in 1276. It contains satirical scenes and folk material such as faeries and other supernatural occurrences. Farces also rose dramatically in popularity after the 13th century. The majority of these plays come from France and Germany and are similar in tone and form, emphasizing sex and bodily excretions.[16]

The best known playwright of farces is Hans Sachs (1494–1576) who wrote 198 dramatic works. In England, The Second Shepherds' Play of the Wakefield Cycle is the best known early farce. However, farce did not appear independently in England until the 16th century with the work of John Heywood (1497–1580).

Playwright William Shakespeare remains arguably the most influential writer in the English language, and his works continue to be studied and reinterpreted. Most playwrights of the period typically collaborated with others at some point, as critics agree Shakespeare did, mostly early and late in his career.[17] His plays have been translated into every major living language and are performed more often than those of any other playwright.[18]

In England, after the interregnum, and Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, there was a move toward neoclassical dramaturgy. Between the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and the end of the 17th century, classical ideas were in vogue. As a result, critics of the time mostly rated Shakespeare below John Fletcher and Ben Jonson.[19] This period saw the first professional woman playwright, Aphra Behn.

As a reaction to the decadence of Charles II era productions, sentimental comedy grew in popularity. Playwrights like Colley Cibber and Richard Steele believed that humans were inherently good but capable of being led astray.[20][21]

Neo-classical theory

[edit]

The Italian Renaissance brought about a stricter interpretation of Aristotle, as this long-lost work came to light in the late 15th century. The neoclassical ideal, which was to reach its apogee in France during the 17th century, dwelled upon the unities, of action, place, and time. This meant that the playwright had to construct the play so that its "virtual" time would not exceed 24 hours, that it would be restricted to a single setting, and that there would be no subplots. Other terms, such as verisimilitude and decorum, circumscribed the subject matter significantly. For example, verisimilitude limits of the unities. Decorum fitted proper protocols for behavior and language on stage.

In France, contained too many events and actions, thus, violating the 24-hour restriction of the unity of time. Neoclassicism never had as much traction in England, and Shakespeare's plays are directly opposed to these models, while in Italy, improvised and bawdy commedia dell'arte and opera were more popular forms.

One structural unit that is still useful to playwrights today is the "French scene", which is a scene in a play where the beginning and end are marked by a change in the makeup of the group of characters onstage rather than by the lights going up or down or the set being changed.[22]

Notable playwrights:

- Pierre Corneille (1606–84)

- Molière (1622–73)

- Jean Racine (1639–99)

Cretan Renaissance theatre

[edit]Greek theater was alive and flourishing on the island of Crete. During the Cretan Renaissance two notable Greek playwrights Georgios Chortatzis and Vitsentzos Kornaros were present in the latter part of the 16th century.[23]

19th century

[edit]The plays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller, and other Sturm und Drang playwrights inspired a growing faith in feeling and instinct as guides to moral behavior and were part of the German romanticism movement. Aleksandr Ostrovsky was Russia's first professional playwright).

Contemporary playwrights in the United States

[edit]

Author and playwright Agatha Christie wrote The Moustrap, a murder mystery play which is the longest-running West End show, it has by far the longest run of any play in the world, with its 29,500th performance having taken place as of February 2024.[24]

Contemporary playwrights in the United States are affected by recent declines in theatre attendance.[25] No longer the only outlet for serious drama or entertaining comedies, theatrical productions must use ticket sales as a source of income, which has caused many of them to reduce the number of new works being produced. For example, Playwrights Horizons produced only six plays in the 2002–03 seasons, compared with thirty-one in 1973–74.[26] Playwrights commonly encounter difficulties in getting their shows produced and often cannot earn a living through their plays alone, leading them to take up other jobs to supplement their incomes.[27]

Many playwrights are also film makers. For instance, filmmaker Morgan Spurlock began his career as a playwright, winning awards for his play The Phoenix at both the New York International Fringe Festival in 1999 and the Route 66 American Playwriting Competition in 2000.[28]

New play development

[edit]Today, theatre companies have new play development programs meant to develop new American voices in playwriting. Many regional theatres have hired dramaturges and literary managers in an effort to showcase various festivals for new work, or bring in playwrights for residencies.[29] Funding through national organizations, such as the National Endowment for the Arts[30] and the Theatre Communications Group, encouraged the partnerships of professional theatre companies and emerging playwrights.[31]

Playwrights will often have a cold reading of a script in an informal sitdown setting, which allows them to evaluate their own plays and the actors performing them. Cold reading means that the actors haven't rehearsed the work, or may be seeing it for the first time, and usually, the technical requirements are minimal.[32] The O'Neill Festival[33] offers summer retreats for young playwrights to develop their work with directors and actors.

Playwriting collectives like 13P and Orbiter 3[34] gather members together to produce, rather than develop, new works. The idea of the playwriting collective is in response to plays being stuck in the development process and never advancing to production.[35]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The theory that Prometheus Bound was not written by Aeschylus adds a fourth, anonymous playwright to those whose work survives.

- ^ Exceptions to this pattern were made, as with Euripides' Alcestis in 438 BC. There were also separate competitions at the City Dionysia for the performance of dithyrambs and, after 488–7 BC, comedies.

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of PLAY". www.merriam-webster.com. 2024-04-28. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Definition of WRIGHT". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Definition of playwright". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Definition of dramatist". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2018.

- ^ "Jonson, Ben, The Works of Ben Jonson, Boston: Phillips, Sampson and Co., 1853. page 788". Luminarium: Anthology of English Literature. 2003-08-10. Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ^ Allen, Morse S. (1920). The satire of John Marston. Columbis, Ohio: The F. J. Heer Printing Co. p. 75.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Jonson, Ben; Cain, Thomas Grant Stevens; Connolly, Ruth (2022). The poems of Ben Jonson. Longman annotated English poets. Abingdon, Oxon New York: Routledge. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-315-69619-5.

- ^ Fraser, Neil. playwright History Explained, The Cowood Press, 2004, page 11

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15).

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 13–15) and Brown (1995, 441–447).

- ^ Brown (1995, 442) and Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–17).

- ^ Ye, Tan (2008). Historical dictionary of Chinese theater. Historical dictionaries of literature and the arts. Lanham, Md: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5514-4. OCLC 182662750. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Stoneman, Richard (2019). The Greek experience of India: from Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15403-9. OCLC 1032723070. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-30.

- ^ Richmond, Farley P., ed. (1993). Indian theatre: traditions of performance. Performing arts series. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-0981-9.

- ^ a b c Aristotle (1902). Poetics. Translated by Butcher, S.H. (3rd ed.). Macmillan. p. 45.

- ^ Brockett and Hildy (2003, 96)

- ^ Thomson, Peter (2003). "Conventions of Playwriting". Shakespeare: An Oxford Guide. Oxford University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-19-924522-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Craig, Leon Harold (2003). Of Philosophers and Kings: Political Philosophy in Shakespeare's Macbeth and King Lear. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-8020-8605-1.

- ^ Grady, Hugh (2001). "Shakespeare criticism, 1600–1900". The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-139-00010-9.

- ^ Campbell, William. "Sentimental Comedy in England and on the Continent". The Cambridge History of English and American Literature. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ Harman, William (2011). A Handbook to Literature (12 ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-0205024018.

- ^ George, Kathleen (1994) Playwriting: The First Workshop, Focal Press, ISBN 978-0-240-80190-2, p. 154.

- ^ Robert Browning (1983). Medieval and Modern Greek. Cambridge University Press. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-521-29978-0.

- ^ "Celebrating 29,500 perfoemnces". Agatha Christie's The Mousetrap. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Pierson, Alexandra; Merrill, Amelia; Coutinho, Gabriela Furtado; Pierce, Jerald Raymond; Sims, Joseph; Weinert-Kendt, Rob (2023-07-24). "Theatre in Crisis: What We're Losing, and What Comes Next". AMERICAN THEATRE. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis (2003-05-21). "The Plays What They Wrote: The Best Scripts Not Yet Mounted on a New York Stage". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ^ London, Todd (2009). Outrageous Fortune: The Life and Times of the New American Play. Theatre Development Fund.

- ^ Roberts, Genevieve (March 31, 2012). "Morgan Spurlock: 'I was doing funny walks around the house aged six'". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- ^ Haimbach, Brian Prince (2006). Contemporary new play development. University of Georgia.

- ^ "GRANTS FOR ARTS PROJECTS: Theater". www.arts.gov. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Home - Edgerton Foundation New Play Awards". circle.tcg.org. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "What is a Cold Reading? Do I memorize my lines?". Kid's Top Hollywood Acting Coach. 26 October 2022. Archived from the original on 27 May 2024. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ "Young Playwrights Festival | Eugene O'Neill Theater Center". theoneill. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "Orbiter 3". Orbiter 3. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

- ^ "13 Playwrights Is Preparing To Implode". HuffPost. 2012-07-26. Archived from the original on 2024-05-27. Retrieved 2024-04-29.

External links

[edit] Learning materials related to Collaborative play writing at Wikiversity

Learning materials related to Collaborative play writing at Wikiversity The dictionary definition of playwright at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of playwright at Wiktionary Media related to Playwrights at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Playwrights at Wikimedia Commons