History of accounting

The history of accounting or accountancy can be traced to ancient civilizations.[1][2][3]

The early development of accounting dates to ancient Mesopotamia, and is closely related to developments in writing, counting and money[1][4][5] and early auditing systems by the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians.[2] By the time of the Roman Empire, the government had access to detailed financial information.[6]

In India, Chanakya wrote a manuscript similar to a financial management book, during the period of the Mauryan Empire. His book Arthashastra contains few detailed aspects of maintaining books of accounts for a sovereign state.

The Italian Luca Pacioli, recognized as The Father of accounting and bookkeeping was the first person to publish a work on double-entry bookkeeping, and introduced the field in Italy.[7][8]

The modern profession of the chartered accountant originated in Scotland in the nineteenth century. Accountants often belonged to the same associations as solicitors, who often offered accounting services to their clients. Early modern accounting had similarities to today's forensic accounting. Accounting began to transition into an organized profession in the nineteenth century,[9] with local professional bodies in England merging to form the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales in 1880.[10]

Ancient history

[edit]

Early development of accounting

[edit]Accounting records dating back more than 7,000 years have been found in Mesopotamia,[11] and documents from ancient Mesopotamia show lists of expenditures, and goods received and traded.[1] The development of accounting, along with that of money and numbers, may be related to the taxation and trading activities of temples:

"another part of the explanation as to why accounting employs the numerical metaphor is [...] that money, numbers and accounting are interrelated and, perhaps, inseparable in their origins: all emerged in the context of controlling goods, stocks and transactions in the temple economy of Mesopotamia."[1]

The early development of accounting was closely related to developments in writing, counting, and money. In particular, there is evidence that a key step in the development of counting—the transition from concrete to abstract counting—was related to the early development of accounting and money and took place in Mesopotamia[1]

Other early accounting records were also found in the ruins of ancient Babylon, Assyria and Sumer, which date back more than 7,000 years. The people of that time relied on primitive accounting methods to record the growth of crops and herds. Because there was a natural season to farming and herding, it was easy to count and determine if a surplus had been gained after the crops had been harvested or the young animals weaned.[11]

Expansion of the role of the accountant

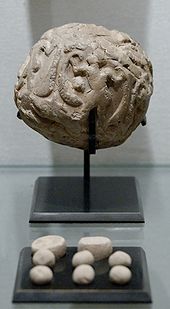

[edit]Between the 4th millennium BC and the 3rd millennium BC, the ruling leaders and priests in ancient Iran had people oversee financial matters. In Godin Tepe (گدین تپه) and Tepe Yahya (تپه يحيی), cylindrical tokens that were used for bookkeeping on clay scripts were found in buildings that had large rooms for storage of crops. In Godin Tepe's findings, the scripts only contained tables with figures, while in Tepe Yahya's findings, the scripts also contained graphical representations.[4] The invention of a form of bookkeeping using clay tokens represented a huge cognitive leap for mankind.[5]

During the 2nd millennium BC,[12] the expansion of commerce and business expanded the role of the accountant. The Phoenicians invented a phonetic alphabet "probably for bookkeeping purposes", based on the Egyptian hieratic script, and there is evidence that an individual in ancient Egypt held the title "comptroller of the scribes". There is also evidence for an early form of accounting in the Old Testament; for example the Book of Exodus describes Moses engaging Ithamar to account for the materials that had been contributed towards the building of the tabernacle.[2]

By about the 4th century BC, the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians had auditing systems for checking movement in and out of storehouses, including oral "audit reports", resulting in the term "auditor" (from Latin: audire, to hear). The importance of taxation had created a need for the recording of payments, and the Rosetta Stone also includes a description of a tax revolt.[2]

Roman Empire

[edit]

By the reign of Emperor Augustus (27 BC - AD 14), the Roman government had access to detailed financial information, as evidenced by the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Latin: "The Deeds of the Divine Augustus"). The inscription was an account to the Roman people of Augustus' stewardship, and listed and quantified his public expenditure, including distributions to the people, grants of land or money to army veterans, subsidies to the aerarium (treasury), building of temples, religious offerings, and expenditures on theatrical shows and gladiatorial games, covering a period of about forty years. The scope of the accounting information at the emperor's disposal suggests that its purpose encompassed planning and decision-making.[6]

The Roman historians Suetonius and Cassius Dio record that in 23 BC, Augustus prepared a rationarium (account) which listed public revenues, and the amounts of cash in the aerarium (treasury), in the provincial fisci (tax officials), and in the hands of the publicani (public contractors); and that it included the names of the freedmen and slaves from whom a detailed account could be obtained. The closeness of this information to the executive authority of the emperor is attested by Tacitus' statement that it was written out by Augustus himself.[13]

Records of cash, commodities, and transactions were kept scrupulously by military personnel of the Roman army. An account of small cash sums received over a few days at the fort of Vindolanda circa AD 110 shows that the fort could compute revenues in cash on a daily basis, perhaps from sales of surplus supplies or goods manufactured in the camp, items dispensed to slaves such as cervesa (beer) and clavi caligares (nails for boots), as well as commodities bought by individual soldiers. The basic needs of the fort were met by a mixture of direct production, purchase and requisition; in one letter, a request for money to buy 5,000 modii (measures) of braces (a cereal used in brewing) shows that the fort bought provisions for a considerable number of people.[14]

The Heroninos Archive is the name given to a huge collection of papyrus documents, mostly letters, but also including a fair number of accounts, which come from Roman Egypt in the 3rd century AD. The bulk of the documents relate to the running of a large, private estate.[15] It is named after Heroninos because he was phrontistes (Koine Greek: manager) of the estate, which had a complex and standardised system of accounting which was followed by all its local farm managers.[16] Each administrator on each sub-division of the estate drew up his own little accounts, for the day-to-day running of the estate, payment of the workforce, production of crops, the sale of produce, the use of animals, and general expenditure on the staff. This information was then summarized on pieces of papyrus scroll into one big yearly account for each particular sub-division of the estate. Entries were arranged by sector, with cash expenses and gains extrapolated[extracted?] from all the different sectors. Accounts of this kind gave the owner the opportunity to take better economic decisions because the information was purposefully selected and arranged.[17]

Medieval and Renaissance periods

[edit]Double-entry bookkeeping

[edit]In eighth century Persia, scholars were confronted with the Qur’an's requirement that Muslims keep records of their indebtedness as a part of their obligation to account to God on all matters of their life. This became particularly difficult when it came to inheritance, which demanded detailed accounting for the estate after death of an individual. The assets remaining after the payment of funeral expenses and debts were allocated to every member of the family in fixed shares, and included wives, children, fathers and mothers. This required extensive use of ratios, multiplication and division that depended on the mathematics of Hindu-Arabic numerals.

The inheritance mathematics were solved by a system developed by the medieval Islamic mathematician Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (known in Europe as Algorithmi from which we derive "algorithm"). Al-Khwarizmi's opus “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing” established the mathematics of algebra, with the last chapter devoted to the double-entry bookkeeping required for solution to the Islamic inheritance allocations.[18] Al Khwarizmi's work was widely circulated, at a time that there was substantial active discourse and trade between Arabic, Jewish and European scholars. It was taught in the learning centers of Al-Andalus in Iberia, and from the tenth century forward, slowly found its way into European banking, which began slipping Hindo-Arabic numerals into accounting books, despite their prohibition as sinful by the medieval church. Bankers in Cairo, for example, used a double-entry bookkeeping system which predated the known usage of such a form in Italy, and whose records remain from the 11th century AD, found amongst the Cairo Geniza.[19] Fibonacci included double-entry and Hindo-Arabic numerals in his Liber Abaci which was widely read in Italy and Europe.

Al-Khwarizmı's book introduced al-jabr meaning "restoration” (which European translated as "algebra") to its inheritance accounting, leading to three fundamental accounting - algebreic concepts:

- Debits = Credits: algebraic manipulations on the left-hand and right-hand sides of an equal sign had to "balance" or they were in error. This is the algebraic equivalent of double-entries "bookkeeping equation" for error control.

- Real accounts: These included assets for tracking wealth, weighed against liabilities from the claims of others against that wealth, and the difference which is the owner's net wealth, or owner's equity.This was al-Khwarizmi's "basic accounting equation".

- Nominal accounts: These tracked activity that affected wealth, and the "restoration" into the real accounts reflected accounting's closing process and the calculation of the owner's increment in wealth—net income.

Algebra balances and restores formulas on the left and right of an equal sign. Double-entry bookkeeping similarly balances and restores debit and credit totals around an equal sign. Accounting is the balancing and restoration of algebra applied to wealth accounting.[20]

In 756, the Abbasid caliph Al-Mansur sent scholars, merchants and mercenaries to support the Tang dynasty's Dukes of Li to thwart the An Shi Rebellion. The Abbasids and Tangs established an alliance, where the Abbasids were known as the Black-robed Arabs. The Tang dynasty's extensive conquests and polyglot court required new mathematics to manage a complex bureaucratic system of tithes, corvee labor and taxes. Abbasid scholars implemented their algebraic double-entry bookkeeping into operations of many of the Tang ministries. The Tang dynasty expanded their maritime presence across the Indian Ocean, Persian Gulf, and Red Sea, and up the Euphrates River.[21] On land they conquered much of what is today's China.

The Tangs invented paper currency, with roots in merchant receipts of deposit as merchants and wholesalers. The Tang's money certificates, colloquially called “flying cash” because of its tendency to blow away, demanded much more extensive accounting for transactions. A fiat currency only drives value from its history of transactions, starting with government issue, unlike gold and specie. Paper money was much more portable than heavy metallic specie, and the Tang assured its universal usage under threat of penalties and possibly execution for using anything else.

The Tangs were great innovators in the widespread use of paper for accounting books, and transaction documents. They developed the 8th-century Chinese printing techniques involving chiseling an entire page of text into a wood block backwards, applying ink, and printing pages by inventing early movable type, including characters chiseled in wood and the creation of ceramic print blocks. Tang science, culture, manners and clothing were widely imitated across Asia. Japan's traditional dress, as well as customs like sitting on the floor for meals, were borrowed from the Tangs. Imperial ministries adopted the Tang's double-entry bookkeeping for administration of taxes and expenditures. The Goryeo kingdom (the modern name "Korea" derives from Goryeo) donned the imperial yellow clothing of the Tangs, used the Three Departments and Six Ministries imperial system of the Tang dynasty and had its own "microtributary system" that included the Jurchen tribes of north China. The Tang's double-entry bookkeeping was essential to managing the complex bureaucracies surrounding Goryeo tribute and taxation.[22]

Later dispersion of knowledge of double-entry can be attributed to the rise of Genghis Khan and later his grandson Kublai Khan who were deeply influenced by the bureaucracy of the Tang dynasty. The accountants were the first to enter a city conquered by Mongols, tallying up the total wealth of the city, from which the Mongols took 10%, to be allocated between the troops. Cities were conquered, then encouraged to remain going-concerns. Double entry bookkeeping played an important role in assuring the Mongols were fully informed about taxes and expenditure.[22]

Ratios, division and multiplication were difficult with Roman numerals, and were achieved through a method called "doubling."[22] Similarly, addition and subtraction involved an error-prone rearranging of Roman numerals. None of this lent itself to double-entry bookkeeping, an as a result, medieval Europe lagged Eastern and Central Asia in adopting double-entry bookkeeping. Hindu-Arabic numerals were known in Europe, but those who used them were considered in league with the devil. The prohibition of Hindu-Arabic mathematics was incorporated into statutes proscribing the use of anything but Roman numerals. That such statutes were necessary is an indication of the attractiveness to merchants of double-entry bookkeeping. Fibonacci’s book Liber Abaci disseminated knowledge about double-entry and Hindu-Arabic numerals widely to merchants and bankers, but because editions were hand copied, only a small group of people actually had access to its knowledge, primarily Italians. The earliest extant evidence of full double-entry bookkeeping appears in the Farolfi ledger of 1299–1300.[7] Giovanno Farolfi & Company, a firm of Florentine merchants headquartered in Nîmes, acted as moneylenders to the Archbishop of Arles, their most important customer.[23] The oldest discovered record of a complete double-entry system is the Messari (Italian: Treasurer's) accounts of the city of Genoa in 1340. The Messari accounts contain debits and credits journalised in a bilateral form and carry forward balances from the preceding year, and therefore enjoy general recognition as a double-entry system.[24]

The Renaissance

[edit]The Vatican, and the Italian banking centers of Genoa, Florence and Venice grew wealthy in the 14th century. Their operations recorded transactions, made loans, issued receipts and other modern banking activities. Fibbonaci ’s Liber Abaci was widely read in Italy, and the Italian Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici introduced double-entry bookkeeping for the Medici bank in the 14th century. By the end of the 15th century, merchant ventures in Venice used this system widely. The Vatican was an early customer for German printing technology, which they used to churn out indulgences. Printing reached a wider audience with widely available reading glasses from Venetian glassmakers (medieval Europeans tended to be far-sighted, which made reading difficult before spectacles). Italy became a center for European printing, particularly with the rise of Aldine Press editions of classics in Greek and Latin.[22]

It was in this environment that a close friend of Leonardo da Vinci, the itinerant tutor, Luca Pacioli published a book not in Greek or Latin, but in a language that merchants understood well -- Italian vernacular. Pacioli received an abbaco education, i.e., education in the vernacular rather than Latin and focused on the knowledge required of merchants. His pragmatic orientation, widespread promotion by his friend da Vinci, and use of vernacular Italian assured that his 1494 publication, Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita (Everything About Arithmetic, Geometry and Proportion) would become wildly popular. Pacioli's book explained the Hindu-Arabic numerals, new developments in mathematics, and the system of double-entry was popular with the increasingly influential merchant class. In contrast to scholarly abstracts in Latin, Pacioli's vernacular text was accessible to the common man, and addressed the needs of businessmen and merchants.[22] His book remained in print for nearly 400 years.

Luca's book popularized the words “credre” means “to entrust” and “debere” means “to owe”—the origin of the use of the words "debit" and "credit" in accounting, but goes back to the days of single-entry bookkeeping, which had as its chief objective keeping track of amounts owed by customers (debtors) and amounts owed to creditors. Debit in Latin means "he owes" and credit in Latin means "he trusts".[25]

Ragusan economist Benedetto Cotrugli's 1458[26] treatise Della mercatura e del mercante perfetto contained the earliest known[27] manuscript of a double-entry bookkeeping system. But his manuscript was not published until 1573.[28]

Luca Pacioli's Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalità (early Italian: "Review of Arithmetic, Geometry, Ratio and Proportion") was first printed and published in Venice in 1494. It included a 27-page treatise on bookkeeping, "Particularis de Computis et Scripturis" (Latin: "Details of Calculation and Recording"). Pacioli wrote primarily for, and sold mainly to, merchants who used the book as a reference text, as a source of pleasure from the mathematical puzzles it contained, and to aid the education of their sons. His work represents the first known printed treatise on bookkeeping; and it is widely believed to be the forerunner of modern bookkeeping practice. In Summa de arithmetica, Pacioli introduced symbols for plus and minus for the first time in a printed book, symbols which became standard notation in Italian Renaissance mathematics. Summa de arithmetica was also the first known book printed in Italy to contain algebra.[29]

So although Cotrugli was first, Pacioli was first to publication. Indeed, at the time of writing his work in 1494, Pacioli was aware of Cotrugli's efforts and credited Cortrugli with the origination of the double entry book keeping system.[30][31]

So although Luca Pacioli did not invent double-entry bookkeeping,[32] his 27-page treatise on bookkeeping is a seminal work because of its wide circulation and the fact that it was printed in the vernacular Italian language.[33]

Pacioli saw accounting as an ad-hoc ordering system devised by the merchant. Its regular use provides the merchant with continued information about his business, and allows him to evaluate how things are going and to act accordingly. Pacioli recommends the Venetian method of double-entry bookkeeping above all others. Three major books of account are at the direct basis of this system:

- the memoriale (Italian: memorandum)

- the giornale (Journal)

- the quaderno (ledger)

The ledger classes as the central document and is accompanied by an alphabetical index.[34]

Pacioli's treatise gave instructions on recording barter transactions and transactions in a variety of currencies – both of which were far more common than today. It also enabled merchants to audit their own books and to ensure that the entries in the accounting records made by their bookkeepers complied with the method he described. Without such a system, all merchants who did not maintain their own records were at greater risk of theft by their employees and agents: it is not by accident that the first and last items described in his treatise concern maintenance of an accurate inventory.[35]

The Renaissance cultural context

[edit]Accounting as it developed in Renaissance Europe also had moral and religious connotations, recalling the judgment of souls and the audit of sin.[36]

Financial and management accounting

[edit]The development of joint-stock companies (especially from about 1600) built wider audiences for accounting information, as investors without first-hand knowledge of their operations relied on accounts to provide the requisite information.[37] This development resulted in a split of accounting systems for internal (i.e. management accounting) and external (i.e. financial accounting) purposes, and subsequently also in accounting and disclosure regulations and a growing need for independent attestation of external accounts by auditors.[8]

Modern professional accounting

[edit]Modern Accounting is a product of centuries of thought, custom, habit, action, and convention. Two concepts have formed the current state of the accountancy profession. Firstly, the development of the double-entry book-keeping system in the fourteenth and fifteenth century and secondly, accountancy professionalization which was created in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.[38] The modern profession of the chartered accountant originated in Scotland in the nineteenth century. During this time, accountants often belonged to the same associations as solicitors, and the latter solicitors sometimes offered accounting services to their clients. Early modern accounting had similarities to today's forensic accounting:[39]

- "Like forensic accountants today, accountants then incorporated the duties of expert financial witnesses into their general services rendered. An 1824 circular announcing the accounting practice of one James McClelland of Glasgow promises he will make “statements for laying before arbiters, courts or council.”[39]

In July 1854 the Institute of Accountants in Glasgow petitioned Queen Victoria for a royal charter. The petition, signed by 49 Glasgow accountants, argued that the profession of accountancy had long existed in Scotland as a distinct profession of great respectability, and that although the number of practitioners had been originally few, the number had been rapidly increasing. The petition also pointed out that accountancy required a varied group of skills; as well as mathematical skills for calculation, the accountant had to have an acquaintance with the general principles of the legal system as they were frequently employed by the courts to give evidence on financial matters. The Edinburgh Society of accountants adopted the name "Chartered Accountant" for members.[40]

By the middle of the 19th century, Britain's Industrial Revolution was in full swing, and London was the financial centre of the world. With the growth of the limited liability company and large scale manufacturing and logistics, demand surged for more technically proficient accountants capable of handling the increasingly complex world of high speed global transactions, able to calculate figures like asset depreciation and inventory valuation and cognizant of the latest changes in legislation such as the new Company law, then being introduced. As companies proliferated, the demand for reliable accountancy shot up, and the profession rapidly became an integral part of the business and financial system.

Designations by nationality

[edit]To improve their status and combat criticism of low standards, local professional bodies in England amalgamated to form the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, established by royal charter in 1880.[10] Initially with just under 600 members, the newly formed institute expanded rapidly; it soon drew up standards of conduct and examinations for admission and members were authorised to use the professional designations "FCA" (Fellow Chartered Accountant), for a firm partner and "ACA" (Associate Chartered Accountant) for a qualified member of an accountant's staff.

In the United States the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants was established in 1887.

In Canada, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants was incorporated in 1902,[41][42] the Certified General Accountants Association of Canada was founded in 1908 and the Certified Management Accountants of Canada was incorporated in 1920. These three separate Canadian accounting bodies unified as the Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada (CPA) in 2013.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Keith, Robson. 1992. “Accounting Numbers as ‘inscription’: Action at a Distance and the Development of Accounting.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 17 (7): 685–708.

- ^ a b c d A History of ACCOUNTANCY, New York State Society of CPAs, November 2003, retrieved December 28, 2013

- ^ The History of Accounting, University of South Australia, April 30, 2013, archived from the original on December 28, 2013, retrieved December 28, 2013

- ^ a b کشاورزی, کیخسرو (1980). تاریخ ایران از زمان باستان تا امروز (Translated from Russian by Grantovsky, E.A.) (in Persian). pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Oldroyd, David & Dobie, Alisdair: Themes in the history of bookkeeping, The Routledge Companion to Accounting History, London, July 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-41094-6, Chapter 5, p. 96

- ^ a b Oldroyd, David: The role of accounting in public expenditure and monetary policy in the first century AD Roman Empire, Accounting Historians Journal, Volume 22, Number 2, Birmingham, Alabama, December 1995, p.124, [1]

- ^ a b Heeffer, Albrecht (November 2009). "On the curious historical coincidence of algebra and double-entry bookkeeping" (PDF). Foundations of the Formal Sciences. Ghent University. p. 11.

- ^ a b Lauwers, Luc & Willekens, Marleen: "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1994, vol:XXXIX issue 3, p.302), KUleuven.be

- ^ Timeline of the History of the Accountancy Profession, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, 2013, retrieved December 28, 2013

- ^ a b Perks, R. W. (1993). Accounting and Society. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 16. ISBN 0-412-47330-5.

- ^ a b Friedlob, G. Thomas & Plewa, Franklin James, Understanding balance sheets, John Wiley & Sons, NYC, 1996, ISBN 0-471-13075-3, p.1

- ^ "Discovery of Egyptian Inscriptions Indicates an Earlier Date for Origin of the Alphabet". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Oldroyd, David: The role of accounting in public expenditure and monetary policy in the first century AD Roman Empire, Accounting Historians Journal, Volume 22, Number 2, Birmingham, Alabama, December 1995, p.123, [2]

- ^ Bowman, Alan K., Life and letters on the Roman frontier: Vindolanda and its people Routledge, London, January 1998, ISBN 978-0-415-92024-7, p. 40-41,45

- ^ Farag, Shawki M., The accounting profession in Egypt: Its origin and development, University of Illinois, 2009, p.7 Aucegypt.edu Archived 2010-05-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rathbone, Dominic: Economic Rationalism and Rural Society in Third-Century AD Egypt: The Heroninos Archive and the Appianus Estate, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-03763-8, 1991, p.4

- ^ Cuomo, Serafina: Ancient mathematics, Routledge, London, ISBN 978-0-415-16495-5, July 2001, p.231

- ^ Westland, J. Christopher (2020). Audit Analytics : Data Science for the Accounting Profession. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-49091-1. OCLC 1224141523.

- ^ MEDIEVAL TRADERS AS INTERNATIONAL CHANGE AGENTS: A COMMENT, Michael Scorgie, The Accounting Historians Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1 (June 1994), pp. 137-143

- ^ Westland, J Christopher. (2020). Audit Analytics : Data Science for the Accounting Profession. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-49091-1. OCLC 1224141523.

- ^ Westland, J Christopher. (2020). Audit Analytics : Data Science for the Accounting Profession. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-49091-1. OCLC 1224141523.

- ^ a b c d e Westland, J Christopher. (2020). Audit Analytics : Data Science for the Accounting Profession. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-49091-1. OCLC 1224141523.

- ^ Lee, Geoffrey A., The Coming of Age of Double Entry: The Giovanni Farolfi Ledger of 1299-1300, Accounting Historians Journal, Vol. 4, No. 2, 1977 p.80 University of Mississippi Archived 2017-06-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lauwers, Luc & Willekens, Marleen: "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1994, vol:XXXIX issue 3, p.300), KUleuven.be

- ^ Thiéry, Michel: Did you say Debit?, Assumption University (Thailand), AU-GSB e-Journal, Vol. 2 No. 1, June 2009, p.35, AU.edu Archived 2013-05-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carraro, Carlo; Favero, Giovanni (2016-12-21). Benedetto Cotrugli – The Book of the Art of Trade: With Scholarly Essays from Niall Ferguson, Giovanni Favero, Mario Infelise, Tiziano Zanato and Vera Ribaudo. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-39969-0.

- ^ Hardyment, Richard (2024-04-10). Measuring Good Business: Making Sense of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Data. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-040-00971-0.

- ^ Michael Chatfield; Richard Vangermeersch (2014). The History of Accounting (RLE Accounting): An International Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 183. ISBN 9781134675456.

- ^ Alan Sangster, Greg Stoner & Patricia McCarthy: "The market for Luca Pacioli's Summa Arithmetica" (Accounting, Business & Financial History Conference, Cardiff, September 2007) p.1–2, Cardiff.ac.uk

- ^ "SIESC Croatia 2". www.croatianhistory.net. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ DesignfishStudio. "History of double entry book keeping, origins of book keeping records". www.accountsman.com. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- ^ Carruthers, Bruce G., & Espeland, Wendy Nelson, Accounting for Rationality: Double-Entry Bookkeeping and the Rhetoric of Economic Rationality, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 97, No. 1, July 1991, pp. 37

- ^ Lauwers, Luc & Willekens, Marleen: "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1994, vol:XXXIX issue 3, p.292), KUleuven.be

- ^ Lauwers, Luc & Willekens, Marleen: "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1994, vol:XXXIX issue 3, p.296), KUleuven.be

- ^ Alan Sangster, Using accounting history and Luca Pacioli to teach double entry, Middlesex University Business School, September 2009, p.9, Cardiff.ac.uk

- ^

Soll, Jacob (2014-06-08). "The vanished grandeur of accounting". The Boston Globe. Boston Globe Media Partners, LLC. ISSN 0743-1791. Retrieved 2014-09-30.

Double-entry accounting made it possible to calculate profit and capital and for managers, investors, and authorities to verify books. But at the time, it also had a moral implication. Keeping one's books balanced wasn't simply a matter of law, but an imitation of God, who kept moral accounts of humanity and tallied them in the Books of Life and Death. [...] Accounting was closely tied to the notion of human audits and spiritual reckonings.

- ^ Carruthers, Bruce G., & Espeland, Wendy Nelson, Accounting for Rationality: Double-Entry Bookkeeping and the Rhetoric of Economic Rationality, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 97, No. 1, July 1991, pp. 40-41,44 46,

- ^ Lee, Thomas A (2013-05-01). "Reflections on the origins of modern accounting". Accounting History. 18 (2): 141–161. doi:10.1177/1032373212470548. ISSN 1032-3732. S2CID 155403205.

- ^ a b Donna Bailey Nurse (18 September 2023). "Silent sleuths". AICPA.

- ^ Alexander, John R., "History of Accounting" (ClubExpress, 2002) Ch.12; From "A History of Accounting and Accountants" by Richard Brown, 1905,

- ^ Stephen Bernhut (May 2002). "Setting the standard". CA Magazine. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ SC 1902, c. 58, as amended by SC 1951, c. 89 and SC 1990, c. 52

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Richard, ed. A History of Accounting and Accountants (1905) online old classic

- Chatfield, Michael; Richard Vangermeersch (2014). The History of Accounting: An International Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781134675456.

- Gleeson-White, Jane. Double Entry: How the Merchants of Venice Created Modern Finance (2013)

- King, Thomas A. More Than a Numbers Game: A Brief History of Accounting (2006) excerpt.

- Kirkham, Linda M., and Anne Loft. "The lady and the accounts: missing from accounting history?" Accounting Historians Journal 28.1 (2001): 67–90. online

- Neu, Dean. "“Discovering” indigenous peoples: accounting and the machinery of empire." Accounting Historians Journal 26.1 (1999): 53-82 online; focus on Canada.

- Oldroyd, David. "The role of accounting in public expenditure and monetary policy in the first century AD Roman Empire." Accounting Historians Journal 22.2 (1995): 117–129. online

- Soll, Jacob. The Reckoning: Financial Accountability and the Rise and Fall of Nations (2014), major interpretive history

- Tsuji, Atsuo, and Paul Garner, eds. Studies in Accounting History: Tradition and Innovation for the Twenty-First Century (1995)online

- Wanna, John, Christine Ryan, and Chew Ng, eds. From Accounting to Accountability: A Centenary History of the Australian National Audit Office (2001) online

- Zaid, Omar Abdullah. "Accounting systems and recording procedures in the early Islamic state." Accounting Historians Journal 31.2 (2004): 149–170. online

Great Britain

[edit]- Glynn, John J. "The development of British railway accounting: 1800–1911." Accounting Historians Journal 11.1 (1984): 103–118. online

- Lee, Tom. "The changing form of the corporate annual report." Accounting Historians Journal 21.1 (1994): 215–232. online

- Loft, Anne. "Towards a critical understanding of accounting: the case of cost accounting in the UK, 1914–1925." Accounting, Organizations and Society (1986) 11#2 pp: 137–169.

United States

[edit]- Allen, David Grayson, and Kathleen McDermott. Accounting for Success: A History of Price Waterhouse in America 1890-1990 (Harvard Business School Press, 1993), 373 pp.

- Carey, John L. The rise of the accounting profession: From technician to professional, 1896-1936 (Vol. 1. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 1969)

- Carey, John L. The rise of the accounting profession: To responsibility and authority, 1937-1969 (Vol. 2. American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, 1969)

- Hammond, Theresa A. A White-Collar Profession: African American Certified Public Accountants since 1921 (2002) online

- Miranti, Paul J. Accountancy Comes of Age: The Development of an American Profession, 1886-1940 (1990)

- Pandit, Ganesh M., and C. Richard Baker. "Historical Development of the Standard Audit Report in the US: Form, Scope, and Renewed Attention to Fraud Detection." Accounting Historians Journal 48.1 (2021): 31–45.

- Westland, J Christopher. (2020). Audit Analytics: Data Science for the Accounting Profession. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-49091-1. OCLC 1224141523.

- Zeff, Stephen A. "The evolution of the conceptual framework for business enterprises in the United States." Accounting Historians Journal 26.2 (1999): 89-131 online.

- Zeff, Stephen A. "How the US accounting profession got where it is today: Part II." Accounting Horizons 17#4 (2003): 267–286. online

Historiography

[edit]- Carnegie, Garry D., and Christopher J. Napier. "Popular accounting history: Evidence from post-Enron stories." Accounting Historians Journal 40.2 (2013): 1–19. online

- Fleischman, Richard K., and Vaughan S. Radcliffe. "The roaring nineties: accounting history comes of age." Accounting Historians Journal (2005): 61–109. in JSTOR

External links

[edit] Media related to History of accountancy at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of accountancy at Wikimedia Commons