Publication history of Wonder Woman

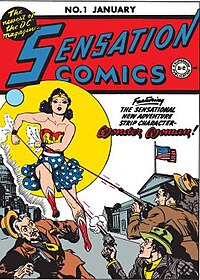

The fictional DC Comics character Wonder Woman was created by William Moulton Marston. She was introduced in All Star Comics #8 (December 1941), then appeared in Sensation Comics #1 (January 1942),[1] Six months later, she appeared in her own comic book series (summer 1942).[2][3] Since her debut, five regular series of Wonder Woman have been published, the fifth launched in June 2016 as part of DC Rebirth.[4]

The Golden Age

[edit]

Wonder Woman was introduced in All Star Comics #8 (December 1941), during the era known to comics historians as the "Golden Age of Comic Books". Following this debut, she was featured in Sensation Comics #1 (January 1942),[1] and six months later appeared in her own comic book series (Summer 1942).[3][2] Wonder Woman took her place beside the extant superheroines or antiheroines Fantomah,[5] the Black Widow, the Invisible Scarlet O'Neil, and Canada's Nelvana of the Northern Lights. Until his death in 1947, Dr. William Moulton Marston was credited with writing all of the Wonder Woman stories; however, later in life, he hired assistant Joye Hummel to ghostwrite stories for him.[6] H. G. Peter penciled the book in a simplistic yet easily identifiable style.

Armed with bulletproof bracelets, a magic lasso, and Amazonian training, Wonder Woman was the archetype of Marston's perfect woman. In Wonder Woman's origin story, Steve Trevor, an intelligence officer in the United States Army, crashed his plane on Paradise Island, the Amazons' isolated homeland. Using a "Purple Ray", Princess Diana nursed him back to health and fell in love with him. When the goddess Aphrodite declared that it was time for an Amazon to travel to "Man's World" and fight the evil of the Nazis, a tournament was held to determine who would be the Amazon champion. Although forbidden by her mother Queen Hippolyte to participate in the tournament, Princess Diana did so nevertheless, her identity hidden by a mask.

After Diana won the tournament and revealed her true identity, Queen Hippolyte relented and allowed her daughter to become Wonder Woman. Diana returned Steve Trevor to the outside world and soon adopted the identity of Army nurse Lt. Diana Prince (by taking the place of her exact double by that name) in order to be close to Trevor as he recovered from his injuries. Afterward, he became Wonder Woman's crimefighting partner and romantic interest.

In her guise as a nurse, Diana cares for Trevor and frequently overhears his intelligence discussions, allowing her to know where she is needed. Prince is eventually hired to work for Trevor in the War Department as his assistant. Trevor periodically suspects that Diana and Wonder Woman might be the same person, especially since he frequently catches Diana using her tiara or lasso.

Wonder Woman was assisted by the Holliday Girls, a sorority from a local women's college led by the sweets-addicted Etta Candy. Etta stood out for several reasons: she had a distinctive figure, she occupied a central role in many storylines, and had an endearing propensity for exclaiming "Woo-woo", which echoed the "Hoo-hoo" catchphrase associated with the popular vaudevillian comedian Hugh Herbert. Etta took her place with Steve Trevor and Diana as the series' most enduring characters.

During 1942 to 1947, images of bound and gagged women frequently graced the covers of Sensation Comics and Wonder Woman. In Wonder Woman #3 (Feb.-March 1943), Wonder Woman herself ties up several women, dresses them in deer costumes and chases them through the forest. Later she rebinds them and displays them on a platter.[7] In addition, Diana is rendered powerless if she allowed a male to chain her bracelets together, although Marston reasoned this as a message to readers warning against allowing men to take away the liberties of women.[3][8] Male characters were also commonly bound, mainly by Wonder Woman herself, although less prominently than women were, and members of both sexes were often dressed in reviling clothing after being captured and enslaved.[9] The comic's sexual subtext has been noted, leading to debates over whether it provided an outlet for Dr. Marston's sexual fantasies or whether it was meant (perhaps unconsciously) to appeal to, and possibly influence, the developing sexuality of young readers.[10]

The bondage and submission elements had a broader context for Marston, who had worked as a prison psychologist. The themes were intertwined with his theories about the rehabilitation of criminals, and from her inception, Wonder Woman wanted to reform the criminals she captured (a rehabilitation complex was created by the Amazons on Transformation Island, a small island near Paradise Island). A core component in Marston's conception of Wonder Woman was "loving submission", in which kindness to others would result in willing submission derived from agape based on Moulton's own personal philosophies.[11]

Alongside the bondage themes in Marston's work, there was a strong feminist presence in Wonder Woman's stories with one titled Battle for Womanhood which saw Diana foiling a plot to discourage the government from allowing women in the workplace.[12] The villain of the piece, Doctor Psycho, was even partially inspired by Marston's anti-feminist and anti-suffrage undergraduate advisor, Hugo Munsterberg.[13] Other stories included a future storyline with a woman US President and a depiction of a lost 'Golden Age' where men shared equal labour, housekeeping and childcare responsibilities with their wives.[14][15]

During this period, Wonder Woman joined the Justice Society of America featured in All Star Comics as its first female member. Reflecting the mores of this pre-feminist era, Wonder Woman served as the group's secretary, despite being one of the group's most powerful members.

Comic strip

[edit]A Wonder Woman newspaper comic strip was produced in 1944, but lasted less than a year.[16] The entire run of the strip was collected in a hardcover book published by The Library of American Comics in 2014.[17] Several of the World War II-era comic book stories featuring Wonder Woman were collected by Chartwell Books in 2015.[18]

Upon William Moulton Marston's death in 1947, the writing duties on Wonder Woman were briefly shared between Hummel and Robert Kanigher, until Hummel shortly quit to care for her step-daughter with her last story being published in 1949 after which Kanigher took over sole writing duties. Diana was written as a less feminist character and began to resemble other traditional American heroines. Notably the comic's 'Wonder Woman of History' centre fold, which depicted the lives of influential and inspirational women, was dropped much to Hummel's objections.[19] Peter produced the art on the title through issue #97, when the elderly artist was fired (he died soon afterward). During this time, Diana's abilities expanded. Her earrings provided her the air she needed to breathe in outer space, and she piloted an "invisible plane", originally a propeller-driven P-40 Warhawk or P-51 Mustang, later upgraded to a jet aircraft. Her tiara was an unbreakable boomerang, and a two-way wrist radio similar to Dick Tracy's was installed in one of her bracelets, allowing her to communicate with Paradise Island.

The Silver Age

[edit]Dr. Fredric Wertham's controversial and influential Seduction of the Innocent (1954) argued that comic books contributed to juvenile delinquency, and alleged that there was a lesbian subtext to the relationship between Wonder Woman and the Holliday Girls. Reacting to Wertham's critique and well-publicized Senate hearings on juvenile delinquency, several publishers organized the Comics Code Authority as a form of preemptive self-censorship. Due to a confluence of forces (amongst them the Code and the loss of Marston as writer), Wonder Woman no longer spoke out as a strong feminist; she began to moon over Steve Trevor, and, as time wore into the Silver Age, also fell for Birdman and Merman.[20]

Prior to the start of the Silver Age of Comic Books in 1956, three superheroes still had their own titles: Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman. Superman was available in "great quantity, but little quality." Batman was doing better, but his comics were "lackluster" in comparison to his "atmospheric adventures" of the 1940s. Wonder Woman, having lost her original writer and artist, was no longer "idiosyncratic" or "interesting".[20]

Wonder Woman experienced significant changes from the late 1950s through the 1960s. Harry G. Peter was replaced by Ross Andru and Mike Esposito with issue #98 (May 1958)[21][22] and the character was revamped, as were other characters in the Silver Age. In Diana's new origin story (issue #105 (December 1958)), it is revealed that her powers are gifts from the gods. Receiving the blessing of each deity in her crib, Diana is destined to become as "beautiful as Aphrodite, wise as Athena, stronger than Hercules, and swifter than Mercury". Further changes included the removal of all World War II references from Wonder Woman's origin, the changing of Hippolyta's hair color to blonde, Wonder Woman's new ability to glide on air currents, and the introduction of the rule that Paradise Island would be destroyed if a man ever set foot on it.

Several years later, when DC Comics introduced the concept of the Multiverse, the Silver Age Wonder Woman was situated as an inhabitant of Earth-One, while the Golden Age Wonder Woman was situated on Earth-Two. It was later revealed, in Wonder Woman #300, that the Earth-Two Wonder Woman had disclosed her secret identity of Diana Prince to the world and had married her Earth's Steve Trevor.

In the 1960s, regular scripter Robert Kanigher adapted several gimmicks which had been used for Superman. As with Superboy, Wonder Woman's "untold" career as the teenage Wonder Girl was chronicled. Then followed Wonder Tot, the infant Amazon princess (in her star-spangled jumper) who experienced improbable adventures with a genie she rescued from an abandoned treasure chest. In a series of "Impossible Tales", Kanigher teamed all three ages of Wonder Woman; her mother, Hippolyta, joined the adventures as "Wonder Queen".

The Diana Prince era and the Bronze Age

[edit]

In 1968, under the guidance of scripter Denny O'Neil and editor/plotter/artist Mike Sekowsky,[23] Wonder Woman voluntarily surrendered her Amazon powers and status to remain in "Man's World" rather than accompany her fellow Amazons to another dimension where they could "restore their magic" (part of her motivation was also to assist Steve Trevor, who was facing criminal charges).

This new era of the comic book was influenced by the British television series The Avengers, with Wonder Woman in the role of Emma Peel.[24] With Diana Prince running a boutique, fighting crime, and acting in concert with private detective allies Tim Trench and Jonny Double, the character resembled the Golden Age version of the Black Canary. Soon after the launch of the "new" Wonder Woman, the editors severed all connections to her old life, most notably by killing off Steve Trevor.[25]

During the 25 bi-monthly issues of the "new" Wonder Woman, the writing team changed four times. Consequently, the stories display abrupt shifts in setting, theme, and tone. The revised series attracted writers not normally associated with comic books, most notably science fiction author Samuel R. Delany, who wrote Wonder Woman #202–203 (October and December 1972).

The I Ching era had an influence on the 1974 Wonder Woman TV movie featuring Cathy Lee Crosby, in which Wonder Woman was portrayed as a non-superpowered globetrotting super-spy who wore an amalgam of the Wonder Woman and Diana Prince costumes. The first two issues of Allan Heinberg's run (Wonder Woman (vol. 3) #1–2) include direct references to I Ching, and feature Diana wearing an outfit similar to that which she wore during the I Ching era.

Wonder Woman's Amazon powers and status and her traditional costume were restored in issue #204 (January–February 1973).[26] Gloria Steinem, who grew up reading Wonder Woman comics, was a key player in the restoration. Steinem, offended that the most famous female superheroine had been de-powered, placed Wonder Woman (in costume) on the cover of the first issue of Ms. (1972) – Warner Communications, DC Comics' owner, was an investor – which also contained an appreciative essay about the character.[27]

The return of the "original" Wonder Woman was executed by Robert Kanigher, who returned as the title's writer-editor. For the first half of the year (Wonder Woman #205-211 (March–April 1973-April–May 1974)) he relied upon rewritten and redrawn stories from the Golden Age adapted for the Bronze Age and set on Earth-One. Following that, a major two-year story arc (largely written by Martin Pasko) consisted of the heroine's attempt to gain re-admission into the Justice League of America (Diana had voluntarily quit the team after renouncing her Amazon powers and status). To prove her worthiness to rejoin the JLA, Wonder Woman voluntarily underwent 12 trials (analogous to the 12 labors of Hercules), each of which was monitored in secret and without her knowledge by a member of the JLA.[28][29]

| Issue (cover date) | Guest star | Writer(s) | Artist(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| #212 (June–July 1974) | Superman II | Len Wein | Curt Swan and Tex Blaisdell |

| #213 (Aug.–Sept. 1974) | the Flash II | Cary Bates | Irv Novick and Tex Blaisdell |

| #214 (Oct.–Nov. 1974) | Green Lantern II | Elliot S. Maggin | Curt Swan and Frank Giacoia (as Phil Zupa) |

| #215 (Dec. 1974-Jan. 1975) | Aquaman II | Cary Bates | John Rosenberger and Vince Colletta |

| #216 (Feb.–March 1975) | the Black Canary II | Elliot S. Maggin | |

| #217 (April–May 1975) | the Green Arrow II | Dick Dillin and Vince Colletta | |

| #218 (June–July 1975) | story #1: the Red Tornado | Martin Pasko | Kurt Schaffenberger |

| story #2: the Phantom Stranger | Martin Pasko and David Michelinie | ||

| #219 (Aug.–Sept. 1975) | the Elongated Man | Martin Pasko | Curt Swan and Vince Colletta |

| #220 (Oct.–Nov. 1975) | the Atom II | Dick Giordano | |

| #221 (Dec. 1975-Jan. 1976) | Hawkman II | Curt Swan and Vince Colletta | |

| #222 (Feb.–March 1976) | the Batman II | José Delbo and Tex Blaisdell |

After the end of this storyline, Wonder Woman underwent her first mission in the JLA after her re-admittance to the team[30] and Steve Trevor was resurrected by Aphrodite due to Hippolyta's displeasure over the 12 trials the JLA had made her daughter go through to be re-admitted to the team in the first place.[31] He adopted the identity of Steve Howard, and worked alongside Diana Prince (he now knew her secret identity as Wonder Woman) at the United Nations.

Soon after this, DC Comics ushered in another format change. Following the popularity of the Wonder Woman TV series (initially set during World War II), the comic book was also transposed to this era.[32] The change was made possible by the DC Multiverse concept, which maintained that the 1970s Wonder Woman and the original 1940s version existed in two separate yet parallel Earths. A few months after the TV series changed its setting to the 1970s, the comic book returned to the contemporary timeline. Soon afterward, when the series was written by Jack C. Harris, Steve (Howard) Trevor was killed off yet again.

Wonder Woman was one of the backup features in World's Finest Comics #244-252 and Adventure Comics #459-464 when those titles were in the Dollar Comics format.[33] All-New Collectors' Edition #C-54 (1978) featured a Superman vs. Wonder Woman story by writer Gerry Conway and artists José Luis García-López and Dan Adkins.[34][35]

The 1980s

[edit]Writer Gerry Conway brought Steve Trevor back to life yet again in issue #271 (September 1980).[36] Following Diana's renunciation of her role as Wonder Woman, a version of Steve Trevor from an undisclosed portion of the Multiverse accidentally made the transition to Earth-One. With Diana's memory erased by the Mists of Nepenthe, the new Steve again crash-landed and arrived at Paradise Island. After reclaiming the title of Wonder Woman, Diana returned to Military Intelligence, working with Trevor and re-joined by supporting characters Etta Candy and General Darnell.

In the preview in DC Comics Presents #41 (January 1982), writer Roy Thomas and penciller Gene Colan provided Wonder Woman with a stylized "WW" emblem on her bodice, replacing the traditional eagle.[37] The "WW" emblem, unlike the eagle, could be protected as a trademark and therefore had greater merchandising potential. Wonder Woman #288 (February 1982) premiered the new costume and an altered cover banner incorporating the "WW" emblem.[38] The new emblem was the creation of Milton Glaser, who also designed the "bullet" logo adopted by DC in 1977, and the cover banner was originally made by studio letterer Todd Klein, which lasted for a year and a half before being replaced by a version from Glaser's studio.[39][40] Dann Thomas co-wrote Wonder Woman #300 (Feb. 1983)[41][42] and, as Roy Thomas noted in 1999 "became the first woman ever to receive scripting credit on the world's foremost super-heroine."[43]

After the departure of Thomas in 1983, Dan Mishkin took over the writing. Mishkin and Colan reintroduced the character Circe to the rogues gallery of Wonder Woman's adversaries.[44] Don Heck replaced Colan as artist as of issue #306 (Aug. 1983), but sales of the title continued to decline.[45] Shortly after Mishkin's departure in 1985 – including a three-issue run by Mindy Newell and a never-published revamp by Steve Gerber[46]– the series ended with issue #329 (February 1986). Written by Gerry Conway, the last issue depicted Wonder Woman's marriage to Steve Trevor.

As a result of the alterations which followed the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover event of 1986, the Wonder Woman and Steve Trevor of Earth-Two, along with all of their exploits, were erased from history. However, the two were admitted into Mount Olympus. At the end of Crisis on Infinite Earths, the Anti-Monitor appeared to have killed the Wonder Woman of Earth-One, but in reality, she had been hurled backwards through time, devolving into the clay from which she had been formed. Crisis on Infinite Earths erased all previously existing incarnations of Wonder Woman from continuity, setting the stage for a complete relaunching and rebooting of the title.[47]

Prior to the publication of Wonder Woman (vol. 2), a four-issue miniseries titled The Legend of Wonder Woman was released with Kurt Busiek as writer and Trina Robbins as artist. The series paid homage to the character's Golden Age roots.[48]

Post-Crisis

[edit]

art by George Pérez

Wonder Woman was rebooted in 1987. Writer Greg Potter, who previously created the Jemm, Son of Saturn series for DC, was hired to rework the character. He spent several months working with editor Janice Race[49] on new concepts, before being joined by writer/artist George Pérez.[50] Inspired by John Byrne and Frank Miller's work on refashioning Superman and Batman, Pérez came in as the plotter and penciler of Wonder Woman.[51] Potter dropped out of writing the series after issue #2,[52][53] and Pérez became the sole plotter. Initially, Len Wein replaced Potter, but Pérez took on the scripting as of issue #18. Mindy Newell would return to the title as scripter with issue #36 (November 1989).[54] Pérez produced 62 issues of the rebooted title. His relaunch of the character was a critical and sales success.[55]

Pérez and Potter wrote Wonder Woman as a feminist character, and Pérez's research into Greek mythology provided Wonder Woman's world with depth and verisimilitude missing from her previous incarnations.[56][57] The incorporation of Greek gods and sharply characterized villains added a richness to Wonder Woman's Amazon heritage and set her apart from other DC superheroes.

Following Pérez, William Messner-Loebs took over as writer and Mike Deodato became the artist for the title. Messner-Loebs introduced Diana's Daxamite friend Julia in Wonder Woman (vol. 2) #68 during the six-issue space story arc.[58][59] Messner-Loebs's most memorable contribution to the title was the introduction of the red-headed Amazon Artemis, who took over the mantle of Wonder Woman for a short time. He also included a subplot during his run in an attempt to further humanize Diana by having her work for a fictional fast food chain called "Taco Whiz".

John Byrne's run included a period in which Diana's mother Hippolyta served as Wonder Woman, having traveled back in time to the 1940s, while Diana ascended to Mount Olympus as the Goddess of Truth after being killed in issue #124.[60] Byrne posited that Hippolyta had been the Golden Age Wonder Woman. Byrne restored the series' status quo in his last issue.[61] In addition, Wonder Woman's Amazon ally Nubia was re-introduced as Nu'Bia, scripted by a different author.

Writer Eric Luke next joined the comic and depicted Diana as often questioning her mission in Man's World, and most primarily her reason for existing. His most memorable contributions to the title was having Diana separate herself from humanity by residing in a floating palace called the Wonder Dome, and for a godly battle between the Titan Cronus and the various religious pantheons of the world. Phil Jimenez worked on the title beginning with issue #164 (January 2001)[62] and produced a run which has been likened to Pérez's, particularly since his art bears a resemblance to Pérez's. Jimenez's run showed Wonder Woman as a diplomat, scientist, and activist who worked to help women across the globe become more self-sufficient. Jimenez also added many visual elements found in the Wonder Woman television series. One of Jimenez's story arcs is "The Witch and the Warrior", in which Circe turns New York City's men into beasts, women against men, and lovers against lovers.[63][64][65]

After Jimenez, Walt Simonson wrote a six-issue homage to the I Ching era, in which Diana temporarily loses her powers and adopts an all-white costume (Wonder Woman (vol. 2) #189–194). Greg Rucka became writer with issue #195. His initial story arc centered upon Diana's authorship of a controversial book and included a political subtext. Rucka introduced a new recurring villain, ruthless businesswoman Veronica Cale, who uses media manipulation to try to discredit Diana. Rucka modernized the Greek and Egyptian gods, updating the toga-wearing deities to provide them with briefcases, laptop computers, designer clothing, and modern hairstyles. Rucka dethroned Zeus and Hades, who were unable to move on with the times as the other gods had, replacing them with Athena and Ares as the new rulers of the gods and the Underworld. Athena selected Diana to be her personal champion.

Infinite Crisis

[edit]The four-part "Sacrifice" storyline, one of the lead-ins to Infinite Crisis, ended with Diana breaking the longstanding do-not-kill code of DC superheroes. Superman, his mind controlled by Maxwell Lord, brutally beats Batman and engages in a vicious fight with Wonder Woman, thinking she is his enemy Doomsday.

art by Phil Jimenez

In the midst of her battle with Superman, Diana realizes that even if she defeats him, he would still remain under Max Lord's absolute mental control. She creates a diversion lasting long enough for her to race back to Max Lord's location and demand that he tell her how to free Superman from his control. Bound by her lasso of truth, Max replies, "Kill me." Wonder Woman then snaps his neck.

Upon his recovery, Batman rejects Diana's attempt to explain her actions; Superman is no better able to understand her motivations. At a crucial time, a profound rift opens up between the three central heroes of the DC universe. In the final pages of The OMAC Project, the Brother Eye satellite – the deranged artificial intelligence controlling the OMACs (Omni Mind And Community) – broadcasts the footage of Wonder Woman dispatching Maxwell Lord to media outlets all over the world, accompanied by the text "Murder."

At the start of Infinite Crisis, Batman and Superman distrust Diana: the latter can only see her as a cold-blooded murderer, the former sees in her an expression of the mentality that led several members of the League to the decision to mindwipe their villains. When Batman tried to stop the League from mindwiping Dr. Light after the villain brutally raped Sue Dibny, Batman's memory was also altered. In Infinite Crisis #2, Brother Eye initiates the final protocol "Truth and Justice", which aims at the total elimination of the Amazons. A full-scale invasion of Themyscira is set into motion utilizing every remaining OMAC. Diana and her countrywomen, now isolated and alienated from the outside world, must fight for their lives.

In Infinite Crisis #3, the Amazons prepare to destroy the OMACs with a powerful new weapon, the Purple Death Ray, a corruption of the healing Purple Ray. Realizing that the battle is being broadcast to TV stations around the world, and edited to make the Amazons look like cold-blooded killers, Wonder Woman convinces the Amazons to shut the weapon down. She then assembles the Amazons on the beach of Themyscira to decide their next move.

Diana calls upon Athena, who transports Paradise Island and the Amazons to another dimension. Wonder Woman chooses not to join them, and is left to face the OMACs on her own. In Infinite Crisis #5, as Diana is breaking up a riot in Boston, she is interrupted by a woman she initially believes is Queen Hippolyta. However, the intruder identifies herself as the Wonder Woman of Earth-Two, Diana Prince, who has voluntarily left Mount Olympus to provide Diana with vital information and guidance. She advises her Post-Crisis counterpart to be "the one thing you haven't been for a very long time... human," and urges Diana to intervene in a fight taking place at that moment between the Modern Age Superman and his counterpart, Kal-L. Having left Mount Olympus, and with her gods' blessings gone, Diana Prince then faded away.

Wonder Woman manages to stop the Supermen from fighting, enabling them to work together in defeating the forces deployed by Alexander Luthor, Jr. and Superboy-Prime, who are revealed as the true culprits behind the Crisis. In the Battle of Metropolis, Diana redeems herself by convincing an anguished Batman not to shoot Luthor, Jr. to death. At the story's conclusion, Diana, Bruce Wayne, and Clark Kent interact like the friends they were in the past, and Diana declares her intention to do some soul-searching before returning to her role as Wonder Woman.

Near the conclusion of the Infinite Crisis, the history of Earth is modified. Wonder Woman's Silver Age past is restored, and it is revealed that she has also served as a founding member of the Justice League. This notion was evidenced in the merging of the Earth-One Wonder Woman and the 1987 rebooted Wonder Woman by Alexander Luthor, Jr.[66]

Wonder Woman (vol. 2) was one of several titles cancelled at the conclusion of the Infinite Crisis crossover event, with #226 (April 2006) being the final issue. The title included 228 published issues (including an issue #0 between issues #90 and 91 and an issue #1,000,000 between issues #138 and 139) and six Annuals.

"One Year Later"

[edit]In conjunction with DC's "One Year Later" crossover storyline, the third Wonder Woman comic series was launched with a new issue #1 (June 2006), written by Allan Heinberg with art by Terry Dodson. Her bustier features a new design, combining the traditional eagle with the 1980s "WW" design, similar to her emblem in the Kingdom Come miniseries.

Wonder Woman asks Kate Spencer, whom she knows to be the Manhunter, to represent her before a Federal grand jury empaneled to determine if she should be tried for the murder of Maxwell Lord; though the World Court has exonerated her, the U.S. government pursues its own charges.[67] Upon concluding their deliberations, the grand jurors refuse to indict Diana.[68]

During the story arc written by Jodi Picoult in issues #6–10, and which ties into Amazons Attack!, Diana is captured and imprisoned by the Department of Metahuman Affairs, led by an impostor Sarge Steel. She is tortured and interrogated to garner information that will allow the United States government to build a Purple Death Ray, previously used during Infinite Crisis.

For reasons of her own, Circe resurrects Diana's mother Hippolyta. When Hippolyta learns that her daughter is being detained by the U.S. government, she goes on the warpath, leading an Amazon assault on Washington, D.C. Freed by Nemesis, Diana tries to reason with her mother to end the war.

In Wonder Woman Annual (vol. 2) #1 (2007), Circe gives Diana the "gift" of human transformation.[69] When she becomes Diana Prince, she transforms into a non-powered mortal. She is content, knowing that she can become Wonder Woman when she wishes and be a member of the human race as Diana Prince.

The relaunch was beset by scheduling problems as described by Grady Hendrix in his article, "Out for Justice" in The New York Sun. "By 2007 [Heinberg had] only delivered four issues ... Ms. Picoult's five issues hemorrhaged readers ... and Amazons Attack!, a miniseries commissioned to fill a hole in the book's publishing schedule caused by Mr. Heinberg's delays, was reviled by fans who decried it as an abomination."[70] Picoult's interpretation received acclaim from critics, who would have liked to have seen the novelist given more time to work. Min Jin Lee of The Times stated, "By furnishing a 21st-century emotional characterization for a 20th-century creation, Picoult reveals the novelist's dextrous hand."[71]

Gail Simone took up writing duties on the title beginning with issue #14.[72]

In the Final Crisis storyline, Diana is attacked by Mary Marvel who infects her with the Morticoccus virus. This seriously deforms Diana and brainwashes her into becoming one of Darkseid's Female Furies. She aids him in conquering Earth, along with other female superheroes/supervillains such as Catwoman, Giganta and Batwoman.

During the Blackest Night event, Diana is lured to Arlington National Cemetery by Maxwell Lord, who is re-animated as a Black Lantern. When Wonder Woman arrives, he springs a trap, using black rings to revive the bodies of fallen soldiers. Wonder Woman uses her Lasso to reduce Lord and the soldiers to dust; as she leaves, the dust begins to regenerate.[73] Later Nekron, Lord of the Dead, the one responsible for the creation of the Black Lantern Corps, reveals that he allowed for Diana's earlier resurrection in order for him to have an "inside agent" among the living. Briefly reanimating Bruce Wayne as a Black Lantern, Nekron creates an emotional tether in Diana, allowing him to place a black power ring on her and transforming her into a Black Lantern.[74] Soon after, a duplicate of Carol Ferris' violet power ring attaches itself to Diana, using her unrequited romantic love for Batman as well as the love she feels for the whole of Earth to destroy the black ring, at the same time turning her into a Star Sapphire. Diana is also given spiritual aid from Aphrodite, the Goddess of Love, in accepting the ring.[75][76] Sometime later, Maxwell Lord attacks Wonder Woman in Coast City. Wonder Woman encases Lord's body in a violet crystal and then shatters it to pieces. She then encounters Mera, who had transformed into a Red Lantern during the fight; their two rings interfaced with each other, Wonder Woman constructs the violet light, giving Mera some measure of control over her new-found savagery.[77] Wonder Woman joins the power of white light and loses her Star Sapphire ring in the final battle.[78]

Wonder Woman was also seen in Justice League of America, encouraging Donna Troy to help create a new Justice League.[79]

Issue #600 and beyond

[edit]DC Comics Executive Editor Dan DiDio asked fans for 600 postcards to restore the Wonder Woman comic book to the original numbering, starting at #600. The publisher's office had received 712 postcards by the October 31, 2009 deadline. As a result, the numbering switched to #600 after Wonder Woman #44 in an anniversary issue.

Writer J. Michael Straczynski took over the title after Gail Simone in issue #601.[80][81][82] The art team was Don Kramer and Michael Babinski.[83]

Straczynski's run focused on an alternate timeline created by the Gods where Paradise Island was destroyed, leading to many Amazons being raised in the outside world. It revolves around Wonder Woman's attempts to restore the normal timeline, despite the fact that she does not remember it properly. Wonder Woman in this alternative timeline has been raised in New York City as an orphan and is only just coming into her powers. She is aware of the presence of Amazons, but does not remember her childhood on Paradise Island.[84][85] Wonder Woman wore a new costume designed by DC Comics co-publisher Jim Lee.[86] Writer Phil Hester continued the storyline.[87]

The decision to redesign Wonder Woman received considerable coverage in mainstream news outlets.[88]

The Wonder Woman in this timeline started off with a limited power set, but gained her magic lasso and the power of flight during the fourth installment of the story.[89]

In addition, the new Wonder Woman costume was used in the intercompany crossover series, JLA/The 99.[90] Despite wearing the new costume, the Wonder Woman in this series is stated to be an Amazon ambassador, indicating that she does not share the same backstory as her counterpart in Straczynski's storyline.[91]

In the Justice League: Generation Lost miniseries, Wonder Woman is shown helping the heroes search for the resurrected Maxwell Lord. Lord uses his psychic powers to the utmost to erase all memory of himself from the minds of the entire world, including Wonder Woman.[92] For some reason, Booster Gold, Captain Atom, Fire and Ice are the only ones who remember Lord's existence. Fire tries talking to Wonder Woman of her killing Lord, but she refuses to believe it and tells Fire that Checkmate has dismissed her for failing her psychological evaluation. Fire discovers that Lord has mentally influenced everyone.[93] Later, in the new timeline, Lord is baffled to discover that all records of Wonder Woman have been erased. Former Justice League members Booster Gold, Captain Atom, Fire and Ice also retain their memories of Wonder Woman but, seemingly, no one else remembers her prior existence.[94] It is later revealed that thanks to the White Lantern, Batman remembers Wonder Woman as he helps Justice League International save her from an attack by Lord's OMACs.[95] Batman learns that since Lord cannot find information on Wonder Woman, he is using JLI to track her down. The OMAC army then teleports Wonder Woman and JLI to Los Angeles. Lord sends the new OMAC known as OMAC Prime, a huge robot, to attack the heroes.[96] JLI saves Wonder Woman from OMAC Prime after nearly being beaten to death.[97]

The New 52

[edit]In August 2011, Wonder Woman (vol. 3) was cancelled, along with every other DC title at the time, as part of a line-wide relaunch following Flashpoint. The series was relaunched in September with a #1 issue written by Brian Azzarello and drawn by Cliff Chiang. Wonder Woman now sports another new costume, once again designed by Jim Lee.[98] Azzarello describes the new Wonder Woman book as being darker than the past series, even going so far as to call it a "horror" book.[99]

In this new continuity, Wonder Woman's origin is significantly changed and she is no longer a clay figure brought to life by the magic of the gods. Instead, she is the natural-born daughter of Hippolyta and Zeus. The earlier origin story was revealed by Hippolyta to be a ruse thought up by the Amazons, to protect Diana from the wrath of Hera, who is known for hunting and killing several illegitimate offspring of Zeus.[100]

In the first story arc, Wonder Woman meets and protects a young woman named Zola from Hera's wrath. Zola is pregnant with Zeus's child and Hera, seething with jealousy, intends to kill the child.[100] [101][102][103] [104][105] The major event in this story is the revelation of Diana's true parentage. Long ago, Hippolyta and Zeus battled each other. Their battle ended with the couple making love and thus Diana was conceived.[100] The first six issues of the New 52 series are collected in a hardcover titled Wonder Woman Vol. 1: Blood.[106]

Wonder Woman also appears as one of the lead characters in the new Justice League title written by Geoff Johns and drawn by Jim Lee[107] Her costume has a slight change. The breastplate she wears in her self-titled series is in the shape of the classic "W" symbol; whereas the breastplate in Justice League resembles a star.

DC Comics revived the Sensation Comics series in August 2014 as a "Digital First" series featuring Wonder Woman.[108] The print edition debuted with an October 2014 cover date.[109] This series was cancelled in December 2015.[110] Artist David Finch and writer Meredith Finch became the new creative team on the Wonder Woman series with issue #36 (Jan. 2015).[111]

DC Rebirth

[edit]As part of the DC Rebirth relaunch, writer Greg Rucka and artists Liam Sharp, Matthew Clark, and Nicola Scott produced a new Wonder Woman series for DC Comics in June 2016.[4][112] The series established that most of the previous run was actually an illusion and effectively reinstated much of the earlier continuity that The New 52 era had overturned, particularly in regards to the background of the Amazons and Themyscira.

Over the Rebirth period Wonder Woman would often defeat her enemies with compassion and love through various means, and at times successfully reform her enemies as she did in the Golden Age era. Wonder Woman's armour also gained a redesign with the lower half of her outfit gaining a short Pteruges like skirt taking influences from her appearance in Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice as well as her armour that she wore when fighting Medusa in Rucka's previous Wonder Woman run. The series also saw the return of Rucka's previous character Veronica Cale as well as the romantic relationship between Diana and Steve Trevor. The plot mainly concerned Cale and Wonder Woman trying to reach the island of Themyscira after Wonder Woman discovered she had in fact been bared from the island. The Rebirth period also saw the Wonder Woman comics issues' numbering order restructured as DC's Doomsday Clock event united the current series to the original Golden Age as one continuous run. This meant the next issue was number #750 despite the previous issue being numbered only #83. To celebrate the event the #750 issue was extra length and collected a variety of short stories celebrating the character of Wonder Woman with previous writers such as Gail Simone and Greg Rucka returning.[113]

New Justice

[edit]Greg Rucka left as author in 2017 and after an intermediate period of various writers.G. Willow Wilson took over in 2018 with a run which saw Wonder Woman finally return to Themyscira.[114] Steve Orlando took over from Wilson in 2020 with Mariko Tamaki taking over from him later in the year.

Infinite Frontier

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (July 2023) |

Dawn of DC

[edit]This article needs to be updated. (July 2023) |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Wallace, Daniel; Dolan, Hannah, ed. (2010). "1940s". DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle. London, United Kingdom: Dorling Kindersley. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-7566-6742-9.

Wonder Woman...took the lead in Sensation Comics following a sneak preview in All Star Comics #8.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Catalog of Copyright Entries 1942 Periodicals Jan-Dec New Series Vol 37 Pt 2. Washington, D.C.: United States Copyright Office. 1942. p. 407.

- ^ a b c "Wonder Woman #1". Grand Comics Database. Summer 1942.

- ^ a b "Wonder Woman #1". DC Comics. June 22, 2016. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016.

- ^ Markstein, Don (2010). "Fantomah, Mystery Woman of the Jungle". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on May 26, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Sexson, WORDS Kathy Leigh Berkowitz PHOTOGRAPHY Amy. "Early Wonder Woman writer lives in Winter Haven". Haven. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (2010). Wonder Woman: Amazon. Hero. Icon. Milan, Italy: Rizzoli Universe Promotional Books. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0789324160.

- ^ Sergi, Joe (October 29, 2012). "Tales From the Code: Whatever Happened to the Amazing Amazon–Wonder Woman Bound by Censorship". Comic Book Legal Defense Fund. Retrieved October 2, 2018.

- ^ Wonder Woman #11 (December 1944)

- ^ Bunn, Geoffrey C. (1997). "The lie detector, Wonder Woman and liberty: the life and work of William Moulton Marston". History of the Human Sciences. 10 (#1). Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications: 91–119. doi:10.1177/095269519701000105. S2CID 143152325.

- ^ Daniels, Les (2000). Wonder Woman: The Complete History. San Francisco, California: Chronicle Books. p. 63. ISBN 0811829138.

William Moulton Marston:

Confinement to WW and the Amazons is just a sporting game, an actual enjoyment of being subdued. This, my dear friend, is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound. Women are exciting for this one reason – it is the secret of women's allure – women enjoy submission, being bound. This I bring out in the Paradise Island sequences where the girls beg for chains and enjoy wearing them.

- ^ Wonder Woman #5 (July 1943)

- ^ Lepore, Jill (2014). "The Last Amazon". The New Yorker.

- ^ Wonder Woman #7 (December 1943)

- ^ Wonder Woman #9 (June 1944)

- ^ Levitz, Paul (2010). 75 Years of DC Comics The Art of Modern Mythmaking. Cologne, Germany: Taschen. p. 168. ISBN 978-3-8365-1981-6.

A "Wonder Woman" newspaper strip was introduced in 1944 but failed to build much of a subscriber list and was canceled within a year.

- ^ Siegel, Lucas (June 24, 2014). "Wonder Woman Strips Collected by IDW August 2014". Newsarama. Archived from the original on October 28, 2015.

DC Entertainment and IDW Publishing are teaming up with the Library of American Comics to bring Wonder Woman: The Complete Newspaper Comics to readers for the first time.

- ^ Johnston, Rich (July 24, 2015). "Roy Thomas Tells The War Years Of Batman, Superman And Wonder Woman". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Harrison (April 8, 2021). "Joye Hummel, first woman hired to write Wonder Woman comics, dies at 97". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Jacobs, Will; Jones, Gerard (1985). The Comic Book Heroes: From the Silver Age to the Present. New York, New York: Crown Publishing Group. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-517-55440-2.

- ^ Irvine, Alex "1950s" in Dolan, p. 90: "Wonder Woman's origin story and character was given a Silver Age revamp, courtesy of writer Robert Kanigher and artist Ross Andru."

- ^ "Wonder Woman #98". Grand Comics Database. May 1958.

- ^ McAvennie, Michael "1960s" in Dolan, p. 131 "Carmine Infantino wanted to rejuvenate what had been perceived as a tired Wonder Woman, so he assigned writer Denny O'Neil and artist Mike Sekowsky to convert the Amazon Princess into a secret agent. Wonder Woman was made over into an Emma Peel type and what followed was arguably the most controversial period in the hero's history."

- ^ Greenberger p. 172: "The staid book suddenly looked new and vibrant, thanks to a new color scheme and mod designs from Sekowsky. He was heavily influenced by then-popular British television series The Avengers."

- ^ O'Neil, Dennis (w), Sekowsky, Mike (p), Giordano, Dick (i). "A Death for Diana!" Wonder Woman, no. 180 (January–February 1969).

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 154 "After nearly five years of Diana Prince's non-powered super-heroics, writer-editor Robert Kanigher and artist Don Heck restored Wonder Woman's...well, wonder."

- ^ Greenberger p. 175: "Journalist and feminist Gloria Steinem...was tapped in 1970 to write the introduction to Wonder Woman, a hardcover collection of older stories. Steinem later went on to edit Ms. Magazine, with the first issue published in 1972, featuring the Amazon Princess on its cover. In both publications, the heroine's powerless condition during the 1970s was pilloried. A feminist backlash began to grow, demanding that Wonder Woman regain the powers and costume that put her on a par with the Man of Steel."

- ^ Jimenez, Phil; Wells, John (2010). The Essential Wonder Woman Encyclopedia. New York, New York: Del Rey Books. pp. 420–421. ISBN 978-0-345-50107-3. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ Pasko, Martin; Wein, Len; Bates, Cary; Maggin, Elliot S.; Michelinie, David (2012). Wonder Woman: The Twelve Labors. New York, New York: DC Comics. p. 232. ISBN 978-1401234942.

- ^ Justice League of America #128-129 (March–April 1976)

- ^ Wonder Woman #223 (April–May 1976)

- ^ McAvennie "1970s" in Dolan, p. 172. "The comic's time and Earth shifts were actually dictated by ABC-TV's popular Wonder Woman TV series, set during World War II, and they continued in this era for the next fifteen issues."

- ^ Romero, Max (July 2012). "I'll Buy That For a Dollar! DC Comics' Dollar Comics". Back Issue! (#57). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 39–41.

- ^ Mangels, Andy (December 2012). "Kryptonian and Amazonian Not Living in Perfect Harmony". Back Issue! (#61). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 50–54.

- ^ "All-New Collectors' Edition #C-54". Grand Comics Database. 1978.

- ^ Manning, Matthew K. "1980s" in Dolan, p.187 "This landmark issue also saw the return of Steve Trevor to Wonder Woman's life in the main feature by writer Gerry Conway and penciller José Delbo."

- ^ Sanderson, Peter (September–October 1981). "Thomas/Colan Premiere Wonder Woman's New Look". Comics Feature (#12/13). New Media Publishing: 23.

The hotly-debated new Wonder Woman uniform will be bestowed on the Amazon Princess in her first adventure written and drawn by her new creative team: Roy Thomas and Gene Colan...This story will appear as an insert in DC Comics Presents #41.

- ^ "Wonder Woman #288". Grand Comics Database. February 1982.

- ^ Keith Dallas, Jason Sacks, Jim Beard, Dave Dykema, Paul Brian McCoy (2013). American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1980s. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 47–8. ISBN 978-1605490465.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Klein, Todd (January 18, 2008). "Logo Study: WONDER WOMAN part 3". Klein Letters. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Dolan, p. 200: "The Amazing Amazon was joined by a host of DC's greatest heroes to celebrate her 300th issue in a seventy-two-page blockbuster...Written by Roy and Dann Thomas, and penciled by Gene Colan, Ross Andru, Jan Duursema, Dick Giordano, Keith Pollard, Keith Giffen, and Rich Buckler."

- ^ Mangels, Andy (December 2013). "Nightmares and Dreamscapes: The Highlights and Horrors of Wonder Woman #300". Back Issue! (#69). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 61–63.

- ^ Thomas, Roy (Summer 1999). "The Secret Origins of Infinity, Inc". Alter Ego. 3 (#1). Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing: 27.

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Dolan, p. 202: "The sorceress Circe stepped out of the pages of Homer's Odyssey and into the modern mythology of the DC Universe in Wonder Woman #305, courtesy of Dan Mishkin's script and Gene Colan's pencils."

- ^ Coates, John (2014). Don Heck: A Work of Art. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-1605490588.

The circulation numbers reported in #325 show a -46% decrease over the previous 24 issues, back to #303.

- ^ Cronin, Brian (April 1, 2010). "Comic Book Legends Revealed #254". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

Gerber and Frank Miller pitched DC on revamps of the "Trinity." The three titles would be called by the "line name" of METROPOLIS, with each character being defined by one word/phrase… AMAZON (written by Gerber); DARK KNIGHT (written by Miller); and Something for Superman – I believe either MAN OF STEEL or THE MAN OF STEEL, but I'm not sure about that (written by both men).

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Dolan, p. 227 "Wonder Woman received a complete and utter makeover, even more so than the Man of Steel and the Dark Knight. Her adventures started from scratch, and unlike Superman and Batman's revamped origins, occurred in the present, rather than in flashback fashion."

- ^ "Q & A with Trina Robbins – first woman to draw Wonder Woman comics". The Vancouver Sun. Vancouver, BC, Canada. November 5, 2014. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015.

- ^ Gold, Alan "Wonder Words" letter column, Wonder Woman #329 (February 1986) "[Alan Gold will] be turning over the editorial reins to Janice Race...She has been working for several months already, as a matter of fact, with a bright new writer named Greg Potter."

- ^ "Newsflashes". Amazing Heroes (#82). Fantagraphics Books: 8. November 1, 1985.

Pérez's Amazon: George Pérez will be co-plotting and penciling the new Wonder Woman series, scheduled to debut in June 1986 [sic]. Greg Potter will be the writer and co-plotter with Pérez

- ^ Pérez, George, "The Wonder Of It All", text article in Wonder Woman (vol. 2) #1 (February 1987)

It was the fall of 1985...I walked into editor Janice Race's office to find out about the fate of Diana Prince. I was curious to learn who was going to draw her. Superman had [John] Byrne and [Jerry] Ordway, Batman had [Frank] Miller and [Alan] Davis (and later [David] Mazzucchelli). Wonder Woman had...No one. A writer, Greg Potter, had been selected but no established artist wanted to handle the new series. After exhaustive searches, it seemed Wonder Woman would have to be assigned to an unknown...I thought of John Byrne and Superman. What a giant coup for DC. A top talent and fan-fave on their premier character..."Janice" I heard myself say "What if I took on Wonder Woman for the first six months - just to get her out of the starting gate?"

- ^ Berger, Karen letter column, Wonder Woman #5 (June 1987) "Greg is also the creative director of a Connecticut-based advertising agency. Greg chose to further his career in the aforementioned area, and very reluctantly had to relinquish the scripting after helping to launch our series."

- ^ Nolen-Weathington, Eric (2003). Modern Masters Volume 2: George Pérez. Raleigh, North Carolina: TwoMorrows Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 1-893905-25-X. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

But with the changes I [George Pérez] was making, I think Greg decided that maybe it wasn't for him and he bowed out after issue #2.

- ^ Mindy Newell's Wonder Woman credits at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Mangels, Andy (January 1, 1989). "Triple Threat The George Pérez Interview". Amazing Heroes (#156). Fantagraphics Books: 30.

Wonder Woman's sales are some of the best the Amazing Amazon has ever experienced, and the book is a critical and popular success with its weaving of Greek mythology into a feminist and humanistic atmosphere.

- ^ Manning "1980s" in Dolan, p. 227 "With the help of Pérez's meticulous pencils, as well as his guidance as co-plotter, Wonder Woman was thrust further into the realm of Greek mythology than she'd ever been before."

- ^ Daniels, Les (1995). "The Amazon Redeemed Wonder Woman Returns to Her Roots". DC Comics: Sixty Years of the World's Favorite Comic Book Heroes. New York, New York: Bulfinch Press. p. 194. ISBN 0821220764.

Creator William Moulton Marston had mixed Roman gods in with the Greek, but Pérez kept things straight even when it involved using a less familiar name like 'Ares' instead of 'Mars'. The new version also jettisoned the weird technology anachronistically present on the original Paradise Island.

- ^ Messner-Loebs, William (w), Cullins, Paris (p), McLaughlin, Frank (i). "Breaking Bonds" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 68 (November 1992).

- ^ Messner-Loebs, William (w), Cullins, Paris (p), Tanghal, Romeo (i). "Home Again" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 71 (February 1993).

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Dolan, p. 280 "It seemed Wonder Woman had breathed her last in Wonder Woman #124, thanks to writer and artist John Byrne."

- ^ Manning "1990s" in Dolan, p. 284 "Writer/artist John Byrne was leaving Wonder Woman...But before he could move on to other projects, there was one final thing Byrne still had to do: bring Wonder Woman back from the dead."

- ^ Cowsill, Alan "2000s" in Dolan, p. 298 "The 'Gods of Gotham' storyline marked the start of Phil Jimenez's run on the series as artist and writer (with J. M. DeMatteis on board as co-scripter for the first arc)."

- ^ Jimenez, Phil (w), Jimenez, Phil (p), Lanning, Andy; Stucker, Lary; Alquiza, Marlo (i). "The Witch and the Warrior Part One" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 174 (November 2001).

- ^ Jimenez, Phil (w), Jimenez, Phil; Badeaux, Brandon (p), Lanning, Andy; Stucker, Lary; Marzan Jr., José; Conrad, Kevin; Alquiza, Marlo (i). "The Witch and the Warrior Part Two: Girl Frenzy" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 175 (December 2001).

- ^ Jimenez, Phil (w), Jimenez, Phil (p), Lanning, Andy (i). "The Witch and the Warrior Part Three: Hateful Hate" Wonder Woman, vol. 2, no. 176 (January 2002).

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Jimenez, Phil (p), Lanning, Andy (i). "Touchdown" Infinite Crisis, no. 6 (May 2006).

- ^ Andreyko, Marc (w), Pina, Javier (p), Riggs, Robin (i). "Unleashed Part One: The Lady in Question" Manhunter, vol. 4, no. 26 (February 2007).

- ^ Andreyko, Marc (w), Pina, Javier; Olmos, Diego; Cafu (p), Riggs, Robin; Thibert, Art (i). "Unleashed Conclusion: Hail and Farewell" Manhunter, vol. 4, no. 30 (June 2007).

- ^ Heinberg, Allan (w), Dodson, Terry (p), Dodson, Rachel (i). "Who Is Wonder Woman? Part Five" Wonder Woman Annual, vol. 2, no. 1 (November 2007).

- ^ Hendrix, Grady (December 11, 2007). "Out for Justice". The New York Sun. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Lee, Min Jin (January 18, 2008). "Wonder Woman: Love and Murder by Jodi Picoult". The Times. Archived from the original on July 6, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Simone, Gail (w), Dodson, Terry (p), Dodson, Rachel (i). "The Circle, Part One of Four: What You Do Not Yet Know" Wonder Woman, vol. 3, no. 14 (January 2008).

- ^ Rucka, Greg (w), Scott, Nicola (p), Rollins, Prentis; Glapion, Jonathan; Wong, Walden; Geraci, Drew (i). "Part One: The Living" Blackest Night: Wonder Woman, no. 1 (February 2010).

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Reis, Ivan (p), Albert, Oclair; Prado, Joe (i). "What is Nekron?" Blackest Night, no. 5 (January 2010).

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Reis, Ivan (p), Albert, Oclair; Prado, Joe (i). "Die!" Blackest Night, no. 6 (February 2010).

- ^ Rucka, Greg (w), Scott, Nicola; Pansica, Eduardo (p), Glapion, Jonathan; Ferreira, Eber (i). Blackest Night: Wonder Woman, no. 2 (March 2010).

- ^ Rucka, Greg (w), Scott, Nicola (p), Glapion, Jonathan (i). "Blackest Night" Blackest Night: Wonder Woman, no. 3 (April 2010).

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Reis, Ivan (p), Albert, Oclair; Prado, Joe (i). Blackest Night, no. 8 (May 2010).

- ^ Robinson, James (w), Bagley, Mark (p), Hunter, Rob; Alquiza, Marlo; Wong, Walden (i). "Team History" Justice League of America, vol. 2, no. 41 (March 2010).

- ^ "J. Michael Straczynski to write Superman and Wonder Woman, starting in July". DC Comics. March 8, 2010. Archived from the original on April 22, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Phegley, Kiel (March 8, 2010). "Straczynski Steps Up For Superman & Wonder Woman". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ "Straczynski Talks Superman & Wonder Woman". Newsarama. March 8, 2010. Archived from the original on September 25, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ "Who destroyed Paradise Island?". DC Comics. April 15, 2010. Archived from the original on September 22, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Rogers, Vaneta (June 29, 2010). "JMS Talks Wonder Woman's New Look and New Direction". Newsarama. Archived from the original on February 1, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ George, Richard (July 7, 2010). "Wonder Woman's New Era". IGN. Archived from the original on June 15, 2011. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Gustines, George Gene (June 29, 2010). "Makeover for Wonder Woman at 69". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2022. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Ching, Albert (November 10, 2010). "JMS Leaving Superman and Wonder Woman for Earth One Sequel". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 30, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ "Fans react to Wonder Woman's costume change". CNN. July 1, 2010. Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Straczynski, J. Michael (w), Kramer, Don; Pansica, Eduardo (p), Leisten, Jay (i). "Odyssey Part Four" Wonder Woman, no. 604 (December 2010).

- ^ Justice League of America / The 99 at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Moore, Stuart; Nicieza, Fabian (w), Derenick, Tom (p), Drew Geraci, Drew (i). "The City of Tomorrow" Justice League of America / The 99, no. 1 (December 2010).

- ^ Winick, Judd; Giffen, Keith (w), Giffen, Keith; Lopresti, Aaron (p), Ryan, Matt (i). "Part One: Gone But Not Forgotten" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 1 (early July 2010).

- ^ Winick, Judd (w), Giffen, Keith; Bennett, Joe (p), Jadson, Jack (i). "Part Two: Max'ed Out" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 2 (late July 2010).

- ^ Winick, Judd (w), Bennett, Joe (p), Jadson, Jack; José, Ruy (i). "Tomorrow is Today" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 15 (early February 2011).

- ^ Winick, Judd (w), Bennett, Joe (p), Jadson, Jack; José, Ruy (i). "Part Twenty-Two: A Good News, Bad News Sort of Thing" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 22 (late May 2011).

- ^ Winick, Judd (w), Dagnino, Fernando (p), Fernandez, Raul (i). "Caught" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 23 (early June 2011).

- ^ Winick, Judd (w), Lopresti, Aaron (p), Ryan, Matt (i). "It All Comes Down to This!" Justice League: Generation Lost, no. 24 (late June 2011).

- ^ Thill, Scott (August 31, 2011). "Rebooted Justice League Offers Peek at DC Comics' 'New World Order'". Wired. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Melrose, Kevin (August 22, 2011). "Relaunched Wonder Woman is 'a horror book,' Brian Azzarello says". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ a b c Azzarello, Brian (w), Chiang, Cliff (p), Chiang, Cliff (i). "Clay" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 3 (January 2012).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian (w), Chiang, Cliff (p), Chiang, Cliff (i). "The Visitation" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 1 (November 2011).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian (w), Chiang, Cliff (p), Chiang, Cliff (i). "Home" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 2 (December 2011).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian (w), Chiang, Cliff (p), Chiang, Cliff (i). "Blood" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 4 (February 2012).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian (w), Akins, Tony (p), Akins, Tony (i). "Lourdes" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 5 (March 2012).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian (w), Akins, Tony (p), Akins, Tony; Green, Dan (i). "Thrones" Wonder Woman, vol. 4, no. 6 (April 2012).

- ^ Azzarello, Brian; Chiang, Cliff (2012). Wonder Woman Vol. 1: Blood. New York, New York: DC Comics. p. 160. ISBN 978-1401235635.

- ^ Johns, Geoff (w), Lee, Jim (p), Williams, Scott (i). "Justice League Part Three" Justice League, vol. 2, no. 3 (January 2012).

- ^ Yehl, Joshua (May 19, 2014). "DC Comics to Publish Digital First Sensation Comics Featuring Wonder Woman". IGN. Archived from the original on August 3, 2014.

- ^ Sensation Comics Featuring Wonder Woman at the Grand Comics Database

- ^ Arrant, Chris (September 14, 2015). "Updated: Batman '66 and Sensation Comics Also Ending, GL: Lost Army A Miniseries". Newsarama. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015.

In the DC December 2015 solicitations, both Batman '66 and Sensation Comics Featuring Wonder Woman are listed as ending with that month's issues.

- ^ Campbell, Josie (July 1, 2014). "Meredith, David Finch Discuss Taking Wonder Woman More 'Mainstream'". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014.

Azzarello and Chiang hand over the keys to the Amazonian demigod's world to the just-announced husband-and-wife team of artist David Finch and writer Meredith Finch.

Archive requires scrolldown - ^ Phegley, Kiel (May 23, 2016). "Rucka, Sharp & Scott Aim To Make Rebirth's Wonder Woman Accessible & Fantastic". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016.

While Wonder Woman sees the return of writer Greg Rucka, he's teaming up with Liam Sharp, Matthew Clark and Nicola Scott to deliver a very different take from his previous run with the Amazon Princess.

Archive requires scrolldown. - ^ "WONDER WOMAN #750". DC. April 17, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "G. Willow Wilson Announced as New Wonder Woman Writer". July 11, 2018. Archived from the original on July 13, 2018. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

External links

[edit]- Wonder Woman at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Wonder Woman vol. 2 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Wonder Woman vol. 3 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Wonder Woman vol. 4 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

- Wonder Woman sales history at Comichron