Historical reliability of the Gospels

| Part of a series on |

|

The historical reliability of the Gospels is evaluated by experts who have not reached complete consensus. While all four canonical gospels contain some sayings and events that may meet at least one of the five criteria for historical reliability used in biblical studies,[note 1] the assessment and evaluation of these elements is a matter of ongoing debate.[1][note 2]

Virtually all scholars of antiquity agree that Jesus of Nazareth existed in 1st-century Judaea in the Southern Levant[2][3][4] but scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the biblical accounts of him.[5] The only two events subject to "almost universal assent"[6] are that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist and that he was crucified by order of the Roman Prefect Pontius Pilate.[7] There is no scholarly consensus about other elements of Jesus's life, including the two accounts of the Nativity of Jesus, the miraculous events such as the resurrection, and certain details of the crucifixion.[8][9]

According to the majority viewpoint, the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, collectively called the Synoptic Gospels, are the primary sources of historical information about Jesus[10] and the religious movement he founded.[11] The fourth gospel, John, differs greatly from the other three.[note 3] A growing majority of scholars consider the Gospels to be in the genre of Ancient Greco-Roman biographies,[12] the same genre as Plutarch's Life of Alexander and Life of Caesar. Typically, ancient biographies written shortly after the death of the subject and include substantial history.[13]

Historians analyze the Gospels critically, attempting to differentiate reliable information from possible inventions, exaggerations, and alterations.[14] Scholars use textual criticism to resolve questions arising from textual variations among the numerous extant manuscripts to decide the wording of a text closest to the "original".[15] Scholars seek to answer questions of authorship and date and purpose of composition, and they look at internal and external sources to determine the gospel traditions' reliability.[16] Historical reliability does not depend on a source's inerrancy or lack of agenda since some sources (e.g. Josephus) are considered generally reliable despite having such traits.[17]

Methodology

[edit]In evaluating the Gospels' historical reliability, scholars consider authorship and date of composition,[18] intention and genre,[16] gospel sources and oral tradition,[19][20] textual criticism,[21] and the historical authenticity of sayings and narrative events.[18]

Scope and genre

[edit]"Gospels" is the standard term for the four New Testament books carrying the names of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, each recounting the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (including his dealings with John the Baptist, his trial and execution, the discovery of his empty tomb, and, at least in three of them, his appearances to his disciples after his death).[22]

The genre of the gospels is essential in understanding the authors' intentions regarding the texts' historical value. New Testament scholar Graham Stanton writes, "the gospels are now widely considered to be a sub-set of the broad ancient literary genre of biographies."[23] Charles H. Talbert agrees that the gospels should be grouped with the Graeco-Roman biographies, but adds that such biographies included an element of mythology, and that the synoptic gospels do too.[24] E. P. Sanders writes, "these Gospels were written with the intention of glorifying Jesus and are not strictly biographical in nature."[14] M. David Litwa argues that the gospels belonged to the genre of "mythic historiography", where miracles and other fantastical elements were narrated in less sensationalist ways and the events were considered to have actually occurred by the readers of the time.[25] Craig S. Keener argues that the gospels are ancient biographies whose authors, like other ancient biographers at the time, were concerned with describing accurately the life and ministry of Jesus.[26] Ingrid Maisch and Anton Vögtle, writing for Karl Rahner in his encyclopedia of theological terms, say that the gospels were written primarily as theological, not historical, texts.[27] Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis writes, "we must conclude, then, that the genre of the Gospel is not that of pure 'history'; but neither is it that of myth, fairy tale, or legend. In fact, 'gospel' constitutes a genre all its own, a surprising novelty in the literature of the ancient world."[28]

Scholars tend to consider Luke's works (Luke-Acts) closer in genre to pure history,[29][30] but they also note that "This is not to say that he [Luke] was always reliably informed, or that – any more than modern historians – he always presented a severely factual account of events."[29] Regardless EP Sanders claimed that the sources for Jesus are superior to the ones for Alexander the Great.[31]

New Testament scholar James D.G. Dunn believed that "the earliest tradents within the Christian churches [were] preservers more than innovators...seeking to transmit, retell, explain, interpret, elaborate, but not create de novo...Through the main body of the Synoptic tradition, I believe, we have in most cases direct access to the teaching and ministry of Jesus as it was remembered from the beginning of the transmission process (which often predates Easter) and so fairly direct access to the ministry and teaching of Jesus through the eyes and ears of those who went about with him."[32] Anthony Le Donne, a leading memory researcher in Jesus studies, elaborated on Dunn's thesis, basing "his historiography squarely on Dunn’s thesis that the historical Jesus is the memory of Jesus recalled by the earliest disciples."[33] According to Le Donne as explained by his reviewer, Benjamin Simpson, memories are fractured, and not exact recalls of the past. Le Donne further argues that the remembrance of events is facilitated by relating it to a common story, or "type." This means the Jesus-tradition is not a theological invention of the early Church, but rather a tradition shaped and refracted through such memory "type." Le Donne too supports a conservative view on typology compared to some other scholars, transmissions involving eyewitnesses, and ultimately a stable tradition resulting in little invention in the Gospels.[33] Le Donne expressed himself thusly vis-a-vis more skeptical scholars, "He (Dale Allison) does not read the gospels as fiction, but even if these early stories derive from memory, memory can be frail and often misleading. While I do not share Allison's point of departure (i.e. I am more optimistic), I am compelled by the method that came from it."[34]

Dale Allison emphasizes the weakness of human memory, referring to its 'many sins' and how it frequently misguides people. He expresses skepticism at other scholars' endeavors to identify authentic sayings of Jesus. Instead of isolating and authenticating individual pericopae, Allison advocates for a methodology focused on identifying patterns and finding what he calls 'recurrent attestation'. Allison argues that the general impressions left by the Gospels should be trusted, though he is more skeptical on the details; if they are broadly unreliable, then our sources almost certainly cannot have preserved any of the particulars. Opposing preceding approaches where the Gospels are historically questionable and must be rigorously sifted through by competent scholars for nuggets of information, Allison argues that the Gospels are generally accurate and often 'got Jesus right'. Dale Allison finds apocalypticism to be recurrently attested, among various other themes. [35] Reviewing his work, Rafael Rodriguez largely agrees with Allison's methodology and conclusions while arguing that Allison's discussion on memory is too one-sided, noting that memory "is nevertheless sufficiently stable to authentically bring the past to bear on the present" and that people are beholden to memory's successes in everyday life. [36]

According to Bruce Chilton and Craig Evans, "...the Judaism of the period treated such traditions very carefully, and the New Testament writers in numerous passages applied to apostolic traditions the same technical terminology found elsewhere in Judaism [...] In this way they both identified their traditions as 'holy word' and showed their concern for a careful and ordered transmission of it."[37]David Jenkins, a former Anglican Bishop of Durham and university professor, has said: "Certainly not! There is absolutely no certainty in the New Testament about anything of importance."[38]

Chris Keith has called for the employment of social memory theory regarding the memories transmitted by the Gospels over the traditional form-critical approach emphasizing a distinction between 'authentic' and 'inauthentic' tradition. Keith observes that the memories presented by the Gospels can contradict and are not always historically correct. Chris Keith argues that the Historical Jesus was the one who could create these memories, both true or not. For instance, Mark and Luke disagree on how Jesus came back to the synagogue, with the likely more accurate Mark arguing he was rejected for being an artisan, while Luke portrays Jesus as literate and his refusal to heal in Nazareth as cause of his dismissal. Keith does not view Luke's account as a fabrication since different eyewitnesses would have perceived and remembered differently. [39]

While believing that the study of the process of conversion from memories of Jesus into the Gospel tradition are too complicated for more simplistic a priori arguments the Gospels are reliable,[40] Alan Kirk, notable for introducing the methodology of social memory theory to New Testament scholarship along with Tom Thatcher,[41] criticizes allegations of memory distortion common in Biblical studies. Kirk finds that much research in psychology involves experimentation in labs decontextualized from the real world, making use of their results dubious, hence the rise of what he calls 'ecological' approaches to memory. Kirk claims that social contagion is one phenomenon that is greatly lessened or even ruled out by new study. Kirk claims that there is also an imprudent reliance on a binary distinction between exact information and later interpretation in research.[42] Kirk argues that the demise of form criticism means that the Gospels can no longer be automatically considered unreliable and that skeptics must now find new options, such as the aforementioned efforts at using evidence of memory distortion.[43] Reviewing Kirk's essay "Cognition, Commemoration, and Tradition: Memory and the Historiography of Jesus Research" (2010), biblical scholar Judith Redman provides a reflection based on her view of memory research:

They [The Gospels] are not ordinary historical accounts and cannot be treated as though they are, but nor are they simply ahistorical materials designed to convince the reader of the author's particular theological perspective. That we have increasing scientific evidence of this has important implications for Christians, but does not, I think, invalidate the preceding two millennia of faith.[44]

Alongside his work defining the Gospels as ancient biography, Craig Keener, drawing on the works of previous studies by Dunn, Kirk, Kenneth Bailey, and Robert McIver, among many others, utilizes memory theory and oral tradition to argue that the Gospels are in many ways historically accurate.[45] His work has been endorsed by Richard Bauckham, Markus Bockmuehl, and David Aune, among others.[45]

Criteria

[edit]Critical scholars have developed a number of criteria to evaluate the probability or historical authenticity of an attested event or saying in the gospels. These criteria are the criterion of dissimilarity; the criterion of embarrassment; the criterion of multiple attestation; the criterion of cultural and historical congruency; and the criterion of "Aramaisms". They are applied to the sayings and events described in the Gospels to evaluate their historical reliability.

The criterion of dissimilarity argues that if a saying or action is dissimilar or contrary to the views of Judaism in the context of Jesus or the views of the early church, then it can more confidently be regarded as an authentic saying or action of Jesus.[46][47] Commonly cited examples of this are Jesus's controversial reinterpretation of Mosaic law in his Sermon on the Mount and Peter's decision to allow uncircumcised gentiles into what was at the time a sect of Judaism.

The criterion of embarrassment holds that the authors of the gospels had no reason to invent embarrassing incidents such as Peter's denial of Jesus or the fleeing of Jesus's followers after his arrest, and therefore such details would likely not have been included unless they were true.[48] Bart Ehrman, using the criterion of dissimilarity to judge the historical reliability of the claim that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist, writes, "it is hard to imagine a Christian inventing the story of Jesus' baptism since this could be taken to mean that he was John's subordinate."[49]

The criterion of multiple attestation says that when two or more independent sources present similar or consistent accounts, it is more likely that the accounts are accurate reports of events or that they are reporting a tradition that predates the sources.[50] Since Matthew and Luke borrow a lot of material from Mark, agreement among the synoptic gospels is not evidence of independent sources, but often they recount the same events as John, and Paul's epistles also attest to some of these events. The writings of the early church provide additional evidence, as to a limited degree do non-Christian ancient writings.

The criterion of cultural and historical congruency says that a source is less credible if the account contradicts known historical facts, or if it conflicts with cultural practices common in the period in question.[51] It is, therefore, more credible if it agrees with those known facts. For example, this is often used when assessing the reliability of claims in Luke-Acts, such as the official title of Pontius Pilate. Through linguistic criteria a number of conclusions can be drawn.

The criterion of "Aramaisms"[52] is that if a saying of Jesus has Aramaic roots, reflecting his Palestinian cultural context, it is more likely to be authentic than a saying that lacks Aramaic roots.[53]

Formation and sources

[edit]

From oral traditions to written gospels

[edit]Most scholars believe that the Historical Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet who predicted the imminent end or transformation of the world, though others, notably the Jesus Seminar, disagree.[54] As eyewitnesses began to die, and as the missionary needs of the church grew, there was an increasing demand and need for written versions of the founder's life and teachings.[55] The stages of this process can be summarised as follows:[56]

- Oral traditions – stories and sayings passed on largely as separate self-contained units, not in any order;

- Written collections of miracle stories, parables, sayings, etc., with oral tradition continuing alongside these;

- Written proto-gospels preceding and serving as sources for the gospels;

- Canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John composed from these sources.

The New Testament preserves signs of these oral traditions and early documents:[57] for example, parallel passages between Matthew, Mark and Luke on one hand and the Pauline epistles and the Epistle to the Hebrews on the other are typically explained by assuming that all were relying on a shared oral tradition,[citation needed] and the dedicatory preface of Luke refers to previous written accounts of the life of Jesus.[58] The early traditions were fluid and subject to alteration, sometimes transmitted by those who had known Jesus personally, but more often by wandering prophets and teachers like the Apostle Paul, who did not know him personally.[59] Jens Schroter argued that a mass of material from various sources, such as Christian prophets issuing sayings in the name of Jesus, the Hebrew Bible, miscellaneous sayings, alongside the actual words of Jesus, were all attributed by the Gospels to the singular historical Jesus.[60] However, James DG Dunn and Tucker Ferda point out that the early Christian tradition sought to distinguish between their own sayings and those of the historical Jesus and that there is little evidence that the claims of new "prophets" often became mistaken as those of Jesus himself; Ferda notes that the phenomena of prophetic sayings merging with those of Jesus is more relevant to the dialogue gospels of the second and third centuries.[61][62] The accuracy of the oral gospel tradition was insured by the community designating certain learned individuals to bear the main responsibility for retaining the gospel message of Jesus. The prominence of teachers in the earliest communities such as the Jerusalem Church is best explained by the communities' reliance on them as repositories of oral tradition.[63] The early prophets and leaders of local Christian communities and their followers were more focused on the Kingdom of God than on the life of Jesus: Paul for example, says very little about him such as he was "born of a woman" (meaning that he was a man and not a phantom), that he was a Jew, and that he suffered, died, and was resurrected: what mattered for Paul was not Jesus's teachings or the details of his death and resurrection, but the kingdom.[64] Nonetheless, Paul was personally acquainted with Peter and John, two of Jesus’ original disciples, and James, the brother of Jesus.[65][66] Paul's first meeting with Peter and James was approximately 36 AD, close to the time of the crucifixion (30 or 33 AD.)[66] Paul was a contemporary of Jesus and, according to some, from Paul's writings alone, a fairly full outline of the life of Jesus can found: his descent from Abraham and David, his upbringing in the Jewish Law, gathering together disciples, including Cephas (Peter) and John, having a brother named James, living an exemplary life, the Last Supper and betrayal, numerous details surrounding his death and resurrection (e.g. crucifixion, Jewish involvement in putting him to death, burial, resurrection, seen by Peter, James, the twelve and others) along with numerous quotations referring to notable teachings and events found in the Gospels.[67][68]

The four canonical gospels were first mentioned[citation needed] between 120 and 150 by Justin Martyr, who lived in 2nd century Flavia Neapolis (Biblical Shechem, modern day Nablus) .Justin had no titles for them and simply called them the "memoirs of the Apostles". Around 185 Iraneus, a bishop of Lyon who lived c.130–c.202, attributed them to: 1) Matthew, an apostle who followed Jesus in his earthly career; 2) Mark, who while himself not a disciple was the companion of Peter, who was; 3) Luke, the companion of Paul, the author of the Pauline epistles; and 4) John, who like Matthew was an apostle who had known Jesus.[citation needed] Most scholars agree that they are the work of unknown Christians[69] and were composed c.65-110 AD.[70] The majority of New Testament scholars also agree that the Gospels do not contain direct eyewitness accounts,[71] but that they present the theologies of their communities rather than the testimony of eyewitnesses.[72][73] Nevertheless, they preserve sources that go back to Jesus and his contemporaries,[74][75][76] and the Synoptic writers thought that they were reconfiguring memories of Jesus rather than creating theological stories,[77][note 4], "draw[ing] on direct memories of the first generation of Jesus' disciples."[78]

The synoptics: Matthew, Mark and Luke

[edit]

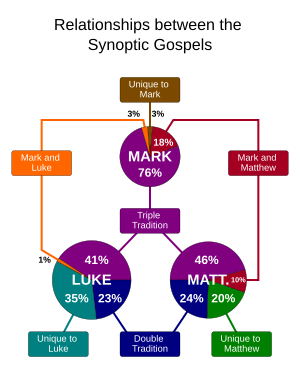

Matthew, Mark and Luke are called the synoptic gospels because they share many stories (the technical term is pericopes), sometimes even identical wording; finding an explanation for their similarities, and also their differences, is known as the synoptic problem,[79] and most scholars believe that the best solution to the problem is that Mark was the first gospel to be written and served as the source for the other two[80] - alternative theories exist, but create more problems than they solve.[81] Since the third quest for the historical Jesus, the four gospels and noncanonical texts have been viewed with more confidence as sources to reconstruct the life of Jesus compared to the previous quests.[82]

Matthew and Luke also share a large amount of material which is not found in Mark; this appears in the same order in each, although not always in the same contexts, leading scholars to the conclusion that in addition to Mark they also shared a lost source called the Q document (from "Quelle", the German word for "source);[81] its existence and use alongside Mark by the authors of Matthew and Luke seems the most convincing solution to the synoptic problem.[83]

Matthew and Luke contain some material unique to each, called the M source (or Special Matthew) for Matthew and the L source (Special Luke) for Luke.[81] This includes some of the best-known stories in the gospels, such as the birth of Christ and the Parable of the Good Samaritan (unique to Luke)[84] and the Parable of the Pearl of Great Price (unique to Matthew).[85]

The Hebrew scriptures were also an important source for all three, and for John.[86] Direct quotations number 27 in Mark, 54 in Matthew, 24 in Luke, and 14 in John, and the influence of the scriptures is vastly increased when allusions and echoes are included.[87] Half of Mark's gospel, for example, is made up of allusions to and citations of the scriptures, which he uses to structure his narrative and to present his understanding of the ministry, passion, death and resurrection of Jesus (for example, the final cry from the cross, "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?" is an exact quotation from Psalm 22:1[88]). Matthew contains all Mark's quotations and introduces around 30 more, sometimes in the mouth of Jesus, sometimes as his own commentary on the narrative,[89] and Luke makes allusions to all but three of the Old Testament books.[90]

Mark

[edit]Tradition holds that the gospel was written by Mark the Evangelist, St. Peter's interpreter, but its reliance on several underlying sources, varying in form and in theology, makes this unlikely.[91] Most scholars believe it was written shortly before or after the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the Second Temple in the year 70,[92] and internal evidence suggests that it probably originated in Syria among a Christian community consisting at least partly of non-Jews who spoke Greek rather than Aramaic and did not understand Jewish culture.[93]

Scholars since the 19th century have regarded Mark as the first of the gospels (called the theory of Marcan priority). Marcan priority led to the belief that Mark must be the most reliable of the gospels, but today there is a large consensus that the author of Mark was not intending to write history.[94] Mark preserves memories of real people (including the disciples), places and circumstances, but it is based on previously existing traditions which have been selected and arranged by the author to express his understanding of the significance of Jesus.[93]

In 1901 William Wrede demonstrated that Mark was not a simple historical account of the life of Jesus but a work of theology compiled by an author who was a creative artist.[95] Among the works that the author of Mark may have drawn from include the Elijah-Elisha narrative in the Book of Kings and the Pauline letters, notably 1 Corinthians, as well as the works of Homer.[96] According to Adam Winn, Mark is a counter-narrative to the myth of Imperial rule crafted by Vespasian.[97]

Advancing a minority view among scholars, Maurice Casey argued that Mark's gospel contains traces of literal translations of Aramaic sources, and that this implies, in some cases, a Sitz im Leben in the lifetime of Jesus and a very early date for the gospel.[98]

Matthew and Luke

[edit]The consensus of scholars dates Matthew and Luke to 80-90 AD.[99][note 5] The scholarly consensus is that Matthew originated in a "Matthean community" in the city of Antioch, located in modern-day Turkey;[100] Luke was written in a large city west of Judaea,[101] for an educated Greek-speaking audience.[102] Scholars doubt that the authors were the apostles Matthew and Luke: it seems unlikely, for example, that Matthew would rely so heavily on Mark if its author had been an eyewitness to Jesus's ministry,[103] or that the Acts of Apostles (by the same author as the gospel of Luke) would so frequently contradict the Pauline letters if its author had been Paul's companion,[101][104] though most scholars still believe the author of Luke-Acts met Paul.[105] Instead, the two took for their sources the gospel of Mark (606 of Matthew's verses are taken from Mark, 320 of Luke's),[106] the Q source, and the "special" material of M and L.

Q (Quelle)

[edit]Mark has 661 verses, 637 of which are reproduced in Matthew and/or Luke.[106] Matthew and Luke share a further 200 verses (roughly) which are not taken from Mark: this is called the Q source.[106][note 6] Q is usually dated about a decade earlier than Mark;[107] some scholars argue that it was a single written document, others for multiple documents, and others that there was a core written Q accompanied by an oral tradition.[108] Despite ongoing debate over its exact content - some Q materials in Matthew and Luke are identical word for word, but others are substantially different - there is general consensus about the passages that belong to it.[109] It has no passion story and no resurrection, but the Aramaic form of some sayings suggests that its nucleus reaches back to the earliest Palestinian community and even the lifetime of Jesus.[110]

Identifying the community of Q and the circumstances in which it was created and used is difficult, but it probably originated in Galilee, in a movement in opposition to the leadership in Jerusalem, as a set of short speeches relating to specific occasions such as covenant-renewal, the commissioning of missionaries, prayers for the Kingdom of God, and calling down divine judgement on their enemies, the Pharisees.[111] A large majority of scholars consider it to be among the oldest and most reliable material in the gospels.[112]

M and L (Special Matthew and Special Luke)

[edit]The premise that Matthew and Luke used sources in addition to Mark and Q is fairly widely accepted, although many details are disputed, including whether they were written or oral, or the invention of the gospel authors, or Q material that happened to be used by only one gospel, or a combination of these.[113]

John

[edit]The Gospel of John is a relatively late theological document containing little accurate historical information that is not found in the three synoptic gospels, which is why most historical studies have been based on the earliest sources Mark and Q.[114] Nonetheless, since the third quest, John's gospel is seen as having more reliability than previously thought or sometimes even more reliable than the synoptics.[82][115][116][117] It speaks of an unnamed "disciple whom Jesus loved" as the source of its traditions, but does not say specifically that he is its author;[118] Christian tradition identifies him as John the Apostle, but the majority of modern scholars have abandoned this or hold it only tenuously.[119][note 7] Most scholars believe it was written c. 90–110 AD,[120] at Ephesus in Anatolia (although other possibilities are Antioch, Northern Syria, Judea and Alexandria)[121] and went through two or three "edits" before reaching its final form, although a minority continue to support unitary composition.[122][120] There has been a decrease in arguing for the existence of hypothetical sources behind the Gospel of John in scholarship.[123]

The fact that the format of John follows that set by Mark need not imply that the author knew Mark, for there are no identical or almost-identical passages; rather, this was most probably the accepted shape for a gospel by the time John was written.[124] Nevertheless, John's discourses are full of synoptic-like material: some scholars think this indicates that the author knew the synoptics, although others believe it points instead to a shared base in the oral tradition.[125] John nevertheless differs radically from them:[126][127]

| Synoptics | John |

|---|---|

| Begin with the virgin conception (virgin birth - Matthew and Luke only) | Begin with incarnation of the preexistent Logos/Word |

| Jesus visits Jerusalem only in the last week of his life; only one Passover | Jesus active in Judea for much of his mission; three Passovers |

| Jesus speaks little of himself | Jesus speaks much of himself, notably in the "I am" statements |

| Jesus calls for faith in God | Jesus calls for faith in himself |

| Jesus's central theme is the Kingdom of God | Jesus rarely mentions the Kingdom of God |

| Jesus preaches repentance and forgiveness | Jesus never mentions repentance, and mentions forgiveness only once (John 20:23) |

| Jesus speaks in aphorisms and parables | Jesus speaks in lengthy dialogues |

| Jesus rarely mentions eternal life | Jesus regularly mentions eternal life |

| Jesus shows strong concern for the poor and sinners | Jesus shows little concern for the poor and sinners |

| Jesus frequently exorcises demons | Jesus never exorcises demons |

Texts

[edit]

Textual criticism resolves questions arising from the variations between texts: put another way, it seeks to decide the most reliable wording of a text.[15] Ancient scribes made errors or alterations (such as including non-authentic additions).[128] In attempting to determine the original text of the New Testament books, some modern textual critics have identified sections as additions of material, centuries after the gospel was written. These are called interpolations. In modern translations of the Bible, the results of textual criticism have led to certain verses, words and phrases being left out or marked as not original.

For example, there are a number of Bible verses in the New Testament that are present in the King James Version (KJV) but are absent from most modern Bible translations. Most modern textual scholars consider these verses interpolations (exceptions include advocates of the Byzantine or Majority text). The verse numbers have been reserved, but without any text, so as to preserve the traditional numbering of the remaining verses. The biblical scholar Bart D. Ehrman notes that many current verses were not part of the original text of the New Testament. "These scribal additions are often found in late medieval manuscripts of the New Testament, but not in the manuscripts of the earlier centuries," he adds. "And because the King James Bible is based on later manuscripts, such verses "became part of the Bible tradition in English-speaking lands."[129] He notes, however, that modern English translations, such as the New International Version, were written by using a more appropriate textual method.[130]

Most modern Bibles have footnotes to indicate passages that have disputed source documents. Bible Commentaries also discuss these, sometimes in great detail. While many variations have been discovered between early copies of biblical texts, most of these are variations in spelling, punctuation, or grammar. Also, many of these variants are so particular to the Greek language that they would not appear in translations into other languages.[131] Three of the most important interpolations are the last verses of the Gospel of Mark[132][133][134] the story of the adulterous woman in the Gospel of John,[135][136][137] and the explicit reference to the Trinity in 1 John to have been a later addition.[138][139]

The New Testament has been preserved in more than 5,800 fragmentary Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts and 9,300 manuscripts in various other ancient languages including Syriac, Slavic, Ethiopic and Armenian. Not all biblical manuscripts come from orthodox Christian writers. For example, the Gnostic writings of Valentinus come from the 2nd century AD, and these Christians were regarded as heretics by the mainstream church.[140] The sheer number of witnesses presents unique difficulties, although it gives scholars a better idea of how close modern bibles are to the original versions.[140] Bruce Metzger says "The more often you have copies that agree with each other, especially if they emerge from different geographical areas, the more you can cross-check them to figure out what the original document was like. The only way they'd agree would be where they went back genealogically in a family tree that represents the descent of the manuscripts."[131]

In "The Text Of The New Testament", Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland compare the total number of variant-free verses, and the number of variants per page (excluding spelling errors), among the seven major editions of the Greek NT (Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, Bover and Nestle-Aland), concluding that 62.9%, or 4,999/7,947, are in agreement.[141] They concluded, "Thus in nearly two-thirds of the New Testament text, the seven editions of the Greek New Testament which we have reviewed are in complete accord, with no differences other than in orthographical details (e.g., the spelling of names). Verses in which any one of the seven editions differs by a single word are not counted. ... In the Gospels, Acts, and Revelation the agreement is less, while in the letters it is much greater"[141] Per Aland and Aland, the total consistency achieved in the Gospel of Matthew was 60% (642 verses out of 1,071), the total consistency achieved in the Gospel of Mark was 45% (306 verses out of 678), the total consistency achieved in the Gospel of Luke was 57% (658 verses out of 1,151), and the total consistency achieved in the Gospel of John was 52% (450 verses out of 869).[141] Almost all of these variants are minor, and most of them are spelling or grammatical errors. Almost all can be explained by some type of unintentional scribal mistake, such as poor eyesight. Very few variants are contested among scholars, and few or none of the contested variants carry any theological significance. Modern biblical translations reflect this scholarly consensus where the variants exist, while the disputed variants are typically noted as such in the translations.[130]

A quantitative study on the stability of the New Testament compared early manuscripts to later manuscripts, up to the Middle Ages, with the Byzantine manuscripts, and concluded that the text had more than 90% stability over this time period.[142] It has been estimated that only 0.1% to 0.2% of the New Testament variants impact the meaning of the texts in any significant fashion.[142]

Individual units

[edit]Authors such as Raymond Brown point out that the Gospels contradict each other in various important respects and on various important details.[143] W. D. Davies and E. P. Sanders state that: "on many points, especially about Jesus' early life, the evangelists were ignorant … they simply did not know and, guided by rumour, hope or supposition, did the best they could".[144]

Preexistence of Jesus

[edit]The gospel of John begins with a statement that the Logos existed from the beginning, and was God.[why?]

Genealogy, nativity and childhood of Jesus

[edit]The genealogy, birth and childhood of Jesus appear only in Matthew and Luke, and are ascribed to Special Matthew and Special Luke. Only Luke and Matthew have nativity narratives. Modern critical scholars consider both to be non-historical.[145][146][147] Many biblical scholars view the discussion of historicity as secondary, given that gospels were primarily written as theological documents rather than historical accounts.[148][149][150][151]

The nativity narratives found in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 1:1–17) and the Gospel of Luke (Luke 3:23–38) give a genealogy of Jesus, but the names, and even the number of generations, differ between the two. Some authors have suggested that the differences are the result of two different lineages, Matthew's from King David's son, Solomon, to Jacob, father of Joseph, and Luke's from King David's other son, Nathan, to Heli, father of Mary and father-in-law of Joseph.[152] However, Geza Vermes argues that Luke makes no mention of Mary, and questions what purpose a maternal genealogy would serve in a Jewish setting.[153]

Dating the birth of Jesus

[edit]Both Luke and Matthew date Jesus' birth to within the rule of King Herod the Great, who died in 4BC.[154][155] However the Gospel of Luke also dates the birth ten years after Herod's death, during the census of Quirinius in 6 AD described by the historian Josephus.[154] Raymond E. Brown notes that "most critical scholars acknowledge a confusion and misdating on Luke's part."[156]

Teachings of Jesus

[edit]According to John P. Meier, only a few of the parables can be attributed with confidence to the historical Jesus, although other scholars disagree.[157] Meier argues that most of them come from the M and L sources (rather than Mark or Q), but marked by the special language and theology of each of those gospels; this leads to the conclusion that they are not the original words of Jesus, but have been reworked by the gospel-authors.[158]

Passion narrative

[edit]The entry of Jesus into Jerusalem recalls the entry of Judas Maccabeus; the Last Supper is mentioned only in the synoptics.[159]

Death of Judas

[edit]There is a contradiction regarding the death of Judas Iscariot with the account of his death in Acts differing from the one given in Matthew.[160] In Matthew 27:3–8, Judas returns the bribe he has been given for handing over Jesus, throwing the money into the temple before he hangs himself. The temple priests, unwilling to return the defiled money to the treasury,[161] use it instead to buy a field known as the Potter's Field, as a plot in which to bury strangers. In Acts 1:18 Peter says that Judas used the bribe money to buy the field himself, and his death is attributed to injuries from having fallen in this field. Some apologists argue that the contradictory stories can be reconciled.[162][163]

Archaeology and geography

[edit]

Archaeological tools are very limited with respect to questions of existence of any specific individuals from the ancient past.[164] According to Eric Cline, there is no direct archaeological evidence of the existence of a historical Jesus, any of the apostles, or the majority of people in antiquity.[164] Bart Ehrman states that having no archeological evidence is not an argument for the non-existence of Jesus because we have no archaeological evidence from anyone else from Jesus's day either.[165] Craig Evans notes that archaeologists have some indirect information on how Jesus' life might have been from archaeological finds from Nazareth, the High Priest Caiaphas' ossuary, numerous synagogue buildings, and Jehohanan, a crucified victim who had a Jewish burial after execution.[166] Archeological findings from Nazareth refute claims by mythicists that Nazareth did not exist in the 1st century and also give credibility to brief passages in the Gospels on Jesus' time in Nazareth, his father's trade, and connection to places in Judea.[167] Archaeologists have uncovered a site in Capernaum which is traditionally believed, with "no definitive proof" and based only upon circumstantial evidence, to have been the House of Peter, and which may thus possibly have housed Jesus.[168] Some of the places mentioned in the gospels have been verified by archaeological evidence, such as the Pool of Bethesda,[169] the Pool of Siloam, and the Temple Mount platform extension by King Herod. A mosaic from a third century church in Megiddo mentions Jesus.[164] A geological study based on sediments near the Dead Sea indicate that an earthquake occurred around 31 AD ± 5 years, which plausibly coincides with the earthquake reported by Matthew 27 near the time of the crucifixion of Christ.[170][171] A statistical study of name frequency in the Gospels and Acts corresponded well with a population name distribution database from 330 BC - 200 AD and the works of Josephus, but did not fit well with ancient fictional works.[172]

See also

[edit]- Authority – Reliability of a text as a witness

- Bible version debate – Debate concerning the proper Bible version to use

- Biblical manuscript

- Christ myth theory – Fringe theory claiming that a historical Jesus did not exist

- Criticism of the Bible

- Development of the New Testament canon

- Gospel harmony – Compiling events of the biblical gospels

- Jesus in comparative mythology – Comparative mythology study of Jesus Christ

- Jesus Seminar – American biblical research project

- Life of Jesus – Life of Jesus as told in the New Testament

- Scholarly interpretation of Gospel elements

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ These criteria are the criterion of dissimilarity; the criterion of embarrassment; the criterion of multiple attestation; the criterion of cultural and historical congruency; the criterion of "Aramaisms".

- ^ Evans 1993, pp. 13–14: "First, the New Testament Gospels are now viewed as useful, if not essentially reliable, historical sources. Gone is the extreme skepticism that for so many years dominated gospel research. Representative of many is the position of E. P. Sanders and Marcus Borg, who have concluded that it is possible to recover a fairly reliable picture of the historical Jesus."

- ^ Historians often study the historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles when studying the reliability of the gospels, as it is the view of virtually all scholars that The Acts of the Apostles was written by the same author as the Gospel of Luke.[citation needed]

- ^ Allison: "Despite the required hesitation, my inference, after taking everything into account, remains conventional: our Synoptic writers thought that they were reconfiguring memories of Jesus, not inventing theological tales. Such a supposition, however, does nothing to clarify whether or not the evangelists were right about the mnemonic nature of their traditions."

- ^ Matthew and Luke both use Mark, composed around 70, as a source, and both show a knowledge of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 (Matthew 22:1-10 and Luke 19:43 and 21:20). These provide an earliest possible date for both gospels; for end-dates, the epistles of Ignatius of Antioch show a familiarity with the gospel of Matthew, and as Ignatius died during the reign of the Emperor Trajan (r.98-117), Matthew cannot have been written later than this; and Acts, which scholars agree was written by the author of Luke, shows no awareness of the letters of Paul, which were circulating widely by the end of the 1st century. See Sim (2008), pages 15-16, and Reddish (2011), pages 144-145.

- ^ The existence of the Q source is a hypothesis linked to the most popular explanation of the synoptic problem; other explanations of that problem do away with the need for Q, but are less widely accepted. See Delbert Burkett, "Rethinking the Gospel Sources: The unity or plurality of Q" (Volume 2), page 1.

- ^ For the circumstances which led to the tradition, and the reasons why the majority of modern scholars reject it, see Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, pp. 41–42

Citations

[edit]- ^ Grant 1963, ch. 10; Sanders 1995, p. 3; Leiva-Merikakis 1996; Blomberg 2007; Ehrman, Evans & Stewart 2020.

- ^ Ehrman 2011, pp. 256–257: "He certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees, based on certain and clear evidence."

- ^ Grant 2004, p. 200: "In recent years, 'no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non-historicity of Jesus' or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary."

- ^ Burridge & Gould 2004, p. 34: "There are those who argue that Jesus is a figment of the Church's imagination, that there never was a Jesus at all. I have to say that I do not know any respectable critical scholar who says that any more."

- ^ Powell 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Dunn 2003, p. 339 states of baptism and crucifixion that these "two facts in the life of Jesus command almost universal assent".

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-06-061662-5.

That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus [...] agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact.

- ^ James K. Beilby; Paul Rhodes Eddy, eds. (2009). "Introduction". The Historical Jesus: Five Views. IVP Academic. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-0830838684.

Contrary to previous times, virtually everyone in the field today acknowledges that Jesus was considered by his contemporaries to be an exorcist and a worker of miracles. However, when it comes to historical assessment of the miracles tradition itself, the consensus quickly shatters. Some, following in the footsteps of Bultmann, embrace an explicit methodological naturalism such that the very idea of a miracle is ruled out a priori. Others defend the logical possibility of miracle at the theoretical level, but, in practice, retain a functional methodological naturalism, maintaining that we could never be in possession of the type and/or amount of evidence that would justify a historical judgment in favor of the occurrence of a miracle. Still others, suspicious that an uncompromising methodological naturalism most likely reflects an unwarranted metaphysical naturalism, find such a priori skepticism unwarranted and either remain open to, or even explicitly defend, the historicity of miracles within the Jesus tradition.

- ^ Markus Bockmuehl (2001). "7. Resurrection". The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. Cambridge University Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0521796781.

Nevertheless, what is perhaps most surprising is the extent to which contemporary scholarly literature on the 'historical Jesus' has studiously ignored and downplayed the question of the resurrection...But even the more mainstream participants in the late twentieth-century 'historical Jesus' bonanza have tended to avoid the subject of the resurrection – usually on the pretext that this is solely a matter of 'faith' or of 'theology', about which no self-respecting historian could possibly have anything to say. Precisely that scholarly silence, however, renders a good many recent 'historical Jesus' studies methodologically hamstrung, and unable to deliver what they promise...In this respect, benign neglect ranks alongside dogmatic denial and naive credulity in guaranteeing the avoidance of historical truth.

- ^ Sanders, E. P. (2010). "Jesus Christ". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2015-05-03. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

The Synoptic Gospels, then, are the primary sources for knowledge of the historical Jesus

. - ^ Sanders 1995; Vermes 2004.

- ^ Licona, Michael R. (2016). Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn from Ancient Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 3.

- ^ Keener, Craig S. (2011). "Otho: A Targeted Comparison of Suetonius's Biography and Tacitus's History, with Implications for the Gospels' Historical Reliability". Bulletin for Biblical Research. 21 (3). Penn State University Press: 331–355. doi:10.2307/26424373. JSTOR 26424373.

- ^ a b Sanders 1995.

- ^ a b Wegner 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Paul Rhodes Eddy & Gregory A. Boyd, The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. (2008, Baker Academic). 309-262. ISBN 978-0801031144

- ^ Ehrman, Evans & Stewart 2020, pp. 12–18.

- ^ a b Blomberg 2009, p. 425.

- ^ Craig L. Blomberg, Historical Reliability of the Gospels (1986, Inter-Varsity Press).19–72.ISBN 978-0830828074

- ^ Paul Rhodes Eddy & Gregory A. Boyd, The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. (2008, Baker Academic).237–308. ISBN 978-0801031144

- ^ Blomberg 2009, p. 424.

- ^ Tuckett 2000, p. 522.

- ^ Graham Stanton, Jesus and Gospel. p.192.

- ^ Charles H. Talbert, What Is a Gospel? The Genre of Canonical Gospels pg 42 (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1977).

- ^ Litwa, M. David (2019). How the Gospels Became History: Jesus and Mediterranean Myths. Yale University Press. pp. 4, 11–12. ISBN 978-0300242638.

- ^ Keener, Craig S. (2019). Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4674-5676-0.

- ^ Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0-86012-006-6 pages 730–741

- ^ Leiva-Merikakis 1996.

- ^ a b Grant 1963, ch. 10.

- ^ Bauckham 2008, p. 117.

- ^ Sanders, EP (1996). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin. p. 3. ISBN 0140144994.

- ^ James D.G. Dunn, "Messianic Ideas and Their Influence on the Jesus of History," in The Messiah, ed. James H. Charlesworth. pp. 371–372. Cf. James D.G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered.

- ^ a b Simpson, Benjamin I. (April 1, 2014). "review of The Historiographical Jesus. Memory, Typology, and the Son of David". The Voice. Dallas Theological Seminary.

- ^ Le Donne, Anthony (2018). Jesus: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. p. 212. ISBN 978-1786071446.

- ^ Allison, Dale (2010). Constructing Jesus: Memory, Imagination, and History. Baker Academic. p. 2-8, 8-9, 16-18, 20, 23-26, 33-43. ISBN 978-0801048753.

- ^ Rodriguez, Rafael (2014). "Jesus as his Friends Remembered Him". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus: 224-244. doi:10.1163/17455197-01203004.

- ^ Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig (1998). Authenticating the Words of Jesus & Authenticating the Activities of Jesus, Volume 2 Authenticating the Activities of Jesus. Brill. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-9004113022.

- ^ [1] Archived 2014-04-04 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 15nov2010

- ^ Keith, Chris (2011). "Memory and Authenticity: Jesus Tradition and What Really Happened". Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und Kunde der Älteren Kirche (102.2): 172, 176. doi:10.1515/zntw.2011.011.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2017). "The Synoptic Problem, Ancient Media, and the Historical Jesus: A Response". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 15 (2-3): 257. doi:10.1163/17455197-01502006.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2011). "Memory and Authenticity: Jesus Tradition and What Really Happened". Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und Kunde der Älteren Kirche (102.2): 166. doi:10.1515/zntw.2011.011.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2019). Memory and the Jesus Tradition. T&T Clark. pp. 209–216. ISBN 978-0567690036.

- ^ Kirk, Alan (2017). "The Synoptic Problem, Ancient Media, and the Historical Jesus: A Response". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 15 (2-3): 257. doi:10.1163/17455197-01502006.

- ^ Redman, Judy (13 December 2015). "Alan Kirk on Cognition, Commemoration and Tradition (3) - memory, tradition & historiography". Judy's research blog. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ a b Keener, Craig (2019). Christobiography: Memory, History, and the Reliability of the Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802876751.

- ^ Norman Perrin, Rediscovering the Teaching of Jesus 43.

- ^ Christopher Tuckett, "Sources and Method" in The Cambridge Companion to Jesus. ed. Markus Bockmuehl. 132.

- ^ Meier 2016, p. 168–171.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament:A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings.194-5.

- ^ The criteria for authenticity in historical-Jesus research: previous discussion and new proposals, by Stanley E. Porter, pg. 118

- ^ The criteria for authenticity in historical-Jesus research: previous discussion and new proposals, by Stanley E. Porter, pg. 119

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman, The New Testament:A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings.193.

- ^ Stanley E. Porter, The Criteria for Authenticity in Historical-Jesus Research: previous discussion and new proposals.127.

- ^ "Historical Jesus Scholarship and Christians". The Bart Ehrman Blog. 29 May 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ Reddish 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Burkett 2019, pp. 128–29.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Martens 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, pp. 7, 10, 14.

- ^ Horsley, Richard (2006). Performing the Gospel: Orality, Memory, and Mark. Augsburg Books. p. 104-46. ASIN B000SELH00.

- ^ Ferda, Tucker (2024). Jesus and His Promised Second Coming: Jewish Eschatology and Christian Origins. Eerdmans. p. 282. ISBN 9780802879905.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 13–40.

- ^ Dunn 2013, pp. 55, 223, 279–280, 309.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Evans, Craig (2016). "Mythicism and the Public Jesus of History". Christian Research Journal. 39 (5).

- ^ a b Ehrman 2013, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey by Craig L. Blomberg 2009 ISBN 0805444823 pp. 441-442

- ^ The Jesus legend: a case for the historical reliability of the synoptic gospels by Paul R. Eddy, et al 2007 ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 pp. 202, 204, 209-228

- ^ Ehrman 2005, p. 235: "Why then do we call them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? Because sometime in the second century, when proto-orthodox Christians recognized the need for apostolic authorities, they attributed these books to apostles (Matthew and John) and close companions of apostles (Mark, the secretary of Peter; and Luke, the traveling companion of Paul). Most scholars today have abandoned these identifications,11 and recognize that the books were written by otherwise unknown but relatively well-educated Greek-speaking (and writing) Christians during the second half of the first century."

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Eve 2014, p. 135.

- ^ Bellinzoni 2016, p. 336.

- ^ Blomberg 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Sanders 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Nolan, Albert (2001). Jesus Before Christianity. Orbis books. p. 13. ISBN 9781626984929.

- ^ Allison, Dale (2010). Constructing Jesus: Memory, Imagination, and History. Baker Academic. p. 459. ISBN 978-0801035852.

- ^ Dunn, James (2017). Who Was Jesus? (Little Books of Guidance). Church Publishing. p. 4. ISBN 978-0898692488.

- ^ Puskas & Robbins 2011, pp. 86, 89.

- ^ Reddish 2011, pp. 27, 29.

- ^ a b c Reid 1996, p. 18.

- ^ a b "Historical Criticism". The Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. 2008. p. 283. ISBN 9780415880886.

- ^ Tiwald 2020, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Meier 2016, p. 200.

- ^ Isaak 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Yu Chui Siang Lau 2010, p. 159.

- ^ Valantasis, Bleyle & Haugh 2009, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Moyise 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Kimball 1994, p. 48.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Reddish 2011, p. 74.

- ^ a b Schroter 2010, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Williamson 1983, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Strickland & Young 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Nelligan 2015, p. xivxv.

- ^ Winn 2018, p. 45.

- ^ Casey 1999, pp. 86, 136.

- ^ Reddish 2011, p. 144.

- ^ Sim 2008, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Green 1995, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Burkett 2019, p. 177.

- ^ Ehrman 2005, pp. 172, 235.

- ^ Keener, Craig (2015). Acts: An Exegetical Commentary (Volume 1). Baker Academic. p. 402. ISBN 978-0801039898.

- ^ a b c Augsburger 2004, p. unpaginated.

- ^ Moyise 2011, p. 87.

- ^ Burkett 2009, p. 33ff.

- ^ Gillman 2007, p. 1112.

- ^ Strecker 2012, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Burkett 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Powell 1998, p. 38.

- ^ Jones 2011, pp. 10, 17.

- ^ Casey 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Davies, W. D.; Sanders, E.P. (2008). "20. Jesus: From the Jewish Point of View". In Horbury, William; Davies, W.D.; Sturdy, John (eds.). The Cambridge History of Judaism. Volume 3: The Early Roman period. Cambridge Univiversity Press. p. 620. ISBN 9780521243773.

- ^ The Jesus Handbook. William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2022. pp. 138–140. ISBN 9780802876928.

- ^ Blomberg, Craig (2011). The Historical Reliability of John's Gospel: Issues and Commentary. IVP Academic. ISBN 0830838716.

- ^ Burkett 2019, p. 218.

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

- ^ a b Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Aune 2003, p. 243.

- ^ Edwards 2015, p. ix.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2020). The Gospel as Manuscript: An Early History of the Jesus Tradition as Material Artifact. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0199384372.

- ^ Dunn 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Dunn 2011, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Burkett 2019, p. 218.

- ^ Dunn 2011, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Ehrman 2005b, p. 46.

- ^ Ehrman 2005b, p. 265.

- ^ a b Ehrman 2005b, ch. 3.

- ^ a b Strobel, Lee. "The Case for Christ". 1998. Chapter three, when quoting biblical scholar Bruce Metzger

- ^ Guy D. Nave, The role and function of repentance in Luke-Acts,p. 194

- ^ John Shelby Spong, "The Continuing Christian Need for Judaism", Christian Century September 26, 1979, p. 918. see "The Continuing Christian Need for Judaism". Archived from the original on 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Feminist companion to the New Testament and early Christian writings, Volume 5, by Amy-Jill Levine, Marianne Blickenstaff, pg. 175

- ^ "NETBible: John 7". Bible.org. Archived from the original on 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2009-10-17. See note 139 on that page.

- ^ Keith, Chris (2008). "Recent and Previous Research on the Pericope Adulterae (John 7.53–8.11)". Currents in Biblical Research. 6 (3): 377–404. doi:10.1177/1476993X07084793. S2CID 145385075.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, "Pericope adulterae".

- ^ Ehrman 2005b, p. 166.

- ^ Bruce Metzger "A Textual Commentary on the New Testament", Second Edition, 1994, German Bible Society

- ^ a b Bruce, F.F. (1981). P 14. The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?. InterVarsity Press

- ^ a b c K. Aland and B. Aland, "The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions & to the Theory & Practice of Modern Textual Criticism", 1995, op. cit., p. 29-30.

- ^ a b Heide, K. Martin (2011). "Assessing the Stability of the Transmitted Texts of the New Testament and the Shepherd of Hermas". In Stewart, Robert B. (ed.). Bart D. Ehrman & Daniel B. Wallace in Dialogue: The Reliability of the New Testament. Fortress Press. pp. 134–138, 157–158. ISBN 9780800697730.

- ^ Brown, Raymond Edward (1999-05-18). The Birth of the Messiah: A Commentary on the Infancy Narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library). Yale University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-300-14008-8.

- ^ W.D Davies and E. P. Sanders, 'Jesus from the Jewish point of view', in The Cambridge History of Judaism ed William Horbury, vol 3: the Early Roman Period, 1984.

- ^ Vermes, Géza (2006-11-02). The Nativity: History and Legend. Penguin Books Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-14-102446-2.

- ^ Sanders 1995, pp. 85–88.

- ^ Marcus Borg, 'The Meaning of the Birth Stories' in Marcus Borg, N T Wright, The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions (Harper One, 1999) page 179: "I (and most mainline scholars) do not see these stories as historically factual."

- ^ Interpreting Gospel Narratives: Scenes, People, and Theology by Timothy Wiarda 2010 ISBN 0-8054-4843-8 pp. 75–78

- ^ Jesus, the Christ: Contemporary Perspectives by Brennan R. Hill 2004 ISBN 1-58595-303-2 p. 89

- ^ The Gospel of Luke by Timothy Johnson 1992 ISBN 0-8146-5805-9 p. 72

- ^ Recovering Jesus: the witness of the New Testament Thomas R. Yoder Neufeld 2007 ISBN 1-58743-202-1 p. 111

- ^ Warren, Tony. "Is there a Contradiction in the Genealogies of Luke and Matthew?" Archived 2012-11-14 at the Wayback Machine Created 2/2/95 / Last Modified 1/24/00. Accessed 4 May 2008.

- ^ Geza Vermes, The Nativity: History and Legend, (Penguin, 2006), page 42.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of theology: a concise Sacramentum mundi by Karl Rahner 2004 ISBN 0-86012-006-6 p. 731

- ^ Blackburn, Bonnie; Holford-Strevens, Leofranc (2003). The Oxford companion to the Year: An exploration of calendar customs and time-reckoning. Oxford University Press. p. 770. ISBN 978-0-19-214231-3.

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, An Adult Christ at Christmas: Essays on the Three Biblical Christmas Stories Archived 2016-08-21 at the Wayback Machine, (Liturgical Press, 1988), p. 17.

- ^ Meier 2016, p. 366.

- ^ Meier 2016, p. 369-370.

- ^ Smith 2010, p. 440.

- ^ Raymond E. Brown, An Introduction to the New Testament, p.114.

- ^ Alfred Edersheim Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, 5.xiv Archived 2017-12-22 at the Wayback Machine, 1883.

- ^ Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah, 5.xiv Archived 2017-12-22 at the Wayback Machine, 1883.

- ^ Inter-Varsity Press New Bible Commentary 21st Century edition p1071

- ^ a b c Cline, Eric H. (2009). Biblical Archaeology : A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195342635.

- ^ Ehrman 2013, p. 42: "This is not much of an argument against his existence, however, since there is no archaeological evidence for anyone else living in Palestine in Jesus's day except for the very upper-crust elite aristocrats, who are occasionally mentioned in inscriptions (we have no other archaeological evidence even for any of these). In fact, we don't have archaeological remains for any non-aristocratic Jew of the 20s CE, when Jesus would have been an adult."

- ^ Evans, Craig (2012-03-26). "The Archaeological Evidence For Jesus". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ Dark, Ken (2023). Archaeology of Jesus' Nazareth. Oxford University Press. pp. 159–160. ISBN 9780192865397.

- ^ "The House of Peter: The Home of Jesus in Capernaum?". Biblical Archaeology Society. 2018-04-22. Archived from the original on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- ^ James H. Charlesworth, Jesus and archaeology, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2006. p 566

- ^ "Is Jesus' Crucifixion Reflected in Soil Deposition?". Biblical Archaeology Society. June 4, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Jefferson B.; Schwab, Markus J.; Brauer, A. (23 December 2011). "An early first-century earthquake in the Dead Sea". International Geology Review. 54 (10): 1219–1228. doi:10.1080/00206814.2011.639996. S2CID 129604597.

- ^ Weghe, Luuk van de; Wilson, Jason (2024). "Why Name Popularity is a Good Test of Historicity: A Goodness-of-Fit Test Analysis on Names in the Gospels and Acts". Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus. 22 (2): 184–214.

Works cited

[edit]- Augsburger, Myron (2004). The Preacher's Commentary. Vol. 24: Matthew. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 978-1-4185-7444-4.

- Aune, David E. (2003). The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-21917-8.

- Bauckham, Richard (2008). Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6390-4.

- Bellinzoni, Arthur J. (2016). The New Testament: An Introduction to Biblical Scholarship. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-4982-3511-2.

- Blomberg, Craig L. (2007). The Historical Reliability of the Gospels (2nd ed.). InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-2807-4.

- Blomberg, Craig L. (2009). Jesus and the Gospels: An Introduction and Survey. B&H Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8054-4482-7.

- Burkett, Delbert (2009). Rethinking the Gospel Sources: The unity or plurality of Q, Volume 2. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-412-5.

- Burkett, Delbert (2019). An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-17278-4.

- Burridge, Richard A.; Gould, Graham (2004). Jesus Now and Then. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-0977-3.

- Casey, Maurice (1999). Aramaic Sources of Mark's Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-42587-2.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

- Cross, F. L.; Livingstone, E. A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-3931-2.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2011). Jesus, Paul, and the Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6645-5.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2013). The Oral Gospel Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-6782-7.

- Edwards, Ruth B. (2015). Discovering John: Content, Interpretation, Reception. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-7240-1.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005b). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-073817-4.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2011). Forged: Writing in the Name of God--Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-207863-6.

- Ehrman, Bart (2013). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperOne. ISBN 978-0-06-220644-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D.; Evans, Craig A.; Stewart, Robert B. (2020). Can we trust the Bible on the Historical Jesus?. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-26585-4.

- Evans, Craig (1993). "Life-of-Jesus Research and the Eclipse of Mythology". Theological Studies. 54: 3–36. doi:10.1177/004056399305400102.

- Eve, Eric (2014). Behind the Gospels: Understanding the Oral Tradition. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-8753-4.

- Gillman, John (2007). "Q Source". In Espín, Orlando O.; Nickoloff, James B. (eds.). An Introductory Dictionary of Theology and Religious Studies. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08457-3.

- Grant, Michael (2004). Jesus. Orion. ISBN 978-1-898799-88-7.

- Grant, Robert M. (1963). "Chapter 10: The Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts". A Historical Introduction to the New Testament. Harper and Row. Archived from the original on 21 June 2010 – via Religion-Online.org.

- Green, Joel (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Luke. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46932-6.

- Isaak, Jon (2011). New Testament Theology: Extending the Table. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-62189-254-0.

- Jones, Brice (2011). Matthean and Lukan Special Material. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-61097-737-1.

- Kimball, Charles (1994). Jesus' Exposition of the Old Testament in Luke's Gospel. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0-567-31908-1.

- Leiva-Merikakis, E. (1996). Fire of Mercy, Heart of the Word: Chapters 12-18. Vol. 2. Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-0-89870-976-6.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). The Gospel According to St John. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-8822-9.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Court, John M. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84127-081-4.

- Martens, Allan (2004). "Salvation Today: Reading Luke's Message for a Gentile Audience". In Porter, Stanley E. (ed.). Reading the Gospels Today. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0517-1.

- Meier, John P. (2016). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Volume V: Probing the Authenticity of the Parables. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-21647-9.

- Moyise, Steve (2011). Jesus and Scripture: Studying the New Testament Use of the Old Testament. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1-4412-3749-1.

- Nelligan, Thomas P. (2015). The Quest for Mark's Sources: An Exploration of the Case for Mark's Use of First Corinthians. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-62564-716-0.

- Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0-664-25703-3.

- Puskas, Charles B.; Robbins, C. Michael (2011). An Introduction to the New Testament (2nd ed.). Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-62189-331-8.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-5008-3.

- Reid, Barbara E. (1996). Choosing the Better Part?: Women in the Gospel of Luke. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-5494-1.

- Sanders, E. P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

- Schroter, Jens (2010). "The Gospel of Mark". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to The New Testament. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-567-37723-4.

- Sim, David C. (2008). "Reconstructing the Social and Religious Milieu of Matthew". In Van de Sandt, Huub; Zangenberg, Jurgen K. (eds.). Matthew, James, and Didache. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-358-6.

- Smith, Ian K. (2010). "Passion and Resurrection Narratives". In Harding, Mark; Nobbs, Alanna (eds.). The Content and the Setting of the Gospel Tradition. Eerdmans. pp. 437–455. ISBN 978-0-8028-3318-1.

- Strecker, Georg (2012). Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-080663-2.

- Strickland, Michael; Young, David M. (2017). The Rhetoric of Jesus in the Gospel of Mark. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-5064-3847-4.

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press.[ISBN missing]

- Tiwald, Markus (2020). The Sayings Source: A Commentary on Q. Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 978-3-17-037439-3.

- Tuckett, Christopher (2000). "Gospel, Gospels". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-90-5356-503-2.

- Valantasis, Richard; Bleyle, Douglas K.; Haugh, Dennis C. (2009). The Gospels and Christian Life in History and Practice. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-7069-6.

- Vermes, Geza (2004). The Authentic Gospel of Jesus. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-191260-8.

- Wegner, Paul D. (2006). A Student's Guide to Textual Criticism of the Bible. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-1-4185-7444-4.

- Williamson, Lamar (1983). Mark. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23760-8.

- Winn, Adam (2018). Reading Mark's Christology Under Caesar: Jesus the Messiah and Roman Imperial Ideology. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-8562-6.

- Yu Chui Siang Lau, Theresa (2010). "The Gospels and the Old Testament". In Harding, Mark; Nobbs, Alanna (eds.). The Content and the Setting of the Gospel Tradition. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3318-1.

Further reading

[edit]This "Further reading" section may need cleanup. (April 2024) |

- Barnett, Paul W. (1997). Jesus and the Logic of History. New Studies in Biblical Theology. Vol. 3. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-385-49449-6.

- Barnett, Paul W. (1987). Is the New Testament History?. Servant Publications. ISBN 978-0-89283-381-8.

- Bird, Michael F. (2014). The Gospel of the Lord: How the Early Church Wrote the Story of Jesus. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-1-4674-4031-8.

- Bock, Darrell L. (2002). Studying the Historical Jesus: A Guide to Sources and Methods. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2451-1.

- Brown, Raymond E. (1993). The Death of the Messiah: from Gethsemane to the Grave. Anchor Bible. ISBN 978-0-85111-512-2.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1-4267-2475-6.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983943-8.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2016). Jesus Before the Gospels. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-228523-2.

- Eve, Eric (2016). Writing the Gospels: Composition and Memory. SPCK. ISBN 978-0-281-07341-2.

- Fredriksen, Paula (2000). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08457-9.

- Gerhardsson, Birger (2001). The Reliability of the Gospel Tradition. Hendrickson. ISBN 978-1-56563-667-5.

- Gregory, Andrew (2006). "The Relationship of John and Luke Reconsidered". In Lierman, John (ed.). Challenging Perspectives on the Gospel of John. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-149113-9.

- Hultgren, Stephen (2014). Narrative Elements in the Double Tradition. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-089137-9.

- Keith, Chris (2012). "The Indebtedness of the Criteria Approach". In Keith, Chris; Le Donne, Anthony (eds.). Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-37723-4.

- Kloppenborg, John S. (2008). Synoptic Problems: Collected Essays. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-1-61164-058-8.

- Kloppenborg, John S. (2014). Q, the Earliest Gospel: An Introduction to the Original Stories and Sayings of Jesus. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-152617-6.

- Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Bock, Darrell L.; Chatraw, Josh (2014). Truth in a Culture of Doubt: Engaging Skeptical Challenges to the Bible. B&H Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4336-8227-8.

- Meier, John P., A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus, Doubleday,

- v. 1, The Roots of the Problem and the Person, 1991, ISBN 0-385-26425-9

- v. 2, Mentor, Message, and Miracles, 1994, ISBN 0-385-46992-6

- v. 3, Companions and Competitors, 2001, ISBN 0-385-46993-4

- v. 4, Law and Love ISBN 978-0300140965

- v. 5, Probing the Authenticity of the Parables ISBN 978-0300211900

- Powell, Mark Allan (2018). Introducing the New Testament: A Historical, Literary, and Theological Survey. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-1-4934-1313-3.

- Sanders, E. P. (1996). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014499-4.

- Schmidt, Karl Ludwig; Riches, John (2002). The Place of the Gospels in the General History of Literature. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-430-5.

- Senior, Donald (1996). What are they saying about Matthew?. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-3624-7.

- Senior, Donald (2001). "Directions in Matthean Studies". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study: Studies in Memory of William G. Thompson, S.J. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4673-0.

- Strauss, Mark L. (2011). Four Portraits, One Jesus: A Survey of Jesus and the Gospels. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0-310-86615-2.

- Thomas, Robert L. (2002). "Introduction". In Thomas, Robert L. (ed.). Three Views on the Origins of the Synoptic Gospels. Kregel Academic. ISBN 978-0-8254-9882-4.

- Tyson, Joseph B. (2006). Marcion and Luke-Acts: A Defining Struggle. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-650-7.

- Van Belle, Gilbert; Palmer, Sydney (2007). "John's Literary Unity and the Problem of Historicity". In Anderson, Paul N.; Just, Felix; Thatcher, Tom (eds.). John, Jesus, and History, Volume 1: Critical Appraisals of Critical Views. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-293-0.

- Wright, N.T. Christian Origins and the Question of God, a projected 6 volume series of which 3 have been published under:

- v. 1, The New Testament and the People of God. Augsburg Fortress Publishers: 1992.;

- v. 2, Jesus and the Victory of God. Augsburg Fortress Publishers: 1997.;

- v. 3, The Resurrection of the Son of God. Augsburg Fortress Publishers: 2003.

- Wright, N. T. (1996). The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering who Jesus was and is. IVP.[ISBN missing]

- Yamazaki-Ransom, Kazuhiko (2010). The Roman Empire in Luke's Narrative. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-36439-5.