Heated humidified high-flow therapy

| High-flow therapy | |

|---|---|

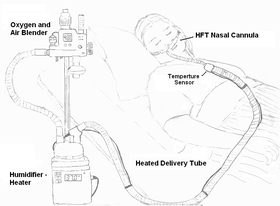

Illustration of a patient using HFT device | |

| Other names | High flow nasal cannula |

| ICD-10-PCS | Z99.81 |

Heated humidified high-flow therapy, often simply called high flow therapy , is a type of respiratory support that delivers a flow of medical gas to a patient of up to 60 liters per minute and 100% oxygen through a large bore or high flow nasal cannula. Primarily studied in neonates, it has also been found effective in some adults to treat hypoxemia and work of breathing issues. The key components of it are a gas blender, heated humidifier, heated circuit, and cannula.[1]

History

[edit]The development of heated humidified high flow started in 1999 with Vapotherm introducing the concept of high flow use with race horses.[2]

High flow was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in the early 2000s and used as an alternative to positive airway pressure for treatment of apnea of prematurity in neonates.[3] The term high flow is relative to the size of the patient which is why the flow rate used in children is done by weight as just a few liters can meet the inspiratory demands of a neonate unlike in adults[4] It has since become popular for use in adults for respiratory failure[5]

Mechanism

[edit]The traditional low flow system used for medical gas delivery is the Nasal cannula which is limited to the delivery of 1–6 L/min of oxygen or up to 15 L/min in certain types. This is because even with quiet breathing, the inspiratory flow rate at the nares of an adult usually exceeds 30 L/min. Therefore, the oxygen provided is diluted with room air during inspiration.[6] Being a high flow system means that it meets or exceeds the flow demands of the patient.

Oxygenation

[edit]Since it is a high flow system, it is able to maintain the wearers fraction of inhaled oxygen (FiO2) at the set rate because they shouldn't be entraining ambient air. However, this may not be the case in patients who are poorly compliant with the therapy and are actively breathing through their mouth.[7]

Ventilation

[edit]The flow can wash out some of the dead space in the upper airway. This can reduce slightly the amount of carbon dioxide rebreathed.[7]

There is a correlation of the flow rate to mean airway pressure and in some subjects there has been an increase in lung volumes and decrease in respiratory rate.[8] However, positive end expiratory pressure has only been measured at less 3 cmH2O meaning it is not able to provide close to what a closed ventilatory system could provide.[9] In neonates it has been found, however, with a good fit and mouth closed, it can provide end expiratory pressure comparable to nasal continuous positive airway pressure.[10]

Humidification

[edit]The higher the flow, the more important proper humidification and heating of the flow becomes to prevent tissue irritation and mucous drying. It has been found that long term use of flows of 20-25 L/min can help reduce symptoms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This is because, heat and humidity help mucociliary clearance.[11][12] This is the reason why high-flow therapy is assumed to help with mucus clearance better than other less humidified methodologies.

Medical use

[edit]

High-flow therapy is useful in patients that are spontaneously breathing but are in some type of respiratory failure. These are hypoxemic and certain cases of hypercapnic respiratory failure stemming from exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiolitis, pneumonia, and congestive heart failure are all possible situations where high-flow therapy may be indicated.[13]

Newborn babies

[edit]High-flow therapy has shown to be useful in neonatal intensive care settings for premature infants with Infant respiratory distress syndrome,[14] as it prevents many infants from needing more invasive ventilatory treatments.

Due to the decreased stress of effort needed to breathe, the neonatal body is able to spend more time utilizing metabolic efforts elsewhere, which causes decreased days on a mechanical ventilator, faster weight gain, and overall decreased hospital stay entirely.[15]

High-flow therapy has been successfully implemented in infants and older children. The cannula improves the respiratory distress, the oxygen saturation, and the patient's comfort. Its mechanism of action is the application of mild positive airway pressure and lung volume recruitment.[16]

Hypoxemic respiratory failure

[edit]In high-flow therapy, clinicians can deliver higher FiO2 than is possible with typical oxygen delivery therapy without the use of a non-rebreather mask or tracheal intubation.[17] Some patients requiring respiratory support for bronchospasm benefit using air delivered by high-flow therapy without additional oxygen.[18] Patients can speak during use of high-flow therapy. As this is a non-invasive therapy, it avoids the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Use of nasal high flow in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure does not affect mortality or length of stay either in hospital or in the intensive care unit. It can however reduce the need for tracheal intubation and escalation of oxygenation and respiratory support.[19][20]

Hypercapnic respiratory failure

[edit]Stable patients with hypercapnia on high-flow therapy have been found to have their carbon dioxide levels decrease similar amounts to noninvasive treatment, but evidence is still limited as to its efficacy and currently the practice guideline is still to use noninvasive ventilation for those with exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and acidosis.[21]

Other uses

[edit]Heated humidified high-flow therapy has been used in spontaneously breathing patients with during general anesthesia to facilitate surgery for airway obstruction.[22]

High flow therapy is useful in the treatment of sleep apnea.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ Nishimura M (April 2016). "High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Adults: Physiological Benefits, Indication, Clinical Benefits, and Adverse Effects". Respiratory Care. 61 (4): 529–541. doi:10.4187/respcare.04577. PMID 27016353. S2CID 11360190.

- ^ Waugh J. "High Flow Oxygen Delivery" (PDF). Trends in Noninvasive Respiratory Support: Continuum of Care. Clinical Foundations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- US patent (expired) 4722334, Blackmer RH, Hedman JW, "Method and apparatus for pulmonary and cardiovascular conditioning of racehorses and competition animals", issued 1988-02-02

- ^ Sreenan C, Lemke RP, Hudson-Mason A, Osiovich H (May 2001). "High-flow nasal cannulae in the management of apnea of prematurity: a comparison with conventional nasal continuous positive airway pressure". Pediatrics. 107 (5): 1081–1083. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.1081. PMID 11331690.

- ^ Ramnarayan P, Richards-Belle A, Drikite L, Saull M, Orzechowska I, Darnell R, et al. (April 2022). "Effect of High-Flow Nasal Cannula Therapy vs Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Following Extubation on Liberation From Respiratory Support in Critically Ill Children: A Randomized Clinical Trial". JAMA. 327 (16): 1555–1565. doi:10.1001/jama.2022.3367. PMC 8990361. PMID 35390113.

- ^ Spicuzza L, Schisano M (2020). "High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy as an emerging option for respiratory failure: the present and the future". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 11: 2040622320920106. doi:10.1177/2040622320920106. PMC 7238775. PMID 32489572.

- ^ Puddy A, Younes M (September 1992). "Effect of inspiratory flow rate on respiratory output in normal subjects". The American Review of Respiratory Disease. 146 (3): 787–789. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.787. PMID 1519864.

- ^ a b Möller W, Feng S, Domanski U, Franke KJ, Celik G, Bartenstein P, et al. (January 2017). "Nasal high flow reduces dead space". Journal of Applied Physiology. 122 (1): 191–197. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00584.2016. PMC 5283847. PMID 27856714.

- ^ Parke, Rachael L.; Bloch, Andreas; McGuinness, Shay P. (2015-10-01). "Effect of Very-High-Flow Nasal Therapy on Airway Pressure and End-Expiratory Lung Impedance in Healthy Volunteers". Respiratory Care. 60 (10): 1397–1403. doi:10.4187/respcare.04028. ISSN 0020-1324. PMID 26329355.

- ^ Helviz, Yigal; Einav, Sharon (2018-03-20). "A Systematic Review of the High-flow Nasal Cannula for Adult Patients". Critical Care. 22 (1): 71. doi:10.1186/s13054-018-1990-4. ISSN 1364-8535. PMC 5861611. PMID 29558988.

- ^ Dysart K, Miller TL, Wolfson MR, Shaffer TH (October 2009). "Research in high flow therapy: mechanisms of action". Respiratory Medicine. 103 (10): 1400–1405. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.04.007. PMID 19467849. (Review).

- ^ Rea H, McAuley S, Jayaram L, Garrett J, Hockey H, Storey L, et al. (April 2010). "The clinical utility of long-term humidification therapy in chronic airway disease". Respiratory Medicine. 104 (4): 525–533. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2009.12.016. PMID 20144858.

- ^ Hasani A, Chapman TH, McCool D, Smith RE, Dilworth JP, Agnew JE (2008). "Domiciliary humidification improves lung mucociliary clearance in patients with bronchiectasis". Chronic Respiratory Disease. 5 (2): 81–86. doi:10.1177/1479972307087190. PMID 18539721. S2CID 206736621.

- ^ Veenstra P, Veeger NJ, Koppers RJ, Duiverman ML, van Geffen WH (2022-10-05). "High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for admitted COPD-patients. A retrospective cohort study". PLOS ONE. 17 (10): e0272372. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1772372V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272372. PMC 9534431. PMID 36197917.

- ^ Shoemaker MT, Pierce MR, Yoder BA, DiGeronimo RJ (February 2007). "High flow nasal cannula versus nasal CPAP for neonatal respiratory disease: a retrospective study". Journal of Perinatology. 27 (2): 85–91. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211647. PMID 17262040. S2CID 25835575.

- ^ Holleman-Duray D, Kaupie D, Weiss MG (December 2007). "Heated humidified high-flow nasal cannula: use and a neonatal early extubation protocol". Journal of Perinatology. 27 (12): 776–781. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7211825. PMID 17855805.

- ^ Spentzas T, Minarik M, Patters AB, Vinson B, Stidham G (2009-10-01). "Children with respiratory distress treated with high-flow nasal cannula". Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 24 (5): 323–328. doi:10.1177/0885066609340622. PMID 19703816. S2CID 25585432.

- ^ Roca O, Riera J, Torres F, Masclans JR (April 2010). "High-flow oxygen therapy in acute respiratory failure". Respiratory Care. 55 (4): 408–413. PMID 20406507.

- ^ Waugh JB, Granger WM (August 2004). "An evaluation of 2 new devices for nasal high-flow gas therapy". Respiratory Care. 49 (8): 902–906. PMID 15271229.

- ^ Rochwerg B, Granton D, Wang DX, Helviz Y, Einav S, Frat JP, et al. (May 2019). "High flow nasal cannula compared with conventional oxygen therapy for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Intensive Care Medicine. 45 (5): 563–572. doi:10.1007/s00134-019-05590-5. PMID 30888444. S2CID 83463457.

- ^ Veenstra P, Veeger NJ, Koppers RJ, Duiverman ML, van Geffen WH (2022-10-05). "High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy for admitted COPD-patients. A retrospective cohort study". PLOS ONE. 17 (10): e0272372. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1772372V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0272372. PMC 9534431. PMID 36197917.

- ^ Spicuzza, Lucia; Schisano, Matteo (2020). "High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy as an emerging option for respiratory failure: the present and the future". Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease. 11: 204062232092010. doi:10.1177/2040622320920106. ISSN 2040-6223. PMC 7238775. PMID 32489572.

- ^ Booth AW, Vidhani K, Lee PK, Thomsett CM (March 2017). "SponTaneous Respiration using IntraVEnous anaesthesia and Hi-flow nasal oxygen (STRIVE Hi) maintains oxygenation and airway patency during management of the obstructed airway: an observational study". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 118 (3): 444–451. doi:10.1093/bja/aew468. PMC 5409133. PMID 28203745.

- ^ McGinley BM, Patil SP, Kirkness JP, Smith PL, Schwartz AR, Schneider H (July 2007). "A nasal cannula can be used to treat obstructive sleep apnea". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 176 (2): 194–200. doi:10.1164/rccm.200609-1336OC. PMC 1994212. PMID 17363769.