Roselle (plant)

| Roselle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Wave Hill, 2014 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Malvales |

| Family: | Malvaceae |

| Subfamily: | Malvoideae |

| Tribe: | Hibisceae |

| Genus: | Hibiscus |

| Species: | H. sabdariffa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hibiscus sabdariffa | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) is a species of flowering plant in the genus Hibiscus that is native to Africa, most likely West Africa. In the 16th and early 17th centuries it was spread to Asia and the West Indies, where it has since become naturalized in many places.[1] The stems are used for the production of bast fibre and the dried cranberry-tasting calyces are commonly steeped to make a popular infusion known by many names, including carcade.

Description

[edit]Roselle is an annual or perennial herb or woody-based subshrub, growing to 2–2.5 m (7–8 ft) tall. The leaves are deeply three- to five-lobed, 8–15 cm (3–6 in) long, arranged alternately on the stems.

The flowers are 8–10 cm (3–4 in) in diameter, white to pale yellow with a dark red spot at the base of each petal, and have a stout, conspicuous calyx at the base, 1–2 cm (0.39–0.79 in) wide, enlarging to 3–3.5 cm (1.2–1.4 in) and becoming fleshy and a deep crimson red as the fruit matures, which takes about six months.

Names

[edit]

Asia

[edit]Roselle is known as karkadeh (كركديه) in Arabic,[2] chin baung (ချဉ်ပေါင်) in Burmese,[3] luòshénhuā (洛神花) in Chinese,[4] Thai: กระเจี๊ยบ (RTGS: krachiap) in Thai,[5] ສົ້ມພໍດີ /sőm phɔː diː/ in Lao,[6] ស្លឹកជូរ /slɜk cuː/ សណ្តាន់ទេស /sɑndan tẹːh/, ម្ជូរបារាំង /məcuː baraŋ/,[7] or ម្ជូរព្រឹក /məcuː prɨk/ in Khmer, and cây quế mầu, cây bụp giấm, or cây bụt giấm in Vietnamese.

South Asia

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Roselle is known as chukur/chukai (চুকুর/চুকাই),[8] and amlamadhur (অম্লমধুর) in Bengali. It is called ya pung by the Marma people of Bangladesh's Chittagong Hill Tracts.

In north eastern India and environs, it is called tengamora (টেঙামৰা) by various indigenous ethnic groups of Assam.[9] In addition, it is known as hoilfa (হইলফা) in Sylheti, dachang or datchang by Atongs, mwita among the Bodo, amile among Chakmas mostly in Chittagong, gal•da among Garos, Khandrong among Tiwa, hanserong among Karbi (an indigenous group of Asaam), hantserup among Lotha of Nagaland. Other names are okhreo among Maos, sillo sougri among Meitei and belchanda (बेलचण्डा) among Nepalis. Anthur sen (roselle red) in Hakha Chin, lakher anthur in Mizo and hmiakhu saipa (roselle red) or matu hmiakhu in the Mara language are names used in Mizoram, India and Chin State, Myanmar.

In eastern and central India, roselle in Odia is known as kaaunria saga (କାଊଂରିଆ ଶାଗ) in Koraput and Malkangiri districts of Odisha, khata palanga (ଖଟାପାଳଙ୍ଗ) in the Jagatsinghpur and Cuttack districts and takabhendi (ଟକଭେଣ୍ଡି) in the Balasore district. In the Chota Nagpur region, it is called kudrum or dhepa saag in Nagpuri (Sadri). It is also known by other names in different languages of this region, like ipil jongor, which means "star fruit" in the Mundari language.

In southern and western India, it is known as pundi palle (ಪುಂಡಿ ಪಲ್ಯ) or pundi soppu (ಪುಂಡಿ ಸೊಪ್ಪು) in Kannada, mathippuli (മത്തിപ്പുളി) or pulivenda (പുളിവെണ്ട) in Malayalam,[10] ambadi (अंबाडी) in Maharashtra,[9] pulicha keerai (புளிச்சகீரை) in Tamil[9] and gongura (గోంగూర) in Telugu.

Australia

[edit]In Australia, roselle is known as the rosella or rosella fruit.[11] It is naturalised in Australia and its introduction is thought to have been from interactions with Makassar traders.[12][13] Australia also has a native rosella, Hibiscus heterophyllus, known as wyrrung to Koori aboriginal people in New South Wales.[14] It is indigenous to eastern parts of New South Wales and Queensland and is one of about 40 species of Hibiscus native to Australia.[15]

Africa

[edit]In West Africa, roselle is known as ìsápá among the Yoruba in southwest Nigeria and yakuwa by the Hausa people of northern Nigeria who also call the seeds gurguzu and the capsule cover zoborodo or zobo.[16][17][18] In Igbo which is spoken in Southern Nigeria, as well as Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea, it is called ojō or ọkwọrọ-ozo.

Among the Tiv people of Central Nigeria, the plant is called ashwe while the capsule is referred to as agbende ashwe.[19] It is primarily consumed as a soup in three forms: The leaves are either cooked, or steamed and crushed on a grinding stone, in which form it is considered a delicacy due to its preservation of the characteristic tang (slightly sour taste) of the leaves. The outer covering of the capsule (green variety) is also cooked as a soup which does not have the tang of the leaves. The red variant of the capsule are rarely (if ever) cooked, but instead boiled and the extract cooled and drunk (like tea or soda when sugar is added).[20] This form is known as zobo, which is actually a borrowed name, just as this method of preparation is borrowed. Traditionally the red variant was used as a dye to color wood, and similar materials.[21]

In Fula language, spoken in a number of countries across West and Middle Africa, roselle is known as chia or foléré.[9] It is known as bissap in Wolof, in Senegal.[22] In Dagbani, it is known as birili[23] and a sour seasoning made from the flowers is kananjuŋ.[24] It is called wegda in the Mossi language, one of four official regional languages spoken in Burkina Faso.[9]

In Middle Africa, roselle is called ngaï-ngaï[25] (from Lingala) in the Democratic Republic of Congo, while in the Central African Republic, it is dongö or ngbe in Sango.[26]

In East Africa, roselle is called kärkädē (ከርከዴ) in Amharic and Tigrinya,[27] while in Swahili, one of the official languages of the East African Community, it is named choya.

Americas

[edit]Roselle is also known as Florida Cranberry or Jamaica sorrel in the United States.[28] It is called saril or flor de Jamaica in Spanish across Central America.[29][30]

It is known as sorrel in many parts of the English-speaking Caribbean, including Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica and most of the islands in the West Indies.[31] In the French West Indies, it is known as groseille-pays, or as Gwozey-péi in Antillean Creole.[32]

In Brazil, it has a number of names, including vinagreira, and caruru-azedo, and is an important part of a dish regional to the state of Maranhão, Arroz de cuxá.[33][34]

Composition

[edit]Nutrition

[edit]| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 205 kJ (49 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

11.31 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.64 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.96 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[35] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[36] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phytochemicals

[edit]The Hibiscus leaves are a good source of polyphenolic compounds. The major identified compounds include neochlorogenic acid, chlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, caffeoylshikimic acid and flavonoid compounds such as quercetin, kaempferol and their derivatives.[37] The flowers are rich in anthocyanins, as well as protocatechuic acid. The dried calyces contain the flavonoids gossypetin, hibiscetine and sabdaretine. The major pigment is not daphniphylline.[38] Small amounts of myrtillin (delphinidin 3-monoglucoside), chrysanthenin (cyanidin 3-monoglucoside), and delphinidin are present. Roselle seeds are a good source of lipid-soluble antioxidants, particularly gamma-tocopherol.[39]

Uses

[edit]Culinary

[edit]In Bihar and Jharkhand roselle is also known as "kudrum" in local language. The bright red petal of the fruit is used for chutney which is sweet and sour in taste.

In Saputara region (near Maharashtra/Gujarat MP border), roselle is called khate fule also called as 'ambade fule' by local tribal language. The khate fule leaves are mixed with green chillies, salt, some garlic to prepare a chutney and bhaji which is served with jowar (sorghum) or bajra (millet) made bakho (a flat bread). This is eaten by tribals as breakfast to start their day. A dry dish or sukhi bajji is prepared with khate fule leaves.[citation needed]

In Andhra cuisine, roselle is called gongura and is extensively used. The leaves are steamed with lentils and cooked with dal. Another unique dish is prepared by mixing fried leaves with spices and made into a gongura pacchadi, the most famous dish of Andhra and Telangana often described as king of all Andhra foods.[citation needed]

In Manipuri, it is called Sougri and it is used as a vegetable. It is generally cooked without oil by boiling with some other herbs and dried fish and is a favorite of the Manipuri people. Almost every household has this plant in their homes.

In Burmese cuisine, called chin baung ywet (lit. 'sour leaf'), the roselle is widely used and considered affordable. It is perhaps the most widely eaten and popular vegetable in Myanmar.[40] The leaves are fried with garlic, dried or fresh prawns and green chili or cooked with fish. A light soup made from roselle leaves and dried prawn stock is also a popular dish.

Among the Paites tribe of the Manipur Hibiscus sabdariffa and Hibiscus cannabinus locally known as anthuk are cooked along with chicken, fish, crab or pork or any meat, and cooked as a soup as one of their traditional cuisines.[41]

In the Garo Hills of Meghalaya, it is known as galda and is consumed boiled with pork, chicken or fish. After monsoon, the leaves are dried and crushed into powder, then stored for cooking during winter in a rice powder stew, known as galda gisi pura. In the Khasi Hills of Meghalaya, the plant is locally known as jajew, and the leaves are used in local cuisine, cooked with both dried and fresh fish. The Bodos and other indigenous Assamese communities of north east India cook its leaves with fish, shrimp or pork along with boiling it as vegetables which is much relished. Sometimes they add native lye called karwi or khar to bring down its tartness and add flavour.

In the Philippines, the leaves and flowers are used to add sourness to the chicken dish tinola (chicken stew).[42]

In Vietnam, the young leaves, stems and fruits are used for cooking soups with fish or eel.[43]

In Mali, the dried and ground leaves, also called djissima, are commonly used in Songhaï cuisine, in the regions of Timbuktu, Gao and their surroundings. It is the main ingredient in at least two dishes, one called djissima-gounday, where rice is slowly cooked in a broth containing the leaves and lamb, and the other dish is called djissima-mafé, where the leaves are cooked in a tomato sauce, also including lamb. Note that djissima-gounday is also considered an affordable dish.

In Namibia, it is called mutete, and it is consumed by people from the Kavango region in northeastern Namibia.

In the central African nations of Congo-Kinshasa, Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon the leaves are referred to as oseille or ngaï-ngaï, and are used puréed, or in a sauce, often with fish and/or aubergines.

Beverage

[edit]In the Caribbean, a drink is made from the roselle fruit (the calyces with the seed pods removed). It is prepared by boiling fresh, frozen or dried roselle fruit in water for 8 to 10 minutes (or until the water turns red), then adding sugar. Bay leaves and cloves may also be added during boiling.[44] It is often served chilled. This is done in St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Antigua, Barbados, Belize, St. Lucia, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, the US Virgin Islands and St. Kitts and Nevis where the plant or fruit is called sorrel. The drink is one of several inexpensive beverages (aguas frescas) commonly consumed in Mexico and Central America; they are typically made from fresh fruits, juices or extracts. In Mexican restaurants in the US, the beverage is sometimes known simply as Jamaica (Spanish pronunciation: [xaˈmajka] hah-MY-cah). It is very popular in Trinidad and Tobago especially as a seasonal drink at Christmas where cinnamon, cloves and bay leaves are preferred to ginger.[45] It is also popular in Jamaica, usually flavored with rum.

In Ghana, Mali, Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and Benin, calyces are used to prepare cold, sweet drinks popular in social events, often mixed with mint leaves, dissolved menthol candy, and/or fruit flavors.

The Sudanese karkadeh (كركديه) is a cold drink made by soaking the dried roselle calyces in cold water overnight in a refrigerator with sugar and some lemon or lime juice added. It is then consumed with or without ice cubes after the flowers have been strained.[46] In Lebanon, toasted pine nuts are sometimes added.

Roselle is used in Nigeria to make a refreshing drink known as zobo and natural fruit juices of pineapple and watermelon are added. Ginger is also sometimes added to the refreshing drink.[47]

In the US, a beverage known as hibiscus cooler is made from the tea, a sweetener, and sometimes juice of apple, grape or lemon. The beverage is sold by some juice companies.[48] With the increasing popularity of Mexican cuisine in the US, the calyces are sold in bags usually labeled "flor de Jamaica" and have long been available in health food stores in the U.S. for making tea. In addition to being a popular homemade drink, Jarritos, a popular brand of Mexican soft drinks, makes a flor de Jamaica flavored carbonated beverage. Imported Jarritos can be readily found in the U.S. Beverages made from the roselle fruit are included in a category of "red drinks" associated with West Africa consumed by African Americans.[49] Such red drinks, now usually carbonated soft drinks, are commonly served in soul food restaurants and at African-American social events, including Juneteenth, a celebration of the emancipation of slaves.[49][50]

In the UK, the dried calyces and ready-made sorrel syrup are widely and cheaply available in Caribbean and Asian grocers. The fresh calyces are imported mainly during December and January to make Christmas and New Year infusions, which are often made into cocktails with rum. They are very perishable, rapidly developing fungal rot, and need to be used soon after purchase — unlike the dried product, which has a long shelf-life.

In Africa, especially the Sahel, roselle is commonly used to make a sugary herbal tea that is sold on the street. The dried flowers can be found in every market. Roselle tea is quite common in Italy where it spread during the first decades of the 20th century as a typical product of the Italian colonies. The Carib Brewery, a Trinidad and Tobago brewery, produces a "shandy sorrel" in which the tea is combined with beer.

In Thailand, roselle is generally drunk as a cool drink,[51] and it can be made into a wine.

Roselle flowers are commonly found in commercial herbal teas, especially teas advertised as berry-flavoured, as they give a bright red colouring to the drink.

Roselle flowers are sold as wild hibiscus flowers in syrup in Australia as a gourmet product. Recipes include filling them with goats cheese; serving them on baguette slices baked with brie; and placing one plus a little syrup in a champagne flute before adding the champagne — the bubbles cause the flower to open.

In Dodoma, Tanzania, roselle juice is brewed to make roselle wine famous by the name of choya.

Preserves

[edit]In Nigeria, roselle jam has been made since colonial times and is still sold regularly at community fetes and charity stalls. It is similar in flavour to plum jam, although more acidic. It differs from other jams in that the pectin is obtained from boiling the interior buds of the roselle flowers. It is thus possible to make rosella jam with nothing but roselle buds and sugar.[52]

In Burma, the buds of the roselle are made into 'preserved fruits' or jams. Depending on the method and the preference, the seeds are removed or included. The jams, made from roselle buds and sugar, are red and tangy.

In India, Roselle is commonly made into a type of pickle.

"Sorrel jelly" is manufactured in Trinidad.

Roselle jam is made in Queensland, Australia as a home-made or speciality product sold at fetes and other community events.[53]

In India, the plant is primarily cultivated for the production of bast fibre used in cordage, made from its stem.[54] The fibre may be used as a substitute for jute in making burlap.[55] Hibiscus, specifically roselle, has been used in folk medicine as a diuretic and mild laxative.[56]

The red calyces of the plant are increasingly exported to the United States and Europe, particularly Germany, where they are used as food colourings. It can be found in markets (as flowers or syrup) in places, such as France, where there are Senegalese immigrant communities.[57] The green leaves are used like a spicy version of spinach. They give flavour to the Senegalese fish and rice dish thieboudienne. Proper records are not kept, but the Senegalese government estimates national production and consumption at 700 t (770 short tons) per year.[58] In Myanmar their green leaves are the main ingredient in chin baung kyaw curry.[59]

Brazilians attribute stomachic, emollient, and resolutive properties to the bitter roots.[60]

Medical

[edit]Herbal medicine (high blood pressure)

[edit]A 2021 meta-analysis conducted by the Cochrane hypertension group concluded that currently the evidence is insufficient to establish if roselle, when compared to placebo, is effective in managing or lowering blood pressure in people with hypertension.[61] An older meta-survey (2015) in the Journal of Hypertension suggests a typical reduction in blood pressure of around 7.5/3.5 units (systolic/diastolic).[62] Both cite the need for additional well designed studies.[61][62]

Production

[edit]

China and Thailand are the largest producers and control much of the world supply.[63] The world's best roselle comes from Sudan and Nigeria, b. Mexico, Egypt, Senegal, Tanzania, Mali and Jamaica are also important suppliers but production is mostly used domestically.[64]

In the Indian subcontinent (especially in the Ganges Delta region), roselle is cultivated for vegetable fibres. Roselle is called meśta (or meshta, the ś indicating an sh sound) in the region. Most of its fibres are locally consumed. However, the fibre (as well as cuttings or butts) from the roselle plant has great demand in natural fibre using industries.

Roselle is a relatively new crop to create an industry in Malaysia. It was introduced in the early 1990s and its commercial planting was first promoted in 1993 by the Department of Agriculture in Terengganu. The planted acreage was 12.8 ha (30 acres) in 1993 and steadily increased to peak at 506 ha (1,000 acres) by 2000. The planted area is now less than 150 ha (400 acres) annually, planted with two main varieties.[citation needed] Terengganu state used to be the first and the largest producer, but now the production has spread more to other states. Despite the dwindling hectarage over the past decade or so, roselle is becoming increasingly known to the general population as an important pro-health drink. To a small extent, the calyces are also processed into sweet pickle, jelly and jam.

Cultivation

[edit]In the initial years, limited research work was conducted by University Malaya and Malaysian Agricultural Research and Development Institute (MARDI). Research work at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) was initiated in 1999.

Crop genetic resources and improvement

[edit]Genetic variation is important for plant breeders to increase crop productivity. Being an introduced species in Malaysia, there is a very limited number of germplasm accessions available for breeding.

UKM maintains a working germplasm collection and conducts agronomic research and crop improvement.

Mutation breeding

[edit]Conventional hybridization is difficult to carry out in roselle due to its cleistogamous nature of reproduction. Because of this, a mutation breeding programme was initiated to generate new genetic variability.[65] The use of induced mutations for its improvement was initiated in 1999 in cooperation with MINT (now called Malaysian Nuclear Agency) and has produced some promising breeding lines. Roselle is a tetraploid species; thus, segregating populations require longer time to achieve fixation as compared to diploid species. In April 2009, UKM launched three new varieties named UKMR-1, UKMR-2 and UKMR-3. These new varieties were developed using Arab as the parent variety in a mutation breeding programme which started in 2006.

Natural outcrossing under local conditions

[edit]A study was conducted to estimate the amount of outcrossing under local conditions in Malaysia. It was found that outcrossing occurred at a very low rate of about 0.02%. However, this rate is much lower in comparison to estimates of natural cross-pollination of between 0.20% and 0.68% as reported in Jamaica.

Gallery

[edit]-

A popular roselle variety planted in Malaysia: Terengganu. Roselle fruits are harvested fresh, and their calyces are made into a drink rich in vitamin C and anthocyanins.

-

Two varieties are planted in Malaysia — left Terengganu or UMKL-1, right Arab. The varieties produce about 8 t/ha (3.6 short tons/acre) of fresh fruits or 4 t/ha (1.8 short tons/acre) of fresh calyces. On the average, variety Arab yields more and has a higher calyx to capsule ratio.

-

Dried roselle calyces can be obtained in two ways. One way is to harvest the fruits fresh, decore them, and then dry the calyces; the other is to leave the fruits to dry on the plants to some extent, harvest the dried fruits, dry them further if necessary, and then separate the calyces from the capsules

-

Roselle calyces can be processed into sweet pickle. This is usually produced as a by-product of juice production. However, quality sweet pickle may require a special production process.

-

Variation in flower colour of roselle (a tetraploid species)

-

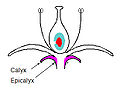

Calyx (a collective term for sepals of a flower); Epicalyx (a collective term for structures found on, below, or close to the true calyx, also called false calyx). Some varieties show pronounced epicalyx structures, such as found in variety Arab (plural calyces).

-

Decoring — removal of a seed capsule from the fruit using a simple hand-held gadget to obtain its calyx

-

Some breeding lines developed from the mutation breeding programme at UKM.

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "Roselle - plant". Encyclopedia Britannica. Revised and updated by Melissa Petruzzello. Archived from the original on 2022-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Abdoh, O. L. (1929). The Medical botanical vocabulary from Arabic into English, French and Latin (in Arabic). p. 27.

- ^ Lu Zoe (San Lwin) (1996). Myanmar proverbs. Illustrated by Thant Zin. Yan Gon: Myan Com Services. p. 34.

Lives in a plank-walled house but subsists on roselle leaves. / နေတော့ပျဉ်ထောင် စားတော့ချဉ်ပေါင်

- ^ Alhilali(特約著者), Bilal; 林珮琦(主編) (2020-12-01). Illustrated Middle East Arabic 圖解中東阿拉伯文(中英對譯) (in Arabic). SOW Publishing Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-988-15733-0-8.

- ^ Social forestry (in Thai). Sūn Wičhai Pāmai, Khana Wannasāt, Mahāwitthayālai Kasētsāt. 1992. p. 385.

- ^ Reinhorn, Marc, Dictionnaire laotien-français, Paris, CNRS, 1970, p. 688.

- ^ Pauline Dy Phon, វចនានុក្រមរុក្ខជាតិប្រើប្រាស់ក្នុងប្រទេសកម្ពុជា, Dictionnaire des Plantes utilisées au Cambodge, Dictionary of Plants used in Cambodia, ភ្នំពេញ Phnom Penh, បោះពុម្ពលើកទី ១, រោងពុម្ព ហ ធីម អូឡាំពិក (រក្សាសិទ្ធិ៖ អ្នកគ្រូ ឌី ផុន) គ.ស. ២០០០, ទំព័រ ៣៤៣-៣៤៤, 1st edition: 2000, Imprimerie Olympic Hor Thim (© Pauline Dy Phon), 1er tirage: 2000, Imprimerie Olympic Hor Thim, pp. 343-344; Mathieu LETI, HUL Sovanmoly, Jean-Gabriel FOUCHÉ, CHENG Sun Kaing & Bruno DAVID, Flore photographique du Cambodge, Toulouse, Éditions Privat, 2013, p. 360.

- ^ Mostafa, Capt Kawsar (2014-12-10). "Roselle /Chukur". Nature Study Society of Bangladesh. Archived from the original on 2023-01-19. Retrieved 2023-12-25.

- ^ a b c d e Kays, Stanley J. (2011-10-03). Cultivated vegetables of the world: a multilingual onomasticon. Springer. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-90-8686-720-2.

- ^ "Mathrubhumi - Agriculture - പുളിവെണ്ട വടക്കന് കേരളത്തിന്റെ സ്വന്തം വിള -". 2012-03-05. Archived from the original on 2012-03-05. Retrieved 2023-12-25.

- ^ "Rosella Growing Information". greenharvest.com.au. Archived from the original on 2023-03-04. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ^ McLay, Todd G.B. (2019-07-01). McLay, Todd G.B.; Kodela, P.G. (eds.). "Hibiscus sabdariffa". Flora of Australia. T.L. Lally. Canberra: Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. Archived from the original on 2023-09-21. Retrieved 2023-09-21.

- ^ Vercoe, Samara (2021-04-21). "Australia's own Rosella". Warndu. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ "Guide To The Aboriginal Garden Clayton Campus". Scribd. School of Biological Sciences, Monash University. 2010. p. 14. Retrieved 2024-01-07.

- ^ "Hibiscus heterophyllus". Australian Native Plants Society. Archived from the original on 2023-03-22. Retrieved 2023-09-20.

- ^ Leitner, Val; Cervone, Sarah; Gibson, Bhakti; Frank, Gabriel (2022-08-12). "Roselle - Florida Heritage Foods". Florida Heritage Foods. Santa Fe College. Archived from the original on 2023-04-08. Retrieved 2023-04-08.

- ^ Mu'azu, Mohammed Aminu (2012). Modern Tera dictionary : a practical dictionary of Tera with English and Hausa meanings : Tera-English-Hausa, English-Tera. Maimuna Adamu Magaji, [manufacturer not identified]. [Ghana]. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4776-4906-0. OCLC 806249070.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Balogun, Joseph Abiodun (2021). The Nigerian healthcare system : pathway to universal and high-quality health care. Cham, Switzerland. p. 243. ISBN 978-3-030-88863-3. OCLC 1294345200.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Abughidyer, Doosughun (May 2021). "Food Corner" (PDF). NIDCOM: Nigerians in Diaspora Commission. 11: 15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-07-13.

- ^ Benson, Dukuje (May 2015). "A survey on the genetic diversity of Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) germplasm in Nigeria" (PDF). Advances in Food Science and Technology. 3 (5): 318–320 – via International Scholars Journals.

- ^ Shruthi, V. H.; Ramachandra, C. T.; Nidoni, Udaykumar; Hiregoudar, Sharanagouda; Naik, Nagaraj; Kurubar, A. R. "Roselle (Hibiscus Sabdariffa L.) as a source of natural colour : a review" (PDF). Plant Archives. 16 (22): 515–522.

- ^ "Jus de bissap, bouy, ditax, gingembre-Spécifications". www.asn.sn. Association Sénégalaise de Normalisation. 2009. Archived from the original on 2023-04-09. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- ^ Tony Naden. "Birili2." Dagbani dictionary. Webonary. 2014. pp. 72–73.

- ^ Tony Naden. "Kananjuŋ." Dagbani dictionary. Webonary. 2014. p. 277.

- ^ Bofane, Koli Jean (2008). Mathématiques congolaises. pp. 162–163.

- ^ Bouquiaux, Luc; Kobozo, Jean-Marie; Diki-Kidiri, Marcel; Vallet, Jacqueline; Behaghel, Anne. 1978. Dictionnaire sango-français et lexique français-sango. Paris: Société des Etudes Linguistiques et Anthropologiques de France (SELAF). ISBN 2-85297-016-3.

- ^ ሙሳ አሮን. "ከርከዴ." ክብት-ቃላት ህግያ ትግሬ. አሕተምቲ ሕድሪ, 2005. p. 191. (in Tigrinya)

- ^ "Roselle - University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences". gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-09-21. Retrieved 2024-01-21.

- ^ The Routledge history of food. Carol Helstosky. London. 2015. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-415-62847-1. OCLC 881146219.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ortiz, Elisabeth Lambert (2007). 70 classic Mexican recipes : easy-to-make, authentic and delicious dishes, shown step-by-step in 250 sizzling colour photographs. London: Southwater. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-84476-434-1. OCLC 123375415.

- ^ Rousseau, Michelle (2018). Provisions : the roots of Caribbean cooking-- 150 vegetarian recipes. Suzanne Rousseau (1st ed.). New York, NY. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-7382-3467-0. OCLC 1023485526.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Groseille-pays". AZ Martinique (in French). Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ "Travel around Brazil: the discoveries of Ana Luiza Trajano in Maranhão - Instituto Brasil a Gosto". 2023-02-03. Archived from the original on 2023-02-03. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Cuxá Rice". Instituto Brasil a Gosto. 2020-11-12. Archived from the original on 2023-03-28. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Zhen J, Villani TS, Guo Y, Qi Y, Chin K, Pan MH, Ho CT, Simon JE, Wu Q (2016). "Phytochemistry, antioxidant capacity, total phenolic content and anti-inflammatory activity of Hibiscus sabdariffa leaves". Food Chemistry. 190: 673–680. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.06.006. PMID 26213025.

- ^ Bassey, Rosemary B. (28 August 2021). "The stain extracted from roselle is not daphniphylline". The Biological Stain Commission. Archived from the original on 2022-06-29.

- ^ Mohamed R, Fernández J, Pineda M, Aguilar M (2007). "Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) seed oil is a rich source of gamma-tocopherol". J Food Sci. 72 (3): S207–11. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00285.x. PMID 17995816.

- ^ Hansen, Barbara (7 October 1993). "Uncommon Herbs : In a Burmese Garden". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2012-07-07.

- ^ "Kelsa ~ Hau Za Cin :: ZOMI DAILY". www.zomidaily.org. 3 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2022-08-12.

- ^ "Chicken Tinola Recipe". Panlasang Pinoy. 9 November 2018. Archived from the original on 2021-05-15. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ Tanaka, Yoshitaka; Van Ke, Nguyen (2007). Edible Wild Plants of Vietnam: The Bountiful Garden. Thailand: Orchid Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-9745240896.

- ^ "Sorrel Juice Is Good for You". Sweet TnT Magazine. 8 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2020-05-16. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "Sorrel Drink". Simply Trini Cooking. 16 December 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-08-27.

- ^ Khanna, Sarah (29 February 2012). "Karkadeh: A Sweet Hibiscus Tea". Honest Cooking. Rosebud Media. Archived from the original on 2022-11-26.

- ^ Madubike, Flo. "Zobo Drink a.k.a. Zoborodo". All Nigerian Recipes. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08.

- ^ "Hibiscus Cooler". R.W. Knudsen Family. Knudsen & Sons, Inc. Archived from the original on 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ a b Adrian Miller (23 June 2015). "In Praise of Red Drink: The Origin Story Behind Soul Food's Most Iconic Beverage". First We Feast. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Grigsby Bates, Karen (16 June 2021). "A Taste Of Freedom : Code Switch". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2022-12-14. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ Mai_25759 (2012-09-07). "น้ำกระเจี๊ยบแดง มาฝากของเย็นเป็นเครื่องดื่มกันต่อค่ะ". Mthai Picpost. Archived from the original on 2013-08-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ King, Arno (2016-07-12). "Jam of the tropics: growing and using Rosella |". GardenDrum. Archived from the original on 2022-08-13. Retrieved 2021-09-09.

- ^ "Rosella Jam 120g". Bush Tucker Shop. Kurrajong Australian Native Foods. Archived from the original on 2014-03-29. Retrieved 2014-03-29.

- ^ Standley, Paul C.; Blake, S. F. (1923). "Trees and Shrubs of Mexico (Oxalidaceae-Turneraceae)". Contributions from the United States National Herbarium. 23 (3). Washington, D.C.: Department of Botany, Smithsonian Institution: 779. JSTOR 23492504.

- ^ Duke, James A. (7 January 1998). "Hibiscus sabdariffa L." Handbook of Energy Crops. Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Purdue University.

- ^ "Hibiscus". Drugs.com Herbal Database. Drugs.com. 21 May 2021. Archived from the original on 2022-01-19.

- ^ Peter, K.V (2007). Underutilized and Underexploited Horticultural Crops. Vol. 2. Kerala, India: New India Publishing Agency. p. 204. ISBN 978-8189422691.

- ^ Peter, K.V. (2007). Underutilized and Underexploited Horticultural Crops. Vol. 2. Kerala, India: New India Publishing Agency. p. 205. ISBN 978-8189422691.

- ^ Sula, Mike (4 September 2013). "How to eat hibiscus like the Burmese". Chicago Reader. Archived from the original on 2021-09-18.

- ^ Morton, Julia F. (1987). "Roselle: Hibiscus sabdariffa L." Purdue University, College of Agriculture. Archived from the original on 2000-06-01.

Morton, J. 1987. Roselle. p. 281–286. In: Fruits of warm climates. Julia F. Morton, Miami, FL.

- ^ a b Pattanittum, Porjai; Ngamjarus, Chetta; Buttramee, Fonthip; Somboonporn, Charoonsak (2021-11-27). "Roselle for hypertension in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD007894. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007894.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8626866. PMID 34837382.

- ^ a b Serban C, Sahebkar A, Ursoniu S, Andrica F, Banach M (2015). "Effect of sour tea (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) on arterial hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Hypertension. 33 (6): 1119–27. doi:10.1097/HJH.0000000000000585. PMID 25875025. S2CID 19042199.

- ^ Mazaud, François; Röttger, Alexandra; Steffel, Katja, eds. (2004-04-22). "HIBISCUS Post-harvest Operations page 4" (PDF). Prepared by Anne Plotto. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-12-11.

- ^ Mazaud, François; Röttger, Alexandra; Steffel, Katja; D'Aquilio, Larissa (eds.). "CHAPTER XXVIII HIBISCUS: Post-Production Management for Improved Market Access for Herbs and Spices - Hibiscus". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Prepared by Anne Plotto. Archived from the original on 2007-11-23. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ^ "FNCA 2005 WORKSHOP ON MUTATION BREEDING". Forum for Nuclear Cooperation in Asia (FNCA). 2005-12-06. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30.

Further reading

[edit]- Chau, J. W.; Jin, M. W.; Wea, L. L.; Chia, Y. C.; Fen, P. C.; Tsui, H. T. (2000). "Protective effect of Hibiscus anthocyanins against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced hepatic toxicity in rats". Food and Chemical Toxicology. 38 (5): 411–416. doi:10.1016/S0278-6915(00)00011-9. PMID 10762726.

- Mohamad, O.; Mohd. Nazir, B.; Abdul Rahman, M.; Herman, S. (December 2002). "Roselle: A new crop in Malaysia". Buletin Persatuan Genetik Malaysia. 8 (1): 12–13.

- Mohamad, O.; Mohd. Nazir, B.; Azhar, M.; Gandhi, R.; Shamsudin, S.; Arbayana, A.; Mohammad Feroz, K.; Liew, S.K.; Sam, C.W.; Nooreliza, C.E.; Herman, S. (2002). "Roselle improvement through conventional and mutation breeding". Proceedings of INC 2002. International Nuclear Conference 2002: Global Trends and Perspectives, Seminar I: Agriculture and Biosciences: 23–41. RN:34030224, TRN: MY0301988030224.

- Mohamad, O.; Ramadan, G.; Herman, S.; Halimaton Saadiah, O.; Noor Baiti, A. A.; Ahmad Bachtiar, B.; Aminah, A.; Mamot, S.; Jalifah, A.L. (2008). "A promising mutant line for roselle industry in Malaysia". FAO Plant Breeding News. 195.

- Pau, L. T.; Salmah, Y.; Suhaila, M. (2002). "Antioxidative properties of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) in linoleic acid model system". Nutrition & Food Science. 32 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1108/00346650210413951.

- Vaidya, K. R. (2000). "Natural cross-pollination in roselle, Hibiscus sabdariffa L. (Malvaceae)". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 23 (3): 667–669. doi:10.1590/S1415-47572000000300027.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of roselle at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of roselle at Wiktionary Media related to Roselle (plant) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Roselle (plant) at Wikimedia Commons- Roselle on Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Roselle". NewCROP, Center for New Crops & Plant Products. Purdue University.

- Stephens, James M. (2018). "Roselle — Hibiscus sabdariffa L." Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida. HS659.

- Jus de Bissap ("Roselle juice")