Hermann Höfle

Hermann Höfle | |

|---|---|

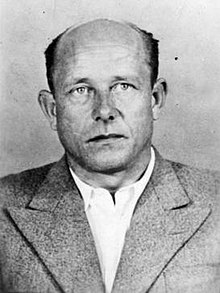

Höfle following his arrest in 1961 | |

| Birth name | Hermann Julius Höfle |

| Nickname(s) | Hans |

| Born | 19 June 1911 Salzburg, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | 21 August 1962 (aged 51) Vienna, Austria |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1933–1945 |

| Rank | Sturmbannführer (Major) |

| Commands | Second in command for Operation Reinhard |

| Awards | War Merit Cross 2nd Class With Swords |

| Other work | Auto mechanic |

Hermann Julius Höfle, also Hans (or) Hermann Hoefle (German: [ˈhɛʁman ˈhøːflə] ; 19 June 1911 – 21 August 1962[1]), was an Austrian-born SS commander and Holocaust perpetrator during the Nazi era. He was deputy to Odilo Globočnik in the Aktion Reinhard program, serving as his main deportation and extermination expert. Arrested in 1961 in connection with these crimes, Höfle died via suicide by hanging in prison before he was tried.

SS career

[edit]Born in Salzburg, Austria, Höfle joined the Nazi Party on 1 August 1933, with party number 307,469. He joined the SS at the same time. Before the war, he worked as an auto mechanic. Due to illegal political activities, he was imprisoned in Salzburg from 25 May 1935 to 1 January 1936.[1]

Crimes against humanity

[edit]After the conquest of Poland, Höfle served in Nowy Sącz, in Southern Poland. In November 1940 he served as an overseer of a Jewish labour camp southeast of Lublin. Up to December 1941 Höfle was in Mogilev. He was involved in deportations to the camps of Belzec, Sobibor, and Treblinka. He lived and worked from the Aktion Reinhard headquarters with the Julius Schreck Barracks, Ostland Strasse, in Lublin.

Höfle was "Coordinator" of Operation Reinhard and chief of staff to Odilo Globočnik, serving as his main deportation and extermination expert. Alongside Christian Wirth, Höfle had chief authority of Operation Reinhard beside Globočnik. At the beginning of the operation, he held the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer (captain). SS members, including those from Action T4 who were assigned to the operation, reported to the headquarters in Lublin and were instructed to their duties by Höfle. For an example of the limited paperwork, every member of Operation Reinhard signed the following declaration of secrecy:

I have been thoroughly informed and instructed by SS Hauptsturmführer Höfle, as Commander of the main department of Einsatz Reinhard of the SS and Police Leader in the District of Lublin:

1. that I may not under any circumstances pass on any form of information, verbally or in writing, on the progress, procedure or incidents in the evacuation of Jews to any person outside the circle of Einsatz Reinhard staff;

2. that the process of the evacuation of Jews is a subject that comes under "Secret Reich Document," in accordance with censorship regulation Vershl V. a;...

4. that there is an absolute prohibition on photography in the camps of Einsatz Reinhard;...

I am familiar with the above regulations and laws and am aware of the responsibilities imposed upon me by the task with which I have been entrusted. I promise to observe them to the best of my knowledge and conscience. I am aware that the obligation to maintain secrecy continues even after I have left the Service.

— From: Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka.[2]

As head of the "Main Department" (Hauptabteilung), Höfle was in charge of the organization and manpower of Operation Reinhard. He coordinated the deportations of Jews from all areas of the General Government and directed them to one of the extermination camps.[2] The deportation orders were coordinated and channeled through SS authorities from Höfle's office for the Lublin reservation, through the district SS and Police Leaders, down to the localities where the expulsions were to take place.

Around May 1942 in the General Government, a substitution policy developed for a short time in which Polish workers who were sent to the German Reich were gradually replaced with Jewish laborers. It became standard procedure to stop deportation trains from the Reich and Slovakia in Lublin in order to select able-bodied Jews for work in the General Government, the others being sent on to their deaths in Belzec. In this way, many Jews were temporarily spared death and instead relegated to forced labor. Höfle was one of the chief supporters and implementers of this policy.[3][4]

Höfle personally oversaw the deportation of the Warsaw Ghetto, the so-called Großaktion Warschau. The operation was preceded on 20 and 21 July 1942 by a spree of randomly killing actions along the streets of the Ghetto and by the arrest and brutal imprisonment of many others taken as hostages among counselors, department managers and those connected in a way or another to the Judenrat. All this was to intimidate and soften the Judenrat to the new upcoming measures. The day after, in the morning of 22 July, Sturmbannführer Höfle, accompanied by an entourage of SS and government officials, arrived at the Judenrat in the Warsaw Ghetto and announced to the chairman, Adam Czerniaków, that the Jews, regardless of sex or age and with but a few exceptions, were to be evacuated to the East. The exceptions were workers in German factories who had valid work permits, Judenrat employees, the Jewish Ghetto Police, hospital patients and employees, and the families of the exempt. The deportees were allowed to carry with them 15 kg of baggage, food for three days, money, gold, and other valuables. The order also called for 6,000 Jews to report to the Umschlagplatz every day by 4 p.m. to board the trains for deportation.[5]

Adam Czerniaków wrote in his diary on 22 July 1942, the day before he died by suicide:

Sturmbannführer Höfle (who is in charge of the evacuation) asked me into his office and informed me that for the time being my wife was free, but if the deportation were impeded in any way, she would be the first one to be shot as a hostage.

— From: Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka[6]

Höfle also played a key role in the Harvest Festival massacre of Jewish inmates of the various labour camps in the Lublin district in early November 1943. Approximately 43,000 Jews were murdered during this operation which was the single largest German massacre of Jews in the entire war. Höfle rejoined Globočnik in Trieste, after various missions in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Höfle Telegram

[edit]

On 11 January 1943, Höfle sent a radiogram from Lublin to SS-Obersturmbannführer Franz Heim in Kraków, who was at the time the deputy commander of the Security Police and SD in the General Government, and to SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann in Berlin. The message documented the total deportations of Jews to the four Operation Reinhard camps through 31 of December 1942. Today this document is called the Höfle Telegram.

After the war; arrest and suicide

[edit]On 31 May 1945 Höfle was found hiding in Möslacher Alm near the Weissensee Lake in Carinthia (Southern Austria) by the British, along with SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik and SS-Sturmbannführers Ernst Lerch and Georg Michalsen. After two years in the British interrogation center Wolfsberg (Carinthia), he was released to the Austrian judicial system. On 30 October 1947, under oath, he was released to continue his earlier occupation as an auto mechanic in his birthplace, Salzburg.

After an extradition request on 9 July 1948 by the Polish government, he fled to Italy, where he lived under a false name until 1951. Later he returned to Austria and then emigrated to West Germany. There he was employed briefly as an informant for U.S. Army Counterintelligence.

Höfle returned to Salzburg, where he lived as a free man until 2 January 1961, when he was arrested by the Austrian authorities and sent to prison in Vienna, where in 1962 he hanged himself before his trial could begin.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Klee 2003.

- ^ a b Arad 1987, pp. 18, 19.

- ^ Friedländer 2008, p. 347.

- ^ Browning 2000, p. 74.

- ^ Reich-Ranicki 2001, pp. 235–238.

- ^ Arad 1987, p. 61.

- ^ Reich-Ranicki 2001, p. 242.

Literature

[edit]- Arad, Yitzhak (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253113696. 1999 edition in Google book.

- Browning, Christopher R. (2000). "Chapter 3 - Jewish Workers in Poland: Self-Maintenance, Exploitation, Destruction". Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0521774901. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Friedländer, Saul (2008). The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945 (Reprinted ed.). New York City: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0060930486.

- Klee, Ernst (2003). Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945 [People Dictionary of the Third Reich. Who was what before and after 1945] (in German) (Second updated ed.). Frankfurt: S. Fischer. ISBN 978-3100393098.

- Reich-Ranicki, Marcel (January 2001). Mein Leben (in German) (2nd ed.). München (Germany): Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag. pp. 235–42. ISBN 3-423-12830-5.

- Peter Witte, Stephen Tyas: A New Document on the Deportation and Murder of Jews during "Einsatz Reinhardt" 1942. In: Holocaust and Genocide Studies 15 (2001), S. 468-486

- Josef Wulf: Das Dritte Reich und seine Vollstrecker. K. G. Saur Verlag KG, München 1978, ISBN 3-598-04603-0, S. 275-287

- 1911 births

- 1962 suicides

- 1962 deaths

- Austrian Waffen-SS personnel

- Austrian people who died in prison custody

- Military personnel from Salzburg

- Holocaust perpetrators in Poland

- Mechanics (people)

- Nazis who died by suicide in Austria

- Suicides by hanging in Austria

- Nazis who died by suicide in prison custody

- Operation Reinhard

- SS-Sturmbannführer

- Prisoners who died in Austrian detention

- World War II prisoners of war held by the United Kingdom

- People from the Duchy of Salzburg