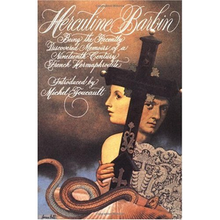

Herculine Barbin (memoir)

Cover | |

| Authors | Herculine Barbin Michel Foucault |

|---|---|

| Translator | Richard McDougall |

| Language | English, French |

| Publisher | Pantheon Books |

Publication date | June 12, 1980 |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 199 (Pantheon Books paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-0-394-73862-8 |

| OCLC | 5800446 |

| 616.69400924 | |

Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite is a 1980 English-language translation of Herculine Barbin's nineteenth-century memoirs, which were originally written in French. The book contains an introduction by Michel Foucault, which only appears in the English-language translation of the memoirs.[1] Foucault discovered Barbin's memoirs during his research about hermaphroditism for The History of Sexuality.[2]

Background

[edit]Herculine Barbin was an intersex woman born in 1838. Unlawfully in love with another woman,[3] she was forced to live as a man because of a judge's orders, after a doctor found her to be intersex, and her homosexual behaviors were brought forth.[4] Upon this legal change of her sex, Barbin's name was also changed, and she was referred as either Camille or Abel.[5] In 1868, Barbin committed suicide due to her poverty, gender and sexuality troubles and the false persona she was forced to maintain.[4]

Foucault explained in his introduction that the objective of social institutions was to restrict "the free choice of indeterminate individuals".[6] He noted that the legal efforts in the 1860s and 1870s to control gender identity occurred despite centuries of comparative acceptance of hermaphroditism.[7] During the Middle Ages, Foucault wrote, hermaphrodites were viewed as people who had an amalgamation of masculine and feminine traits. When they reached adulthood, hermaphrodites in the Middle Ages were allowed to decide whether they wanted to be male or female.[8] However, this procedure was abandoned in later times, when scientists decided that each person only had one real gender. When a person demonstrated the physical or mental traits of the opposite sex, such aberrations were deemed random or inconsequential.[8] Scholars Elizabeth A. Meese and Alice Parker noted that the memoir's lessons are applicable to the contemporary world in that the lack of a clear gender identity transgresses the truth.[9]

Responses

[edit]In his critical introduction, Foucault calls Barbin's pre-masculine upbringing a "happy limbo of non-identity" (xiii). Judith Butler, in their book Gender Trouble, takes this as an opportunity to read Foucault against himself, especially in History of Sexuality, Volume I. They call Foucault's introduction a "romanticized appropriation" of Barbin's experience; rather, Butler understands Barbin's upbringing not as an intersex body exposing and refuting the regulative strategies of sexual categorization (à la Foucault) but as an example of how the law maintains an "'outside' within itself". They argue that Barbin's sexual disposition—"one of ambivalence from the outset"—represents a recapitulation of the ambivalence inherent within the religious law that produces her. Specifically, Butler cites the "institutional injunction to pursue the love of the various 'sisters' and 'mothers' of the extended convent family and the absolute prohibition against carrying that love too far".

Intersex scholar Morgan Holmes states that Barbin's own writings showed that she saw herself as an "exceptional female", but female nonetheless.[10]

The collection of memoirs inspired Jeffrey Eugenides to write Middlesex. Believing that the memoir evaded discussion about intersex individuals' anatomy and emotions, Eugenides concluded that he would "write the story that I wasn't getting from the memoir".[11]

Commemoration

[edit]The birthday of Herculine Barbin is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance on 8 November.

References

[edit]- ^ Wilson 1996, p. 52

- ^ Brown, Frederick (1980-10-09). "The Heroic Hermaphrodite". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Meese & Parker 1989, p. 5

- ^ a b Daileader & Whalen 2010, p. 264

- ^ van den Wijngaard 1997, p. 3

- ^ Barbin & Foucault 1980, p. viii

- ^ Hart 1989, p. 279

- ^ a b Oksala 2005, pp. 115–116

- ^ Meese & Parker 1989, p. 6

- ^ Holmes, Morgan (July 2004). "Locating Third Sexes" (PDF). Transformations Journal. Regions of Sexuality (8). ISSN 1444-3775.

- ^ Goldstein, Bill (2003-01-01). "A Novelist Goes Far Afield but Winds Up Back Home Again". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barbin, Herculine; Foucault, Michel (1980). Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-73862-4.

- Daileader, Philip, ed. (2010). French Historians 1900-2000: New Historical Writing in Twentieth-Century France. Whalen, Philip. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-9867-7.

- Lynda, Hart (1989). Making a Spectacle: Feminist Essays on Contemporary Women's Theatre. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06389-8.

- Meese, Elizabeth A.; Parker, Alice (1989). The Difference Within: Feminism and Critical Theory. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 1-55619-042-5.

- Oksala, Johanna (2005). Foucault on Freedom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84779-6.

- Wilson, Emma (1996). Sexuality and the Reading Encounter: Identity and Desire in Proust, Duras, Tournier, and Cixous. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815885-8.

- van den Wijngaard, Marianne (1997). Reinventing the Sexes: The Biomedical Construction of Femininity and Masculinity. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33250-8.