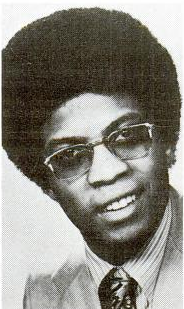

Herbie Hancock

Herbie Hancock | |

|---|---|

Hancock in 2023 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Herbert Jeffrey Hancock |

| Born | April 12, 1940 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Discography | Herbie Hancock discography |

| Years active | 1961–present |

| Labels | |

| Website | herbiehancock |

| Education | Grinnell College Roosevelt University Manhattan School of Music |

| Spouse |

Gigi Meixner (m. 1968) |

| Children | 1 |

Herbert Jeffrey Hancock (born April 12, 1940) is an American jazz musician, bandleader, and composer.[2] Hancock started his career with trumpeter Donald Byrd's group. He shortly thereafter joined the Miles Davis Quintet, where he helped to redefine the role of a jazz rhythm section and was one of the primary architects of the post-bop sound. In the 1970s, Hancock experimented with jazz fusion, funk, and electro styles, using a wide array of synthesizers and electronics. It was during this period that he released one of his best-known and most influential albums, Head Hunters.[3]

Hancock's best-known compositions include "Cantaloupe Island", "Watermelon Man", "Maiden Voyage", and "Chameleon", all of which are jazz standards. During the 1980s, he enjoyed a hit single with the electronic instrumental "Rockit", a collaboration with bassist/producer Bill Laswell. Hancock has won an Academy Award and 14 Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year for his 2007 Joni Mitchell tribute album River: The Joni Letters. In 2024, Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph ranked Hancock as the greatest keyboard player of all time.[4]

Since 2012, Hancock has served as a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, where he teaches at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.[5] He is also the chairman of the Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz[5] (known as the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz until 2019).

Early life

[edit]Hancock was born in Chicago, the son of Winnie Belle (née Griffin), a secretary, and Wayman Edward Hancock, a government meat inspector. His parents named him after the singer and actor Herb Jeffries.[6] He attended Hyde Park High School.[7] Like many jazz pianists, Hancock started with a classical education.[8] He started playing piano when he was seven years old, and his talent was recognized early. Considered a child prodigy,[9] he played the first movement of Mozart's Piano Concerto No. 26 in D Major, K. 537 (Coronation) at a young people's concert on February 5, 1952, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (led by CSO assistant conductor George Schick) at age 11.[10]

Throughout his teens, Hancock never had a jazz teacher; he developed his ear and sense of harmony by listening to the records of jazz pianists such as George Shearing, Erroll Garner, Bill Evans and Oscar Peterson. He was also influenced by records of the vocal group the Hi-Lo's. In his words:

By the time I actually heard the Hi-Lo's, I started picking that stuff out; my ear was happening. I could hear stuff and that's when I really learned some much farther-out voicings – like the harmonies I used on Speak Like a Child – just being able to do that. I really got that from Clare Fischer's arrangements for the Hi-Lo's. Clare Fischer was a major influence on my harmonic concept ... he and Bill Evans, and Ravel and Gil Evans, finally. You know, that's where it came from.[11]

In 1960, Hancock heard Chris Anderson play just once and begged him to accept him as a student.[12] Hancock often mentions Anderson as his harmonic guru.[13]

Hancock graduated from Grinnell College in 1960[14] with degrees in electrical engineering and music. Hancock then moved to Chicago,[14] and began working with Donald Byrd and Coleman Hawkins. During this time he also took courses at Roosevelt University.[15] Grinnell also awarded him an honorary Doctor of Fine Arts degree in 1972.[10][16] Byrd was attending the Manhattan School of Music in New York at the time and suggested that Hancock study composition with Vittorio Giannini (which he did for a short time in 1960). The pianist quickly earned a reputation, and played subsequent sessions with Oliver Nelson and Phil Woods.

Hancock recorded his first solo album, Takin' Off, for Blue Note Records in 1962. "Watermelon Man" (from Takin' Off) was to provide Mongo Santamaría with a hit single, but more importantly for Hancock, Takin' Off caught the attention of Miles Davis, who was at that time assembling a new band. Hancock was introduced to Davis by the young drummer Tony Williams, a member of the new band.

Career

[edit]Miles Davis Quintet (1963–1968) and Blue Note Records (1962–1969)

[edit]Hancock received considerable attention when, in May 1963,[10] he joined Davis's Second Great Quintet. Davis personally sought out Hancock, whom he saw as one of the most promising talents in jazz. The rhythm section Davis organized was young but effective, comprising bassist Ron Carter, 17-year-old drummer Williams, and Hancock on piano. After George Coleman and Sam Rivers each took a turn at the saxophone spot, the quintet gelled with Wayne Shorter on tenor saxophone. This quintet is often regarded as one of the finest jazz ensembles yet.[17]

While in Davis's band, Hancock also found time to record dozens of sessions for the Blue Note label, both under his own name and as a sideman with other musicians such as Wayne Shorter, Williams, Grant Green, Bobby Hutcherson, Rivers, Byrd, Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, and Eric Dolphy.

Hancock also recorded several less-well-known but still critically acclaimed albums with larger ensembles – My Point of View (1963), Speak Like a Child (1968) and The Prisoner (1969), albums which featured flugelhorn, alto flute and bass trombone in addition to the traditional jazz instrumentation. 1963's Inventions and Dimensions was an album of almost entirely improvised music, teaming Hancock with bassist Paul Chambers and two Latin percussionists, Willie Bobo and Osvaldo "Chihuahua" Martinez.

During this period, Hancock also composed the score to Michelangelo Antonioni's film Blowup (1966), the first of many film soundtracks he recorded in his career. As well as feature film soundtracks, Hancock recorded a number of musical themes used on American television commercials for such then-well-known products as Pillsbury's Space Food Sticks, Standard Oil, Tab diet cola, and Virginia Slims cigarettes. Hancock also wrote, arranged and conducted a spy type theme for a series of F. William Free commercials for Silva Thins cigarettes. Hancock liked it so much he wished to record it as a song but the ad agency would not let him. He rewrote the harmony, tempo and tone and recorded the piece as the track "He Who Lives in Fear" from his The Prisoner album of 1969.[18]

Davis had begun incorporating elements of rock and popular music into his recordings by the end of Hancock's tenure with the band. Despite some initial reluctance, Hancock began doubling on electric keyboards, including the Fender Rhodes electric piano at Davis's insistence. Hancock adapted quickly to the new instruments, which proved to be important in his future artistic endeavors.

Under the pretext that he had returned late from a honeymoon in Brazil, Hancock was dismissed from Davis's band.[19] In the summer of 1968 Hancock formed his own sextet. Although Davis soon disbanded his quintet to search for a new sound, Hancock, despite his departure from the working band, continued to appear on Davis records for the next few years. His appearances included In a Silent Way, A Tribute to Jack Johnson and On the Corner.

Fat Albert (1969) and Mwandishi era (1971–1973)

[edit]

Hancock left Blue Note in 1969, signing with Warner Bros. Records. In 1969, Hancock composed the soundtrack for Bill Cosby's animated prime-time television special Hey, Hey, Hey, It's Fat Albert.[20] Music from the soundtrack was later included on Fat Albert Rotunda (1969), an R&B-inspired album with strong jazz overtones. One of the jazzier songs on the record, the moody ballad "Tell Me a Bedtime Story", was later re-worked as a more electronic sounding song for the Quincy Jones album Sounds...and Stuff Like That!! (1978).

Hancock became fascinated with electronic musical instruments. Together with the profound influence of Davis's Bitches Brew (1970), this fascination culminated in a series of albums in which electronic instruments were coupled with acoustic instruments.

Hancock's first ventures into electronic music started with a sextet comprising Hancock, bassist Buster Williams and drummer Billy Hart, and a trio of horn players: Eddie Henderson (trumpet), Julian Priester (trombone), and multireedist Bennie Maupin. Patrick Gleeson was eventually added to the mix to play and program the synthesizers.

The sextet, later a septet with the addition of Gleeson, made three albums under Hancock's name: Mwandishi (1971), Crossings (1972) (both on Warner Bros. Records), and Sextant (1973) (released on Columbia Records); two more, Realization and Inside Out, were recorded under Henderson's name with essentially the same personnel. The music exhibited strong improvisational aspect beyond the confines of jazz mainstream and showed influence from the electronic music of contemporary classical composers.

Hancock's three records released in 1971–73 later became known as the "Mwandishi" albums, so-called after a Swahili name Hancock sometimes used during this era ("Mwandishi" is Swahili for "writer"). The first two, including Fat Albert Rotunda were made available on the 2-CD set Mwandishi: the Complete Warner Bros. Recordings, released in 1994. "Hornets" was later revised on the 2001 album Future2Future as "Virtual Hornets".

Among the instruments Hancock and Gleeson used were Fender Rhodes piano, ARP Odyssey, ARP 2600, ARP Pro Soloist Synthesizer, a Mellotron and the Moog synthesizer III.

From Head Hunters (1973) to Secrets (1976)

[edit]

Hancock formed the Headhunters, keeping only Maupin from the sextet and adding bassist Paul Jackson, percussionist Bill Summers, and drummer Harvey Mason. The album Head Hunters (1973) was a hit, crossing over to pop audiences but criticized within his jazz audience.[21] Stephen Erlewine, in a retrospective summary for AllMusic, said, "Head Hunters still sounds fresh and vital three decades after its initial release, and its genre-bending proved vastly influential on not only jazz, but funk, soul, and hip-hop."[22]

Drummer Mason was replaced by Mike Clark, and the band released a second album, Thrust, in 1974. (A live album from a Japan performance, consisting of compositions from those first two Head Hunters releases was released in 1975 as Flood). This was almost as well received as its predecessor, if not attaining the same level of commercial success. The Headhunters made another successful album called Survival of the Fittest in 1975 without Hancock, while Hancock himself started to make even more commercial albums, often featuring members of the band, but no longer billed as the Headhunters. The Headhunters reunited with Hancock in 1998 for Return of the Headhunters, and a version of the band (featuring Jackson and Clark) continues to play and record.

In 1973, Hancock composed his soundtrack to the controversial film The Spook Who Sat by the Door.[23] In the following year he composed the soundtrack to the first Death Wish film. One of his songs, "Joanna's Theme", was re-recorded in 1997 on his duet album with Shorter, 1+1.

Hancock's next jazz-funk albums of the 1970s were Man-Child (1975) and Secrets (1976), which point toward the more commercial direction Hancock would take over the next decade. These albums feature the members of the Headhunters band, but also a variety of other musicians in important roles.

From V.S.O.P. (1976) to Future Shock (1983)

[edit]

In 1978, Hancock recorded a duet with Chick Corea, who replaced him in the Davis band a decade earlier. Hancock also released a solo acoustic piano album, The Piano (1979), which was released only in Japan. (It was released in the US in 2004). Other Japan-only albums include Dedication (1974), V.S.O.P.'s Tempest in the Colosseum (1977), and Direct Step (1978). VSOP: Live Under the Sky was a VSOP album remastered for the US in 2004 and included a second concert from the tour in July 1979.

From 1978 to 1982, Hancock recorded many albums of jazz-inflected disco and pop music, beginning with Sunlight (featuring guest musicians including Williams and Pastorius on the last track) (1978). Singing through a vocoder, he earned a British hit,[24] "I Thought It Was You", although critics were unimpressed.[25] This led to more vocoder on his next album, Feets, Don't Fail Me Now (1979), which gave him another UK hit in "You Bet Your Love".[24]

Hancock toured with Williams and Carter in 1981, recording Herbie Hancock Trio, a five-track album released only in Japan. A month later, he recorded Quartet with trumpeter Wynton Marsalis, released in the US the following year. Hancock, Williams, and Carter toured internationally with Wynton Marsalis and his brother, saxophonist Branford Marsalis, in what was known as "VSOP II". This quintet can be heard on Wynton Marsalis's debut album on Columbia (1981). In 1984 VSOP II performed at the Playboy Jazz Festival as a sextet with Hancock, Williams, Carter, the Marsalis Brothers, and Bobby McFerrin.

In 1982, Hancock contributed to the album New Gold Dream (81,82,83,84) by Simple Minds, playing a synthesizer solo on the track "Hunter and the Hunted".

In 1983, Hancock had a pop hit with the Grammy Award-winning single "Rockit" from the album Future Shock. It was the first jazz hip-hop song[26][27][28] and became a worldwide anthem for breakdancers and for hip-hop in the 1980s.[29][30] It was the first mainstream single to feature scratching, and also featured an innovative animated music video, which was directed by Godley and Creme and showed several robot-like artworks by Jim Whiting. The video was a hit on MTV and reached No. 8 in the UK.[31] The video won in five categories at the inaugural MTV Video Music Awards. This single ushered in a collaboration with noted bassist and producer Bill Laswell. Hancock experimented with electronic music on a string of three LPs produced by Laswell: Future Shock (1983), the Grammy Award-winning Sound-System (1984), and Perfect Machine (1988).

During this period, he appeared onstage at the Grammy Awards with Stevie Wonder, Howard Jones, and Thomas Dolby, in a synthesizer jam. Lesser known works from the 1980s are the live album Jazz Africa (1987) and the studio album Village Life (1984), which were recorded with Gambian kora player Foday Musa Suso. In 1985, Hancock performed as a guest on the album So Red the Rose (1985) by the Duran Duran spinoff group Arcadia. He also provided introductory and closing comments for the PBS rebroadcast in the United States of the BBC educational series from the mid-1980s, Rockschool (not to be confused with the most recent Gene Simmons' Rock School series).

In 1986, Hancock performed and acted in the film Round Midnight. He also wrote the score/soundtrack, for which he won an Academy Award for Original Music Score. His film work was prolific during the 1980s, and included the scores to A Soldier's Story (1984), Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986), Action Jackson (1988 with Michael Kamen), Colors (1988), and the Eddie Murphy comedy Harlem Nights (1989). He would also write music for television commercials, with "Maiden Voyage" starting out as a cologne advertisement. At the end of the Perfect Machine tour, Hancock decided to leave Columbia Records after a 15-plus-year relationship.

1990s to 2000

[edit]

This departure resulted in a recording hiatus and several compilations during the first half of the 1990s.[32] Hancock resurfaced together with Carter, Williams, Shorter, and Davis admirer Wallace Roney to record A Tribute to Miles, which was released in 1994. The album contained two live recordings and studio recording songs, with Roney playing Davis's part as trumpet player. The album won a Grammy for best group album. Hancock also toured with Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland and Pat Metheny in 1990 on their Parallel Realities tour, which included a performance at the Montreux Jazz Festival in July 1990, and scored the 1991 comedy film Livin' Large, which starred Terrence C. Carson.

Hancock's next album, Dis Is da Drum, released in 1994, saw him return to acid jazz. Also in 1994, he appeared on the Red Hot Organization's compilation album Stolen Moments: Red Hot + Cool. The album, meant to raise awareness and funds in support of the AIDS epidemic in relation to the African-American community, was heralded as "Album of the Year" by Time magazine.

1995's The New Standard found Hancock and an all-star band including John Scofield, DeJohnette and Michael Brecker, interpreting pop songs by Nirvana, Stevie Wonder, the Beatles, Prince, Peter Gabriel and others.

A 1997 duet album with Shorter, 1+1, was successful; the song "Aung San Suu Kyi" winning the Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition. Hancock also achieved great success in 1998 with his album Gershwin's World, which featured readings of George and Ira Gershwin standards by Hancock and a plethora of guest stars, including Wonder, Joni Mitchell and Shorter. Hancock toured the world in support of Gershwin's World with a sextet that featured Cyro Baptista, Terri Lynne Carrington, Ira Coleman, Eli Degibri and Eddie Henderson.

2000 to 2009

[edit]In 2001, Hancock recorded Future2Future, which reunited Hancock with Laswell and featured doses of electronica as well as turntablist Rob Swift of the X-Ecutioners. Hancock later toured with the band, and released a concert DVD with a different lineup, which also included the "Rockit" music video. Also in 2001 Hancock partnered with Brecker and Roy Hargrove to record a live concert album saluting Davis and John Coltrane, Directions in Music: Live at Massey Hall, recorded live in Toronto. The threesome toured to support the album, and toured on-and-off through 2005.

The year 2005 saw the release of a duet album called Possibilities. It featured duets with Carlos Santana, Paul Simon, Annie Lennox, John Mayer, Christina Aguilera, Sting and others. In 2006, Possibilities was nominated for Grammy Awards in two categories: "A Song for You" (featuring Aguilera) was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance, and "Gelo No Montanha" (featuring Trey Anastasio on guitar) was nominated for a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Performance, although neither nomination resulted in an award.

Also in 2005, Hancock toured Europe with a new quartet that included Beninese guitarist Lionel Loueke, and explored textures ranging from ambient to straight jazz to African music. During the summer, Hancock re-staffed the Headhunters and went on tour with them, including a performance at the Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival. This lineup did not consist of any of the original Headhunters musicians. The group included Marcus Miller, Carrington, Loueke and Mayer. Hancock also served as the first artist in residence for Bonnaroo that summer.

In 2006, Sony BMG Music Entertainment (which bought out Hancock's old label, Columbia Records) released the two-disc retrospective The Essential Herbie Hancock. This set was the first compilation of his work at Warner Bros., Blue Note, Columbia and Verve/Polygram. This became Hancock's second major compilation of work since the 2002 Columbia-only The Herbie Hancock Box, which was released at first in a plastic 4 × 4 cube then re-released in 2004 in a long box set. Also in 2006, Hancock recorded a new song with Josh Groban and Eric Mouquet (co-founder of Deep Forest), "Machine", which featured on Groban's album Awake. Hancock also recorded and improvised with guitarist Loueke on Loueke's 1996 debut album Virgin Forest, on the ObliqSound label, resulting in two improvisational tracks – "Le Réveil des agneaux (The Awakening of the Lambs)" and "La Poursuite du lion (The Lion's Pursuit)".

Hancock, a longtime associate and friend of Joni Mitchell, released a 2007 album, River: The Joni Letters, that paid tribute to her work, with Norah Jones, Tina Turner and Corinne Bailey Rae adding vocals to the album.[33] Leonard Cohen contributed a spoken piece set to Hancock's piano. Mitchell herself also made an appearance. The album was released on September 25, 2007, simultaneously with the release of Mitchell's album Shine.[34] River won the 2008 Album of the Year Grammy Award. The album also won a Grammy for Best Contemporary Jazz Album, and the song "Both Sides Now" was nominated for Best Instrumental Jazz Solo, which made it only the second time in history that a jazz album won those two Grammy Awards.

On June 14, 2008, Hancock performed with others at Rhythm on the Vine at the South Coast Winery in Temecula, California, for Shriners Hospitals for Children. The event raised $515,000 for Shriners Hospital.[35]

On January 18, 2009, Hancock performed at the We Are One concert, marking the start of inaugural celebrations for American President Barack Obama.[36] Hancock also performed Rhapsody in Blue at the 2009 Classical BRIT Awards with classical pianist Lang Lang. Hancock was named as the Los Angeles Philharmonic's creative chair for jazz for 2010–12.[37]

2010 to present

[edit]

In June 2010, Hancock released The Imagine Project.

On June 5, 2010, Hancock received an Alumni Award from his alma mater Grinnell College.[38] On July 22, 2011, at a ceremony in Paris, he was named UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for the promotion of Intercultural Dialogue. In 2013, Hancock joined the University of California, Los Angeles faculty as a professor in the UCLA music department teaching jazz music.[39]

In a June 2010 interview with Michael Gallant of Keyboard magazine, Hancock talks about his Fazioli giving him inspiration to do things.[40]

On December 8, 2013, Hancock was given the Kennedy Center Honors Award for achievement in the performing arts. Terence Blanchard was the musical director and arranged Hancock compositions for performances with artists like Wayne Shorter, Joshua Redman, Vinnie Colaiuta, Lionel Loueke and Aaron Parks. Snoop Dogg performed a mash-up of the US3 arrangement of Hancock's "Cantaloupe Island" and his own "Gin and Juice". Mixmaster Mike from the Beastie Boys was featured on a rendition of Hancock's "Rockit".

Hancock appeared on the album You're Dead! by Flying Lotus, released in October 2014.

Hancock was the 2014 Charles Eliot Norton Professor of Poetry at Harvard University. Holders of the chair deliver a series of six lectures on poetry, "The Norton Lectures", poetry being "interpreted in the broadest sense, including all poetic expression in language, music, or fine arts". Previous Norton lecturers include musicians Leonard Bernstein, Igor Stravinsky and John Cage. Hancock's theme is "The Ethics of Jazz".[41]

Hancock's next album is being produced by Terrace Martin,[42] and will feature a broad variety of jazz and hip-hop artists including Wayne Shorter, Kendrick Lamar, Kamasi Washington, Thundercat, Flying Lotus, Lionel Loueke, Zakir Hussein and Snoop Dogg.[43]

On May 15, 2015, Hancock received an honorary doctor of humane letters degree from Washington University in St. Louis.[44]

On May 19, 2018, Hancock received an honorary degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.[45]

On June 26, 2022, Hancock performed at the Glastonbury Festival.[46][47]

Hancock was featured on the track "MOON" by the jazz duo Domi and JD Beck on their debut album NOT TiGHT, released July 29, 2022.

On February 4, 2023, Hancock performed at the Arise Fashion Week & Jazz Festival[48] at Eko Hotel, Lagos, Nigeria.

Personal life

[edit]Hancock has been married to Gigi Hancock (née Meixner) since 1968[1] and the couple have a daughter. In a 2019 interview, Hancock said: "Gigi is very compassionate. She really cares about other people. She spends most of her time helping her friends. She has a big heart. At the same time she won't let you get away with anything. If you try to sneak something past her, she'll call you on it in a second. She got me into the pop art scene in New York in the 1960s and I introduced her to my jazz world".[49]

In 1985, Hancock's sister, a lyricist who wrote for him and for Earth, Wind & Fire, was killed in the crash of Delta Air Lines Flight 191.[50]

In his memoir "Possibilities", written with Lisa Dickey and published in 2014, Hancock revealed he previously battled an addiction to crack cocaine in the 1990s and that his wife and daughter helped him get sober: "This was an intervention, and I was so embarrassed, but there was another feeling creeping in, too: relief. I had been struggling with this habit, and this secret, for so long. I looked at my daughter and sobbed, wondering how I had gotten to this place but thankful that it was finally going to end".[51]

Since 1972, Hancock has practiced Nichiren Buddhism as a member of the Buddhist association Soka Gakkai International.[52][53][54] As part of Hancock's spiritual practice, he recites the Buddhist chant Nam Myoho Renge Kyo each day.[55] In 2013, Hancock's dialogue with musician Wayne Shorter and Soka Gakkai International president Daisaku Ikeda on jazz, Buddhism and life was published in Japanese and English,[54] then in French.[56] In 2014, Hancock delivered a lecture at Harvard University titled "Buddhism and Creativity" as part of his Norton Lecture series.[57]

Cobra automobile ownership

[edit]In 1963, at the age of 23, Hancock purchased a new 1963 AC Shelby Cobra from a dealership in New York City for $6,000. He is still its owner and thus the longest owner of a Cobra. The car, serial number CSX2006, was the sixth Cobra ever produced, making it a rare and valuable vehicle. It is one of only 75 Cobras originally produced with a 260 cubic-inch engine and the only Cobra ever equipped with a two-barrel carburetor. The car has been estimated to be worth more than $2 million. Hancock plans to give the car to his grandson.[58][59][60]

Discography

[edit]

Studio albums

[edit]- Takin' Off (1962)

- My Point of View (1963)

- Inventions & Dimensions (1964)

- Empyrean Isles (1964)

- Maiden Voyage (1965)

- Speak Like a Child (1968)

- The Prisoner (1969)

- Fat Albert Rotunda (1969)

- Mwandishi (1971)

- Crossings (1972)

- Sextant (1973)

- Head Hunters (1973)

- Dedication (1974)

- Thrust (1974)

- Man-Child (1975)

- Secrets (1976)

- Third Plane (1977)

- Herbie Hancock Trio (1977)

- Sunlight (1978)

- Directstep (1979)

- The Piano (1979)

- Feets, Don't Fail Me Now (1979)

- Monster (1980)

- Mr. Hands (1980)

- Magic Windows (1981)

- Herbie Hancock Trio (1982)

- Quartet (1982)

- Lite Me Up (1982)

- Future Shock (1983)

- Sound-System (1984)

- Village Life (1985)

- Perfect Machine (1988)

- A Tribute to Miles (1994)

- Dis Is da Drum (1994)

- The New Standard (1996)

- 1+1 (1997)

- Gershwin's World (1998)

- Future 2 Future (2001)

- Possibilities (2005)

- River: The Joni Letters (2007)

- The Imagine Project (2010)

Filmography

[edit]| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Concrete Cowboys | Gideon | Episode: "The Wind Bags" |

| 1985 | The New Mike Hammer | Himself | Episode: "Firestorm" |

| 1986 | Round Midnight | Eddie Wayne | Also producer of the original motion pictures soundtrack |

| 1988 | Branford Marsalis Steep | Himself | |

| 1993 | Indecent Proposal | Himself | |

| 1995 | Invisible Universe | Poetry reader (voice) | Video game |

| 2002 | Hitters | District Attorney | |

| 2014 | Girl Meets World | Catfish Willie Slim | Episode: "Girl Meets Brother" |

| 2015 | Miles Ahead | Himself | |

| 2016 | River of Gold[61] | Narrator | Documentary |

| 2017 | Valerian and the City of a Thousand Planets | Defense Minister |

Concert films

[edit]- 2000: DeJohnette, Hancock, Holland and Metheny – Live in Concert

- 2002: Herbie Hancock Trio: Hurricane! with Ron Carter and Billy Cobham[62]

- 2002: The Jazz Channel Presents Herbie Hancock (BET on Jazz) with Cyro Baptista, Terri Lynne Carrington, Ira Coleman, Eli Degibri and Eddie Henderson (recorded in 2000)

- 2004: Herbie Hancock – Future2Future Live

- 2005: Herbie Hancock's Headhunters Watermelon Man (Live in Japan)

- 2006: Herbie Hancock – Possibilities with John Mayer, Christina Aguilera, Joss Stone, and more

Books

[edit]- Herbie Hancock: Possibilities (2014) ISBN 978-0-670-01471-2

- Reaching Beyond: Improvisations on Jazz, Buddhism, and a Joyful Life (2017) ISBN 978-1-938-25276-1

Awards

[edit]

Academy Awards

[edit]- 1986, Best Original Score, for Round Midnight

Grammy Awards

[edit]- 1984: Best R&B Instrumental Performance, for Rockit

- 1985: Best R&B Instrumental Performance, for Sound-System

- 1988: Best Instrumental Composition, for Call Sheet Blues

- 1995: Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Individual or Group, for A Tribute to Miles

- 1997: Best Instrumental Composition, for Manhattan (Island of Lights and Love)

- 1999: Best Instrumental Arrangement Accompanying Vocal(s), for St. Louis Blues

- 1999: Best Jazz Instrumental Performance, Individual or Group, for Gershwin's World

- 2003: Best Jazz Instrumental Album, Individual or Group, for Directions in Music at Massey Hall

- 2003: Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, for My Ship

- 2005: Best Jazz Instrumental Solo, for Speak Like a Child

- 2008: Album of the Year, for River: The Joni Letters

- 2008: Best Contemporary Jazz Album, for River: The Joni Letters

- 2011: Best Improvised Jazz Solo, for A Change Is Gonna Come

- 2011: Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals, for Imagine

Other awards

[edit]- Keyboard Readers' Poll: Best Jazz Pianist (1987, 1988); Keyboardist (1983, 1987)

- Playboy Music Poll: Best Jazz Group (1985), Best Jazz Album Rockit (1985), Best Jazz Keyboards (1985, 1986), Best R&B Instrumentalist (1987), Best Jazz Instrumentalist (1988)

- MTV Awards (5), Best Concept Video, "Rockit", 1983–'84

- Gold Note Jazz Awards – New York Chapter of the National Black MBA Association, 1985

- French Award Officer of the Order of Arts & Letters, 1985

- BMI Film Music Award, Round Midnight, 1986

- Honorary Doctorate of Music from Berklee College of Music, 1986 [63]

- U.S. Radio Award, Best Original Music Scoring – Thom McAnn Shoes, 1986

- Los Angeles Film Critics Association, Best Score – 'Round Midnight, 1986

- BMI Film Music Award, Colors, 1989

- Miles Davis Award, Montreal International Jazz Festival, 1997

- Soul Train Music Award, Best Jazz Album – The New Standard, 1997

- VH1's 100 Greatest Videos, "Rockit" is 10th Greatest Video, 2001

- NEA Jazz Masters Award, 2004

- Downbeat Readers' Poll Hall of Fame, 2005[64]

- Kennedy Center Honors, 2013

- Benjamin Franklin Medal (Royal Society of Arts), 2018

Memberships

[edit]- American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2013[65]

- Foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music.[66]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "A Literary Maiden Voyage: Herbie Hancock". Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock (American musician)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ Larson, Jeremy D. (April 5, 2020). "Herbie Hancock: Head Hunters Album Review". Pitchfork. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (October 16, 2024). "The 10 greatest keyboard players of all time – ranked". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved October 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "Herbie Hancock". The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- ^ Hancock, Herbie (February 2014). The Ethics of Jazz. YouTube. Mahindra Humanities Center. Event occurs at 11:50. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Obama to speak Friday at Hyde Park high school". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ Murph, John. "NPR's Jazz Profiles: Herbie Hancock". Npr.org. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Hentz, Stefan (August 3, 2010). "Herbie Hancock interview". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2012.

- ^ a b c Dobbins, Bill; Kernfeld, Barry (2001). "Herbie Hancock". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Coryell, Julie; Friedman, Laura (2000). Jazz-Rock Fusion, the people, the music. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 204. ISBN 0-7935-9941-5.

- ^ "CHRIS ANDERSON". Review of Love Locked Out. Mapleshade Music. Archived from the original on July 24, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "The Jazz Museum in Harlem". Jazzmuseuminharlem.org. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "Herbie Hancock '60". Grinnell College's Liberal Arts Club Band. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Herbie Hancock". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ^ The tune "Dr Honoris Causa" written by Joe Zawinul and performed by Cannonball Adderley's quintet is an ironic celebration of the honorary degree.

- ^ 50 great moments in jazz: How Miles Davis's second quintet changed jazz Archived November 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, theguardian.com

- ^ Hancock, Herbie & Dickey, Lisa Herbie Hancock: Possibilities Penguin, October 23, 2014

- ^ "Herbie Hancock: Too good to be true". The Independent. October 23, 2011.

- ^ "Hey, Hey, Hey, It's Fat Albert (TV Movie 1969)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- ^ Anton Spice (September 25, 2014). "Electric Herbie: 15 essential funk-era Herbie Hancock records". thevinylfactory.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2019.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2010). "Headhunters Herbie Hancock". Allmusic review of Headhunters. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock – The Spook Who Sat By The Door". discogs. February 21, 2017. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ a b Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums (19th ed.). London: Guinness World Records Limited. p. 242. ISBN 1-904994-10-5.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock". Warr.org. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Koskoff, Ellen (2005). Music Cultures in the United States: An Introduction. Psychology Press. pp. 364–. ISBN 978-0-415-96588-0. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ Price, Emmett George (2006). Hip Hop Culture. ABC-CLIO. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-85109-867-5. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ Keyes, Cheryl Lynette (2002). Rap Music and Street Consciousness. University of Illinois Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-0-252-07201-7. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ Hodgkinson, Will (May 10, 2004). "Culture quake: Rockit". Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ "Meet – Herbie Hancock". Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Tony; Kutner, Jon; Warwick, Neil (2002). The Complete Book of the British Charts (New & updated ed.). London: Omnibus. p. 447. ISBN 0711990751.

- ^ Smith, Montie (March 5, 1991). "The Collection review". Q Magazine. 55: 91.

- ^ Andre Mayer (June 18, 2007). "Key figure: An interview with jazz legend Herbie Hancock". CBC News. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- ^ "The Official Website of Joni Mitchell". Jonimitchell.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Shriners Hospitals for Children, "About Rhythm on the Vine" Archived December 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Rhythm on the Vine, 2008.

- ^ "Obama: People Who Love This Country Can Change It". Foxnews. January 18, 2009. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ^ Haga, E. Herbie Hancock Named L.A. Philharmonic's Next Creative Chair for Jazz Archived August 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Jazz Times, August 5, 2009.

- ^ Alumni Award: Herbert J. Hancock '60, archived from the original on June 9, 2010Hancock received an Alumni Award from Grinnell College at the annual Alumni Assembly June 5, 2010.

- ^ "Jazz legends Herbie Hancock, Wayne Shorter named UCLA professors" (Press release). University of California Office of Media Relations and Public Outreach. January 8, 2013. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Gallant, Michael (June 30, 2010). "Herbie Hancock The Master Keyboardist on the Culture-Bridging Power of Music". Keyboard. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ "Norton Lectures". Mahindra Humanities Center, Harvard University. February 4, 2014. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2014.

- ^ "Terrace Martin Talks New Jazz Supergroup, Producing for Herbie Hancock". Rolling Stone. May 15, 2017. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock's new album will feature Kendrick Lamar, Thundercat, Kamasi Washington, and Flying Lotus". Consequence of Sound. March 6, 2018. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock". Commencement. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ^ "Meet the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Class of 2018: An Overview of Commencement". RPI news. May 16, 2018. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- ^ "Glastonbury Sunday reviews: Herbie Hancock and DakhaBrakha". The Independent. June 26, 2022.

- ^ Swain, Marianka (June 26, 2022). "Glastonbury 2022 live: Diana Ross and Lorde perform ahead of Kendrick Lamar's headline act on Sunday". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ AriseNews (February 4, 2023). "Herbie Hancock, Wizkid Promise to Thrill on Final Day of ARISE Fashion Week & Jazz Festival". Arise News. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ Rocca, Jane (May 18, 2019). "Herbie Hancock: What I know about women". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ "Sister of musician dead in Delta crash". Austin American-Statesman. Associated Press. August 7, 1985. p. 1. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ Hancock, Herbie (October 24, 2014). "Herbie Hancock Reveals Crack-Addict Past in New Memoir". Billboard.com.

- ^ Reiss, Valerie. "Beliefnet Presents: Herbie Hancock on Buddhism, Buddhist, Jazz, Music". Beliefnet.com. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ Burk, Greg (February 24, 2008). "He's still full of surprises". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ a b "Hancock-Shorter-Ikeda Series on Jazz Published in Japanese | Daisaku Ikeda Website". Daisakuikeda.org. January 30, 2013. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ Reiss, Valerie. "Herbie, Fully Buddhist". Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2013.

- ^ "Parution de : Jazz, bouddhisme et joie de vivre; Échanges entre Herbie Hancock, Daisaku Ikeda & Wayne Shorter". acep france. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock named honorary Harvard professor, will deliver "Buddhism and Creativity" lecture". Lion's Roar. January 13, 2014. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Cotter, Tom (May 25, 2023). "Herbie Hancock has rocked an original Cobra longer than anyone". Hagerty Media. Archived from the original on May 29, 2023. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Ancil, Brandon (July 14, 2016). "A rude car salesman did me a huge favor, says jazz icon Herbie Hancock". CNBC. Archived from the original on July 14, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ Nelson, Chris (October 25, 2016). "Revisiting the Unbreakable Link Between Cars and Rock 'n' Roll". Motortrend. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "River of Gold". Riverofgoldfilm.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- ^ "VIEW DVD Listing". View.com. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved October 22, 2011.

- ^ "Herbie Hancock, Gary Burton to Help Berklee Celebrate Anniversary January 28 – Playbill". Playbill. January 2, 2006. Archived from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "Hancock named Harvard Foundation Artist of the Year", Harvard University Gazette, February 27, 2008 "Hancock named Harvard Foundation Artist of the Year — the Harvard University Gazette". Archived from the original on April 16, 2009. Retrieved February 28, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "American Academy of Arts and Sciences membership". Amacad.org. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ "Ledamöter". Kungl. Musikaliska Akademien (in Swedish). Retrieved November 12, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Herbie Hancock discography at Discogs

- Herbie Hancock at IMDb

- Herbie Hancock at TED

- Herbie Hancock interview about music and technology at AppleMatters

- Herbie Hancock Outside The Comfort Zone interview at JamBase

- Hancock Article by C.J Shearn on the New York Jazz Workshop blog, November 2014

- Herbie Hancock Interview at NAMM Oral History Collection (2006)

- Herbie Hancock on YouTube

- Herbie Hancock

- 1940 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American keyboardists

- 20th-century American male musicians

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- 20th-century American jazz composers

- 21st-century American keyboardists

- 21st-century American male musicians

- 21st-century American singer-songwriters

- 21st-century American jazz composers

- African-American Buddhists

- 21st-century African-American musicians

- 21st-century American Buddhists

- African-American film score composers

- African-American jazz composers

- African-American jazz pianists

- African-American male composers

- African-American male singers

- African-American songwriters

- American Buddhists

- American funk keyboardists

- American funk musicians

- American funk singers

- American jazz bandleaders

- American jazz keyboardists

- American jazz pianists

- American jazz singers

- American jazz songwriters

- American male jazz composers

- American male jazz pianists

- American male singer-songwriters

- American rhythm and blues keyboardists

- American rhythm and blues musicians

- American rhythm and blues singers

- American soul keyboardists

- American soul musicians

- American soul singers

- Avant-garde jazz musicians

- Best Original Music Score Academy Award winners

- Blue Note Records artists

- Columbia Records artists

- Converts to Sōka Gakkai

- DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members

- Grammy Award winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Grinnell College alumni

- Hard bop pianists

- Hyde Park Academy High School alumni

- Jazz-funk pianists

- Jazz fusion pianists

- Jazz musicians from Chicago

- Kennedy Center honorees

- Keytarists

- Manhattan School of Music alumni

- Members of Sōka Gakkai

- Miles Davis Quintet members

- Modal jazz pianists

- Nichiren Buddhists

- Post-bop pianists

- Rhythm and blues pianists

- Roosevelt University alumni

- Singers from Chicago

- Singer-songwriters from Illinois

- Soul-jazz keyboardists

- The Headhunters members

- UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music faculty

- Verve Records artists

- V.S.O.P. (group) members

- Warner Records artists

- Members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Music