Percy Fawcett

Percy Harrison Fawcett | |

|---|---|

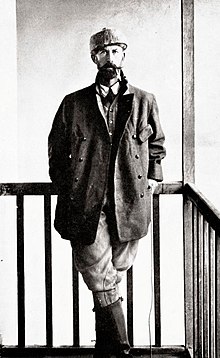

Fawcett in 1911 | |

| Born | Percy Harrison Fawcett 18 August 1867 |

| Disappeared | 29 May 1925 (aged 57) Mato Grosso, Brazil |

| Education | Newton Abbot Proprietary College |

| Occupation(s) | Artillery officer, archaeologist, geologist, explorer |

| Spouse |

Nina Agnes Paterson (m. 1901) |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Edward Douglas Fawcett (brother) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1886–1910 c.1914–1919 |

| Rank | Lieutenant-Colonel |

| Unit | Royal Artillery |

| Battles / wars | World War I |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Order 3 × Mentioned in despatches |

Percy Harrison Fawcett DSO (18 August 1867 – disappeared 29 May 1925) was a British geographer, artillery officer, cartographer, archaeologist and explorer of South America. He disappeared in 1925 (along with his eldest son, Jack, and one of Jack's friends, Raleigh Rimmel) during an expedition to find an ancient lost city which he and others believed existed in the Amazon rainforest.[1]

Life

[edit]Early life

[edit]Percy Fawcett was born on 18 August 1867 in Torquay, Devon, to Edward Boyd Fawcett and Myra Elizabeth (née MacDougall).[2] The Fawcetts were a family of old Yorkshire gentry (Fawcett of Scaleby Castle) who had prospered as shipping magnates in the East Indies during the late 18th and 19th centuries.[3] Fawcett's father had been born in India, and was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), while his elder brother, Edward Douglas Fawcett, was a mountain climber, Eastern occultist and the author of philosophical books and popular adventure novels.[4]

During the 1880s, Percy Fawcett was schooled at Newton Abbot Proprietary College, alongside Bertram Fletcher Robinson, the future sportsman, journalist, writer and mutual friend of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Thereafter, he attended the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and was commissioned as a lieutenant of the Royal Artillery on 24 July 1886. That same year, Fawcett met his future wife, Nina Agnes Paterson, whom he married in 1901 and had two sons, Jack (1903–1925?) and Brian (1906–1984), and one daughter, Joan (1910–2005).[5] On 13 January 1896, Fawcett was appointed Adjutant[6] of the 1st Cornwall (Duke of Cornwall's) Artillery Volunteers,[7] and was promoted to captain on 15 June 1897.[8] He later served in Hong Kong, Malta and Trincomalee, Ceylon.[9]

Fawcett joined the RGS in 1901 with the aim of studying surveying and mapmaking. Later, he worked for the British Secret Service in North Africa while pursuing the surveyor's craft. He served for the War Office on Spike Island in County Cork from 1903 to 1906, where he was promoted to major on 11 January 1905.[10] Fawcett became friends with authors Conan Doyle and Sir Henry Rider Haggard; the former used Fawcett's Amazonian field reports as inspiration for his novel The Lost World.[11]

Early expeditions

[edit]Fawcett's first expedition to South America was launched in 1906, after he RGS sent him to Brazil to map a jungle area at the border with Bolivia.[12] The RGS had been commissioned to map the area as a third party unbiased by local national interests. Fawcett arrived in La Paz in June. While on the expedition in 1907, he claimed to have seen and shot a 62-foot (19 m) long giant anaconda, a claim for which he was ridiculed by scientists. He reported other mysterious animals unknown to zoology, such as a small cat-like dog about the size of a foxhound, which he claimed to have seen twice, and the giant Apazauca spider, which was said to have poisoned a number of locals.[13][14] The giant peanuts which he found in the Mato Grosso region were almost certainly Arachis nambyquarae which has legumes up to 3.5 inches (nine cm) in length.[15]

Fawcett made seven expeditions between 1906 and 1924. He was mostly amicable with the local indigenous peoples through gifts, patience and courteous behaviour. In 1908 he traced the source of the Rio Verde (Brazil) and in 1910 made a journey to Heath River (on the border between Bolivia and Peru) to find its source, having retired from the British Army on 19 January. In 1911, Fawcett once again returned to the Amazon and charted hundreds of miles of unexplored jungle, accompanied by his trusted, longtime exploring companion, Henry Costin, and biologist and polar explorer James Murray. After a 1913 expedition, Fawcett supposedly claimed to have seen dogs with double noses. These may have been double-nosed Andean tiger hounds.[16]

Based on documentary research, Fawcett had by 1914 formulated ideas about a "lost city" he named "Z" (Zed) somewhere in the Mato Grosso.[17] He theorized that a complex civilization once existed in the region and that isolated ruins might have survived.[18] Fawcett also found a document known as Manuscript 512, written after explorations made in the sertão of the state of Bahia, and housed at the National Library in Rio de Janeiro. It is believed to have been authored by Portuguese bandeirante João da Silva Guimarães, who wrote that in 1753 he had discovered the ruins of an ancient city that contained arches, a statue and a temple with hieroglyphics; the city is described in great detail without providing a specific location. This city became a secondary destination for Fawcett, after "Z".

Fawcett carried with him in Brazil a jade statue of a human figure, with inscriptions on its chest and feet, that he claimed to have supernatural powers over the indigenous tribes of the Amazon. He told Ramiro Noronha, a Brazilian general, "by showing the statue, he could exercise an irresistible power over the natives."[19]

At the beginning of the First World War, Fawcett returned to Britain to serve with the British Army as a reserve officer in the Royal Artillery, volunteering for duty in Flanders and commanding an artillery brigade despite being nearly fifty years old. He was promoted from major to lieutenant-colonel on 1 March 1918,[20] and received three mentions in despatches from Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, in November 1916,[21] November 1917,[22] and November 1918.[23] He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Order in June 1917.[24]

After the war, Fawcett returned to Brazil to study local wildlife and archaeology. In 1920, he made a solo attempt to search for "Z" but ended it after suffering from a fever and shooting his pack animal.[18]

Final expedition

[edit]In 1924, with funding from a London-based group of financiers known as The Glove,[25] Fawcett returned to Brazil with his eldest son Jack and Jack's longtime friend, Raleigh Rimmel, for an exploratory expedition to find "Z". Fawcett left instructions stating that if the expedition did not return, no rescue expedition should be sent lest the rescuers suffer his fate.

Fawcett was a man with years of experience traveling and had taken equipment such as canned foods, powdered milk, guns, flares, a sextant and a chronometer. His travel companions were both chosen for their health, ability and loyalty to each other; Fawcett chose only two companions in order to travel lighter and with less notice to indigenous tribes, as some were hostile towards outsiders.[citation needed]

On 20 April 1925, Fawcett's final expedition departed from Cuiabá. In addition to Jack and Rimmel,[26] he was accompanied by two Brazilian laborers, two horses, eight mules and a pair of dogs. The last communication from the expedition was on 29 May when Fawcett wrote, in a letter to his wife delivered by a native runner, that he was ready to go into unexplored territory with only Jack and Rimmel. They were reported to be crossing the Upper Xingu, a southeastern tributary river of the Amazon River. The final letter, written from Dead Horse Camp, gave their location and was generally optimistic.[27]

In January 1927, the RGS declared and accepted the men as lost, close to two years after the party's last message. Soon after this declaration, there was an outpouring of volunteers to attempt to locate the lost explorers. Many expeditions attempting to find Fawcett failed. At least one lone searcher died in the attempt.

Many people assumed that local indigenous peoples killed Fawcett's party, as several tribes were nearby at the time: the Kalapalos, the last tribe to have seen them; the Arumás; the Suyás; and the Xavantes, whose territory they were entering. According to explorer John Hemming, Fawcett's party of three was too few to survive in the jungle and his expectation that his indigenous hosts would look after them was likely to have antagonized them by failing to bring any gifts to repay their generosity.[28]

Twenty years later, a Kalapalo chief called Comatzi told his people how unwelcome strangers were killed,[29] but others have thought they became lost and died of starvation,[29][30] and the bones provided by Comatzi turned out not to be those of Fawcett.[31] Edmar Morel and Nilo Vellozo reported that Comatzi's predecessor, Izarari, had told them he had killed Fawcett and his son Jack, seemingly by shooting them with arrows after Fawcett allegedly attacked him and other Indians when they refused to give him guides and porters to take him to their Chavante enemies. Rolf Blomberg reported that Izarari had told him that Rimmel had already died of fever in a Kurikuro camp.[32] A somewhat different version came from Orlando Villas-Bôas, who reported that Izarari had told him that he had killed all three men with his club the morning after Jack had allegedly consorted with one of his wives, when he claimed that Fawcett had slapped him in the face after the chief refused his demand for canoes and porters to continue his journey.[32]

The Kalapalo have an oral story of the arrival of three explorers which states that the three went east, and after five days the Kalapalo noticed that the group no longer made campfires. The Kalapalo say that a very violent tribe most likely killed them. However, both of the younger men were lame and ill when last seen, and there is no proof that they were murdered. It is plausible that they died of natural causes in the Brazilian jungle.[29][30][31]

In 1927, a nameplate of Fawcett's was found with an Indian tribe. In June 1933, a theodolite compass belonging to Fawcett was found near the Baciary Indians of Mato Grosso by Colonel Aniceto Botelho. However, the nameplate was from Fawcett's expedition five years earlier and had most likely been given as a gift to the chief of that tribe. The compass was proven to have been left behind before he entered the jungle on his final journey.[33][34][35]

Dead Horse Camp

[edit]Dead Horse Camp, or Fawcett's Camp, was his last known location.[36] From Dead Horse Camp, he wrote to his wife about the hardships that he and his companions had faced, his coordinates, his doubts in Rimmel, and Fawcett's plans for the near future. He concludes his message with, "You need have no fear of any failure..."[36]

One question remaining about Dead Horse Camp concerns a discrepancy in the coordinates Fawcett gave for its location. In the letter to his wife, he wrote: "Here we are at Dead Horse Camp, latitude 11 degrees 43' South and longitude 54 degrees 35' West, the spot where my horse died in 1920" (11°43′S 54°35′W / 11.717°S 54.583°W). However, in a report to the North American Newspaper Alliance he gave the coordinates as 13°43′S 54°35′W / 13.717°S 54.583°W.[37] The discrepancy may have been a typographical error. However, he may have intentionally concealed the location to prevent others from using his notes to find "Z".[38] It may have also been an attempt to dissuade any rescue attempts; Fawcett had stated that if he disappeared, no rescue party should be sent because the danger was too great.[37]

Posthumous controversy and speculations

[edit]Henry Costin's opinion

[edit]Explorer Henry Costin, who accompanied Fawcett on five of his previous expeditions, expressed his doubt that Fawcett would have perished at the hands of native indigenous people, as he typically enjoyed good relations with them. He believed that Fawcett had succumbed to either a lack of food or exhaustion.[30]

Rumours and unverified reports

[edit]During the ensuing decades, various groups mounted several rescue expeditions, without success. They heard only various rumours that could not be verified.

While a fictitious tale estimated that 100 would-be-rescuers died on several expeditions attempting to discover Fawcett's fate,[39] the actual toll was only one—a sole man who ventured after him alone.[40] One of the earliest expeditions was commanded by American explorer George Miller Dyott. In 1927, he claimed to have found evidence of Fawcett's death at the hands of the Aloique, but his story was unconvincing. From 1930 to 1931, Aloha Wanderwell used her seaplane to try to land on the Paraguay River to find him. After an emergency landing and living with the Bororo tribe for six weeks, Aloha and her husband Walter flew back to Brazil, with no luck.

Fawcett's alleged bones

[edit]In 1951, Orlando Villas-Bôas, activist for indigenous peoples, received what were claimed to be the actual remaining skeletal bones of Fawcett and had them analysed scientifically. The analysis supposedly confirmed the bones were Fawcett's, but his son Brian (1906–1984) refused to accept this. Villas-Bôas claimed that Brian was too interested in making money from books about his father's disappearance. Later scientific analysis confirmed that the bones were not Fawcett's.[41][31] As of 1965, the bones reportedly rested in a box in the flat of one of the Villas-Bôas brothers in São Paulo.[42]

In 1998, English explorer Benedict Allen went to talk to the Kalapalo people, said by Villas-Bôas to have confessed to having killed Fawcett and his party. An elder of the Kalapalo, Vajuvi, claimed during a filmed BBC interview with Allen that the bones found by Villas-Bôas were not really Fawcett's.[43][44] Vajuvi also denied that his tribe had any part in the disappearance of the expedition.[citation needed] No conclusive evidence supports the latter statement.[citation needed]

Villas-Bôas story

[edit]Danish explorer Arne Falk-Rønne journeyed to Mato Grosso during the 1960s. In a 1991 book, he wrote that he learned of Fawcett's fate from Villas-Bôas,[45] who had heard it from one of Fawcett's murderers. Allegedly, Fawcett and his companions had a mishap on the river and lost most of the gifts they had brought along for the Indian tribes. Continuing without gifts was a serious breach of protocol; since the expedition members were all more or less seriously ill at the time, the Kalapalo they encountered decided to kill them. The bodies of Jack and Rimmel were thrown into the river; Fawcett, considered an old man and therefore distinguished, received a proper burial. Falk-Rønne visited the Kalapalo and reported that one of the tribesmen confirmed Villas-Bôas's story about how and why Fawcett had been killed.

Fawcett's signet ring

[edit]In 1979, Fawcett's signet ring was found in a pawnshop. A new theory is that Fawcett and his companions were killed by bandits and the bodies were disposed of in a river while their belongings were despoiled.[46]

Russian documentary

[edit]In 2003, a Russian documentary film, The Curse of the Incas' Gold / Expedition of Percy Fawcett to the Amazon (Russian: Проклятье золота инков / Экспедиция Перси Фоссета в Амазонку), was released as a part of the television series Mysteries of the Century (Тайны века). Among other things, the film emphasizes the recent expedition of Oleg Aliyev to the presumed approximate place of Fawcett's last whereabouts and Aliyev's findings, impressions, and presumptions about Fawcett's fate. The film concludes that Fawcett may have been looking for the ruins of El Dorado, a city built by more advanced people from the other side of the Andes, and that the expedition members were killed by an unknown primitive tribe that had no contact with modern civilization.[47]

Commune in the jungle

[edit]On 21 March 2004, The Observer reported that television director Misha Williams, who had studied Fawcett's private papers, believed that he had not intended to return to Britain but rather meant to found a commune in the jungle, based on theosophical principles and the worship of his son Jack.[48] Williams explained his research in some detail in the preface to his play AmaZonia, first performed in April 2004.[49]

In popular culture

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

In 2005, The New Yorker staff writer David Grann visited the Kalapalo and reported that it had apparently preserved an oral history about Fawcett, among the first Europeans the tribe had ever seen. The oral account said that Fawcett and his party had stayed at their village and then left, heading eastward. The Kalapalos warned Fawcett and his companions that if they went that way they would be killed by the "fierce Indians" who occupied that territory, but Fawcett insisted upon going. The Kalapalos observed smoke from the expedition's campfire each evening for five days before it disappeared. The Kalapalos said they were sure the fierce natives had killed them.[18] The article also reports that a monumental civilisation known as Kuhikugu may have actually existed near where Fawcett was searching, as discovered recently by archaeologist Michael Heckenberger and others.[50] Grann's findings are further detailed in his book The Lost City of Z (2009).

In 2016, James Gray wrote and directed a film adaptation of Grann's book, with Charlie Hunnam starring as Fawcett.

In Charles MacLean's 1982 novel The Watcher, the protagonist believes himself to be a reincarnation of Percy Fawcett, and has visions of his supposed past life, experiencing a scene in the jungle seen through Fawcett's eyes.[51]

Episode 133 of British horror podcast The Magnus Archives features a fictional account given by Fawcett describing the events which occurred on his final expedition.

In 2022, Vox released a 6 minute and 54 second long short documentary film onto YouTube as part of their 'Atlas' video series investigating Fawcett's journeys in the Amazon, discussing his mistakes, and the reality of the 'Lost Cities' through modern technology.[52]

Works

[edit]- Fawcett, Percy and Brian Fawcett (1953), Exploration Fawcett, Phoenix Press (2001 reprint), ISBN 1-84212-468-4

- Fawcett, Percy and Brian Fawcett (1953), Lost Trails, Lost Cities, Funk & Wagnalls ASIN B0007DNCV4

- Fawcett, Brian (1958), Ruins in the Sky, Hutchinson of London

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Heckenberger, Michael J. (2009). "Lost Cities of the Amazon". Scientific American. 301 (4): 64–71. Bibcode:2009SciAm.301d..64H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1009-64 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 19780454. Archived from the original on 28 June 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "E. Douglas Fawcett (1866–1960)". Keverel Chess. 10 August 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012.

- ^ "🥇 ProtectedPool ➤ Most Powerful and Safest Web3 Smart DeFi Wallet 🔐".

- ^ "Fawcett, E Douglas". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. 18 January 2017.

- ^ "No. 25615". The London Gazette. 10 August 1886. p. 3855.

- ^ "No. 26703". The London Gazette. 24 January 1896. p. 424.

- ^ "No. 26705". The London Gazette. 31 January 1896. p. 589.

- ^ "No. 26869". The London Gazette. 2 July 1897. p. 3635.

- ^ Fawcett, Percy (4 May 2010). Exploration Fawcett: Journey to the Lost City of Z. The Overlook Press. ISBN 978-1590208366.

- ^ "No. 27792". The London Gazette. 12 May 1905. p. 3426.

- ^ "THE LOST CITY OF Z: A TALE OF DEADLY OBSESSION IN THE AMAZON," Kirkus Reviews. (Dec. 1, 2008): "The British explorer Percy Fawcett’s exploits in jungles and atop mountains inspired novels such as Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World".

- ^ "No. 27916". The London Gazette. 25 May 1906. p. 3657.

- ^ Fawcett, P. H. and Fawcett, B. Exploration Fawcett (1953)

- ^ "Apazauca spider". The Great Web of Percy Harrison Fawcett.

- ^ Flora Brasilica Volume 25 Part 2 page 17

- ^ "Double-nosed dog not to be sniffed at". BBC News. 10 August 2007.

- ^ "No. 28330". The London Gazette. 18 January 1910. p. 434.

- ^ a b c Grann, David (19 September 2005). "The Lost City of Z". The New Yorker. Retrieved 23 December 2016.

- ^ Antonio Callado, Esueleto na lagoa verde: Um ensaio sobre a vida e o sumico do Coronel Fawcett (Rio de Janeiro: Departamento de Impresa Nacional, 1953

- ^ "No. 31120". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 January 1919. p. 674.

- ^ "No. 29890". The London Gazette (Supplement). 2 January 1917. p. 208.

- ^ "No. 30421". The London Gazette (Supplement). 7 December 1917. p. 12912.

- ^ "No. 31077". The London Gazette (Supplement). 17 December 1918. p. 14926.

- ^ "No. 30111". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1917. pp. 5468–5470.

- ^ The London Illustrated News, 22 June 1924

- ^ "The epic of Percy Fawcett and the mysteries of the Serra del Roncador • Neperos". Neperos.com. 5 December 2023.

- ^ "Mr. Dyott's Expedition in Search of Colonel Fawcett". The Geographical Journal. 73 (6): 540–542. 1929. Bibcode:1929GeogJ..73..540.. doi:10.2307/1785337. ISSN 0016-7398. JSTOR 1785337.

- ^ John Hemming (1 April 2017). "The Lost City of Z is a very long way from a true story – and I should know". The Spectator. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

Everyone in Amazonia knew that you could not cut trails and keep your team fed with fewer than eight men. ... His other dictum was that Indians would look after them. This was equally dangerous. The Xingu tribes pride themselves on generosity, but they expect visitors to reciprocate. All expeditions in the past four decades had brought plenty of presents such as machetes, knives, and beads. Fawcett had none. He committed other blunders that antagonized their hosts. So it was only a matter of days before they were all dead.

- ^ a b c John Hemming (1 April 2017). "The Lost City of Z is a very long way from a true story – and I should know". The Spectator. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

Twenty years later, Chief Comatsi of the Kalapalo tribe gave a very detailed account of Fawcett's visit, reminding his assembled people of exactly how they had killed the unwelcome strangers. But the German anthropologist Max Schmidt, who was there in 1926, thought that they had plunged into the forests, got lost, and starved to death; this was also the view of a missionary couple called Young who were on another Xingu headwater. The Brazilian Indian Service regretted that Fawcett, who was obsessively secretive, had not asked for their help in dealing with the Indians. They felt he was killed because of the harshness and lack of tact that all recognised in him.

(Note: Hemming spells the chief's name 'Comatsi', but most other sources spell it 'Comatzi'.) - ^ a b c "Man Who Knew Fawcett". Lancashire Evening Post. 25 July 1931. p. 4. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ a b c "Izarari, Chief of the Kalapalos". The Great Web of Percy Harrison Fawcett. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

Comatzi, the later chief of Kalapalos after Izarari's death, was after much persuasion induced to disclose the grave of the murderer explorer, and bones were dug up and examined by a team of experts of the Royal Anthropological Institute in London, but the results indicated that those bones were not of Fawcett and there is a doubt whether they belong to a white man. The bodies of the younger ones were thrown in the river, said Comatzi. At all events, they have not been found.

- ^ a b "Reports for Fawcett's assassination by Izarari". The Great Web of Percy Harrison Fawcett. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

References for the summary & highlights of the following articles taken from: The Rolf Blomberg's book "Chavante, An expedition to the Tribes of the Mato Grosso", pages 70 & 71

(Blomberg's book was first published in 1958; various editions of it can be found here) - ^ Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Irving (1981). "History of the Search for Percy H. Fawcett, Part 2". Trivia-Library.com.

- ^ Cummins, Geraldine (March 1985). The Fate of Colonel Fawcett. Health Research Books. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-7873-0230-6.

- ^ Basso, Ellen B. (22 July 2010). The Last Cannibals: A South American Oral History. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-79206-7.

- ^ a b "Colonel Fawcett's Last Words". Colonel Percy Fawcett's Search For the Lost city of Z. Archived from the original on 28 September 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2011. Archived 28 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Dead Horse Camp (Fawcett's Camp)". The Great Web of Percy Harrison Fawcett. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "The Continuing Chronicles of Colonel Fawcett". Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Grann, David (2010). The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon. New York: Vintage Books. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4000-7845-5.

- ^ Hemming, John (1 April 2017). "The Lost City of Z is a very long way from a true story and I should know". The Spectator.

- ^ The upper jaw provides the clearest possible evidence that these human remains were not those of Colonel Fawcett, whose spare upper denture is fortunately available for comparison. Royal Anthropological Institute (London) (1951) "Report on the human remains from Brazil" as quoted by Grann (2009) p. 253

- ^ "1953 Col. Fawcett Peru Bolivia Brazil South America Lost Expedition El Dorado". eBay. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ Orcutt, Larry (2000). "Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett". Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2006. Archived 5 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Vajuvi said that they were the bones of his grandfather, Mugikia." Grann (2009) pp. 252–253

- ^ Falk-Rønne, Arne (16 March 2017). Dr. Klapperslange (in Danish). Lindhardt og Ringhof. ISBN 9788711714096.

- ^ witt, chie (6 April 2011). "Lost in the Amazon ~ About the Episode | Secrets of the Dead | PBS". Secrets of the Dead.

- ^ "Тайны века. Проклятие золота инков. Экспедиция Перси Фоссета в Амазонку" [Secrets of the century. The curse of the Inca gold. Expedition of Percy Fawcett to the Amazon.]. Filmix.net (in Russian). 2011. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ Thorpe, Vanessa (21 March 2004). "Veil lifts on jungle mystery of the Colonel who vanished". The Observer.

- ^ Williams, Misha. AmaZonia (PDF).

- ^ For further info see the last chapter of Grann's book The Lost City of Z and Charles Mann's book 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus.

- ^ "Percy Fawcett's Heart of Darkness". 17 April 2017.

- ^ How the "lost cities" of the Amazon were finally found, 7 July 2022, retrieved 21 September 2022

Bibliography

[edit]- Falk-Rønne, Arne. (1991). Klodens Forunderlige Mysterier. Roth Forlag.

- Fleming, Peter. (1933) Brazilian Adventure, Charles Scribner's Sons ISBN 0-87477-246-X

- Grann, David (2009) The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon ISBN 978-0-385-51353-1

- Leal, Hermes (1996), Enigma do Coronel Fawcett, o verdadeiro Indiana Jones (Colonel Fawcett: The Real-Life Indiana Jones; Published in Portuguese)

- La Gazette des Français du Paraguay, Percy Fawcett – Un monument de l'Exploration et de l'Aventure en Amérique Latine – Expédition du Rio Verde – bilingue français espagnol – numéro 6, Année 1, Asuncion Paraguay.

- Scriblerius, C.S. (2015), "Percyfaw Code, the secret dossier" Published by Amazon.com.

External links

[edit]- Forgotten Travellers: The Hunt for Colonel Fawcett Essay on Lt.-Col. Percy Harrison Fawcett

- Virtual Exploration Society – Colonel Percy Fawcett

- Colonel Fawcett

- Mad Dreams in the Amazon Essay on Fawcett from The New York Review of Books

- Lost in the Amazon: The Enigma of Col. Percy Fawcett PBS Secrets of the Dead documentary

- B. Fletcher Robinson & 'The Lost World' by Paul Spiring

- The Lost City of Z is a Long Way From a True Story and I Should Know by John Hemming in The Spectator

- Newspaper clippings about Percy Fawcett in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- 1867 births

- 1920s missing person cases

- 20th-century British archaeologists

- 20th-century British explorers

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Companions of the Distinguished Service Order

- English archaeologists

- English explorers

- Explorers of Amazonia

- Lost City of Z

- Lost explorers

- Military personnel from Torquay

- Missing person cases in Brazil

- Professor Challenger

- Royal Artillery officers