Political dissidence in the Empire of Japan

Political dissidence in the Empire of Japan covers individual Japanese dissidents against the policies of the Empire of Japan.

Dissidence in the Meiji and Taishō eras

[edit]High Treason Incident

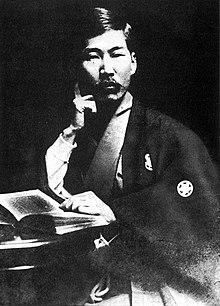

[edit]Shūsui Kōtoku, a Japanese anarchist, was critical of imperialism. He would write Imperialism: The Specter of the Twentieth Century in 1901.[1] In 1911, twelve people, including Kōtoku, were executed for their involvement in the High Treason Incident, a failed plot to assassinate Emperor Meiji.[2] Also executed for involvement with the plot was Kanno Suga, an anarcho-feminist and former common-law wife of Kōtoku.

Fumiko Kaneko and Park Yeol

[edit]Fumiko Kaneko was a Japanese anarchist who lived in Japanese-occupied Korea. She, along with a Korean anarchist, Park Yeol, were accused of attempting to procure bombs from a Korean independence group in Shanghai.[3] Both of them were charged with plotting to assassinate members of the Japanese imperial family.[4]

The Commoners' Newspaper

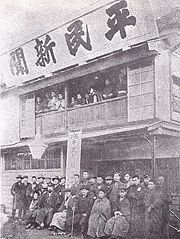

[edit]The Heimin Shimbun (Commoners' Newspaper) was a socialist newspaper which served as the leading anti-war vehicle during the Russo-Japanese War. It was a weekly mouthpiece of the socialist Heimin-sha (Society of Commoners). The chief writers were Kotoku Shusui and Sakai Toshihiko. When the Heimin decried the high taxes caused by the war, Sakai was sentenced to two months in jail. When the paper published The Communist Manifesto, Kotoku was given five months in prison, and the paper was shut down.[5]

Buddhist resistance

[edit]Although the state of Japanese Buddhism during this time was generally one of servility to the Japanese authoritarian system,[6] there were some exceptional individuals who resisted. Uchiyama Gudō was a Sōtō Zen Buddhist priest and anarcho-socialist. He was one of a few Buddhist leaders who spoke out against Japanese imperialism. Uchiyama was an outspoken advocate for redistributive land reform, overturning the Meiji emperor system, encouraging conscripts to desert en masse, and advancing democratic rights for all. He criticized Zen leaders who claimed that low social position was justified by karma and who sold abbotships to the highest bidder.[7]

After government persecution pushed the socialist and anti-war movements in Japan underground, Uchiyama visited Kōtoku Shūsui in Tokyo in 1908. He purchased equipment that would be used to set up a secret press in his temple. Uchiyama used the printing equipment to turn out popular socialist tracts and pamphlets, some of which were his own works.[8] Uchiyama was executed, along with Kotoku, for their involvement with the attempted assassination of Emperor Meiji.[9] Uchiyama's priesthood was revoked when he was convicted, but it was restored in 1993 by the Soto Zen sect.[10]

Another Soto Zen critic of Japanese imperialism and militarism was Inoue Shūten. He is known for advocating Buddhist pacifism and for criticizing D.T. Suzuki's stance of Buddhism and war.[11]

Among other notable individuals were the Zen masters Kōdō Sawaki, who expressed sentiments critical of war and its futility,[12] and Sawaki's student Taisen Deshimaru, who was jailed for aiding the resistance efforts of Bangka Islanders against Japanese colonialists.[13]

Attempted assassination of Hirohito

[edit]Daisuke Nanba, a Japanese student and communist, attempted to assassinate the Prince Regent Hirohito in 1924. Daisuke was outraged by the Kantō Massacre, a slaughter of Koreans and anarchists in the aftermath of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.[14] The dead included his partner, anarchist Sakae Ōsugi, feminist Noe Itō, and Ōsugi's six-year-old nephew, who were murdered by Masahiko Amakasu, the future head of the Manchukuo Film Association, a film production company based in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo. This event was known as the Amakasu incident.[15] Nanba was found guilty by the Supreme Court of Japan and hanged in November 1924.[16]

Osaka Incident

[edit]Hideko Fukuda was considered the "Joan of Arc" of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement in Japan during the 1880s.[17] She was also an editor of Sekai fujin (Women of the World), a socialist women's paper that Shūsui Kōtoku contributed articles to. In 1885, Fukuda was arrested for her involvement in the Osaka incident, a failed plan to supply explosives to Korean independence movements.

The Osaka Incident sought to overthrow the Meiji government via simultaneous open revolt in various parts of Japan.[18]: 232–233 Part of the plan also included assisting Korean independence activists in a coup against conservatives in the Korean monarchy.[18]: 232 Before the plan was able to be implemented, the police arrested the conspirators and confiscated the weapons before they could leave Japan for Korea.[19] Other participants in the plan included Oi Kentaro, another major figure of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement.[20] The outlaw brotherhood Gen'yōsha was also a major participant.[18]: 44

Liberal and moderate resistance

[edit]There were some critics of militarism among more mainstream socio-political circles, such as classical liberals and moderate conservatives. Saionji Kinmochi, who was the last of the genrō, an imperial advisor with progressive views, and a three-time prime minister, was known to be among the aristocrats who were most supportive of parliamentary government and often clashed with the military throughout his lengthy career, leading him to be considered as a potential assassination target leading up to the failed 1936 coup d'état.[21] Future Prime Minister and then-Foreign Minister Kijūrō Shidehara became known for his "Shidehara diplomacy" in the 1920s, favoring non-interventionism in China and warmer relations with the Anglo-American world.[22]

Japanese political refugees in early 20th century America

[edit]The American West Coast, which had a large Japanese population, was a haven for Japanese political dissidents in the early 20th century. Many were refugees from the "Freedom and People's Rights Movement." San Francisco, and Oakland in particular, were teeming with such people. In 1907, an open letter addressed to "Mutsuhito, Emperor of Japan from Anarchists-Terrorists" was posted at the Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco. As Mutsuhito was the personal name of Emperor Meiji, and it was considered rude to call the emperor by his personal name, this was quite an insult. The letter began with, "We demand the implementation of the principle of assassination." The letter also claimed that the emperor was not a god. The letter concluded with, "Hey you, miserable Mutsuhito. Bombs are all around you, about to explode. Farewell to you." This incident changed the Japanese government's attitude of leftist movements.

Early Shōwa era and the rise of militarism

[edit]

Ikuo Oyama

[edit]Ikuo Oyama was a member of the left-leaning Labour-Farmer Party, which advocated universal suffrage, minimum wages, and women's rights. Yamamoto Senji, a colleague of his, was assassinated on February 29, on the same day as he had presented testimony in the Diet regarding torture of prisoners. The Labour-Farmer Party was banned in 1928 due to accusations of having links to communism. Oyama fled Japan in 1933 to the United States as a result. He got a job at Northwestern University at its library and political science department. During his exile, he worked closely with the U.S. Government against the Empire of Japan. Oyama happily shook hands with Zhou Enlai, who fought the Japanese in the Second Sino-Japanese War. Oyama was given a Stalin Award prize on December 20, 1951. However, his colleagues begged him not to accept the award for fear that he would become a Soviet puppet. Some of his oldest friends abandoned him when he accepted it.[citation needed]

Modern girls

[edit]Modern girls (モダンガール, modan gāru) were Japanese women who adhered to Westernized fashions and lifestyles in the 1920s. They were the equivalent of America's flappers.[23]

This period was characterized by the emergence of young working-class women with access to consumer goods and the money to buy those consumer goods. Modern girls were depicted as living in cities, being financially and emotionally independent, choosing their own suitors, and being apathetic towards politics.[24] Thus, the modern girl was a symbol of Westernization. However, after a military coup in 1931, extreme Japanese nationalism and the Great Depression prompted a return to the 19th-century ideal of good wife, wise mother.

The Salon de thé François

[edit]

The Salon de thé François was a western-style café established in Kyoto on 1934 by Shoichi Tateno, who participated in labour movements, and anti-war movements.[25] The cafe was a secret source of funds for the then-banned Japanese Communist Party.[26] The anti-fascist newspaper Doyōbi was edited and distributed from the café.[27]

The Takigawa Incident

[edit]In March 1933, the Japanese parliament attempted to control various education groups and circles. The Interior Ministry banned two textbooks on criminal laws written by Takigawa Yukitoki of Kyoto Imperial University. The following month, Konishi Shigenao, president of Kyoto University, was requested to dismiss Professor Takigawa. Konishi rejected the request, but due to pressure from the military and nationalist groups, Takigawa was fired from the university. This led to all 39 faculty members of Kyoto Imperial University's law faculty resigning. Furthermore, students boycotted classes and communist sympathizers organized protests. The Ministry of Education was able to suppress the movement by firing Konishi. In addition to this attempt by the Japanese government to control educational institutions, during the term of the education minister, Ichirō Hatoyama, a number of elementary school teachers were also dismissed for having what were considered "dangerous thoughts".[28]

Soaring Mast

[edit]Following the outbreak of the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria, the Japanese Communist Party had infiltrated the military, including in Tokyo, and Osaka. They would distribute leaflets, and newspapers opposing the war.[29] Sakaguchi Kiichiro, a Japanese Communist sailor, founded the anti-war "The Soaring Mast" along with other anti-sailors. Six issues were produced and distributed.[30] Sakaguchi Kiichiro had enlisted in the Imperial Japanese Navy following his graduation from High School. During his service, he joined the Japanese Communist Party.[31] Saakaguchi Kiichiro would be arrested in a Police raid in Tokyo. He was tortured in Hiroshima Prison by the Special Higher police. He would die in prison on 1933.[32]

Dissidence during World War II

[edit]Japanese working with the Chinese resistance

[edit]

Kaji Wataru was a Japanese proletarian writer who lived in Shanghai. His wife, Yuki Ikeda, suffered through torture at the hands of the Imperial Japanese. She fled Japan when she was very young, working as a ballroom dancer in Shanghai to earn a living. They were friends with Chinese cultural leader Guo Moruo. Kaji and Yuki would escape Shanghai when the Japanese invaded the city. Kaji, along with his wife, were involved with the re-education of captured Japanese soldiers for the Kuomintang in Chongqing during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[33]

His relationship with Chiang Kai-shek was troubled due to Chiang Kai-shek's anti-communism.[34] Kaji would work with the Office of Strategic Services in the later stages of the war.[35]

Sanzō Nosaka, a founder of the Japanese Communist Party, worked with the Chinese Communists in Yan'an during the Second Sino-Japanese war. He was in charge of the re-education of captured Japanese troops. Japanese Intelligence in China were desperate to eliminate him, but they always failed in their attempts. Sanzo went by the name "Susumu Okano" during the war.[36] Today, Sanzō Nosaka is considered a disgraced figure to the Japanese Communist Party, when it was discovered that he falsely accused Kenzō Yamamoto, a Japanese communist, of spying for Japan.[37] Joseph Stalin executed Yamamoto in 1939.[38]

Sato Takeo was a Japanese doctor who was a member of Norman Bethune's medical team in the Second-Sino Japanese War. Norman's team was responsible for giving medical care to soldiers of the Chinese Eighth Route Army.[39]

Japanese working with the United States

[edit]Taro Yashima (real name Jun Atsushi Iwamatsu), an artist, joined a group of progressive artists, sympathetic to the struggles of ordinary workers and opposed to the rise of Japanese militarism in the early 1930s. The antimilitarist movement in Japan was highly active at the time, with posters protesting the Japanese aggression in China being widespread.[40] Following the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, however, the Japanese government began heavy handed suppression of domestic dissent including the use of arrests and torture by the Tokkō (special higher police).[40] Iwamatsu who was thrown into a Japanese prison without trial along with his pregnant wife, Tomoe Sasako, for protesting militarism in Japan. Conditions in the prison were deplorable and the two were subjected to inhumane treatment including beatings. The authorities demanded false confessions, and those who gave them were set free.[40]

Iwamatsu and Sasako came to America using student visas to study art in 1939, leaving behind their son, Makoto Iwamatsu, who would grow up to be a prolific actor in America, with relatives. When WWII broke out, Iwamatsu joined the Office of Strategic Services as a painter. He would adopt the pseudonym Taro Yashima, to protect his son who was still in Japan. Iwamatsu would continue to use his pseudonym when he wrote children's books, such as Crow Boy, after the war.[41]

Eitaro Ishigaki was an issei painter who immigrated to America from Taiji, Wakayama, in Japan. At the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Pacific War, he painted anti-war, and anti-fascist artwork.[42] His painting Man on the Horse (1932) depicted a plain-clothed Chinese guerrilla confronting the Japanese army, heavily equipped with airplanes and warships. It became the cover of New Masses, an American communist journal. Flight (1937) was a painting that depicted two Chinese women escaping Japanese bombing, running with three children past one man lying dead on the ground.[43] During the war, he worked for the United States Office of War Information along with his wife, Ayako.[44]

Yasuo Kuniyoshi was an issei (first-generation Japanese immigrant) anti-fascist painter based in New York. In 1942, he raised funds for the United China Relief to provide humanitarian aid to China when it was still at war with Japan.[45] Time magazine ran an article featuring Yasuo Kuniyoshi, George Grosz, a German anti-Nazi painter, and Jon Corbino, an Italian painter, standing behind large unflattering caricatures of Hirohito, Hitler, and Mussolini.[46] Yasuo Kuniyoshi showed opposition to Tsuguharu Foujita's art show at the Kennedy Galleries. During WWII, Tsuguharu Foujita painted propaganda artwork for the Empire of Japan. Yasuo called Foujita a fascist, an imperialist, and an expansionist.[47] Yasuo Kuniyoshi would work for the Office of War Information during WWII, creating artwork that depicted atrocities committed by the Empire of Japan, even though he was himself labeled an "enemy alien" in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor.[48]

Japanese working with the British

[edit]Shigeki Oka was an issei socialist and journalist for the Yorozu Chōhō, and a friend of Kōtoku Shūsui or Toshihiko Sakai. Oka would welcome Kotoku when he arrived in Oakland.[49] He was a member of the Sekai Rodo Domeikai (World Labour League).[50] In 1943, the British Army hired Shigeki Oka to print propaganda materials in Kolkata in India, such as the Gunjin Shimbun (Soldier Newspaper).[51]

The SOAS, University of London was used by the British Army to train soldiers in Japanese. The teachers were usually Japanese citizens who had stayed in Britain during the war, as well as Canadian Nisei. When Bletchley Park, Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), was concerned about the slow pace of the SOAS, started their own Japanese language courses in Bedford in February 1942. The courses were directed by Royal Army cryptographer, Col. John Tiltman, and retired Royal Navy officer, Captain. Oswald Tuck.[52]

Sorge spy ring

[edit]

Richard Sorge was a Soviet military intelligence officer who conducted surveillance in both Germany and Japan, working under the identity of a Japanese correspondent for the German newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung. He arrived in Yokohama in 1933 and recruited two journalists: Asahi Shimbun journalist Hotsumi Ozaki, who wanted successful communist revolutions in both China and Japan;[53] and Yotoku Miyagi in 1932 who translated Japanese newspaper articles and reports into English and created a diverse network of informants.

In 1941, he relayed to the Soviet Union that Prime minister Konoe Fumimaro had decided against an immediate attack on the Soviets, choosing instead to keep forces in French Indochina (Vietnam). This information allowed the Soviet Union to reallocate tanks and troops to the western front without fear of Japanese attacks. Later that year, both Sorge and Ozaki were found guilty of treason (espionage) and were executed three years later in 1944.[54]

Pacifist resistance

[edit]

Pacifism was one of the many ideologies targeted by the Tokko. George Ohsawa, a pacifist and the founder of the macrobiotic diet, was thrown in jail for his anti-war activities in January 1945. While in prison, he suffered through harsh treatment. When he was finally released, one month after the bombing of Hiroshima, he was gaunt, crippled, and 80% blind.[55] Toyohiko Kagawa, a Christian pacifist, was arrested in 1940 for apologizing to the Republic of China for Japan's occupation of China.[56] Yanaihara Tadao, another Christian, circulated an anti-war magazine beginning in 1936 and through the end of the war.

Anti-fascist bulletins

[edit]The journalist Kiryū Yūyū published an anti-fascist bulletin, Tazan no ishi, but it was heavily censored and ceased publication with Kiryū's death at the end of 1941.

A lawyer named Masaki Hiroshi had more success with his independent bulletin called Chikaki yori. Masaki's main technique against the censors was simply masking his critiques of the government in thinly veiled sarcasm. This was apparently unnoticed by the censors, and he was able to continue publishing fierce attacks on the government through the end of the war. His magazine had many intellectual readers such as Hasegawa Nyozekan, Hyakken Uchida, Rash Behari Bose and Saneatsu Mushanokōji. After the war, Masaki became an idiosyncratic defense lawyer, successfully forcing many recognitions of police malpractice at great risk to his life.

A lesser known bulletin was Kojin konjin, a monthly critique of the army published by the humorist Ubukata Toshirō. Again, the use of satire without explicit call to political action allowed Ubukata to avoid prosecution through the end of the war, although two issues were banned. He ceased publication in 1968.[57]

A Diary of Darkness

[edit]Kiyosawa Kiyoshi was an American-educated commentator on politics and foreign affairs who lived in a time when Japanese militarists rose to power. He wrote a diary as notes for a history of the war, but it soon became a refuge for him to criticize the Japanese government, and to express opinions he had to repress publicly. It chronicles growing bureaucratic control over everything from the press to people's clothing. Kiyosawa showed scorn towards Tojo and Koiso, lamenting the rise of hysterical propaganda, and related his own and his friends' struggles to avoid arrest. He also recorded the increasing poverty, crime, and disorder, tracing the gradual disintegration of Japan's war effort and the looming certainty of defeat. His diary was published under the name A Diary of Darkness: The Wartime Diary of Kiyosawa Kiyoshi, in 1948. It is today regarded as a classic.[58]

Antiwar film

[edit]Fumio Kamei was arrested under the Peace Preservation Law after releasing two state-funded documentaries that, while purporting to be celebrations of Japan and its army, portrayed civilian victims of Japanese war crimes and mocked the "sacred war" message and "beautiful Japan" propaganda. He was released after the war and continued to make anti-establishment films.

Nisei involvement in Japanese resistance

[edit]Karl Yoneda was a nisei (second-generation Japanese immigrant) born in Glendale, California. Before World War II, he went to Japan to protest the Japanese invasion of China with Japanese militants. Toward the end of 1938 he was involved with protests of war cargo heading to Japan along with Chinese and Japanese militants.[59] He would join the United States Military Intelligence Service in the war.[60]

Koji Ariyoshi was a nisei sergeant in the U.S. Army during WWII, and an opponent of Japanese militarism. He was a member of the United States Dixie Mission, where he met Sanzo Nosaka and Mao Zedong.[61] During the war, he also met with Kaji Wataru in Chongqing, hearing about him when he was in Burma.[62] Koji Ariyoshi would form the Hawaii-China People's Friendship Association in 1972.[63]

Sōka Kyōiku Gakkai resistance

[edit]Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, founder of the japanese controversial Soka Gakkai organization, is sometimes considered as a political dissident.[64]: 14–15

As the war progressed, the Japanese government ordered that a shinto talisman (object of devotion) should be placed in every home and temple. Makiguchi and the Soka Gakkai leadership openly refused. Makiguchi, his disciple Josei Toda, and 19 other leaders of the Soka Kyoiku Gakkai (Value Creating Education Society) were arrested on July 6, 1943, on charges of breaking the Peace Preservation Law and lèse-majesté: for "denying the Emperor's divinity" and "slandering" the Ise Grand Shrine.

On November 18, 1944, Makiguchi died of malnutrition in prison, at the age of 73.

Conservative, centrist, and classical liberal resistance

[edit]Saitō Takao caused a stir in his time for delivering a fiery speech against the Sino-Japanese War, leading to his expulsion from the Diet.[65] Kan Abe, the paternal grandfather of later Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, was elected to the Diet in 1942 on an anti-Hideki Tojo platform along with future Prime Minister Takeo Miki, who also secured election to the Diet in 1942 on an anti-Tojo platform through mutual assistance with Abe.[66] Another future prime minister who opposed militarism was Tanzan Ishibashi, who spearheaded numerous articles and organisations before and during the war that opposed Japanese colonialism and illiberal authoritarian policies, being aided in his efforts by thinkers such as Kiyoshi Kiyosawa and Kisaburo Yokota.[67]

See also

[edit]- Japanese in the Chinese resistance to the Empire of Japan

- Japanese Resistance to the Imperial House of Japan

- Dissent in the Armed Forces of the Empire of Japan

- Relations between Japanese Revolutionaries and the Comintern and the Soviet Union

- List of Japanese dissidents in Imperial Japan

- Assassination attempts on Hirohito

- Popular Front Incident

- Japanese American service in World War II

- German resistance to Nazism

- Italian resistance

References

[edit]- ^ Notehelfer, F. G (2011-04-14). Kotoku Shusui: Portrait of a Japanese Radical. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521131483.

- ^ Suzumura, Yusuke. "High Treason Incident 1910". Acadamia. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Treacherous Women of Imperial Japan: Patriarchal Fictions, Patricidal Fantasies By Helene Bowen Raddeker Page 7

- ^ "Japanese lawyer made Koreans' cause his own". JoongAng Ilbo. 2013-10-01. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ^ Shimbun. (1903-05). Pacifist, socialist newspaper. A weekly mouthpiece of the socialist Heiminsha (Society of Commoners), this paper served as the leading antiwar vehicle during the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05). The Commoners' Newspaper (Heimin Shimbun) (1903-1905).

- ^ Tamura, Yoshirō (2000). Japanese Buddhism: a cultural history. Translated by Jeffrey Hunter (1st English ed.). Tokyo: Kosei Pub. Co. ISBN 4-333-01684-3. OCLC 45384117.

- ^ Victoria, Brian (1998). Zen at War. Weatherhill page 40, 44,46,43

- ^ Victoria, Brian (1998). Zen at War. Weatherhill. page 43

- ^ Victoria, Brian (1998). Zen at War. Weatherhill. Page 45

- ^ Victoria, Brian (1998). Zen at War. Weatherhill. page 47

- ^ Shields, James Mark, "Zen Internationalism, Zen Revolution: Inoue Shūten, Uchiyama Gudō and the Crisis of (Zen) Buddhist Modernity in Late Meiji Japan" (2022). Faculty Contributions to Books. 262. https://digitalcommons.bucknell.edu/fac_books/262

- ^ Cohen, Jundo (2014). ""Zen at War" by Brian Victoria: Throwing Bombs at Kodo" (PDF).

- ^ buddhanet: Deshimaru

- ^ Richard H. Mitchell. Monumenta Nipponica : Japan's Peace Preservation Law of 1925: Its Origins and Significance. p. 334.

- ^ Gordon, Andrew. Labor and Imperial Democracy in Prewar Japan. p. 178

- ^ "JAPAN: Noble Expiation". Time. 1926-07-12. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ^ e-Study Guide for: East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History

- ^ a b c Driscoll, Mark W. (2020). The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1121-7.

- ^ Japan and the High Treason Incident edited by Masako Gavin, Ben Middleton Page 110

- ^ "Oi, Kentaro". www.ndl.go.jp.

- ^ Connors, Lesley (1987). The emperor's adviser : Saionji Kinmochi and pre-war Japanese politics. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-84165-5. OCLC 1058596530.

- ^ Sugawara, Takeshi (2018-05-03), "Shidehara Kijuro (1872-1951)", in Martel, Gordon (ed.), The Encyclopedia of Diplomacy, Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–2, doi:10.1002/9781118885154.dipl0539, ISBN 978-1-118-88791-2, retrieved 2021-05-15

- ^ The Modern Girl Around the World: Consumption, Modernity, and Globalization, Edited by Alys Eve Weinbaum, Lynn M. Thomas, Priti Ramamurthy, Uta G. Poiger, Modeleine Yue Dong, and Tani E. Barlow, p. 1.

- ^ The 'Modern' Japanese Woman, The Chronicle 5/21/2004:

- ^ "Salon de the". Worldpress. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ "Salon de the". Timeout. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ http://homepage2.nifty.com/strng9/francois/HQ8BGS3ACB03MAJ5.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ Itoh, Mayumi. The Hatoyama Dynasty: Japanese Political Leadership Through the Generations. p. 62

- ^ "「戦争に反対して、命がけで活動した人たちの記録」". kure-sensai.net.

- ^ "「戦前の反戦兵士とその後」II、「聳ゆるマスト」発行の阪口喜一郎の足跡を追ってーー広島・呉で顕彰記念碑建立めざして". kure-sensai.net.

- ^ "「戦前の反戦兵士とその後」II、「聳ゆるマスト」発行の阪口喜一郎の足跡を追ってーー広島・呉で顕彰記念碑建立めざして". kure-sensai.net.

- ^ "「戦前の反戦兵士とその後」II、「聳ゆるマスト」発行の阪口喜一郎の足跡を追ってーー広島・呉で顕彰記念碑建立めざして". kure-sensai.net.

- ^ From Kona to Yenan: The Political Memoirs of Koji Ariyoshi By Koji Ariyoshi page 104–106

- ^ Imperial Eclipse: Japan's Strategic Thinking about Continental Asia before ...By Yukiko Koshiro page 100 chapter 3

- ^ "Japan". Asian Studies. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ From Kona to Yenan: The Political Memoirs of Koji Ariyoshi By Koji Ariyoshi Chapter 12 Re-Education And Sanzo Nosaka Page 123-124

- ^ Pace, Eric (15 November 1993). "Sanzo Nosaka". New York Times. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Postwar Japan By William D. Hoover page 224

- ^ Ienaga, Saburo. Pacific War, 1931–1945. p. 218

- ^ a b c Shibusawa, Naoko (October 2005). ""The Artist Belongs to the People": The Odyssey of Taro Yashima". Journal of Asian American Studies. 8 (3): 257–275. doi:10.1353/jaas.2005.0053. S2CID 145164597. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ "Taro Yashima: Artist for Peace". LibraryPoint. Retrieved 2014-01-15.

- ^ "Retrospective" (PDF). Momaw. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorities Page 333

- ^ The Cultural Front: The Labouring of American Culture in the Twentieth Century by Michael Denning page 145

- ^ Becoming American?: Asian Identity Negotiated Through the Art of Yasuo KuniyoshiBy Shi-Pu Wang page 18

- ^ Wang, ShiPu (2011). "Introduction" (PDF). Becoming American? : the art and identity crisis of Yasuo Kuniyoshi. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824860271. OCLC 794925329, 986700073. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-04. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Glory in a Line: A Life of Foujita--the Artist Caught Between EastBy Phyllis Birnbaum page 276

- ^ "Exhibitions: The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi". Americanart.si.edu. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ^ Kōtoku Shūsui, Portrait of a Japanese Radical By F. G. Notehelfer Page 121

- ^ The Origins of Socialist Thought in Japan By John Crump Page 195

- ^ Nisei linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service, by James C. McNaughton, page 289

- ^ Nisei Linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service. Page 160–161.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers A (1964). An Instance of Treason: Ozaki Hotsumi and the Sorge Spy Ring. Stanford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780804717663.

- ^ Corkill, Edan (31 January 2010). "Sorge's spy is brought in from the cold" – via Japan Times Online.

- ^ "George Ohsawa, Macrobiotics, and Soyfoods Part 1". Soyinfocenter.com. Retrieved 2014-01-16.

- ^ "Sermon" (PDF). Ashland Methodist. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ 上之町生まれの作家 生方敏郎の『古人今人』と『明治大正見聞史』

- ^ A Diary of Darkness. Princeton University Press. 7 September 2008. ISBN 9780691140308.

- ^ "Karl Yoneda". Founds. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume 5By Edward T. James, Janet Wilson James, Paul S. Boyer, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study page 705

- ^ From Kona to Yenan: The Political Memoirs of Koji Ariyoshi by Koji Ariyoshi. Chapter 12 Re-Education and Sanzo Nosaka. Page 123-124

- ^ From Kona to Yenan: The Political Memoirs of Koji AriyoshiBy Koji Ariyoshi page 104

- ^ "U.S.–China Peoples Friendship Association" (PDF). ScholarSpace at University of Hawaii at Manoa. Honolulu, HI, US: USCPFA – Hawai‘i Subregion. 2008-09-26. Retrieved 2019-01-15.

- ^ Hammond, Phillip E.; Machacek, David W. (1999). Soka Gakkai in America: accommodation and conversion (Reprinted. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198293897.

- ^ Kinmonth, Earl H. (1999). "The Mouse That Roared: Saito Takao, Conservative Critic of Japan's "Holy War" in China". Journal of Japanese Studies. 25 (2): 331–360. doi:10.2307/133315. JSTOR 133315.

- ^ "Japanese prime minister's another DNA". Dong-A Ilbo. 28 October 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ^ Keshi, Jiang (c. 2006). "Ishibashi Tanzan's World Economic Theory: The War Resistance of an Economist in the 1930's" (PDF). Princeton University.