Patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or person.[1][2]

The term may be applied to individuals to whom similar roles are ascribed in other religions.

In Christianity

[edit]Saints often become the patrons of places where they were born or had been active. However, there were cases in medieval Europe where a city which grew to prominence obtained for its cathedral the remains or some relics of a famous saint who had lived and was buried elsewhere, thus making them the city's patron saint – such a practice conferred considerable prestige on the city concerned. In Latin America and the Philippines, Spanish and Portuguese explorers often named a location for the saint on whose feast or commemoration day they first visited the place, with that saint naturally becoming the area's patron.[citation needed]

Occupations sometimes have a patron saint who had been connected somewhat with it, although some of the connections were tenuous. Lacking such a saint, an occupation would have a patron whose acts or miracles in some way recall the profession. For example, when the previously unknown occupation of photography appeared in the 19th century, Saint Veronica was made its patron, owing to how her veil miraculously received the imprint of Christ's face after she wiped off the blood and sweat.[3][4][5]

The veneration or commemoration and recognition of patron saints or saints in general is found in Catholicism (including Eastern Catholicism), Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and among some Lutherans and Anglicans.[6] According to the Catholic catechism a person's patron saint, having already attained the beatific vision, is able to intercede with God for their needs.[7]

Apart from Lutheranism and Anglicanism, it is, however, generally discouraged in other Protestant branches, such as Reformed Christianity, where the practice is considered a form of idolatry.[8]

Catholicism

[edit]A saint can be assigned as a patron by a venerable tradition, or chosen by election. The saint is considered a special intercessor with God and the proper advocate of a particular locality, occupation, etc., and merits a special form of religious observance. A term in some ways comparable is "titular", which is applicable only to a church or institution.[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

Lucy of Syracuse, the patron saint of the blind

-

Cecilia of Rome, the patron saint of sacred music and musicians

-

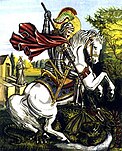

Joan of Arc, the patron saint of France and soldiers

-

Olga of Kiev, the patron saint of widows and converts

-

John of Dukla, the patron saint of Poland and Lithuania

-

Josephine Bakhita, the patron saint of the Catholic Church in Sudan and the Sudanese countries

-

Saint Sava, the patron saint of the Serbs, schools and pupils

In Islam

[edit]Although Islam has no codified doctrine of patronage on the part of saints, it has nevertheless been an important part of both Sunni and Shia Islamic traditions that particularly important classical saints have served as the heavenly advocates for specific Muslim empires, nations, cities, towns, and villages.[10] Martin Lings wrote: "There is scarcely a region in the empire of Islam which has not a Sufi for its Patron Saint."[10]: 119 As the veneration accorded saints often develops purely organically in Islamic climates, in a manner different from Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity, "patron saints" are often recognized through popular acclaim rather than through official declaration.[10] Traditionally, it has been understood that the patron saint of a particular place prays for that place's wellbeing and for the health and happiness of all who live therein.[10]

However, the Wahhabi and Salafi movements have latterly attacked the veneration of saints (as patron or otherwise), which they claim are a form of idolatry or shirk.[10] More mainstream Sunni clerics have critiqued this argument since Wahhabism first emerged in the 18th century.[11]

In Druze faith

[edit]Elijah and Jethro (Shuaib) are considered patron saints of the Druze people.[12][13] In the Old Testament, Jethro was Moses' father-in-law, a Kenite shepherd and priest of Midian.[14] Muslim scholars and the Druze identify Jethro with the prophet Shuaib, also said to come from Midian.[15] Shuaib or Jethro of Midian is considered an ancestor of the Druze who revere him as their spiritual founder and chief prophet.[16]

Druze identify Elijah as "al-Khidr".[17] Druze, like some Christians, believe that the Prophet Elijah came back as Saint John the Baptist,[17][18] since they believe in reincarnation and the transmigration of the soul, Druze believe that El Khidr and Saint John the Baptist are one and the same; along with Saint George.[18]

Due to the Christian influence on the Druze faith, two Christian saints become the Druze's favorite venerated figures: Saint George and Saint Elijah.[19] Thus, in all the villages inhabited by Druzes and Christians in central Mount Lebanon a Christian church or Druze maqam is dedicated to either one of them.[19] According to scholar Ray Jabre Mouawad the Druzes appreciated the two saints for their bravery: Saint George because he confronted the dragon and the Prophet Elijah because he competed with the pagan priests of Baal and won over them.[19] In both cases the explanations provided by Christians is that Druzes were attracted to warrior saints that resemble their own militarized society.[19]

In Eastern religions

[edit]In Hinduism, certain sects may devote themselves to the veneration of a saint, such as the Balmiki sect that reveres Valmiki.[20]

Buddhism also includes the idea of protector deities, which are called "Dharma protectors" (Dharmapala).

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Slocum, Robert Boak; Armentrout, Donald S. (2000). "Patronal Feast". An Episcopal Dictionary of the Church: A User-Friendly Reference for Episcopalians. New York: Church Publishing, Inc. p. 390. ISBN 0-89869-211-3.

- ^ "patron saint". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. 2006. p. 1290. ISBN 0-618-70172-9.

- ^ C.W.G.; R.G. (11 September 1852). "St. Veronica (Vol. vi., p.199)". Notes and Queries. 6 (150). London: 252.

- ^ "Archaeological Intelligence". The Archaeological Journal. 7: 413. 1850. doi:10.1080/00665983.1850.10850808.

- ^ Butler, Alban (2000). "St. Veronica (First Century)". In Doyle, Peter (ed.). Lives of the Saints: July (New full ed.). Tunbridge Wells: Burns & Oates. pp. 84–86. ISBN 0-86012-256-5. OCLC 877793679 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brandsrud, Megan (30 November 2022). "Honor Advent through the saints". Living Lutheran. Retrieved 29 December 2023.

- ^ Gibson, Henry (1882). "Twenty-Fifth Instruction". Catechism Made Easy: Being a Familiar Explanation of the Catechism of Christian Doctrine (No. 2). Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). London: Burns and Oates. p. 310 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Duke, A.C.; Lewis, Gillian; Pettegree, Andrew, eds. (1992). "Managing a country parish: A country pastor's advice to his successor". Calvinism in Europe, 1540–1610: A Collection of Documents. p. 53. ISBN 0-7190-3552-X. OCLC 429210690.

- ^ Knight, Kevin (2020). "Patron Saints". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Lings, Martin (2005) [1983]. What is Sufism?. Lahore: Suhail Academy. pp. 119–120 etc.

- ^ Commins, David (2009). The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia. I.B.Tauris. p. 59.

Abd al-Latif, who would become the next supreme religious leader ... enumerated the harmful views that Ibn Jirjis openly espoused in Unayza: Supplicating the dead is not a form of worship but merely calling out to them, so it is permitted. Worship at graves is not idolatry unless the supplicant believes that buried saints have the power to determine the course of events. Whoever declares that there is no god but God and prays toward Mecca is a believer.

- ^ a b Fukasawa, Katsumi (2017). Religious Interactions in Europe and the Mediterranean World: Coexistence and Dialogue from the 12th to the 20th Centuries. Taylor & Francis. p. 310. ISBN 9781351722179.

- ^ Israeli, Raphael (2009). Peace is in the Eye of the Beholder. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 244. ISBN 9783110852479.

Nabi Shu'eib, biblical Jethro, is the patron saint of the Druze.

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Mackey, Sandra (2009). Mirror of the Arab World: Lebanon in Conflict. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-3933-3374-9.

- ^ A Political and Economic Dictionary of the Middle East. Routledge. 2013. ISBN 9781135355616.

- ^ a b Swayd, Samy (2015). Historical Dictionary of the Druzes. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 77. ISBN 9781442246171.

since Elijah was central to Druzism, one may safely argue that the settlement of Druzes on Mount Carmel had partly to do with Elijahʼs story and devotion. Druzes, like some Christians, believe that Elijah came back as John the Baptist

- ^ a b Bennett, Chris (2010). Cannabis and the Soma Solution. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 77. ISBN 9781936296323.

transmigration of the soul is a Druze tenet, and Druze believe that El Khidr and John the Baptist are one and the same. (Gibbs, 2008) The mythology of Khizr is thought to go back even further than the time of John the Baptist or Elija

- ^ a b c d Beaurepaire, Pierre-Yves (2017). Religious Interactions in Europe and the Mediterranean World: Coexistence and Dialogue from the 12th to the 20th Centuries. Taylor & Francis. pp. 310–314. ISBN 9781351722179.

- ^ Kananaikil, Jose (1983). Scheduled Castes and the Struggle Against Inequality: Strategies to Empower the Marginalised. Indian Social Institute. p. 17.

External links

[edit]- Catholic Online: Patron Saints

- Henry Parkinson (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.