Healthcare in Canada

| Part of a series on |

| Healthcare in Canada |

|---|

|

|

|

Healthcare in Canada is delivered through the provincial and territorial systems of publicly funded health care, informally called Medicare.[1][2] It is guided by the provisions of the Canada Health Act of 1984,[3] and is universal.[4]: 81 The 2002 Royal Commission, known as the Romanow Report, revealed that Canadians consider universal access to publicly funded health services as a "fundamental value that ensures national health care insurance for everyone wherever they live in the country".[5][6]

Canadian Medicare provides coverage for approximately 70 percent of Canadians' healthcare needs, and the remaining 30 percent is paid for through the private sector.[7][8] The 30 percent typically relates to services not covered or only partially covered by Medicare, such as prescription drugs, eye care, medical devices, gender care, psychotherapy, physical therapy and dentistry.[7][8] About 65-75 percent of Canadians have some form of supplementary health insurance related to the aforementioned reasons; many receive it through their employers or use secondary social service programs related to extended coverage for families receiving social assistance or vulnerable demographics, such as seniors, minors, and those with disabilities.[9]

According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), by 2019, Canada's aging population represents an increase in healthcare costs of approximately one percent a year, which is a modest increase.[7] In a 2020 Statistics Canada Canadian Perspectives Survey Series (CPSS), 69 percent of Canadians self-reported that they had excellent or very good physical health—an improvement from 60 percent in 2018.[10] In 2019, 80 percent of Canadian adults self-reported having at least one major risk factor for chronic disease: smoking, physical inactivity, unhealthy eating or excessive alcohol use.[11] Canada has one of the highest rates of adult obesity among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries attributing to approximately 2.7 million cases of diabetes (types 1 and 2 combined).[11] Four chronic diseases—cancer (a leading cause of death), cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and diabetes account for 65 percent of deaths in Canada.[11]

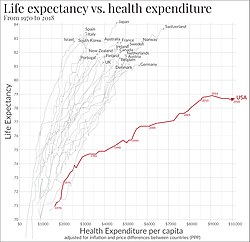

In 2021, the Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that healthcare spending reached $308 billion, or 12.7 percent of Canada's GDP for that year.[12] In 2022 Canada's per-capita spending on health expenditures ranked 12th among healthcare systems in the OECD.[13] Canada has performed close to the average on the majority of OECD health indicators since the early 2000s,[14] and ranks above average for access to care, but the number of doctors and hospital beds are considerably below the OECD average.[15] The Commonwealth Funds 2021 report comparing the healthcare systems of the 11 most developed countries ranked Canada second-to-last.[16] Identified weaknesses of Canada's system were comparatively higher infant mortality rate, the prevalence of chronic conditions, long wait times, poor availability of after-hours care, and a lack of prescription drugs coverage.[17] An increasing problem in Canada's health system is a shortage of healthcare professionals and hospital capacity.[18][19]

Canadian healthcare policy

[edit]The primary objective of the Canadian healthcare policy, as set out in the 1984 Canada Health Act (CHA), is to "protect, promote and restore the physical and mental well-being of residents of Canada and to facilitate reasonable access to health services without financial or other barriers."[20][21] The federal government ensures compliance with its requirements that all Canadians have "reasonable access to medically necessary hospital, physician, and surgical-dental services that require a hospital" by providing cash to provinces and territories through the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) based on their fulfilling certain "criteria and conditions related to insured health services and extended health care services."[21]

In his widely cited 1987 book, Malcolm G. Taylor traced the roots of Medicare and federal-provincial negotiations involving "issues of jurisdiction, cost allocations, revenue transfers, and taxing authorities" that resulted in the current system that provides healthcare to "Canadians on the basis of need, irrespective of financial circumstances."[22][23]

Monitoring and measuring healthcare in Canada

[edit]Health Canada, under the direction of the Health Minister, is the ministry responsible for overseeing Canada's healthcare, including its public policies and implementations. This includes the maintenance and improvement of the health of the Canadian population, which is "among the healthiest in the world as measured by longevity, lifestyle and effective use of the public health care system."[24]

Health Canada, a federal department, publishes a series of surveys of the healthcare system in Canada.[25] Although life-threatening cases are dealt with immediately, some services needed are non-urgent and patients are seen at the next-available appointment in their local chosen facility.

In 1996, in response to an interest in renewing its healthcare system, the federal government established the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHRSF) in the 1996 federal budget to conduct research in collaboration with "provincial governments, health institutions, and the private sector" to identify the successes and failures in the health system.[26]: 113

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) is a not-for-profit, independent organization established by the provincial, territorial, and federal government to make healthcare information publicly available.[27] The CIHI was established in 1994 to serve as a national "coordinating council and an independent institute for health information" in response to the 1991 report, "Health Information for Canada" produced by the National Task Force on Health Information.[28] In 1994, the CIHI merged the Hospital Medical Records Institute (HMRI) and The Management Information Systems (MIS) Group.[28]

Reports include topics such as the evaluating and suggested improvements for the efficiency of healthcare services. Regions that were similar in factors such as education levels and immigration numbers were found to have different efficiency levels in health care provision. The study concluded if increased efficiency of the current system was set as a goal, the death rate could be decreased by 18%-35%.[29] The study notes that supporting physician leadership and facilitating engagement of the care providers could reap great gains in efficiency. Additionally, the study suggested facilitating the exchange of information and interaction between health providers and government figures as well as flexible funding would also contribute to the improvement and solve the problem of differences in regional care by allowing regions to determine the needs of their general populace and meet those needs more efficiently by allowing target-specific allocation of funds.[30]

For 24 years, the CIHI has produced an annual detailed report updating "National Health Expenditure Trends" which includes data tables with the most recent report published in January 2021.[31][32] Other CIHI research topics include hospital care, organ and joint replacements, health system performance, seniors and aging, health workforce, health inequality, quality and safety, mental health and addictions, pharmaceuticals, international comparisons, emergency care, patient experience, residential care, population health, community care, patient outcomes, access and wait times, children and youth, and First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

In 2003, at the First Ministers' Accord on Health Care Renewal, the Health Council of Canada (HCC)—an independent national agency—was established to monitor and report on Canada's healthcare system.[33] For over a decade, until 2014, the HCC produced 60 reports on access and wait times, health promotion, seniors healthcare, aboriginal healthcare, home and community care, pharmaceuticals management, and primary health care.[34]

Demographics

[edit]

By February 2024, the median age in Canada was 40.6 years in 2023[35] compared to 39.5 in 2006.[36]

By July 2020, there were 6,835,866 individuals who were 65 years old and older and 11,517 centenarians.[37] The same data reported that by July 2020, 16% of Canadians were 14-years-old or under, 66.5% were between the ages of 15 and 65, and 17.5% were 65 years and older.[37]

Canada's population is aging, like that of many other countries.[38] By 2016, there were about six million seniors in Canada, which then had a population of approximately 34 million.[39] This significantly influences Canada's healthcare services;[38] by 2019, Canada's aging population represented a modest increase in healthcare costs of about 1% a year.[7]

Since the 2010s, Statistics Canada health research on aging has focused on "chronic diseases," "social isolation" and senior's mental health needs, and "transitions to institutional care" including long-term care.[38] The eight chronic conditions that are prevalent in one out of ten seniors include high blood pressure, arthritis, back problems, eye problems, heart disease, osteoporosis, diabetes and urinary incontinence, with many seniors having multiple chronic conditions.[38] Those with chronic conditions are "associated with higher use of home-care services and need for formal-care providers."[38]

Ninety percent of Canadians agree that Canada should have a "national seniors strategy to address needs along the full continuum of care."[39]

Current status

[edit]The government guarantees the quality of care through federal standards. The government does not participate in day-to-day care or collect any information about an individual's health, which remains confidential between a person and their physician.[40] In each province, each doctor handles the insurance claim against the provincial insurer. There is no need for the person who accesses healthcare to be involved in billing and reclaim. Private health expenditure accounts for 30% of health care financing.[41]

The Canada Health Act does not cover prescription drugs, home care, or long-term care or dental care.[40] Provinces provide partial coverage for children, those living in poverty, and seniors.[40] Programs vary by province. In Ontario, for example, most prescriptions for youths under the age of 24 are covered by the Ontario health insurance plan if no private insurance plan is available.[42]

Competitive practices such as advertising are kept to a minimum, thus maximizing the percentage of revenues that go directly towards care. Costs are paid through funding from federal and provincial general tax revenues, which include income taxes, sales taxes, and corporate taxes. In British Columbia, taxation-based funding was (until January 1, 2020) supplemented by a fixed monthly premium that was waived or reduced for those on low incomes.[43] In Ontario, there is an income tax identified as a health premium on taxable income above $20,000.[44]

In addition to funding through the tax system, hospitals and medical research are funded in part by charitable contributions. For example, in 2018, Toronto's Hospital for Sick Children embarked on campaign to raise $1.3 billion to equip a new hospital.[45] Charities such as the Canadian Cancer Society provide assistance such as transportation for patients.[46] There are no deductibles on basic health care and co-pays are extremely low or non-existent (supplemental insurance such as Fair Pharmacare may have deductibles, depending on income). In general, user fees are not permitted by the Canada Health Act, but physicians may charge a small fee to the patient for reasons such as missed appointments, doctor's notes, and prescription refills done over the phone. Some physicians charge "annual fees" as part of a comprehensive package of services they offer their patients and their families. Legally, such charges must be completely optional and can only be for non-essential health options,[40] however, some clinics have allegedly broken these rules,[47] and provincial agencies have pursued injunctions and investigations.[48][49]

Benefits and features

[edit]Health cards are issued by provincial health ministries to individuals who enroll for the program, though newcomers must wait up to three months after they arrive in the province,[50] and everyone receives the same level of care once they receive one.[51] Most essential basic care is covered, including maternity but excluding mental health and home care.[52] Infertility costs are not covered in any province other than Quebec, though they are now partially covered in some other provinces.[53] In some provinces, private supplemental plans are available for those who desire private rooms if they are hospitalized. Cosmetic surgery and some forms of elective surgery are not considered essential care and are generally not covered. For example, Canadian health insurance plans do not cover non-therapeutic circumcision.[54] These can be paid out-of-pocket or through private insurers.

Basic health coverage is not affected by loss or change of jobs, cannot be denied due to unpaid premiums, and is not subject to lifetime limits or exclusions for pre-existing conditions. The Canada Health Act deems that essential physician and hospital care be covered by the publicly funded system, but each province has reasons to determine what is considered essential, and where, how and who should provide the services. There are some provinces that are moving towards private health care away from public health care.[citation needed] The result is that there is a wide variance in what is covered across the country by the public health system, particularly in more controversial or expensive areas, such as mental health, substance use treatment, in-vitro fertilization,[55] gender-affirming surgery,[56] or autism treatments.[40]

Canada (with the exception of the province of Quebec) is one of the few countries with a universal healthcare system that does not include coverage of prescription medication (other such countries are Russia and some of the former USSR republics[57]). Residents of Quebec who are covered by the province's public prescription drug plan pay an annual premium of $0 to $660 when they file their Quebec income tax return.[58][59]

Over the past two decades, at least some provinces have introduced some universal prescription drug insurance. Nova Scotia has Family Pharmacare, introduced in 2008 by Rodney MacDonald's Progressive Conservative government.[60] However, residents do not automatically receive it through their health care as they must register separately for it, and it covers a limited range of prescriptions. No premiums are charged. A deductible and out-of-pocket maximum for copayments are set as a percentage of taxable income of two years before.[61]

Pharmaceutical medications are covered by public funds in some provinces for the elderly or indigent,[62] through employment-based private insurance or paid for out-of-pocket. In Ontario, eligible medications are provided at no cost for covered individuals aged 24 and under.[63] Most drug prices are negotiated with suppliers by each provincial government to control costs but more recently, the Council of the Federation announced an initiative for select provinces to work together to create a larger buying block for more leverage to control costs of pharmaceutical drugs.[64] More than 60 percent of prescription medications are paid for privately in Canada.[40] Family physicians ("General Practitioners") are assigned to individuals using provincial waitlist registry systems.[65] If a patient wishes to see a specialist or is counseled to see a specialist by their GP, a referral is made by a GP in the local community. Preventive care and early detection are considered critical.[citation needed]

Coverage

[edit]Mental health

[edit]The Canada Health Act covers the services of psychiatrists, medical doctors with additional training in psychiatry. In Canada, psychiatrists tend to focus on the treatment of mental illness with medication.[66] However, the Canada Health Act excludes care provided in a "hospital or institution primarily for the mentally disordered."[67] Some institutional care is provided by provinces. The Canada Health Act does not cover treatment by a psychologist[68] or psychotherapist unless the practitioner is also a medical doctor. Goods and Services Tax or Harmonized Sales Tax (depending on the province) applies to the services of psychotherapists.[69] Some coverage for mental health care and substance abuse treatment may be available under other government programs. For example, in Alberta, the province provides funding for mental health care through Alberta Health Services.[70] Most or all provinces and territories offer government-funded drug and alcohol addiction rehabilitation, although waiting lists may exist.[71] The cost of treatment by a psychologist or psychotherapist in Canada has been cited as a contributing factor in the high suicide rate among first responders such as police officers, EMTs and paramedics. According to a CBC report, some police forces "offer benefits plans that cover only a handful of sessions with community psychologists, forcing those seeking help to join lengthy waiting lists to seek free psychiatric assistance."[72]

Oral health

[edit]Among the OECD countries, Canada ranks second to last in the public funding of oral healthcare.[citation needed] Those who need dental care are usually responsible for the finances and some may benefit from the coverage available through employment, under provincial plans, or private dental care plans. "As opposed to its national system of public health insurance, dental care in Canada is almost wholly privately financed, with approximately 60% of dental care paid through employment-based insurance, and 35% through out-of-pocket expenditures. Of the approximately 5% of publicly financed care that remains, most has focused on socially marginalized groups (e.g., low-income children and adults), and is supported by different levels of government depending on the group insured."[73] It is true that compared to primary care checkups, dental care checkups depend on the ability of people being able to pay those fees.

Studies in Quebec and Ontario provide data on the extent of dental health care.[citation needed] For example, studies in Quebec showed that there was a strong relation among dental services and the socioeconomic factors of income and education whereas in Ontario older adults heavily relied on dental insurance with visits to the dentist. "According to the National Public Health Service in 1996/1997, it showed a whopping difference of people who were in different classes. About half of Canadians aged 15 or older (53%) reported having dental insurance. Coverage tended to be highest among middle-aged people. At older ages, the rate dropped, and only one-fifth of the 65-or-older age group (21%) was covered."[74] Attributes that can contribute to these outcomes is household income, employment, as well as education. Those individuals who are in the middle class may be covered through the benefits of their employment whereas older individuals may not due to the fact of retirement.

Under the government healthcare system in Canada, routine dental care is not covered.[75][76] There are a couple of provinces that offer child prevention programs such as Nova Scotia and Quebec.[77] Other provinces make patients pay for medical dental procedures that are performed in the hospital. Some dental services that are possibly not covered by Medicare may include cavity fillings, routine dental check-ups, restorative dental care, and preventive care, dentures, dental implants, bridges, crowns, veneers, and in-lays, X-rays, and orthodontic procedures.

In 2022, however, the federal government announced the creation of a new Canada Dental Benefit which reimburses low- to middle-income parents up to $650 of dental fees per child.[78] This was a transitional policy on the way to universal, public coverage of dental care. In 2023, the government established the Canadian Dental Care Plan, which began a staggered enrolment rollout in December 2023, to pay costs for covered dental services of eligible residents.[79]

Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and massage therapy

[edit]Coverage for services by physiotherapists, occupational therapists (also known as OTs) and Registered Massage Therapists (RMTs) varies by province. For example, in Ontario the provincial health plan, OHIP, does cover physiotherapy following hospital discharge and occupational therapy[80] but does not cover massage therapy. To be eligible for coverage for physiotherapy in Ontario, insured individuals must have been discharged as an inpatient of a hospital after an overnight stay and require physiotherapy for the condition, illness or injury, or be age 19 or younger or age 65 or older.[81]

Other coverage limitations

[edit]Coverage varies for care related to the feet. In Ontario, as of 2019, Medicare covers between $7–16 of each visit to a registered podiatrist up to $135 per patient per year, plus $30 for x-rays.[82] Although the elderly, as well as diabetic patients, may have needs that greatly exceed that limit, such costs would have to be covered by patients or private supplemental insurance.

As of 2014, most, but not all provinces and territories provide some coverage for sex reassignment surgery (also known as gender confirming surgery) and other treatment for gender dysphoria.[83] In Ontario, sex reassignment surgery requires prior approval before being covered.[84]

However, access to care does not meet WPATH guidelines in provinces covering 84% of Canada's population (excepting British Columbia, Prince Edward Island and Yukon Territory). Wait times are extensive for gender care in Canada, and can be as long as eight years.[85]

There are wide discrepancies in coverage for various assistive devices such as wheelchairs and respiratory equipment in Canada. Ontario, which has one of the most generous programs, pays 75% of the cost for listed equipment and supplies for persons with a disability requiring such equipment or supplies for six months or longer.[86] The program does not have age or income restrictions. As with other health coverage, veterans and others covered by federal programs are not eligible under the provincial program. Only certain types of equipment and supplies are covered, and within categories only approved models of equipment from approved vendors are covered, and vendors may not charge more than specified prices established by the government.[87]

Nursing homes and home care

[edit]Home care is an "extended" service, and is therefore not an insured service under the Canada Health Act.[88]: 10 Home care is not considered to be a medically necessary service, like hospital and physician services, and provincial and territorial governments are under no obligation to provide home care services.[88]: 9 In their 2009 report on home care in Canada, the Canadian Healthcare Association (CHA ) said that there was an increase in chronic disease rates as Canada's population aged.[88]: 9 Home care is generally considered to be a lower cost alternative at a time when governments are concerned about the cost of healthcare and is generally the preferred option for seniors.[88]: 9

One in four caregivers provide care related to aging.[38] A 2016 study published in the Journal of Canadian Studies said that with an increasing elder population, in Canada, the supply of home care aids (HCA)s was not meeting the demand required to provide adequate nursing home care and home care in an increasingly complex care system.[89] Home care aids face intense job precarity, inadequate staffing levels as well as increasingly complex needs including different types of routinized, assembly-lines types of work, and cost-cutting on equipment and supplies.[89] They also work in situations where there are more occupational hazards, which can include aggressive pets, environmental tobacco smoke, oxygen equipment, unsafe neighborhoods, and pests.[90][Notes 1] As the role of home care aids evolves, so does the need for more training and instruction. Nurses and HCAs are expected to think critically and execute real-time, and make evidence-based care decisions.[91]

Indigenous peoples

[edit]The largest group the federal government is directly responsible for is First Nations. Native peoples are a federal responsibility and the federal government guarantees complete coverage of their health needs. For the last twenty years and despite health care being a guaranteed right for First Nations due to the many treaties the government of Canada signed for access to First Nations lands and resources, the amount of coverage provided by the Federal government's Non-Insured Health Benefits program has diminished drastically for optometry, dentistry, and medicines. Status First Nations individuals qualify for a set number of visits to the optometrist and dentist, with a limited amount of coverage for glasses, eye exams, fillings, root canals, etc. For the most part, First Nations people use normal hospitals and the federal government then fully compensates the provincial government for the expense. The federal government also covers any user fees the province charges. The federal government maintains a network of clinics and health centers on First Nations reserves. At the provincial level, there are also several much smaller health programs alongside Medicare. The largest of these is the health care costs paid by the workers' compensation system. Regardless of federal efforts, healthcare for First Nations has generally not been considered effective.[92][93][94] Despite being a provincial responsibility, the large health costs have long been partially funded by the federal government.

Healthcare spending

[edit]While the Canadian healthcare system has been called a single payer system, Canada "does not have a single health care system" according to a 2018 Library of Parliament report.[95] The provinces and territories provide "publicly funded health care" through provincial and territorial public health insurance systems.[95] The total health expenditure in Canada includes expenditures for those health services not covered by either federal funds or these public insurance systems, that are paid by private insurance or by individuals out-of-pocket.[95]

In 2017, the Canadian Institute for Health Information reported that healthcare spending is expected to reach $242 billion, or 11.5% of Canada's gross domestic product for that year.

The provinces and territories health spending accounted for approximately "64.2% of total health expenditure" in 2018. [95][96] Public sources of revenue for the public healthcare system include provincial financing which represented 64.2% of the total in 2018. This includes funds transferred from the federal government to the provinces in the form of the CHT.[95] Direct funding from the federal government, as well as funds from municipal governments and social security funds represented 4.8% in 2018.[95][96]: 11

According to the CIHI 2019 report, since 1997, the 70–30 split between public and private sector healthcare spending has remained relatively consistent with approximately 70% of Canada's total health expenditures from the public sector and 30% from the private sector.[7][8] Public-sector funding, which has represented approximately 70% of total health expenditure since 1997, "includes payments by governments at the federal, provincial/territorial and municipal levels and by workers' compensation boards and other social security schemes".[96]: 11

Private sector funding

[edit]Private sector funding is regulated under the Canada Health Act, (CHA) which sets the conditions with which provincial/territorial health insurance plans must comply if they wish to receive their full transfer payments from the federal government. The CHA does not allow charges to insured persons for insured services (defined as medically necessary care provided in hospitals or by physicians). Most provinces have responded through various prohibitions on such payments.[8]

Private-sector health care dollars, which has represented about 30% of total health expenditure, "consists primarily of health expenditures by households and private insurance firms".[96] In 2018, private sector funding for health care, accounted for 31% of the total health expenditures.[95] "includes primarily private insurance and household expenditures."[95]

The top categories of private sector expenditures account for 66% of this spending, and include pharmaceuticals, and professional services such as dental and vision care services.[7] Only 10% of these services are paid for by the public sector.[7] In 2017, 41% of private sector expenses were paid by private insurance companies. The amount of out-of-pocket spending represented 49% of private sector spending.[7]

A 2006 in-depth CBC report, the Canadian system is for the most part publicly funded, yet most of the services are provided by private enterprises.[97] In 2006, most doctors do not receive an annual salary, but receive a fee per visit or service.[97] According to Dr. Albert Schumacher, former president of the Canadian Medical Association, an "estimated 75% of Canadian health care services are delivered privately but funded publicly."[97]

"Front line practitioners whether they're GP's or specialists, by and large, are not salaried. They're small hardware stores. Same thing with labs and radiology clinics ... The situation we are seeing now are more services around not being funded publicly but people having to pay for them, or their insurance companies. We have sort of a passive privatization."

— Dr. Albert Schumacher. CBC. December 1, 2006.

Private clinics are permitted and are regulated by the provinces and territories. Private clinics can charge above the agreed-upon fee schedule if they are providing non-insured services, treating non-insured persons, or based in Quebec, due to a court decision.[98] This may include those eligible under automobile insurance or worker's compensation, in addition to those who are not Canadian residents, or providing non-insured services. This provision has been controversial among those seeking a greater role for private funding.

It's been suggested[99] that the apparent success of the private telehealth provider Maple, with its hundreds of thousands of paying users, indicates the existence of a rapidly growing private healthcare tier. Maple has come under criticism for affordability,[100] as appointments with a general practitioner on Maple can cost over $200 per visit.[101]

Private health insurance

[edit]In Canada private health insurances is mainly provided through employers.[102]

By 2016, "health care dollars from private insurance were $788 per capita" in 2016, which represents an annual growth rate of 6.4% from 1988 to 2016.[95]

According to a 2004 OECD report, 75% of Canadians had some form of supplementary private health insurance.[102]

In many provinces, purchasing duplicate health insurance for care already covered by the government's health insurance plan is prohibited.[103][verification needed]

Out-of-pocket expenses

[edit]From 1988 to 2016, the amount of out‑of‑pocket expenses paid by individuals had grown by about 4.6% annually. By 2016, it amounted to $972 per capita.[95]

Major healthcare expenses

[edit]The highest health expenditures were hospitals—$51B in 2009 up from $45.4B, representing 28.2% in 2007, followed by pharmaceuticals—$30B in 2009 up from $26.5B, representing 16.5% in 2007, and physician services—$26B in 2009, up from $21.5B or 13.4% in 2007.[104][105]

The proportion spent on hospitals and physicians has declined between 1975 and 2009 while the amount spent on pharmaceuticals has increased.[106] Of the three biggest health care expenses, the amount spent on pharmaceuticals has increased the most. In 1997, the total price of drugs surpassed that of doctors. In 1975, the three biggest health costs were hospitals ($5.5B/44.7%), physicians ($1.8B/15.1%), and medications ($1.1B/8.8%).[105]

By 2018, drugs (both prescription and non-prescription) had become the second largest expenditure representing 15.3% of the total, hospitals at 26.6% represented the largest sector by expenses, and physician services represented 15.1% of the total.[32]

Hospitals

[edit]Hospitals have consistently been the top healthcare expenditure representing 26.6% of total healthcare expenditures in Canada in 2018.[32]

Hospital capacity in Canada peaked in 1970. Since then, per-capita hospital bed capacity has been reduced by 63%.[107]

Hospital care is delivered by publicly funded hospitals in Canada. Most of the public hospitals, each of which are independent institutions incorporated under provincial Corporations Acts, are required by law to operate within their budget.[108] Amalgamation of hospitals in the 1990s has reduced competition between hospitals.

An OECD study in 2010 noted that there were variations in care across the different provinces in Canada. The study found that there was a difference in hospital admission rates depending on the number of people and what province they lived in. Typically, provinces with low population counts had higher hospital admission rates due to there being a lack of doctors and hospitals in the region.[109]

Pharmaceuticals

[edit]By 2018, drugs—both prescription and non-prescription—were the second largest healthcare expenditure in Canada at 15.3% of the total.[32]

According to the December 2020 CIHI report, in 2019 public drug programs expenditures were $15 billion, representing a one-year increase of 3%.[110] The drug that contributed to about 26% of the increase in spending were drugs for diabetes.[110] In 2018, hepatitis C drugs were the 2nd highest contributor to increase in pharmaceutical spending. In 2019, this decreased by 18% as fewer people took these drugs. In 2019, spending on biologics increased from 9% to 17% of public spending for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease and similar conditions.[110]

By 1997, the total cost of pharmaceuticals surpassed the total cost of physician services and has remained in second place, after hospitals in terms of total annual health expenditures.[106] The proportion spent on hospitals and physicians has declined between 1975 and 2009 while the amount spent on pharmaceuticals has increased.[106] Of the three biggest health care expenses, the amount spent on pharmaceuticals has increased the most. In 1997, the total price of drugs surpassed that of doctors. In 1975, the three biggest health costs were hospitals ($5.5B/44.7%), physicians ($1.8B/15.1%), and medications ($1.1B/8.8%).[105]

According to the April 2018 report entitled Pharmacare Now: Prescription Medicine Coverage for All Canadians issued by the House of Commons Standing Committee on Health "spending on medicines dispensed outside hospitals accounted for 85% of total drug expenditures in 2017."[95]

The CHA requires that public provincial and territorial health insurance policies must cover all "medicines used within the hospital setting...out‑of‑hospital drug expenditures are paid for by private insurance and individuals, as well as by provincial health insurance for certain population groups".[95] Public provincial and territorial health insurance covers "43% of out‑of‑hospital medicine"; private insurance covers 35%; and the remainder, which represents 22% is paid by individuals out-of-pocket.[95]

Pharmaceutical costs are set at a global median by the government price controls.

Physician services

[edit]The third largest healthcare expenditure in Canada are physician services which represented 15.1% of the total in 2018.[32] From 1997 through 2009, the proportion of total annual health expenditures spent on physicians declined.[106]

In 2007, physician services cost $21.5B representing 13.4% of total health expenditures.[104] By 2009, that had increased to $26B.[104]

Number of physicians

[edit]Canada, like its North American neighbor the United States, has a ratio of practising physicians to a population that is below the OECD average[111] but a level of practising nurses that is higher than the OECD average, though below the US average in 2016.[112]

A record number of doctors was reported in 2012 with 75,142 physicians, though this includes doctors who have partially or completely opted out of the public health system, which has occurred at record numbers in Quebec.[113] The gross average salary was $328,000. Out of the gross amount, doctors pay for taxes, rent, staff salaries and equipment.[114] Recent reports indicate that Canada has an imbalanced supply of specialists to general physicians, and a severe shortage of family doctors, with 10 million Canadians projected to lack access to primary care,[115][116][117] compounded by new graduates opting against selecting family medicine,[118] and communities in rural, remote and northern regions, experience particularly acute shortages.[119][120] Limitations on which and how many physicians can complete Canada's required two year medical residency may prevent trained doctors from acquiring a license to practice medicine, leading to an effective shortage.[121] Burnout and mental health reasons may also play a role, as in 2021, 48% of physicians polled by the Canadian Medical Association screened positive for depression.[122]

Physician payment

[edit]Basic services are provided by private doctors (since 2002 they have been allowed to incorporate), with the entire fee paid for by the government at the same rate. Most family doctors receive a fee per visit. These rates are negotiated between the provincial governments and the province's medical associations, usually on an annual basis. The fee for service model has been criticized for deterring physicians from becoming family doctors in British Columbia.[123]

CTV news reported that, in 2006, family physicians in Canada made an average of $202,000 a year.[124]

In 2018, to draw attention to the low pay of nurses and the declining level of service provided to patients, more than 700 physicians, residents and medical students in Quebec signed an online petition asking for their pay raises to be canceled.[125]

Professional organizations

[edit]Each province regulates its medical profession through a self-governing College of Physicians and Surgeons, which is responsible for licensing physicians, setting practice standards, and investigating and disciplining its members.

The national doctors association is called the Canadian Medical Association (CMA);[126] it describes its mission as "To serve and unite the physicians of Canada and be the national advocate, in partnership with the people of Canada, for the highest standards of health and health care."[127]

Since the passage of the 1984 Canada Health Act, the CMA itself has been a strong advocate of maintaining a strong publicly funded system, including lobbying the federal government to increase funding, and being a founding member of (and active participant in) the Health Action Lobby (HEAL).[128]

In December 2008, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada reported a critical shortage of obstetricians and gynecologists. The report stated that 1,370 obstetricians were practising in Canada and that number is expected to fall by at least one-third within five years. The society is asking the government to increase the number of medical school spots for obstetrics and gynecologists by 30 percent a year for three years and also recommended rotating placements of doctors into smaller communities to encourage them to take up residence there.[129]

Some provincial medical associations have argued for permitting a larger private role. To some extent, this has been a reaction to strong cost control; CIHI estimates that 99% of physician expenditures in Canada come from public sector sources, and physicians—particularly those providing elective procedures who have been squeezed for operating room time—have accordingly looked for alternative revenue sources. The CMA presidency rotates among the provinces, with the provincial association electing a candidate who is customarily ratified by the CMA general meeting. Day's selection was sufficiently controversial that he was challenged—albeit unsuccessfully—by another physician.[130]

Provincial associations

[edit]Because healthcare is deemed to be under provincial/territorial jurisdiction, negotiations on behalf of physicians are conducted by provincial associations such as the Ontario Medical Association. The views of Canadian doctors have been mixed, particularly in their support for allowing parallel private financing. The history of Canadian physicians in the development of Medicare has been described by C. David Naylor.[131]

In 1991, the Ontario Medical Association agreed to become a province-wide closed shop, making the OMA union a monopoly. Critics argue that this measure has restricted the supply of doctors to guarantee its members' incomes.[132] In 2008, the Ontario Medical Association and the Ontario government agreed to a four-year contract with a 12.25% doctors' pay raise, which was expected to cost Ontarians an extra $1 billion. Ontario's then-premier Dalton McGuinty said, "One of the things that we've got to do, of course, is ensure that we're competitive ... to attract and keep doctors here in Ontario ..."[133]

Healthcare spending and an aging population

[edit]By 2019, Canada's aging population represented a modest increase in healthcare costs of about 1% a year.[7] It is also the greatest at the extremes of age at a cost of $17,469 per capita in those older than 80 and $8,239 for those less than 1 year old in comparison to $3,809 for those between 1 and 64 years old in 2007.[134]

Comparing healthcare spending over time

[edit]Healthcare spending in Canada (in 1997 dollars) has increased each year between 1975 and 2009, from $39.7 billion to $137.3 billion, or per capita spending from $1,715 to $4089.[135] In 2013 the total reached $211 billion, averaging $5,988 per person.[136] Figures in National Health Expenditure Trends, 1975 to 2012, show that the pace of growth is slowing. Modest economic growth and budgetary deficits are having a moderating effect. For the third straight year, growth in healthcare spending will be less than that in the overall economy. The proportion of Canada's gross domestic product will reach 11.6% in 2012 down from 11.7% in 2011 and the all-time high of 11.9% in 2010.[137] Total spending in 2007 was equivalent to 10.1% of the gross domestic product which was slightly above the average for OECD countries, and below the 16.0% of GDP spent in the United States.[138]

Since 1999, 70% of Canada's total health expenditures is from the public sector and 30% from the private sector.[7][8] This was slightly below the OECD average of public health spending in 2009.[139] Public sector funding included most hospital and physician costs with the other 30% primarily paid by individuals through their private or workplace insurance or out-of-pocket.[140] Half of private health expenditure comes from private insurance and the remaining half is supplied by out-of-pocket payments.[7][8]

There is considerable variation across the provinces/territories as to the extent to which such costs as out of hospital prescription medications, assistive devices, physical therapy, long-term care, dental care and ambulance services are covered.[141]

According to a 2001 article in Annals of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, applying a pharmacoeconomic perspective to analyze cost reduction, it has been shown that savings made by individual hospitals result in actual cost increases to the provinces.[143]

Healthcare spending by province

[edit]The planning and funding of most publicly insured health services are the responsibility of provinces and territories. There is a regional variation in health system characteristics.

Healthcare costs per capita vary across Canada with Quebec ($4,891) and British Columbia ($5,254) at the lowest level and Alberta ($6,072) and Newfoundland ($5,970) at the highest.[134]

Total health spending per resident varies from $7,378 in Newfoundland and Labrador to $6,321 in British Columbia. Public drug spending increased by 4.5% in 2016, driven largely by prescriptions for tumor necrosis factor alpha and hepatitis C drugs.[144]

According to a 2003 article by Lightman, "In-kind delivery in Canada is superior to the American market approach in its efficiency of delivery." In the US, 13.6 percent of GNP is used in medical care. By contrast, in Canada, only 9.5 percent of GNP is used on the Medicare system, "in part because there is no profit incentive for private insurers." Lightman also notes that the in-kind delivery system eliminates much of the advertising that is prominent in the US and the low overall administrative costs in the in-kind delivery system. Since there are no means tests and no bad-debt problems for doctors under the Canadian in-kind system, doctors billing and collection costs are reduced to almost zero.[145]

Public opinion

[edit]According to a 2020 survey, 75% of Canadians "were proud of their health-care system."[146]

An August 31, 2020 PBS article comparing the American healthcare system to Canada's, cited the director of the University of Ottawa's Centre for Health Law, Policy and Ethics, Colleen Flood, who said that there was "no perfect health care system", and the "Canadian system is not without flaws." However, Canadians "feel grateful for what they have." At times, the complacency has resulted in Canadians not demanding for "better outcomes for lower costs". She said that, Canadians are "always relieved that at least [our healthcare system] is not the American system."[147]

A 2009 Nanos Research poll found that 86.2% of Canadians "supported or strongly supported" "public solutions" to make Canadian "public health care stronger."[148] According to the survey report, commissioned by the Canadian Healthcare Coalition, there was "compelling evidence" that Canadians "across all demographics" prefer a "public over a for-profit health-care system."[148][149] A Strategic Counsel survey found 91% of Canadians prefer their healthcare system instead of a U.S. style system.[150][151]

A 2009 Harris-Decima poll found 82% of Canadians preferred their healthcare system to the one in the United States.[152]

A 2003 Gallup poll found 57% of Canadians compared to 50% in the UK, and 25% of Americans, were either "very" or "somewhat" satisfied with "the availability of affordable healthcare in the nation". Only 17% of Canadians were "very dissatisfied" compared to 44% of Americans. In 2003, 48% of Americans, 52% of Canadians, and 42% of Britons say they were satisfied.[153]

A 2016 Canadian Institute for Health Information survey found that Canadians wait longer to access health care services than citizens in 11 other countries including France, Germany, the United States and Australia.[154]

In a 2021 Ipsos poll, 71% of Canadians agreed that their health care system is too bureaucratic to respond to the needs of the population.[155]

The 2024 OurCare Initiative Survey found that, in some provinces, 30% of Canadians lacked access to primary care, 63% lacked access to after-hours or weekend care, and that 65% believed they couldn't get a same or next-day appointment when they urgently needed care.[156]

A timeline of significant events in Canadian healthcare

[edit]The Constitution Act, 1867 (formerly called the British North America Act, 1867) did not give either the federal or provincial governments responsibility for healthcare, as it was then a minor concern. However, the Act did give the provinces responsibility for regulating hospitals, and the provinces claimed that their general responsibility for local and private matters encompassed healthcare. The federal government felt that the health of the population fell under the "Peace, order, and good government" part of its responsibilities.[citation needed]

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council ruled that the federal government had the responsibility of protecting the health and well-being of the population,[citation needed] and that the provinces had the responsibility of administering and delivering healthcare.

Before 1966, Veterans Affairs Canada had a large healthcare network, but this was merged into the general system with the creation of Medicare.

In 1975, Health Canada, which was then known as National Health and Welfare, established the National Health Research and Development Program.

In 1977, cost-sharing agreement between the federal and provincial governments, through the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act and extended by the Medical Care Act was discontinued. It was replaced by Established Programs Financing. This gave a bloc transfer to the provinces, giving them more flexibility but also reducing the federal influence on the health system. Almost all government health spending goes through Medicare, but there are several smaller programs.

Provinces developed their own programs, for example, OHIP in Ontario, that are required to meet the general guidelines laid out in the federal Canada Health Act. The federal government directly administers health to groups such as the military, and inmates of federal prisons. They also provide some care to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and veterans, but these groups mostly use the public system.

In 1996, when faced with a large budget shortfall, the Liberal federal government merged the health transfers with the transfers for other social programs into the Canada Health and Social Transfer, and overall funding levels were cut. This placed considerable pressure on the provinces and combined with population aging and the generally high rate of inflation in health costs, has caused problems with the system.

The 2002 Royal Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, also known as the Romanow Report, was published.[5]

The Canadian Health Coalition formed in 2002.[5]

In 2004, the First Ministers came to an agreement with the federal government on a ten-year plan to improve Canada's healthcare.[157] Areas of focus included wait times, home care, primary care reform, national pharmaceuticals strategy, prevention, promotion and public health, aboriginal health, and the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB) at Health Canada.[157]

In 2006, Stephen Harper won the federal election on a "platform that pushed for a mix of public and private health care, provided that health care stays publicly funded and universally accessible".[97]

Healthcare debates in Canada

[edit]Canada has robust debates between those who support the one-tier public healthcare, such as the Canadian Health Coalition, a group that formed following the publication of the Romanov Report in 2002,[5] and a number of pro-privatization organizations, such as the conservative Fraser Institute, that call for a two-tiered healthcare system. American organizations that support privatization of health services, such as the Cato Institute and the Americans for Prosperity[158][159][160] have focused criticism of the Canadian healthcare system on wait times.[161]

Wendell Potter, who had worked for multinational American health insurance company Cigna from 1993 until 2008, told PBS that the American health industry felt threatened by Canada's healthcare system as it "exposed shortcomings in the private U.S. health system and potentially threatened their profits."[147] He said that corporate PR used the tactic of repeating misinformation about the publicly funded Canadian system by focusing on wait times for elective surgeries.[147][162]

As healthcare debate in the United States reached the top of the U.S. domestic policy agenda during the U.S. 2008 presidential race with a combination of "soaring costs" in the healthcare system and an increasing number of Americans without health insurance because of job loss during the recession, the long wait lists of Canada's so-called "socialized" healthcare system[163] became a key Republican argument against Obama's health reforms.[163] The Huffington Post described it as the "American politics of Canadian healthcare."[164] A 2009 Huffington Post article described how American insurance companies were concerned that they would not be as profitable if his healthcare reforms were implemented.[165]

Starting in July 2009, Canadian Shona Holmes of Waterdown, Ontario became the poster child of the Americans for Prosperity support for Republican presidential candidates against then-candidate and President Barack Obama's who ran on health reform and the Affordable Care Act.[158][159][166][160] In 2005, Holmes had paid $100,000 out-of-pocket for immediate treatment for a condition called Rathke's cleft cyst at the U.S. Mayo Clinic, one of the best hospitals in the world,[167] the Singapore General Hospital, and the Charité hospital in Berlin[167] instead of waiting for an appointment with specialists in her home province of Ontario.[168][169] In 2007, she filed a lawsuit against the Ontario government when OHIP refused to re-imburse her $100,000. The media attention from the Americans for Prosperity advertisements resulted in further scrutiny of Holmes' story. A 2009 CBC report consulted medical experts who found discrepancies in her story, including that Rathke's cleft cyst was neither cancerous or life-threatening.[170] The mortality rate for patients with a Rathke's cleft cyst is zero percent.[171]

Since 1990, the Fraser Institute has focused on investigating the Canadian healthcare system's historic and problematic wait times by publishing an annual report based on a nationwide survey of physicians and health care practitioners, entitled Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada. The 2021 edition of the report found that the average waiting time between referral from a general practitioner and delivery of elective treatment by a specialist rose from 9.3 weeks in 1993 to 25.6 weeks in 2021.[172] Waiting times ranged from a low of 18.5 weeks in Ontario to 53.2 weeks in Nova Scotia.

A 2015 Fraser Institute article focused on Canadians who sought healthcare in other countries and reported that the percentage of Canadian patients who travelled abroad to receive non-emergency medical care was 1.1% in 2014, and 0.9% in 2013, with British Columbia being the province with the highest proportion of its citizens making such trips.[173] A 2017 Fraser Institute cost-effectiveness analysis promoted a two-tiered system with more privatization, arguing that "although Canada ranks among the most expensive universal-access health-care systems in the OECD, its performance for availability and access to resources is generally below that of the average OECD country, while its performance for use of resources and quality and clinical performance is mixed."[174][161]

Flaws in Canada's healthcare system

[edit]Identified weaknesses of Canada's system were comparatively higher infant mortality rate, the prevalence of chronic conditions, long wait times, poor availability of after-hours care, and a lack of prescription drugs coverage.[175] Limited dental coverage was added in 2023 [176][16] An increasing problem in Canada's health system is a shortage of healthcare professionals and hospital capacity.[18]

Prescription medications have been consistently expensive in Canada, which has the third-highest drug costs of any OECD nation,[177] and a 2018 study found that almost 1 million Canadians gave up food or heat to afford prescription medications.[178][179] In 2021, over one in five (21%) adults in Canada reported not having any prescription insurance to cover medication costs.[180]

There is enormous waste in Canada's healthcare system related to medical records. Although the Canadian federal government has invested more than $2.1 billion developing health information technology (HIT), all 10 provinces still have their own separate incompatible HIT systems.[181] A recent study[182] showed that a shift to shared open source medical software could save Canada's healthcare system millions of dollars.[183]

Hospital and urgent care access

[edit]Canada's hospital beds per capita have decreased 63% since 1976,[184] to 44% fewer beds than the OECD average.[185][186] Overcrowding, or "hallway medicine," is common in hospitals,[187] and hospital patients are instructed to sleep on concrete floors,[188] in storage rooms,[189] as hospitals often operate at over 100% capacity,[190] and in some regions as high as 200%[191] capacity.[192] In 2023, more than 1.3 million Canadians "gave up" waiting for emergency care, and left without being seen.[193] The crisis is projected to continue to build, as Canada's hospitals are unable to operate safely at 90% or greater ongoing capacity.[194]

In addition, ambulance access in Canada is also inconsistent[195] and decreasing,[196][197][198][199] with Code/Level Zeros, where one or no ambulances are available for emergency calls, doubling and triple year-over-year in major cities such as Calgary,[200] Ottawa,[201][202] Windsor, and Hamilton.[203][204] As an example, cumulatively, Ottawa spent seven weeks lacking ambulance response abilities, with individual periods lasting as long as 15 hours, and a six-hour ambulance response time in one case.[205][206] Ambulance unload delays, due to hospitals lacking capacity[207] and cutting their hours,[208] have been linked to deaths,[209] but the full impact is unknown as provincial authorities, have not responded to requests to release ambulance offload data to the public.[210]

Plans to address ambulance access that included using taxis instead of ambulances[211] to transport patients have drawn support from local leaders,[212] but rejection from local residents[213] and Ontario's provincial authorities.[210]

“That kind of creative solution is exactly what we need. I was a little bit surprised that the province wasn’t in agreement with that option,”

— Mark Sutcliffe, Mayor of Ottawa

Temporary hospital and emergency room closures are common[214][215][216][217][218][219][220] in Canada, with over 1,100 in Ontario alone in 2023,[221] and in 2022, the president of the Canadian Medical Association described Canada's healthcare system with the following quote;[222]

"We've been saying for a while that we're concerned about collapse. And in some places, collapse has already happened,"

— Dr. Alika Lafontaine, President of the Canadian Medical Association

Canada's healthcare system ranks poorly among peer nations on medical technology access indicators, ranking second-to-last in the G20 for MRI units[223] and radiotherapy equipment,[224] fifth-to-last for CT scanners,[225] and has 33% fewer mammography machines than the G20 average.[226]

Wait times

[edit]In a May 28, 2020, report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that examined wait times in member nations—all of which are democratic countries with high-income economies with a very high Human Development Index (HDI), found that long waiting times for health services was an important policy issue in most OECD countries.[227] In 2017, Canada ranked above the average on OECD indicators for wait-times and access to care, with average scores for quality of care and use of resources.[15]

In the 1980s and the 1990s, wait times for certain surgeries, such as knee and hip replacements, had increased.[228][229] The year before the 2002 Romanow Royal Commission report was released, in 2001, the Ontario Health Coalition (OHC) called for increased provincial and federal funding for Medicare and an end to provincial funding cuts as solutions to unacceptable wait times.[230]

In December 2002, the Romanow Report recommended that "provincial and territorial governments should take immediate action to manage wait lists more effectively by implementing centralized approaches, setting standardized criteria, and providing clear information to patients on how long they can expect to wait."[5] In response to the report, in September 2004, the federal government came to an agreement with the provinces and territories add an additional C$41 billion over a ten-year period, to the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) to improve wait times for access to essential services, a challenge that most other OECD countries shared at that time. By 2006, the federal government had invested C$5.5 billion to decrease wait times.[231]

In April 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper promised that all ten provinces and three territories would establish wait-time guarantees by 2010. [232]

In 2015, Choosing Wisely Canada promoted evidence-based medicine in 2015.[233] Organizations like this focus on facilitating doctor-patient communication to decrease unnecessary care in Canada and to decrease wait times.[234]

In 2014, wait times for knee replacements were much longer in Nova Scotia,[235] compared to Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland.[citation needed]

A 2016 study by the Commonwealth Fund, based in the US, found that Canada's wait time for all categories of services ranked either at the bottom or second to the bottom of the 11 surveyed countries (Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States). Canada's wait time on emergency services was the longest of the 11 nations, with 29% of Canadians reporting that they waited for more than four hours the last time they went to an emergency department. Canada also had the longest wait time for specialist appointments, with 56% of all Canadians waiting for more than four weeks. Canada ranked last in all other wait time categories, including same- or next-day appointments, same-day answers from doctors, and elective surgeries, except for access to after-hour care, where Sweden ranks lower. The 2016 study also noted that despite government investment, Canada's wait-time improvements were negligible when compared to the 2010 survey.[236]

The 2021 Waiting Your Turn: Wait Times for Health Care in Canada report by the Fraser Institute found that the average waiting time between referral from a general practitioner and delivery of elective treatment by a specialist rose from 9.3 weeks in 1993 to 25.6 weeks in 2021.[172] Waiting times ranged from a low of 18.5 weeks in Ontario to 53.2 weeks in Nova Scotia.

Gender gaps in healthcare

[edit]

Gender gaps in healthcare are significantly influenced by socioeconomic status, geographical location, and ethnicity.[237] It has been hypothesized that women experience a higher rate of health-related issues because of their reduced access to the material and social conditions of life that foster good health, as well as a heightened level of stress associated with their gender and marital roles.[238] Moreover, research has shown that women with low income and who work full-time outside of the house have poorer health status in comparison to their male counterparts.[239][citation needed] The added responsibilities women hold as primary caregivers in households not only creates additional stress, but also indirectly increases the difficulty of the scheduling and meeting of medical appointments; these implications explain women's poorer self-rated health status in comparison to men, as well as their report of their unmet healthcare needs.[239][citation needed]

Women's additional healthcare requirements, such as pregnancy, further exacerbate the gender gap. Despite comprising approximately half of Canada's population, women receive the majority of Canadian healthcare.[240]

Men and women also experience different wait times for diagnostic tests; longer wait times have been associated with a higher risk of health complications. One Canadian study reports, "mean wait times are significantly lower for men than for women pertaining to overall diagnostic tests: for MRI, 70.3 days for women compared to 29.1 days for men."[241]

Effects of healthcare privatization

[edit]Disparities between men and women's access to healthcare in Canada have led to criticism, especially regarding healthcare privatization. While most healthcare expenses remain covered by Medicare, certain medical services previously paid for publicly have been shifted to individuals and employer-based supplemental insurance. While this shift has affected both genders, women have been more affected. Compared to men, women are generally less financially stable, and individual payments are a greater burden.[240] Furthermore, many women work part-time or in fields that do not offer supplemental insurance, such as homemaking. As such, women are less likely to have private insurance to cover the costs of drugs and healthcare services.[242]

The shift from public to private financing has also meant additional labor for women due to families relying on them as caregivers. Less public financing has shifted care to women, leaving "them with more support to provide at home."[243]

Women's additional healthcare requirements, such as pregnancy, further exacerbate the gender gap. Despite comprising approximately half of Canada's population, women receive the majority of Canadian healthcare.[240]

Socioeconomic gap in healthcare

[edit]It has been previously documented that one's socioeconomic status significantly impacts their health.[244][245] Another recent study re-assessed this relationship and found similar results that demonstrated that people with higher levels of education or income experience longer life expectancies and health-adjusted life expectancies.[246] The study discovered a distinct stepwise gradient in Canada, with life expectancy and health-adjusted life expectancy incrementally increasing as social position improves.[246] They also found that this socioeconomic gap in healthcare had gotten wider in the previous 15 years.[246]

The reasoning behind the socioeconomic gap is complex and multifaceted.[247] Certain relationships between socioeconomic status and health outcomes can be relatively easily explained through direct exposures.[247] For example, lead or pollutant exposure tends to be more common in rural neighbourhoods, which can result in lower cognitive functions, stunted growth and exacerbated asthma.[248][249] Higher income levels allow for the purchase of higher-quality resources, including food products, produce and shelter, as well as faster access to services.[250] Higher education is often thought to lead to greater health literacy, resulting in the adoption of healthier lifestyles.[251]

Longer, more complex pathways can also be used to explain potential relationships between socioeconomic status and health outcomes. Duration of poverty has been related to increased chronic stress levels.[252] Recent studies have described how these stress levels can result in the biological "wear-and-tear" for these individuals constantly exposed to social and environmental stressors.[253] Increased stress and lower SES has been correlated with increased blood pressure, worser cholesterol profiles and increased risk for other cardiovascular diseases.[254]

Inequalities in care by community

[edit]Black community

[edit]In Canadian healthcare, Black individuals encounter pervasive discrimination from overt acts like harassment to subtle daily indignities, eroding trust and discouraging Black Canadians from seeking medical care.[255][256] A quantitative study in the Greater Toronto Area found that all 24 Black women participants experienced objectification, maltreatment, and unequal power dynamics in healthcare, mirroring historical patterns of oppression and exposing racial treatment disparities amid challenging healthcare access.[257]

Black Canadians encounter significant racial treatment disparities, including lower rates of receiving biologic treatments such as medications for rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, compared to White patients.[258] Additionally, limited participatory visits with physicians and clinical trials, undermining treatment validation.[259] Despite Canada's universal healthcare access, socioeconomic status exacerbates these disparities, hindering low-income individuals' access to prescription drug coverage and specialist care.[259] Evidently, racialized persons are twice as likely as non-racialized persons to face these challenges.[259] These issues are further compounded by historical and systemic contexts and a lack of diversity among healthcare workers, shaping negative healthcare experiences for Black individuals.[259]

In contemporary Canadian healthcare, research indicates that everyday racism adversely affects the health outcomes of Black Canadians and other racialized communities.[260] For instance, in Ontario, Black people, constituting 5% of the population, represented one-quarter of new HIV diagnoses.[261] Additionally, throughout the first 14 months of the COVID-19 epidemic in Toronto, Black people accounted for 14% of cases and 15% of hospitalizations, despite comprising 9% of the city's population.[262] These findings highlight that Black Canadians face insensitivity and discrimination from healthcare providers, dissuading individuals from seeking care and exacerbating disparities in health outcomes.

Studies highlight that evidence-informed health promotion initiatives and interventions targeting racism's impact on health and within Canadian healthcare are crucial for promoting health equity, rebuilding trust within the healthcare system, and improving public health outcomes in Canada.[263] Additionally, collecting ethically disaggregated ethno-racial data for monitoring outcomes is essential for positive changes within the Canadian healthcare system.[264]

Indigenous community

[edit]It is well documented in the literature that Indigenous peoples in Canada lack equitable access to healthcare services for a variety of reasons.[265] One major reason for this inequitable access is due to Indigenous locations of residence. Statistics Canada reported that the majority of Métis live in urban centres, while almost half of First Nations people live on reserves.[266] In rural northern communities, they struggle to attract and retain healthcare professionals, leaving a great shortage in services that results in far lesser access to care.[267] In the Inuit Nunangat, it was found that just 23% of Inuit had a medical doctor they regularly visited.[268] Additionally, due to the lack of healthcare access in northern communities, many are forced into lengthy transportation to southern Ontario to receive necessary care. One study examined an Inuit community in Rigolet, Canada, and looked at the direct and indirect costs of these long-distance healthcare visits, including missed paid employment, mental well-being costs, transportation costs and others. Altogether, this community experiences healthcare costs greater than other Canadian non-Indigenous and urban areas.[269]

Another prominent reason for inequitable access to care is the persistence of racism that remains in Canada.[270] In 2012, The Health Council of Canada conducted a series of meetings across the country with a variety of healthcare workers, researchers and Aboriginal people. Through their conversations, they discovered that a large part of the problem comes from the healthcare system. They found that many Indigenous people simply do not trust mainstream health service due to stereotyping, racism and that they feel intimidated. One participant described their experiences as "being treated with contempt, judged, ignored, stereotyped, racialized, and minimized." Finally the Health Council of Canada went on to describe that this lack of equitable access comes as an extension of systemic racism in Canada.[270]

A 2015 study examined 80 Indigenous women who experienced neurological conditions.[271] Participants described their lack of access to health services to stem from the racism and sexism experienced in the system. In the same study, the researchers interviewed multiple key informants, including various types of health practitioners. They described how important it is for the health system to implement culturally safe care. They also discussed how many stereotyping problems occur in medical school and that Canada requires further Indigenous-centred training. They recommend higher education and awareness training amongst medical schools and healthcare institutions to address the growing healthcare disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.[271]

LGBT community

[edit]Canadians in the LGBT community, especially those in poverty, receive inadequate levels of treatment. A research study by Lori Ross and Margaret Gibson notes that of all demographics, LGBT members need mental health services the most due to systemic discrimination. According to the study, LGBT members often need to turn to mental health services that are mainly private and not covered by publicly funded healthcare. Low-income LGBT members might be unable to afford these private programs; subsequently, their mental health issues may remain unaddressed or even worsen.[272]

Researcher Emily Colpitts states that LGBT members in Nova Scotia experience ambiguous or alienating language in their health policies. According to Colpitts, the "heteronormative and gender-binary language and structure of medical intake forms have the consequence of alienating LGBT populations." Colpitts adds that in the previous study of queer and transgender women in Nova Scotia, patients experienced significant discomfort in their meetings with healthcare providers and feared that because of the language of health policy, they would not be able to receive adequate healthcare based on their sexual identities.[273]

According to researcher Judith MacDonnell, LGBT members, especially childbearing lesbians, have trouble navigating through health policy. MacDonnell states that LGBT women encounter challenges at every point of the childbearing process in Canada and have to rely on personal and professional means to receive information that they can understand, such as in reproductive health clinics and postpartum or parenting support.[274]

The healthcare needs of the LGBT community are affected by a number of social, behavioural, and structural factors.[275] Various bodies of literature have identified the health disparities associated with the LGBT community, and how these individuals receive disproportionate healthcare services. For example, mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety, eating disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases are all of higher prevalence and a major concern amongst LGBT persons.[275] These health issues are not sufficiently addressed either, as healthcare professionals (such as physicians) may be unaware of these individuals' sexual orientation. In 2008, Analysis of Canadian Community Health Service data showed that: LGB persons were more likely to seek out mental health services than heterosexuals;[276] lesbians have lower reported rates of using family physicians.[276] bisexuals report higher levels of unmet healthcare needs compared to heterosexuals(2); and LGB persons perceive they have less equitable access to healthcare services compared to heterosexual persons.[277]

Another barrier that exists with regard to the healthcare disparities experienced by LGBT persons is the stigma that continues to persist in society. Moreover, LGBT populations may fear that their health needs are not considered in primary health since healthcare has been historically been constituted through a cisnormative and heteronormative framework.[278] As a result, LGBT populations are less likely to access primary healthcare services due to the fear of discrimination.[278] In addition, recent data shows that healthcare professionals lack adequate knowledge and cultural competence when it comes to addressing health issues predominantly affecting the LGBT community.[279] Cultural competence is an important consideration in assessing the quality of care received by the LGBT community, as a lack of cultural competency in healthcare professionals and systems leads to a reduced life expectancy, a lower quality of life, and an increased risk of acute and chronic illness amongst LGBT persons.[278] Research has also highlighted that higher rates of chronic illness seen in LGBT persons is associated with discrimination, minority stress, avoidance of healthcare providers, and irregular access to healthcare services.[280]

Another important consideration in addressing the quality of care received by the LGBT community is patient-physician communication.[281] Many health risks LGBT persons face come as a result of avoidance and/or dissatisfaction of healthcare services; this is in part due to assumptions made by the patient's healthcare providers, such as assuming the sexuality of the patient and predicting their sexual behaviours.[281] In these scenarios, it can be very difficult for LGBT persons to feel comfortable in a clinical setting because they may experience a decline in self-confidence and trust in their healthcare providers.

The underlying message in terms of providing equitable care, and access to care, for patients in the LGBT community is that healthcare providers and systems must be aware of the appropriate methods through which to administer care. The specific needs of LGBT persons must be appreciated in order to enhance the quality of care and provide it in a non-judgemental, gender-neutral manner.[281]

Immigrants