Central Arizona Project

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2012) |

Central Arizona Project | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 34°17′10″N 114°06′13″W / 34.28611°N 114.10361°W |

| Begins | Lake Havasu, La Paz County |

| Ends | Pima Mine Road, Pima County |

| Owner | United States Bureau of Reclamation |

| Maintained by | Central Arizona Water Conservation District |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 336 mi (541 km) |

| Capacity | 456 billion gallons (1.4 million acre feet) per year |

| History | |

| Construction start | 1973 |

| Opened | 1993 |

| Location | |

| |

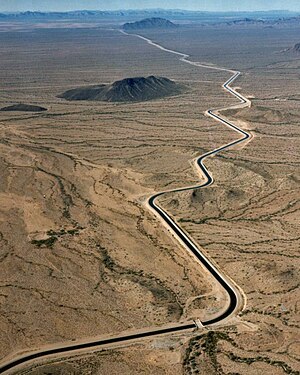

The Central Arizona Project (CAP) is a 336 mi (541 km) diversion canal in Arizona in the southern United States.

The aqueduct diverts water from the Colorado River at the Bill Williams Wildlife Refuge south portion of Lake Havasu near Parker into central and southern Arizona. CAP is managed and operated by the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD).[1] It was shepherded through Congress by Carl Hayden.[2]

Description

[edit]

The CAP delivers Colorado River water, either directly or by exchange, into central and Southern Arizona. The project was envisioned to provide water to nearly one million acres (405,000 hectares) of irrigated agricultural land areas in Maricopa, Pinal, and Pima counties, as well as municipal water for several Arizona communities, including the metropolitan areas of Phoenix and Tucson. Authorization also was included for development of facilities to deliver water to Catron, Hidalgo, and Grant counties in New Mexico, but these facilities have not been constructed because of cost considerations, a lack of demand for the water, lack of repayment capability by the users, and environmental constraints.

In addition to its water supply benefits, the project also provides substantial benefits from flood control, outdoor recreation, fish and wildlife conservation, and sediment control. It also produces an unintended swale, further increasing local biodiversity. The project was subdivided, for administration and construction purposes, into the Granite Reef, Orme, Salt-Gila, Gila River, Tucson, Indian Distribution, and Colorado River divisions. During project construction, the Orme Division was reformulated and renamed the Regulatory Storage Division. Upon completion, the Granite Reef Division was renamed the Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct, and the Salt-Gila Division was renamed the Fannin-McFarland Aqueduct.

The 456 billion gallons (1.4 million acre feet) of water is lifted by up to 2,900 feet by 14 pumps using 2.5 million MWh of electricity each year [285 MW], making CAP the largest power user in Arizona. Lake Pleasant is used as a buffer.[3][4]

The canal loses approximately 16,000 acre-feet (5.2 billion gallons) of water each year to evaporation. It loses 9,000 acre-feet (2.9 billion gallons) annually from water seeping or leaking through the concrete.[5]

History

[edit]

The CAP was created by the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968, signed by US President Lyndon B. Johnson on September 30, 1968.[6][7] Senator Ernest McFarland, along with Senator Carl Hayden, lobbied for the Central Arizona Project (CAP) aimed at providing Arizona's share of the Colorado River to the state. McFarland's efforts failed as senator; however, they laid a critical foundation for the eventual passage of the CAP in the late 1960s.

According to the Arizona Republic, Senator Barry Goldwater, Senator Hayden, Representative Morris Udall, US Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall and other Arizona leaders teamed up on the successful passage of what was McFarland's intended legislation that became the CAP, "probably the state's most celebrated bipartisan achievement of the 20th century."[8] This act provided for the US Secretary of the Interior to enter into an agreement with non-federal interests, whereby the US federal government acquired the right to 24.3 percent of the power produced at the non-federal Navajo Generating Station, Navajo Project. The agreement also includes the delivery of power and energy over the transmission facilities to delivery points within the Central Arizona Project service area.[citation needed]

Construction of the project began in 1973 with the award of a contract for the Havasu Intake Channel Dike and excavation for the Havasu Pumping Plant (later renamed as the Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant) on the shores of Lake Havasu. Construction of the other project features, such as the New Waddell Dam, followed. The backbone aqueduct system, which runs about 336 miles (541 km) from Lake Havasu to a terminus 14 miles (23 km) southwest of Tucson, was declared substantially complete in 1993. The new and modified dams constructed as part of the project were declared substantially complete in 1994. All of the non-Native American agricultural water distribution systems were completed in the late 1980s, as were most of the municipal water delivery systems. Several Native American distribution systems remain to be built; it is estimated that full development of these systems could require another 10 to 20 years.[when?]

The Hayden-Rhodes Aqueduct, which carries water from Lake Havasu to the Phoenix area, includes three tunnels totaling 8.2 miles.[9]

The CAP partly funded the Brock Reservoir project with $28.6 million. In return for its contribution, Arizona has been awarded 100,000 acre-feet (120,000,000 m3) of water per year since 2016.[citation needed]

The CAP project brought river water to Tucson successfully, but the initial implementation was called a "debacle" by the Tucson Weekly.[10] The river water had a different mineral mixture and flow pattern from the aquifer water, stirring up and dislodging rust and biofilm[11] in municipal water mains and house pipes.[12]

By the end of 1993, the city of Tucson paid about $145,000 to install filters in 925 homes, lost about $200,000 in revenues by adjusting water bills, and paid about $450,000 in damages claimed by homeowners for ruined pipes, water heaters, and other appliances.[13] The city returned some houses to groundwater, but problems remained. Zinc orthophosphate was added to coat the pipes and prevent the rust from dislodging, but the return to groundwater removed the zinc orthophosphate.[14] The solution was a US Environmental Protection Agency-funded "blended" water system, including automatically monitoring water quality throughout Tucson, and a website to report the water quality to the public without intervention by the Tucson Water Department.[15][16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Central Arizona Project". Central Arizona Project. Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- ^ Jack L. August Jr., Vision in the Desert: Carl Hayden and Hydropolitics in the American Southwest (1999). p. 69 [ISBN missing]

- ^ "CAP Power Fact Sheet" (PDF). CAP. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2020.

- ^ Walter, Nick (August 18, 2020). "As summertime CAP water deliveries rise, power usage plummets – Central Arizona Project". CAP. Archived from the original on January 23, 2021.

- ^ "As Temperatures Rise, Arizona Sinks". High Country News. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- ^ "September (1968)". Lyndon B. Johnson Centennial Celebration. Archived from the original on 2010-01-31. Retrieved 2012-07-24.

- ^ "Morris Udall Papers – Central Arizona Project". University of Arizona Library – Special Collections. Archived from the original on 2016-04-01. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ^ Nowicki, Dan (2009-01-01), "What's happened to GOP since Goldwater", Arizona Republic, retrieved 2010-05-12

- ^ "Central Arizona Project". Bureau Of Reclamation. Bureau Of Reclamation. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ^ Vanderpool, Tim. "Hard Water Decision (October 2006)". Tucson Weekly. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ McGuire, Michael. "The Role of Water Treatment in the Tucson Colored Water Crisis (September 2018)". American Water Works Association. Retrieved 2024-08-15.

- ^ Marj Pettis (December 28, 1993). "Panel judges CAP water harmless, despite controversy". The Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ Enric Volante (December 20, 1993). "City may offer grants to fix CAP damage; Officials propose $1 million for repairs to older homes". The Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ Enric Volante (November 11, 1993). "Switch from CAP hasn't yet solved problem with rust". The Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ "Tucson's EMPACT Grant". City of Tucson. Archived from the original on 2011-11-05. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ^ "What is My Water Quality?". City of Tucson Water Department. Archived from the original on 2015-05-05. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

Further reading

[edit]- August Jr., Jack L. "Water, Politics, and the Arizona Dream: Carl Hayden and the Modern Origins of the Central Arizona Project, 1922–1963", Journal of Arizona History (1999) 40#4 pp. 391–414

External links

[edit]- Aqueducts in the United States

- Buildings and structures in Maricopa County, Arizona

- Canals in Arizona

- Colorado River

- Buildings and structures in La Paz County, Arizona

- Buildings and structures in Pinal County, Arizona

- Buildings and structures in Pima County, Arizona

- Buildings and structures in Mohave County, Arizona

- 1968 establishments in Arizona

- Interbasin transfer