Harry Potter (film series)

| Harry Potter | |

|---|---|

Harry Potter logo as used in the films | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by | Steve Kloves (1–4, 6–8) Michael Goldenberg (5) |

| Based on | Harry Potter by J. K. Rowling |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date | 2001–2011 |

Running time | 1,179 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | Total (8 films) $1.2 billion |

| Box office | Total (8 films) $7.7 billion |

Harry Potter is a film series based on the Harry Potter series of novels by J. K. Rowling. The series was produced and distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures and consists of eight fantasy films, beginning with Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001) and culminating with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011).[2][3] A spin-off prequel series started with Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (2016), marking the beginning of the Wizarding World shared media franchise.[4]

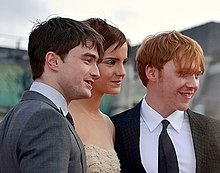

The series was mainly produced by David Heyman, and stars Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson as the three leading characters: Harry Potter, Ron Weasley, and Hermione Granger. Four directors worked on the series: Chris Columbus, Alfonso Cuarón, Mike Newell, and David Yates.[5] Michael Goldenberg wrote the screenplay for Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), while the remaining films' screenplays were written by Steve Kloves. Production took place over ten years, with the main story arc following Harry's quest to overcome his arch-enemy Lord Voldemort.[6]

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, the seventh and final novel in the series, was adapted into two feature-length parts.[7] Part 1 was released in November 2010, and Part 2 was released in July 2011.[8][9]

Deathly Hallows – Part 2 is among the 50 highest-grossing films of all time—at 18th-highest, grossing over $1 billion. It is the fourth-highest-grossing film series, with $7.7 billion in worldwide receipts.

Origins

In late 1997, film producer David Heyman's London offices received a copy of the first book in what would become Rowling's series of seven Harry Potter novels. The book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was relegated to a low-priority bookshelf, where it was discovered by a secretary who read it and gave it to Heyman with a positive review. Consequently, Heyman, who had originally disliked "the rubbish title", read the book himself. Highly impressed by Rowling's work, he began the process that led to one of the most successful cinematic franchises of all time.[10]

Heyman's enthusiasm led to Rowling's 1999 sale of the film rights for the first four Harry Potter books to Warner Bros. for a reported £1 million (US$2,000,000).[11] A demand Rowling made was that the principal cast be kept strictly British and Irish wherever possible, such as Richard Harris as Dumbledore, allowing nonetheless for casting of French and Eastern European actors in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire where characters from the book are specified as such.[12] Rowling was hesitant to sell the rights because she "didn't want to give them control over the rest of the story" by selling the rights to the characters, which would have enabled Warner Bros. to make non-author-written sequels.[13]

Although Steven Spielberg initially negotiated to direct the first film, he declined the offer.[14] Spielberg contended that, in his opinion, there was every expectation of profit in making the film. He claims that making money would have been like "shooting ducks in a barrel. It's just a slam dunk. It's just like withdrawing a billion dollars and putting it into your personal bank accounts. There's no challenge."[15] In the "Rubbish Bin" section of her website, Rowling maintains that she had no role in choosing directors for the films, writing "Anyone who thinks I could (or would) have 'veto-ed' him [Spielberg] needs their Quick-Quotes Quill serviced."[16]

After Spielberg left, conversations began with other directors, including Chris Columbus, Jonathan Demme, Terry Gilliam, Mike Newell, Alan Parker, Wolfgang Petersen, Rob Reiner, Tim Robbins, Brad Silberling, and Peter Weir.[17] Petersen and Reiner both pulled out of the running in March 2000.[18] It was then narrowed down to Columbus, Gilliam, Parker, and Silberling.[19] Rowling's first choice was Gilliam.[20] However, on 28 March 2000, Columbus was appointed as director of the film, with Warner Bros. citing his work on other family films such as Home Alone and Mrs. Doubtfire as influences for their decision.[21]

Harry Potter is the kind of timeless literary achievement that comes around once in a lifetime. Since the books have generated such a passionate following across the world, it was important to us to find a director that has an affinity for both children and magic. I can't think of anyone more ideally suited for this job than Chris [Columbus].

Steve Kloves was selected to write the screenplay for the first film. He described adapting the book as "tough" since it did not "lend itself to adaptation as well as the next two books". Kloves was sent a "raft" of synopses of books proposed as film adaptations, with Harry Potter being the only one that jumped out at him. He went out and bought the book, becoming an instant fan. When speaking to Warner Bros. he stated that the film had to be British and true to the characters.[22] David Heyman was confirmed to produce the film.[21] Rowling received a large amount of creative control for the film, an arrangement that Columbus did not mind.[23]

Warner Bros. had initially planned to release the first film over the 4 July 2001 weekend, making for such a short production window that several of the originally proposed directors had withdrawn themselves from contention. Eventually, due to time constraints, the date was put back to 16 November 2001.[24]

Casting the roles of Harry, Ron, and Hermione

In 2000, after a seven-month search, lead actor Daniel Radcliffe was discovered by producer David Heyman and writer Steve Kloves seated just behind them in a theatre. In Heyman's own words, "There sitting behind me was this boy with these big blue eyes. It was Dan Radcliffe. I remember my first impressions: He was curious and funny and so energetic. There was real generosity too, and sweetness. But at the same time he was really voracious and with hunger for knowledge of whatever kind."[10]

Radcliffe had already established himself as an actor in the 1999 BBC television production of David Copperfield in which he played the title role's childhood years. Heyman persuaded Radcliffe's parents to allow him to audition for the part of Harry Potter, which involved Radcliffe being filmed.[10][n 1] Rowling was enthusiastic after viewing Radcliffe's filmed test, saying she didn't think there was a better choice for the part of Harry Potter.[10][26]

Also in 2000, the then-unknown British actors Emma Watson and Rupert Grint were selected from thousands of auditioning children to play the roles of Hermione Granger and Ron Weasley, respectively. Their only previous acting experience was in school plays. Grint was eleven years old and Watson ten at the time they were cast.[27]

Los Angeles Times writer Geoff Boucher, who conducted the above-mentioned interview with Heyman, added that the casting of the three major roles "is especially impressive in hindsight. The trio's selection was arguably one of the best show-business decisions over the past decade ... they have shown admirable grace and steadiness in the face of teen superstardom."[10][26]

Production

Filming for the series began at Leavesden Studios, Hertfordshire, England, in September 2000 and ended in December 2010, with post-production on the final film lasting until summer 2011.[6] Leavesden Studios was the main base for filming Harry Potter, and it opened to the public as a studio tour in 2012 (renamed as Warner Bros. Studios, Leavesden).[28]

David Heyman produced all the films in the series with his production company Heyday Films, while David Barron joined the series as an executive producer on Chamber of Secrets and Goblet of Fire. Barron was later appointed producer on the last four films. Chris Columbus was an executive producer on the first two films alongside Mark Radcliffe and Michael Barnathan, but he became a producer on the third film alongside Heyman and Radcliffe. Other executive producers include Tanya Seghatchian and Lionel Wigram. J. K. Rowling, author of the series, was asked to become a producer on Goblet of Fire but declined. She subsequently accepted the role on the two-part Deathly Hallows.[29]

Heyday Films and Columbus' company 1492 Pictures collaborated with Duncan Henderson Productions in 2001, Miracle Productions in 2002, and P of A Productions in 2004. Even though Prisoner of Azkaban was the final film produced by 1492 Pictures, Heyday Films continued with the franchise and collaborated with Patalex IV Productions in 2005. The sixth film in the series, Half-Blood Prince, was the most expensive film to produce as of 2009[update].

Warner Bros. adapted the seventh and final novel in the series, Deathly Hallows, into two cinematic parts. The two parts were filmed back-to-back from early 2009 to summer 2010, with the completion of reshoots taking place on 21 December 2010; this marked the end of filming Harry Potter. Heyman stated that Deathly Hallows was "shot as one film" but released in two feature-length parts.[30]

Tim Burke, the visual effects supervisor of the series, said of the production on Harry Potter, "It was this huge family; I think there were over 700 people working at Leavesden, an industry in itself." David Heyman said, "When the first film opened, no way did I think we'd make eight films. That didn't seem feasible until after we'd done the fourth." Nisha Parti, the production consultant on the first film, said that Heyman "made the first film very much the way he felt the studio Warner Bros. wanted to make it". After the film's success, Heyman was given "more freedom".[31]

One of the aims of the filmmakers from the beginning of production was to develop the maturity of the films. Chris Columbus stated, "We realised that these movies would get progressively darker. Again, we didn't know how dark but we realised that as the kids get older, the movies get a little edgier and darker."[32] This transpired with the succeeding three directors who would work on the series in the following years, with the films beginning to deal with issues such as death, betrayal, prejudice, and political corruption as the series developed narratively and thematically.[5][33]

Directors

After Chris Columbus had finished working on Philosopher's Stone, he was hired to direct Chamber of Secrets. The production started within a week after the release of the first film. Columbus was set to direct all entries in the series,[34] but he did not want to return for Prisoner of Azkaban, claiming he was "burned out".[35] He moved to the position of producer, while Alfonso Cuarón was approached for the role of director. He was initially nervous about directing the instalment since he had not read any of the books or seen the films. After reading the series, he changed his mind and signed on to direct since he had immediately connected to the story.[36]

Because Cuarón decided not to direct the fourth instalment, Goblet of Fire, a new director had to be selected.[37] Mike Newell was chosen to direct the film, but he declined to do so for the next film, Order of the Phoenix, which was given to David Yates, who also directed Half-Blood Prince and both parts of Deathly Hallows, becoming the only director to helm more than one film since Columbus.

Columbus said his vision for the first two films was of a "golden storybook, an old-fashioned look", while Cuarón changed the visual tone of the series, desaturated the colour palette, and expanded the landscape around Hogwarts.[32][37] Newell decided to direct the fourth film as a "paranoid thriller", while Yates wanted to "bring a sense of jeopardy and character to the world".[38][39] Cuarón, Newell, and Yates have said that their challenge was striking a balance between making the films according to their individual vision, while working within a cinematic world already established by Columbus.[37][38][39]

Heyman commented on the "generosity of the directors" by revealing that "Chris spent time with Alfonso, Alfonso spent time with Mike and Mike spent time with David, showing him an early cut of the film, talking through what it means to be a director and how they went about [making the films]."[40] He also said, "I suppose Chris Columbus was the most conservative choice from the studio's point of view. But he expressed real passion."[31] Producer Tanya Seghatchian said they were "more adventurous" in choosing a director for the third film and went straight to Cuarón.[31] Newell became the first British director of the series when he was chosen for the fourth film; Newell was considered to direct the first film before he dropped out.[31] Yates directed the final films after Heyman thought him capable of handling the edgy, emotional, and political material of the later novels.[41]

All the directors have been supportive of each other. Columbus praised the character development in the films, while Cuarón admired the "quiet poetry" of Yates' films.[32][37] Mike Newell noted that each director had a different heroism, and Yates views the first four films "respectfully and enjoy[s] them".[38][39] Radcliffe said Yates "took the charm of the films that Chris made and the visual flair of everything that Alfonso did and the thoroughly British, bombastic nature of the film directed by Mike Newell" and added "his own sense" of realism.[42]

Scripts

Steve Kloves wrote the screenplays for all but the fifth film, which was penned by Michael Goldenberg. Kloves had direct assistance from J.K. Rowling, though she allowed him what he described as "tremendous elbow room". Rowling asked Kloves to remain faithful to the spirit of the books; thus, the plot and tone of each film and its corresponding book are virtually the same, albeit with some changes and omissions for purposes of cinematic style, time, and budget constraints. Michael Goldenberg also received input from Rowling during his adaptation of the fifth novel; Goldenberg was originally considered to adapt the first novel before the studio chose Kloves.[43]

In a 2010 interview, Heyman briefly explained the book-to-film transition. He commented on Rowling's involvement in the series, stating that she understood that "books and films are different" and was "the best support" a producer could have. Rowling had overall approval on the scripts, which were viewed and discussed by the director and the producers. Heyman also said that Kloves was the "key voice" in the process of adapting the novels and that certain aspects from the books needed to have been excluded from the scripts due to the filmmakers' decision to keep the main focus on Harry's journey as a character, which would ultimately give the films a defined structure. Heyman mentioned that some fans "don't necessarily understand the adaptation process" and that the filmmakers would have loved to "have everything" from the books in the films but noted that it was not possible since they had "neither time nor cinematic structure" to do so. He finished by saying that adapting a novel to the screen is "a really considered process".[44]

Because the films were being made as the novels were being published, the filmmakers had no idea of the story's outcome until the release of the final novel in 2007. Kloves spoke of his relationship with Rowling when adapting the novels by saying, "The thing is about Jo, which is remarkable for someone who had no experience with the filmmaking process, was her intuition. We had a conversation the very first day I met her where she said, 'I know the movies can't be the books ... because I know what's coming and it's impossible to fully dramatise on screen what I'm going to write. But I just ask you to be true to the characters; that's all I care about.'"[45] Kloves also said, "I don't know what compelled me to say this [to Rowling], but I said, 'I've just got to warn you my favourite character is not Harry. My favourite character is Hermione.' And I think for some weird reason, from that moment on, she sort of trusted me."[45]

Cast and crew

Aside from the three lead actors, other notable cast members include Robbie Coltrane as Rubeus Hagrid, Tom Felton as Draco Malfoy, Alan Rickman as Severus Snape, and Dame Maggie Smith as Minerva McGonagall. Richard Harris, who played the role of Professor Albus Dumbledore, died on 25 October 2002, causing the role to be re-cast to Michael Gambon for Prisoner of Azkaban. Heyman and Cuarón chose Gambon to portray Dumbledore, which he did for all succeeding films. Notable recurring cast members include Helena Bonham Carter as Bellatrix Lestrange, Warwick Davis as Filius Flitwick, Ralph Fiennes as Lord Voldemort, Brendan Gleeson as Alastor Moody, Richard Griffiths as Vernon Dursley, Jason Isaacs as Lucius Malfoy, Gary Oldman as Sirius Black, Fiona Shaw as Petunia Dursley, Timothy Spall as Peter Pettigrew, David Thewlis as Remus Lupin, Emma Thompson as Sybill Trelawney, Mark Williams as Arthur Weasley, and Julie Walters as Molly Weasley.

The series has seen many returning crew members from various departments, including Tim Burke, visual effects supervisor; Peter Doyle, digital film colourist; Nick Dudman, make-up and creature effects designer; David Holmes, stunt double; Amanda Knight, make-up artist; Stephenie McMillan, set designer; Greg Powell, stunt coordinator; Jany Temime, costume designer; and Fiona Weir, casting director.

Set design

The production designer for all eight films is Stuart Craig. Assisted by Stephenie McMillan, Craig has created iconic sets pieces including the Ministry of Magic, the Chamber of Secrets, Malfoy Manor, and the layout for the CGI Horcrux Cave. Because the novels were being published as the films were being made, Craig was required to rebuild some sets for future films and alter the design of Hogwarts.[48]

He said, "In the early days, every time you saw the exterior of Hogwarts, it was a physical miniature", which was made by craftsmen and occupied a large sound stage.[49][50] "We ended up with a profile of how Hogwarts looked, a skyline that actually I didn't design, and it wasn't always satisfactory, and as all the novels got written and movies got made there were new requirements [for buildings]. The [Astronomy Tower] definitely wasn't there originally, and so we were able to add that substantial piece. And in the last film, we needed an arena for the battle for Hogwarts – the big courtyard outside doubled in size, and if you look at the first movie it wasn't there at all. There were quite some liberties taken with the continuity of Hogwarts."[51] In the last film, Craig used a digital model instead of a miniature to "embrace the latest technology".[50]

On the method of creating the sets, Craig said he often started by sketching ideas onto a blank sheet of paper.[52] Stephenie McMillan also said that "each film always had plenty of new challenges", citing the changes in visual style between directors and cinematographers as an example, along with the developing story in the novels. Due to J.K. Rowling's descriptions of various settings in the novels, Craig noted his "responsibility was to place it together".[53]

Craig commented on his experience working in the studio environment: "I'm the production designer, but on a big movie like Harry Potter I may be responsible for 30 to 35 people; from the supervising art director, and a team of art directors and assistants, to draughtsmen and junior draughtsmen, and then on to model makers, sculptors and scenic artists." He said, "Ten years ago, all the Harry Potter drawings were done in pencil. I would take my roughs and plans and sections and give them to a professional architectural illustrator, who would create concept art using pencil and colour wash on watercolour paper." He said the process changed slightly throughout the years due to, what he called, the "digital revolution" of making films.[50]

When filming of the series was completed, some of Craig's sets had to be rebuilt or transported for them to be displayed at the Warner Bros. studio tour.[49]

Cinematography

Six directors of photography worked on the series: John Seale on the first film, Roger Pratt on the second and fourth, Michael Seresin on the third, Sławomir Idziak on the fifth, Bruno Delbonnel on the sixth, and Eduardo Serra on the seventh and eighth. Delbonnel was considered to return for both parts of Deathly Hallows, but he declined, stating that he was "scared of repeating" himself.[55] Delbonnel's cinematography in Half-Blood Prince gained the series its only Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography. As the series progressed, each cinematographer faced the challenge of shooting and lighting older sets (which had been around since the first few films) in unique and different ways.[56] Chris Columbus said the series' vivid colouring decreased as each film was made.[32][57]

Michael Seresin commented on the change of visual style from the first two films to Prisoner of Azkaban: "The lighting is moodier, with more shadowing and cross-lighting." Seresin and Alfonso Cuarón moved away from the strongly coloured and brightly lit cinematography of the first two films, with dimmer lighting and a more muted colour palette being utilised for the succeeding five films.[58] After comparing a range of digital cameras with 35 mm film, Bruno Delbonnel decided to shoot the sixth movie, Half-Blood Prince, on film rather than the increasingly popular digital format. This decision was kept for the two-part Deathly Hallows with Eduardo Serra, who said that he preferred to work with film because it was "more technically accurate and dependable".[59]

Because the majority of Deathly Hallows takes place in various settings away from Hogwarts, David Yates wanted to "shake things up" by using different photographic techniques such as using hand-held cameras and very wide camera lenses.[60] Eduardo Serra said, "Sometimes we are combining elements shot by the main unit, a second unit, and the visual effects unit. You have to know what is being captured – colours, contrast, et cetera – with mathematical precision." He noted that with Stuart Craig's "amazing sets and the story", the filmmakers could not "stray too far from the look of the previous Harry Potter films".[59][61]

Editing

Along with continuous changes in cinematographers, there have been five film editors to work in post-production on the series: Richard Francis-Bruce edited the first instalment, Peter Honess the second, Steven Weisberg the third, Mick Audsley the fourth, and Mark Day films five through eight.

Music

The Harry Potter series has had four composers. John Williams scored the first three films: Philosopher's Stone, Chamber of Secrets, and Prisoner of Azkaban. Due to a busy 2002 schedule, Williams brought in William Ross to adapt and conduct the score for Chamber of Secrets. Williams also composed "Hedwig's Theme", the series' leitmotif which appears in all eight films.[62]

After Williams left the series to pursue other projects, Patrick Doyle scored the fourth entry, Goblet of Fire, which was directed by Mike Newell, with whom Doyle had worked previously. In 2006, Nicholas Hooper started work on the score to Order of the Phoenix, reuniting with director David Yates. Hooper also composed the soundtrack to Half-Blood Prince but decided not to return for the final two films.

In January 2010, Alexandre Desplat was confirmed to compose the score for Deathly Hallows – Part 1.[63] The film's orchestration started in the summer with Conrad Pope, the orchestrator on the first three Harry Potter films, collaborating with Desplat. Pope commented that the music "reminds one of the old days".[64] Desplat returned to score Deathly Hallows – Part 2 in 2011.[65]

Yates stated that he wanted Williams to return to the series for the final instalment, but their schedules did not align due to the urgent demand for a rough cut of the film.[66] The final recording sessions for Harry Potter took place on 27 May 2011 at Abbey Road Studios with the London Symphony Orchestra, Desplat and orchestrator Conrad Pope.[67]

Doyle, Hooper and Desplat introduced their own personal themes to their respective soundtracks, while keeping a few of Williams' themes.

Visual effects

There have been many visual effects companies that work on the Harry Potter series. Some of these include Rising Sun Pictures, Sony Pictures Imageworks, Double Negative, Cinesite, Framestore, and Industrial Light & Magic. The latter three have worked on all the films in the series, while Double Negative and Rising Sun Pictures began their commitments with Prisoner of Azkaban and Goblet of Fire, respectively. Framestore contributed by developing many memorable creatures and sequences to the series.[68] Cinesite was involved in producing both miniature and digital effects for the films.[69] Producer David Barron said that "Harry Potter created the UK effects industry as we know it. On the first film, all the complicated visual effects were done on the [US] west coast. But on the second, we took a leap of faith and gave much of what would normally be given to Californian vendors to UK ones. They came up trumps." Tim Burke, the visual effects supervisor, said many studios "are bringing their work to UK effects companies. Every facility is fully booked, and that wasn't the case before Harry Potter. That's really significant."[31]

Final filming

On 12 June 2010, filming of the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 and Part 2 was completed with actor Warwick Davis stating on his Twitter account, "The end of an Era – today is officially the last day of principal photography on 'Harry Potter' – ever. I feel honoured to be here as the director shouts cut for the very last time. Farewell Harry & Hogwarts, it's been magic!"[70] However, reshoots of the epilogue scene were confirmed to begin in the winter of 2010. The reshoots were completed on 21 December 2010, marking the official closure of filming for the Harry Potter franchise.[71] Exactly four years earlier on that day, Rowling's official website revealed the title of the final novel in the book series – Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.[72]

Films

Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001)

Harry Potter is an orphaned boy brought up by his unkind Muggle (non-magical) aunt and uncle. At the age of eleven, half-giant Rubeus Hagrid informs him that he is actually a wizard and that his parents were murdered by an evil wizard named Lord Voldemort. Voldemort also attempted to kill one-year-old Harry on the same night, but his killing curse mysteriously rebounded and reduced him to a weak and helpless form. Harry became extremely famous in the Wizarding World as a result. Harry begins his first year at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry and learns about magic. During the year, Harry and his friends Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger become entangled in the mystery of the Philosopher's Stone which is being kept within the school.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)

Harry, Ron, and Hermione return to Hogwarts for their second year, which proves to be more challenging than the last. The Chamber of Secrets has been opened, leaving students and ghosts petrified by an unleashed monster. Harry must face up to claims that he is the heir of Salazar Slytherin (founder of the Chamber), learn that he can speak Parseltongue, and also discover the properties of a mysterious diary, only to find himself trapped within the Chamber itself.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)

Harry's third year sees the boy wizard, along with his friends, attending Hogwarts School once again. Professor R. J. Lupin joins the staff as Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher, while convicted murderer Sirius Black escapes from Azkaban. The Ministry of Magic entrusts the Dementors to guard Hogwarts from Black. Harry learns more about his past and his connection with the escaped prisoner.

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005)

During Harry's fourth year, Hogwarts plays host to the Triwizard Tournament. Three European schools participate in the tournament, with three 'champions' representing each school in the deadly tasks. The Goblet of Fire chooses Fleur Delacour, Viktor Krum, and Cedric Diggory to compete against each other. However, Harry's name is also produced from the Goblet thus making him a fourth champion, which leads to a terrifying encounter with a reborn Lord Voldemort.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)

Harry's fifth year begins with him being attacked by Dementors in Little Whinging. Later, he finds out that the Ministry of Magic is in denial of Lord Voldemort's return. Harry is also beset by disturbing and realistic nightmares, while Professor Umbridge, a representative of Minister for Magic Cornelius Fudge, is the new Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher. Harry becomes aware that Voldemort is after a prophecy which reveals: "neither can live while the other survives". The rebellion involving the students of Hogwarts, secret organisation Order of the Phoenix, the Ministry of Magic, and the Death Eaters begins.

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)

In Harry's sixth year at Hogwarts, Lord Voldemort and his Death Eaters are increasing their terror upon the Wizarding and Muggle worlds. Headmaster Albus Dumbledore persuades his old friend Horace Slughorn to return to Hogwarts as a professor as there is a vacancy to fill. There is a more important reason, however, for Slughorn's return. While in a Potions lesson, Harry takes possession of a strangely annotated school textbook, inscribed as belonging to the 'Half-Blood Prince'. Draco Malfoy struggles to carry out a mission presented to him by Voldemort. Meanwhile, Dumbledore and Harry secretly work together to discover how to destroy the Dark Lord once and for all.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 (2010)

After unexpected events at the end of the previous year, Harry, Ron, and Hermione are entrusted with a quest to find and destroy Lord Voldemort's secret to immortality – the Horcruxes. It is supposed to be their final year at Hogwarts, but the collapse of the Ministry of Magic and Voldemort's rise to power prevents them from attending. The trio undergo an arduous journey with many obstacles in their path including Death Eaters, Snatchers, the mysterious Deathly Hallows, and Harry's connection with the Dark Lord's mind becoming stronger.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011)

After destroying a Horcrux and discovering the significance of the three Deathly Hallows, Harry, Ron and Hermione continue to seek out the other Horcruxes in an attempt to destroy Voldemort, who has now obtained the powerful Elder Wand. The Dark Lord discovers Harry's hunt for his Horcruxes and launches an attack on Hogwarts, where the trio return for one last stand against the dark forces that threaten both the Wizarding and Muggle worlds.

Release

The rights to the first four novels in the series were sold to Warner Bros. for £1,000,000 by J.K. Rowling. After the release of the fourth book in July 2000, the first film, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was released on 16 November 2001. In its opening weekend, the film grossed $90 million in the United States alone, which set a record opening worldwide. The succeeding three motion picture adaptations followed suit in financial success, while garnering positive reviews from fans and critics. The fifth film, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, was released by Warner Bros. on 11 July 2007 in English-speaking countries, except for the UK and Ireland, which released the movie on 12 July.[73] The sixth, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, was released on 15 July 2009 to critical acclaim and finished its theatrical run ranked as the number two grossing film of 2009 on the worldwide charts.

The final novel, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, was split into two cinematic parts: Part 1 was released on 19 November 2010, and Part 2, the conclusion of the series, was released on 15 July 2011.[74] Part 1 was originally scheduled to be released in 3D and 2D,[75] but due to a delay in the 3D conversion process, Warner Bros. released the film only in 2D and IMAX cinemas. However, Part 2 was released in 2D and 3D cinemas as originally planned.[76]

The television broadcast rights for the series in the US are currently held by NBCUniversal, which typically airs the films on USA Network and Syfy.[77] The film series has accrued nearly 1.3 billion viewings since its television debut—the highest-watched franchise in television broadcast history.[78] All eight films became available to stream on HBO Max on 27 May 2020, the launch date of the service.[79]

In celebration of the 20th anniversary of the release of Philosopher's Stone, in November 2021, it was announced that the entire film series would be relaunched in cinemas in Brazil, as well as a special edition of Philosopher's Stone on HBO Max.[80] Much of the original cast and crew reunited for an HBO Max retrospective special titled Harry Potter 20th Anniversary: Return to Hogwarts, which was released on 1 January 2022.[81]

Reception

The Harry Potter films have been top-rank box office hits, with all eight releases on the list of highest-grossing films worldwide. Philosopher's Stone was the highest-grossing Harry Potter film up until the release of the final instalment of the series, Deathly Hallows Part 2, while Prisoner of Azkaban grossed the least.[82] As well as being a financial success, the film series has also been a success among film critics.[83][84] Opinions of the films are generally divided among fans, with one group preferring the more faithful approach of the first two films, and another group preferring the more stylised character-driven approach of the later films.[85] Rowling has been consistently supportive of all the films and evaluated Deathly Hallows as her "favourite one" in the series.[86][87][88]

Critical response

All the films have been a success financially and critically, making the franchise one of the major Hollywood "tent-poles" akin to James Bond, Star Wars, Indiana Jones and Pirates of the Caribbean. The series is noted by audiences for growing visually darker and more mature as each film was released.[32][89] However, the films have generally divided fans of the books, with some preferring the more faithful approach of the first two films and others preferring the more stylised character-driven approach of the later films.

Some have also felt the series has a "disjointed" feel due to the changes in directors, as well as Michael Gambon's portrayal of Albus Dumbledore differing from that of Richard Harris. Author J. K. Rowling has been consistently supportive of the films,[90][91][92] and evaluated the two parts of Deathly Hallows as her favourite of the series. She wrote on her website of the changes in the book-to-film transition, "It is simply impossible to incorporate every one of my storylines into a film that has to be kept under four hours long. Obviously films have restrictions – novels do not have constraints of time and budget; I can create dazzling effects relying on nothing but the interaction of my own and my readers' imaginations."[93]

| Film | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic | CinemaScore[94] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philosopher's Stone | 81% (7.06/10 average rating) (200 reviews)[95] | 65 (37 reviews)[96] | A |

| Chamber of Secrets | 82% (7.21/10 average rating) (237 reviews)[97] | 63 (35 reviews)[98] | A+ |

| Prisoner of Azkaban | 90% (7.85/10 average rating) (258 reviews)[99] | 82 (40 reviews)[100] | A |

| Goblet of Fire | 88% (7.45/10 average rating) (255 reviews)[101] | 81 (38 reviews)[102] | |

| Order of the Phoenix | 78% (6.9/10 average rating) (256 reviews)[103] | 71 (37 reviews)[104] | A− |

| Half-Blood Prince | 84% (7.12/10 average rating) (279 reviews)[105] | 78 (36 reviews)[106] | |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | 77% (7.09/10 average rating) (288 reviews)[107] | 65 (42 reviews)[108] | A |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | 96% (8.34/10 average rating) (332 reviews)[109] | 85 (41 reviews)[110] |

Accolades

At the 64th British Academy Film Awards in February 2011, J. K. Rowling, David Heyman, David Barron, David Yates, Alfonso Cuarón, Mike Newell, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson collected the Michael Balcon Award for Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema for the series.[111][112]

In addition, the American Film Institute recognised the entire series with a Special Award at the American Film Institute Awards in 2011. Special awards "are given to outstanding achievements in the moving image that do not fit into AFI's criteria for the other honorees".[113] In its press release, the Institute referred to the films as "a landmark series; eight films that earned the trust of a generation who wished for the beloved books of J.K. Rowling to come to life on the silver screen. The collective wizardry of an epic ensemble gave us the gift of growing older with Harry, Ron and Hermione as the magic of Hogwarts sprung from the films and into the hearts and minds of Muggles around the world."[113]

Harry Potter was also recognised by the BAFTA Los Angeles Britannia Awards, with David Yates winning the Britannia Award for Artistic Excellence in Directing for his four Harry Potter films.[114][115]

Academy Awards

| Motion Picture | Nominated category | Nominee(s) | Ceremony |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone | Best Art Direction | Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan | 74th Academy Awards |

| Best Costume Design | Judianna Makovsky | ||

| Best Original Score | John Williams | ||

| Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban | Best Original Score | John Williams | 77th Academy Awards |

| Best Visual Effects | Roger Guyett, Tim Burke, John Richardson and Bill George | ||

| Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire | Best Art Direction | Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan | 78th Academy Awards |

| Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince | Best Cinematography | Bruno Delbonnel | 82nd Academy Awards |

| Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | Best Art Direction | Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan | 83rd Academy Awards |

| Best Visual Effects | Tim Burke, John Richardson, Christian Manz and Nicolas Aithadi | ||

| Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | Best Art Direction | Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan | 84th Academy Awards |

| Best Makeup | Nick Dudman, Amanda Knight and Lisa Tomblin | ||

| Best Visual Effects | Tim Burke, David Vickery, Greg Butler and John Richardson |

Six of the eight films were nominated for a total of 12 Academy Awards.

Some critics, fans, and general audiences have expressed disappointment over the Harry Potter series not winning any Oscars for its achievements. However, others have pointed out that certain films in the series had uneven reviews, in contrast to the three films of The Lord of the Rings, for example, which were all critically acclaimed. This has been partly attributed to the Harry Potter series going through several directors each with their own directorial style in contrast to the Lord of the Rings trilogy, which was filmed in one massive undertaking by the same director, writer, and producer.[116][117] An observer noted that "cinematically, the Potter franchise-starter was marked by its commercial caution: its imagination was safely limited, its storytelling by-the-book in all senses, its budget spent to yield more value than magic" in contrast with how "Fellowship of the Ring, by comparison, was a reckless, wondrous extravagance".[118]

Although not successful at the Oscars, the Harry Potter series has gained success in many other award ceremonies, including the annual Saturn Awards and Art Directors Guild Awards. The series has also gained a total of 24 nominations at the British Academy Film Awards presented at the annual BAFTAs, winning several, and 5 nominations at the Grammy Awards.

Philosopher's Stone achieved seven BAFTA Award nominations, including Best British Film and Best Supporting Actor for Robbie Coltrane.[119] The film was also nominated for eight Saturn Awards and won for its costumes design.[120] It was also nominated at the Art Directors Guild Awards for its production design[121] and received the Broadcast Film Critics Award for Best Live Action Family Film along with gaining two other nominations.[122]

Chamber of Secrets won the award for Best Live Action Family Film in the Phoenix Film Critics Society. It was nominated for seven Saturn Awards, including Best Director and Best Fantasy Film. The film was nominated for four BAFTA Awards and a Grammy Award for John Williams's score. Prisoner of Azkaban won an Audience Award, as well as Best Feature Film, at the BAFTA Awards. The film also won a BMI Film Music award along with being nominated at the Grammy Awards, Visual Effect Society Awards, and the Amanda Awards. Goblet of Fire won a BAFTA award for Best Production Design as well as being nominated at the Saturn Awards, Critic's Choice Awards, and the Visual Effects Society Awards.

Order of the Phoenix picked up three awards at the inaugural ITV National Movie Awards.[123] At the Empire Awards, David Yates won Best Director.[124] Composer Nicholas Hooper received a nomination for a World Soundtrack Discovery Award.[125] The film was nominated at the BAFTA Awards, but did not win for Best Production Design or Best Special Visual Effects.[126] Half-Blood Prince was nominated for BAFTA Awards in Production Design and Visual Effects,[127] and it was in the longlists for several other categories, including Best Supporting Actor for Alan Rickman.[128] Amongst other nominations and wins, the film also achieved Best Family Movie at the National Movie Awards as well as Best Live Action Family Film at the Phoenix Film Critics Society Awards, along with being nominated for Best Motion Picture at the Satellite Awards.

Deathly Hallows – Part 1 gained two nominations at the BAFTA Awards for Best Make-Up and Hair and Best Visual Effects, along with receiving nominations for the same categories at the Broadcast Film Critics Association Awards. Eduardo Serra's cinematography and Stuart Craig's production design were also nominated in various award ceremonies, and David Yates attained his second win at the Empire Awards, this time for Best Fantasy Film. He also obtained another Best Director nomination at the annual Saturn Awards, which also saw the film gain a Best Fantasy Film nomination.[129][130] Deathly Hallows – Part 2 was released to critical acclaim, gaining a mix of audience awards. Part 2 of Deathly Hallows was also recognised at the Saturn Awards as well as the BAFTA Awards, where the film achieved a win for Best Special Visual Effects.[131]

Box office performance

As of 2022[update], the Harry Potter film series is the fourth highest-grossing film franchise of all time, with the eight films released grossing over $7.7 billion worldwide. Without adjusting for inflation, this is higher than the first 22 James Bond films and the six films in the Star Wars original and prequel trilogies.[132] Chris Columbus's Philosopher's Stone became the highest-grossing Harry Potter film worldwide upon completing its theatrical run in 2002, but it was eventually topped by David Yates's Deathly Hallows – Part 2, while Alfonso Cuarón's Prisoner of Azkaban grossed the least.[133][134][135][136]

Six films in the Harry Potter franchise — Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince and Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Parts 1 & 2 — have to date grossed around $216 million in IMAX theaters worldwide.[137]

| Motion picture | Release date | Box office gross | Budget | Ref(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | USA & Canada (approx. ticket sales) |

Other countries | Worldwide | ||||

| Philosopher's Stone | 16 November 2001 | £66,096,060 | $318,886,962 (55,976,200) |

$703,403,056 | $1,022,290,019 | $125 million | [138][139][140][141][142] |

| Chamber of Secrets | 14 November 2002 | £54,780,731 | $262,450,136 (44,978,900) |

$617,152,229 | $879,602,366 | $100 million | [140][141][143][144] |

| Prisoner of Azkaban | 31 May 2004 | £45,615,949 | $249,975,996 (40,183,700) |

$547,385,621 | $797,361,618 | $130 million | [140][141][145] |

| Goblet of Fire | 18 November 2005 | £48,328,854 | $290,417,905 (45,188,100) |

$606,260,335 | $896,678,241 | $150 million | [140][141][146][147] |

| Order of the Phoenix | 11 July 2007 | £49,136,969 | $292,353,413 (42,442,500) |

$649,818,982 | $942,172,396 | $150 million | [140][141][148][149][150] |

| Half-Blood Prince | 15 July 2009 | £50,713,404 | $302,305,431 (40,261,200) |

$632,148,664 | $934,454,096 | $250 million | [140][141][151][152] |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | 19 November 2010 | £52,364,075 | $296,347,721 (37,503,700) |

$680,695,761 | $977,043,483 | Less than $250 million (official) | [153] |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | 15 July 2011 | £73,094,187 | $381,409,310 (48,046,800) |

$960,912,354 | $1,342,321,665 | [141][156][157] | |

| Total | £440,269,736 | $2,393,347,532 | $5,383,254,496 | $7,776,602,036 | $1.155 billion | [158] | |

All-time rankings

| Motion picture | Rank | Ref(s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-time (worldwide) |

All-time (United States) |

All-time (United Kingdom) |

Yearly (United States) |

Yearly (worldwide) |

Opening day (all-time) |

Opening weekend (all-time) | ||

| Philosopher's Stone | #47 | #76 | #9 | #1 | #1 | #66 | #55 | [138] |

| Chamber of Secrets | #68 | #114 | #17 | #4 | #2 | #81 | #60 | [140][143][144] |

| Prisoner of Azkaban | #90 | #131 | #33 | #6 | #47 | #49 | [140] | |

| Goblet of Fire | #63 | #101 | #28 | #3 | #1 | #41 | #40 | [140][146][147] |

| Order of the Phoenix | #57 | #96 | #25 | #5 | #2 | #34 | #77 | [140][148][149] |

| Half-Blood Prince | #59 | #88 | #24 | #3 | #24 | #75 | [140][151][152] | |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 1 | #48 | #91 | #18 | #5 | #3 | #22 | #25 | [140][154][155] |

| Deathly Hallows – Part 2 | #13 | #42 | #7 | #1 | #1 | #3 | #12 | [157][159] |

Legacy

Harry Potter was in the vanguard of a new approach to big-budget film-making. Most modern blockbuster franchises have two things in common: they are based on known properties such as books and comics, and they are steered by respected but little-known directors.

The Harry Potter films and their success have been retrospectively considered to have had a significant impact on the film industry. They are credited with helping redefine the Hollywood blockbuster in the 21st century by initiating a shift toward established media franchises forming the basis of successful films. In the wake of the final film's release, Claudia Puig of USA Today wrote that the films "inspired every major studio to try to capture [its] alchemic formula, spawning a range of copycats and wannabes" and "also have shown Hollywood how to make a glossy blockbuster with an eye toward keeping costs down".[161] A 2009 article from The Economist argued that the films were "in the vanguard" of adaptations of established properties being the modern film franchise model, citing The Lord of the Rings, Spider-Man and The Dark Knight Trilogy as examples of successful film series that followed Harry Potter's suit.[160] Furthermore, the practice of splitting the finale of a film series into two back-to-back films began with the success of Deathly Hallows, and it would soon be replicated by The Twilight Saga: Breaking Dawn – Parts 1 and 2, and The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Parts 1 and 2.[162]

The films are also credited with signalling the popularity of films based on children's and young adult literature in the 2000s and 2010s, correlating with the book series' own literary influence. Costance Grady and Aja Romano, commenting on the whole Harry Potter franchise's legacy for Vox in light of its 20th anniversary, wrote that youth-targeted literature has since become "a go-to well of ideas for Hollywood", pointing to the successes of The Twilight Saga and The Hunger Games.[163]

The series has spawned a vast volume of fan fiction, with nearly 600,000 inspired stories catalogued,[164] and an Italian fan film, Voldemort: Origins of the Heir, which received over twelve million views in ten days on YouTube.[165]

See also

Notes

- ^ This screen test footage was released via the first set of Ultimate Editions in 2009.[25]

- ^ Not including executive producers

References

- ^ Kois, Dan (13 July 2011). "The Real Wizard Behind Harry Potter". Slate. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ^ "Fantasy – Live Action". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2 September 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ "Fantastic Beasts release shows the magic in brand reinvention". Campaignlive.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b Dargis, Manohla; Scott, A. O. (15 July 2007). "Harry Potter and the Four Directors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter at Leavesden". WB Studio Tour. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Plans Two-Part Film Adaptation of "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows" to Be Directed by David Yates". Business Wire. 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

expand the screen adaptation of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows and release the film in two parts.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff; Eller, Claudia (7 November 2010). "The end nears for 'Harry Potter' on film". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

The fantasy epic begins its Hollywood fade-out Nov. 19 with the release of 'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1' and finishes next summer with the eighth film, 'Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2.'

- ^ Schuker, Lauren A. E. (22 November 2010). "'Potter' Charms Aging Audience". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

The seventh instalment in the eight-film franchise, "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I" took in a franchise record of $125.1 million at domestic theaters this weekend according to Warner Bros., the Time Warner Inc.-owned movie studio behind the films.

- ^ a b c d e "Hero Complex". Los Angeles Times. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 24 July 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ "WiGBPd About Harry". Australian Financial Review. 19 July 2000. Archived from the original on 4 January 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone". The Guardian. UK. 16 November 2001. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ Fordy, Tom (3 January 2022). "JK Rowling's battle to make the Harry Potter films '100 per cent British'". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ Linder, Brian (23 February 2000). "No "Harry Potter" for Spielberg". IGN. Archived from the original on 23 November 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ "For Spielberg, making a Harry Potter movie would have been no challenge". Hollywood.com. 5 September 2001. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2007.

- ^ Rowling, J.K. "Rubbish Bin: J. K. Rowling "veto-ed" Steven Spielberg". JKRowling.com. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ Schmitz, Greg Dean. "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001)". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 30 May 2007.

- ^ Linder, Brian (7 March 2000). "Two Potential "Harry Potter" Director's Back Out". IGN. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Davidson, Paul (15 March 2000). "Harry Potter Director Narrowed Down". IGN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ "Terry Gilliam bitter about Potter". Wizard News. 29 August 2005. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ a b c Linder, Bran (28 March 2000). "Chris Columbus to Direct Harry Potter". IGN. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (24 February 2000). "A Wizard of Hollywood". Salon. Archived from the original on 10 July 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Linder, Brian (30 March 2000). "Chris Columbus Talks Potter". IGN. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ Brian Linder (17 May 2000). "Bewitched Warner Bros. Delays Potter". IGN. Archived from the original on 9 February 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ^ "Ultimate Edition: Screen Test, Trio Casting and Finding Harry Potter". Mugglenet.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Young Daniel gets Potter part". BBC Online. 21 August 2000. Archived from the original on 18 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson bring Harry, Ron and Hermione to life for Warner Bros. Pictures' "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone"". Warner Brothers. 21 August 2000. Archived from the original on 14 April 2002. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Studio Tour London – The Making of Harry Potter". www.wbstudiotour.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "Warner Bros. Pictures mentions J. K. Rowling as producer". Business Wire. 20 September 2010. Archived from the original on 27 December 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Richards, Olly (14 March 2008). "Potter Producer Talks Deathly Hallows". Empire. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Gilbey, Ryan (7 July 2011). "Ten years of making Harry Potter films, by cast and crew". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "Christopher Columbus Remembers Harry Potter". Empire Online. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

We realised that these movies would get progressively darker. Again, we didn't know how dark but we realised that as the kids get older, the movies get a little edgier and darker.

- ^ "Harry Potter, Dissected". The New York Times. 14 July 2007. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Chris Columbus". BBC Online. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Columbus "Burned Out"". Blogs.coventrytelegraph.net. 6 July 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Alfonso Cuaron: the man behind the magic". Newsround. 24 May 2004. Archived from the original on 7 November 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Alfonso Cuarón Talks Harry Potter". Empire. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ a b c "Mike Newell on Harry Potter". Empire Online. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ a b c "Deathly Hallows Director David Yates On Harry Potter". Empire Online. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "Heyman on directors". Orange.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Amy Raphael (24 June 2007). "How I raised Potter's bar". The Observer. London. Archived from the original on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ^ "Harry Potter & The Order Of The Phoenix – Daniel Radcliffe interview". Indie London. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2012.

- ^ "Introducing Michael Goldenberg: The OotP scribe on the Harry Potter films, franchise, and fandom OotP Film". The Leaky Cauldron. 10 April 2007. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "Heyman talks adaptation". Firstshowing.net. 9 December 2010. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ a b "Steve Kloves Talks Harry Potter". Empire Online. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ^ "Harry Potter fans boost Oxford Christ Church Cathedral" Archived 15 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Visitor Information: Harry Potter". Christ Church, Oxford. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "OSCARS: Production Designer Stuart Craig — 'Harry Potter'". The Deadline Team. 20 February 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ a b "From Sketch to Still: From Marbling Gringotts to Painting Diagon Alley, How Harry Potter's Art Direction Earned Its Oscar Nod". Vanity Fair. 14 February 2012. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ a b c "Drawn to cinema: An interview with Stuart Craig". Beat Magazine. 30 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena (7 February 2012). "Harry Potter and the Continuity Question". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "Stuart Craig Interview Transcript". ArtInsights. Archived 13 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Tech Support Interview: Stuart Craig and Stephenie McMillan on a decade of designing 'Harry Potter'". HitFix. 10 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "HARRY POTTER Studio Tour Opens in 2012". Collider.com. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Rosi (1 March 2010). "Delbonnel on Potter". The-leaky-cauldron.org. Archived from the original on 4 March 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Bruno Delbonnel talks shooting Half-Blood Prince to mark Oscar nomination". Mugglenet. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "Bringing a Wizard's Dark World to Life". The Wall Street Journal. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 15 January 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "A Wizard Comes Of Age". Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Kodak Celebrates the Oscars® Feature: Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1". Kodak. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ "Deathly Hallows to Be Shot Using 'Loads of Hand-Held Cameras,' Tom Felton Talks Sectumsempra in Half-Blood Prince". The Leaky Cauldron. 31 March 2009. Archived from the original on 4 April 2009. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ "Lensers aren't afraid of the dark". Variety. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

What I loved about the last film is that David pushed me to go dark, which all cinematographers love to do. And usually you're fighting with the producers (about the look) but they all wanted it dark and atmospheric, too.

- ^ "Harry Potter soundtrack: 'Hedwig's Theme' and everything to know about the film franchise's magical score". Classic FM. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ^ MuggleNet (19 January 2010). "CONFIRMED – Desplat for DH". Mugglenet.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Pope on Desplat's HP7 Pt.1 Score". Snitchseeker.com. 28 August 2010. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Alexandre Desplat – Composer of Part 1 and 2 (NOTE: Click "About the Movie", then "Filmmakers", then "Alexandre Desplat")". Harrypotter.warnerbros.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ MuggleNet (12 November 2010). "Yates on Williams, Part 2". Mugglenet.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Conrad Pope". www.facebook.com. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ^ "Framestore – We are Framestore. Extraordinary images, extraordinary talent". Framestore. Archived from the original on 30 January 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ "Cinesite, HP 1–7". Cinesite.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "June 2010 Filming completed". Snitchseeker.com. 12 June 2010. Archived from the original on 17 August 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "10 Years Filming – 24Dec2010". Snitchseeker.com. 21 December 2010. Archived from the original on 27 February 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ MuggleNet (21 December 2010). "JK Title reveal". Mugglenet.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)". IMDb.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ "WB Name Drops Big Titles". ERCBoxOffice. 23 February 2009. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2009.

- ^ "DH Part 1 and 2 in 3D and 2D". Snitchseeker.com. 19 November 2010. Archived from the original on 7 August 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Part 1 Not in 3D". Cinemablend.com. 8 October 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Gottfried, Miriam (8 August 2016). "Why Harry Potter Is NBCUniversal's Chosen One". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Flint, Joe (8 August 2016). "NBCUniversal Places Big Bet on 'Harry Potter,' 'Fantastic Beasts'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ Nick Romano (27 May 2020). "All eight Harry Potter films magically arrive on HBO Max for platform launch". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ^ "20 Anos Desde O Primeiro Filme, Saga Harry Potter Voltará Aos Cinemas". Portal Exibidor. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ^ "Harry Potter cast return to Hogwarts to mark 20th anniversary of first film". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ^ "Box Office Harry Potter". The-numbers.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo". boxofficemojo.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter: Books vs films". Digital Spy. 9 July 2007. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ^ "Potter Power!". Time For Kids. Archived from the original on 1 December 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (27 May 2004). "New 'Potter' movie sneaks in spoilers for upcoming books". USA Today. Archived from the original on 4 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "JK 'loves' Goblet of Fire movie". Newsround. BBC. 7 November 2005. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter Films Get Darker and Darker". The Wall Street Journal. 18 November 2010. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

* "Harry Potter: Darker, Richer and All Grown Up". Time. 15 July 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

* "Review: "Harry Potter" goes out with magical, and dark, bang". Reuters. 6 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

* "Isn't It About Time You Gave The Chris Columbus Harry Potter Films Another Chance?". SFX UK. 3 December 2011. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2012. - ^ "Potter Power!". Time For Kids. Archived from the original on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ Puig, Claudia (27 May 2004). "New Potter movie sneaks in spoilers for upcoming books". USA Today. Archived from the original on 1 July 2004. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ "JK "loves" Goblet Of Fire movie". CBBC. 7 November 2005. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007. Retrieved 31 May 2007.

- ^ Rowling, J. K. "How did you feel about the POA filmmakers leaving the Marauder's Map's background out of the story? (A Mugglenet/Lexicon question)". J. K. Rowling Official Site. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

- ^ "CinemaScore". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 23 November 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 11 July 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 23 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 (2010)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part I (2010)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2 (2011)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Harry Potter franchise to get Outstanding BAFTA award". BBC Online. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema in 2011 – The Harry Potter films". BAFTA. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ a b "American Film Institute". afi.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2013. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ^ "BAFTA Honors John Lasseter and David Yates 11/30". Broadway World (Los Angeles). 28 June 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

The worldwide success of Mr. Lasseter for Walt Disney and Pixar Animation Studios and Mr. Yates' contribution to the final four parts of the 'Harry Potter' franchise makes them global wizards in their own right, and are delighted to honor these remarkable filmmakers with this year's Britannia Award.

- ^ "John Lasseter and David Yates set to be honored by BAFTA Los Angeles". Los Angeles Times. 28 June 2011. Archived from the original on 3 July 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ McNamara, Mary (2 December 2010). "Critic's Notebook: Can 'Harry Potter' Ever Capture Oscar Magic?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- ^ "Potter Oscar Magic". Thespec.com. 26 November 2010. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ "Fellowship of the Ring at 20: the film that revitalised and ruined Hollywood". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Film Nominations 2001". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on 21 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "6th Annual Excellence in Production Design Awards". Art Directors Guild. Archived from the original on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ "2001 Broadcast Film Critics Choice Award Winners and Nominations". Broadcast Film Critics Choice Awards.com. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Pryor, Fiona (28 September 2007). "Potter wins film awards hat-trick". BBC Online. Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- ^ Griffiths, Peter (10 March 2008). ""Atonement" wins hat-trick of Empire awards". Reuters UK. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2008.

- ^ "Nicholas Hooper nominated for "World Soundtrack Discovery Award"". HPANA. 7 September 2007. Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 8 September 2007.

- ^ "FILM AWARDS NOMINEES IN 2008". BAFTA. 16 January 2008. Archived from the original on 8 February 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ "Film Awards Winners: 2010". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 28 February 2010. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ Orange British Academy Film Awards in 2010 – Long List. Retrieved 5 May 2010.

- ^ "Saturn Awards 2011 Nominations". Saturn Awards. 24 February 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

- ^ "Empire Awards 2011 Best Fantasy Film". Empire Awards. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2011.

You must excuse the absence of David Yates; he'd love to be here but he's putting the finishing touches on our epic finale, which is why I'm here.

- ^ "Saturn Awards 2012 nominees". The Academy of Science Fiction Fantasy & Horror Films. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter becomes highest-grossing film franchise". The Guardian. UK. 11 November 2007. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ^ "Harry-Potter-Deathly-Hallows-–-Part-2" ""Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2" Crosses $1 Billion Threshold" (Press release). Warner Bros. Pictures. 31 July 2011. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1 Conjures International Box Office Magic, Becoming Top Earner of Entire Film Series" (Press release). Warner Bros. Pictures. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ "Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 27 September 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ Etan Vlessing (3 October 2016). "'Harry Potter' Movies Returning to Imax Theaters for One Week". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 9 September 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2016.

- ^ a b Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (2001) at Box Office Mojo

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone – Foreign Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 21 May 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "UK Highest Grossing Movies". 25thframe.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Collett, Mike (22 July 2011). "Harry Potter movies earn $7 billion". msnbc.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (2002) at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets -Foreign Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2004) at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005) at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire -Foreign Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ a b Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007) at Box Office Mojo

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix -Foreign Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2009)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 1 July 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince – Box Office Data". The Numbers. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ^ "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 1". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1 (2010)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ a b Frankel, Daniel (17 November 2010). "Get Ready for the Biggest 'Potter' Opening Yet". The Wrap. Archived from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ a b "All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 10 July 2001. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 2 (2011)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 10 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter Moviesat the Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ Summer 'Potter' Showdown Archived 6 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ a b "The Harry Potter economy". The Economist. 17 December 2009. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Claudia Puig (13 July 2011). "How 'Harry Potter' magically changed films". USA Today. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Graeme McMillan (9 January 2015). "Splitting Tentpole Movies in Two Doesn't Make Them Any More Epic (Opinion)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Costance Grady and Aja Romano (26 June 2017). "How Harry Potter changed the world". Vox. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Harry Potter". "FanFiction.net. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Brown, Kat (2018). "Voldemort: Origins of the Heir review: a fun-free Harry Potter fan film lifted by magical effects". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

External links

- Official website

- Growing Up with Harry Potter – photo essay by Time

- Harry Potter (film series)

- American film series

- BAFTA Outstanding British Contribution to Cinema Award

- British film series

- British ghost films

- Fantasy film series

- Film series based on fantasy novels

- Film series introduced in 2001

- Films about magic

- Films about psychic powers

- Films about witchcraft

- Teen film series

- Warner Bros. Pictures franchises

- Works based on Harry Potter