Hansel and Gretel

| Hansel and Gretel | |

|---|---|

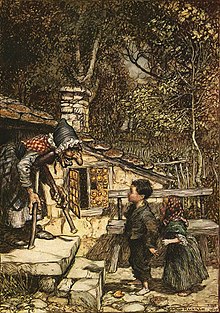

The witch welcomes Hansel and Gretel into her hut. Illustration by Arthur Rackham, 1909. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | Hansel and Gretel |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 327A |

| Region | German |

| Published in | Kinder- und Hausmärchen, by the Brothers Grimm |

"Hansel and Gretel" (/ˈhænsəl, ˈhɛn- ... ˈɡrɛtəl/; German: Hänsel und Gretel [ˈhɛnzl̩ ʔʊnt ˈɡʁeːtl̩])[a] is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm and published in 1812 as part of Grimms' Fairy Tales (KHM 15).[1][2] It is also known as Little Step Brother and Little Step Sister.

Hansel and Gretel are siblings who are abandoned in a forest and fall into the hands of a witch who lives in a bread,[3] cake, and sugar house. The witch, who has cannibalistic intentions, intends to fatten Hansel before eventually eating him. However, Gretel saves her brother by pushing the witch into her own oven, killing her, and escaping with the witch's treasure.[4]

Set in medieval Germany, "Hansel and Gretel" has been adapted into various media, including the opera Hänsel und Gretel by Engelbert Humperdinck, which was first performed in 1893.[5][6]

Origin

[edit]Sources

[edit]Although Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm credited "various tales from Hesse" (the region where they lived) as their source, scholars have argued that the brothers heard the story in 1809 from the family of Wilhelm's friend and future wife, Dortchen Wild, and partly from other sources.[7] A handwritten note in the Grimms' personal copy of the first edition reveals that in 1813 Wild contributed to the children's verse answer to the witch, "The wind, the wind,/ The heavenly child," which rhymes in German: "Der Wind, der Wind,/ Das himmlische Kind."[2]

According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale emerged in the Late Middle Ages Germany (1250–1500). Shortly after this period, close written variants like Martin Montanus' Garten Gesellschaft (1590) began to appear.[4] Scholar Christine Goldberg argues that the episode of the paths marked with stones and crumbs, already found in the French "Finette Cendron" and "Hop-o'-My-Thumb" (1697), represents "an elaboration of the motif of the thread that Ariadne gives Theseus to use to get out of the Minoan labyrinth".[8] A house made of confectionery is also found in a 14th-century manuscript about the Land of Cockayne.[5]

Editions

[edit]

From the pre-publication manuscript of 1810 (Das Brüderchen und das Schwesterchen) to the sixth edition of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Grimm's Fairy Tales) in 1850, the Brothers Grimm made several alterations to the story, which progressively gained in length, psychological motivation, and visual imagery,[9] but also became more Christian in tone, shifting the blame for abandonment from a mother to a stepmother associated with the witch.[1][4]

In the original edition of the tale, the woodcutter's wife is the children's biological mother,[10] but she was also called "stepmother" from the 4th edition (1840).[11][12] The Brothers Grimm indeed introduced the word "stepmother", but retained "mother" in some passages. Even their final version in the 7th edition (1857) remains unclear about her role, for it refers to the woodcutter's wife twice as "the mother" and once as "the stepmother".[2]

The sequence where the duck helps them across the river is also a later addition. In some later versions, the mother died from unknown causes, left the family, or remained with the husband at the end of the story.[13] In the 1810 pre-publication manuscript, the children were called "Little Brother" and "Little Sister", then named Hänsel and Gretel in the first edition (1812).[9] Wilhelm Grimm also adulterated the text with Alsatian dialects, "re-appropriated" from August Stöber's Alsatian version (1842) in order to give the tale a more "folksy" tone.[11][b]

Goldberg notes that although "there is no doubt that the Grimms' Hänsel und Gretel was pieced together, it was, however, pieced together from traditional elements," and its previous narrators themselves had been "piecing this little tale together with other traditional motifs for centuries."[14] For instance, the duck helping the children cross the river may be the remnant of an old traditional motif in the folktale complex that was reintroduced by the Grimms in later editions.[14]

Plot

[edit]

Hansel and Gretel are the young children of a poor woodcutter. When a famine settles over the land, the woodcutter's second wife tells him to take the children into the woods and leave them there to fend for themselves. The woodcutter opposes the plan, but his wife repeats her demands until he reluctantly agrees. They are unaware that in the children's bedroom, Hansel and Gretel have overheard them. After the parents have gone to bed, Hansel sneaks out of the house and gathers as many shiny white pebbles as he can, then returns to his room, reassuring Gretel that God will not forsake them.

The next day, the children's stepmother gives them small pieces of bread before she and their father take them into the woods. As the family walks deeper, Hansel leaves a trail of white pebbles. After their parents abandon them, the children stay in the woods until night falls and the moonlight reveals the white pebbles shining in the dark. The children then safely follow the trail back home, much to their stepmother's rage. Once again, provisions become scarce and the stepmother angrily orders her husband to take the children further into the woods and leave them there. Hansel attempts to gather more pebbles, but finds his stepmother has locked the door.

The following morning, the children's stepmother gives them smaller pieces of bread, before she and their father take them back into the woods. As the family treks, Hansel leaves a trail of bread crumbs for him and Gretel to follow back home. However, after they are once again abandoned, the children find that the birds have eaten the crumbs and they are lost in the woods. After three days of wandering, the children follow a dove to a clearing in the woods, and discover a cottage with bread walls, a cake roof, and sugar windows. Hungry and tired, the children begin to eat the house, when the door opens and the elderly woman that lives there emerges and takes the children inside, giving them delicious food to eat and soft beds to sleep in. What the children do not know is that their kind hostess is an evil witch who had built the bread house to lure them inside so she can cook and eat them.

The next morning, the witch locks Hansel in a stable and enslaves Gretel. The witch feeds Hansel regularly to fatten him up, but serves Gretel nothing but crab shells. The witch then tries to touch Hansel's finger to see how fat he has become, but he cleverly offers a thin bone he found in the cage. As the witch's eyes are too weak to notice the deception, she is fooled into thinking Hansel is still too thin for her to eat. After four weeks of this, the witch grows impatient and decides to eat Hansel anyway.

She prepares the oven for Hansel, but decides she is hungry enough to eat Gretel, too. She coaxes Gretel to the open oven and asks her to lean over in front of it to see if the fire is hot enough. Gretel, sensing the witch's intent, pretends she does not understand what the witch means. Frustrated, the witch demonstrates, and Gretel instantly shoves her into the hot oven, slams and bolts the door shut, leaving the witch to burn to death. Gretel frees Hansel from the stable and the pair discover boxes full of pearls and precious stones. Putting the jewels into their pockets, the children set off for home. A white duck (or swan in some versions) ferries them across an expanse of water, and at home they find only their father; his wife had died from an unknown cause. The children's father had spent all his days missing them, and is delighted to see them safe and sound.

With the witch's wealth, the children and their father all live happily ever after.

Variants

[edit]

Folklorists Iona and Peter Opie indicate that "Hansel and Gretel" belongs to a group of European tales especially popular in the Baltic regions, about children outwitting ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen.[5]

ATU 327A tales

[edit]"Hansel and Gretel" is the prototype for the fairy tales of the type Aarne–Thompson–Uther (ATU) 327A. In particular, Gretel's pretense of not understanding how to test the oven ("Show Me How") is characteristic of 327A, although it also appears traditionally in other sub-types of ATU 327.[15] As argued by Stith Thompson, the simplicity of the tale may explain its spread into several traditions all over the world.[16]

A closely similar version is "Finette Cendron", published by Marie-Catherine d'Aulnoy in 1697, which depicts an impoverished king and queen deliberately losing their three daughters three times in the wilderness. The cleverest of the girls, Finette, initially manages to bring them home with a trail of thread, and then a trail of ashes, but her peas are eaten by pigeons during the third journey. The little girls then go to the mansion of a hag, who lives with her husband the ogre. Finette heats the oven and asks the ogre to test it with his tongue, so that he falls in and is incinerated. Thereafter, Finette cuts off the hag's head. The sisters remain in the ogre's house, and the rest of the tale relates the story of Cinderella.[5][8]

In the Russian Vasilisa the Beautiful, the stepmother likewise sends her hated stepdaughter into the forest to borrow a light from her sister, who turns out to be Baba Yaga, a cannibalistic witch. Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the tales have in common a preoccupation with eating and with hurting children: The mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, and the witch lures children to eat her house of candy so that she can then eat them.[17]

In a variant from Flanders, The Sugar-Candy House, siblings Jan and Jannette get lost in the woods and sight a hut made of confectionery in the distance. When they approach, a giant wolf named Garon jumps out of the window and chases them to a river bank. Sister and brother ask a pair of ducks to help them cross the river and escape the wolf. Garon threatens the ducks to carry him over, to no avail; he then tries to cross by swimming. He sinks and surfaces three times, but disappears in the water on the fourth try. The story seems to contain the "child/wind" rhyming scheme of the German tale.[18]

In a French fairy tale, La Cabane au Toit de Fromage ("The Hut with the Roof made of Cheese"), the brother is the hero who deceives the witch and locks her up in the oven.[19]

In the first Puerto Rican variant of "The Orphaned Children", the brother pushes the witch into the oven.[20]

Other folk tales of ATU 327A type include the French "The Lost Children", published by Antoinette Bon in 1887,[21][22] or the Moravian "Old Gruel", edited by Maria Kosch in 1899.[22]

The Children and the Ogre (ATU 327)

[edit]Structural comparisons can also be made with other tales of ATU 327 type ("The Children and the Ogre"), which is not a simple fairy tale type but rather a "folktale complex with interconnected subdivisions" depicting a child (or children) falling under the power of an ogre, then escaping by their clever tricks.[23]

In ATU 327B ("The Brothers and the Ogre"), a group of siblings come to an ogre's house who intends to kill them in their beds, but the youngest of the children exchanges the visitors with the ogre's offspring, and the villain kills his own children by mistake. They are chased by the ogre, but the siblings eventually manage to come back home safely.[24] Stith Thompson points the great similarity of the tales types ATU 327A and ATU 327B that "it is quite impossible to disentangle the two tales".[25]

ATU 327C ("The Devil [Witch] Carries the Hero Home in a Sack") depicts a witch or an ogre catching a boy in a sack. As the villain's daughter is preparing to kill him, the boy asks her to show him how he should arrange himself; when she does so, he kills her. Later on, he kills the witch and goes back home with her treasure. In ATU 327D ("The Kiddlekaddlekar"), children are discovered by an ogre in his house. He intends to hang them, but the girl pretends not to understand how to do it, so the ogre hangs himself to show her. He promises his kiddlekaddlekar (a magic cart) and treasure in exchange for his liberation; they set him free, but the ogre chases them. The children eventually manage to kill him and escape safely. In ATU 327F ("The Witch and the Fisher Boy"), a witch lures a boy and catches him. When the witch's daughter tries to bake the child, he pushes her into the oven. The witch then returns home and eats her own daughter. She eventually tries to fell the tree in which the boy is hiding, but birds fly away with him.[24]

Further comparisons

[edit]The initial episode, which depicts children deliberately lost in the forest by their unloving parents, can be compared with many previous stories: Montanus's "The Little Earth-Cow" (1557), Basile's "Ninnillo and Nennella" (1635), Madame d'Aulnoy's "Finette Cendron" (1697), or Perrault's "Hop-o'-My-Thumb" (1697). The motif of the trail that fails to lead the protagonists back home is also common to "Ninnillo and Nennella", "Finette Cendron" and "Hop-o'-My-Thumb",[26] and the Brothers Grimm identified the latter as a parallel story.[27]

Finally, ATU 327 tales share a similar structure with ATU 313 ("Sweetheart Roland", "Foundling-Bird", "Okerlo") in that one or more protagonists (specifically children in ATU 327) come into the domain of a malevolent supernatural figure and escape from it.[24] Folklorist Joseph Jacobs, commenting on his reconstructed proto-form of the tale ("Johnnie and Grizzle"), noticed the "contamination" of the tale with the story of "The Master Maid", later classified as ATU 313.[28] ATU 327A tales are also often combined with stories of ATU 450 ("Little Brother and Sister"), in which children run away from an abusive stepmother.[4]

Analysis

[edit]According to folklorist Jack Zipes, the tale celebrates the symbolic order of the patriarchal home, seen as a haven protected from the dangerous characters that threaten the lives of children outside, while it systematically denigrates the adult female characters, which are seemingly intertwined between each other.[6][29] The death of the mother or stepmother soon after the children kill the witch suggests that they may be metaphorically the same woman.[30] Zipes also argues that the importance of the tale in the European oral and literary tradition may be explained by the theme of child abandonment and abuse. Due to famines and lack of birth control, it was common in medieval Europe to abandon unwanted children in front of churches or in the forest. The death of the mother during childbirth sometimes led to tensions after remarriage, and Zipes proposes that it may have played a role in the emergence of the motif of the wicked stepmother.[29]

Linguist and folklorist Edward Vajda has proposed that these stories represent the remnant of a coming-of-age, rite of passage tale extant in Proto-Indo-European society.[31][32] Psychologist Bruno Bettelheim argues that the main motif revolves around dependence, oral greed, and destructive desires that children must learn to overcome, after they arrive home "purged of their oral fixations". Others have stressed the satisfying psychological effects of the children vanquishing the witch or realizing the death of their wicked stepmother.[6]

Cultural legacy

[edit]

Stage and musical theater

[edit]The fairy tale has spawned a multitude of adaptations for the stage, with one of the most notable being Engelbert Humperdinck's opera Hänsel und Gretel.[33] It is primarily based upon the Grimm's version, although it omits the deliberate abandonment of the children,[5][6] and is notable for kickstarting the adaptions depicting the witch's house being made of gingerbread and candy instead of plain bread.

A contemporary reimagining of the story, Mátti Kovler's musical fairytale Ami & Tami, was produced in Israel and the United States and subsequently released as a symphonic album.[34][35]

Literature

[edit]Several writers have drawn inspiration from the tale, such as Robert Coover in "The Gingerbread House" (Pricksongs and Descants, 1969), Anne Sexton in Transformations (1971), Garrison Keillor in "My Stepmother, Myself" in "Happy to Be Here" (1982), and Emma Donoghue in "A Tale of the Cottage" (Kissing the Witch, 1997).[6] Adam Gidwitz's 2010 children's book A Tale Dark & Grimm and its sequels In a Glass Grimmly (2012), and The Grimm Conclusion (2013) are loosely based on the tale and show the siblings meeting characters from other fairy tales. Terry Pratchett mentions gingerbread cottages in several of his books, mainly where a witch had turned wicked and 'started to cackle', with the gingerbread house being a stage in a person's increasing levels of insanity. In The Light Fantastic, the wizard Rincewind and Twoflower are led by a gnome into one such building after the death of the witch and warned to be careful of the doormat, as it is made of candy floss. In 2014, Neil Gaiman wrote an expanded retelling of "Hansel and Gretel", with illustrations by Lorenzo Mattotti.[36]

Film and television

[edit]- Hansel and Gretel: An Opera Fantasy, a 1954 stop-motion animated theatrical feature film directed by John Paul and released by RKO Radio Pictures.

- The Bewitched episode "Hansel and Gretel in Samanthaland" has Tabitha Stephens magically switching places with Hansel and Gretel, and her mother, Samantha, entering the fairy tale to rescue her from the child-eating witch. The episode features Bobo Lewis as the stepmother, Billie Hayes as the witch, and Richard X. Slattery as a policeman.

- A 1983 episode of Shelley Duvall's Faerie Tale Theatre starred Ricky Schroder as Hansel and Joan Collins as the stepmother/witch.

- The story was adapted into a Grimm's Fairy Tale Classics episode; while mostly faithful to the original source material, it depicts the witch as transforming into a scary winged skeletal monster before the protagonists trick her into flying into her burning oven and sealing her in it.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1983 TV special directed by Tim Burton.

- Hansel and Gretel, a 1987 American/Israeli musical film directed by Len Talan with David Warner, Cloris Leachman, Hugh Pollard and Nicola Stapleton. Part of the 1980s film series Cannon Movie Tales.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1994 horror film Wes Craven's New Nightmare for its climax.

- A Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child episode puts a Latin American spin on the fairy tale and renames the protagonists "Hanselito" and "Gretelita". This adaptation features the voices of Cheech Marin as the Father, Liz Torres as the Stepmother, and Rosie Perez as the Witch.

- Elements from the story were used in the 1999 black comedy film Freeway II: Confessions of a Trickbaby.[37]

- In The Grim Adventures of Billy & Mandy episode segment "Nursery Crimes", Grim transports Billy and Mandy into an enchanted book to make them play the eponymous "Hansel and Gretel" in his own telling, which goes awry with the duo deviating from the plot and interacting with other fairy tale characters instead.

- In 2012, the German broadcaster RBB released an episode "Hänsel und Gretel" as part of its series Der rbb macht Familienzeit.[38]

- Hansel & Gretel: Witch Hunters (2013) by Tommy Wirkola with Jeremy Renner and Gemma Arterton, (USA, Germany). The film follows the adventures of Hansel and Gretel who became adults.

- Gretel & Hansel, a 2020 American horror film directed by Oz Perkins in which Gretel is a teenager while Hansel is still a little boy.

- Secret Magic Control Agency (2021) is an animated retelling of the fairy tale by incorporating comedy and family genres.[39]

- A Tale Dark & Grimm (2021) is a Netflix computer-animated series based on the novel of the same name by Adam Gidwitz, which, in turn, is a loose retelling of the story mixed with other Grimm fairy tales.

- The Grimm Variations (2024) is a Netflix anime series which features a retelling of the story featuring elements of science fiction.

Computer programming

[edit]Hansel and Gretel's trail of breadcrumbs inspired the name of the navigation element breadcrumbs that allows users to keep track of their locations within programs or documents.[40]

Video games

[edit]- Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle (1995) by Terraglyph Interactive Studios is an adventure and hidden object game. The player controls Hansel, tasked with finding Prin, a forest imp, who holds the key to saving Gretel from the witch.[41]

- Gretel and Hansel (2009) by Mako Pudding is a browser adventure game. Popular on Newgrounds for its gruesome reimagining of the story, it features hand painted watercolor backgrounds and characters animated by Flash.[42]

- Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector's Edition (2013) by Eipix Entertainment is a HOPA (hidden object puzzle adventure) game. The player, as Hansel and Gretel's mother, searches the witch's lair for clues.[43]

- In the online role-playing game Poptropica, the Candy Crazed mini-quest (2021) includes a short retelling of the story. The player is summoned to the witch's castle to free the children, who have been imprisoned after eating some of the candy residents.[44]

See also

[edit]- "Brother and Sister"

- Child cannibalism

- "Esben and the Witch"

- Gingerbread house

- "Hop-o'-My-Thumb" (French fairy tale by Charles Perrault)

- "The Hut in the Forest"

- "Ivasyk-Telesyk"

- "Jorinde and Joringel"

- "Molly Whuppie"

- "The Restaurant of Many Orders" (Japanese short story by Kenji Miyazawa)

- "Thirteenth"

- The Truth About Hansel and Gretel

Footnotes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Harries 2015, p. 225.

- ^ a b c Ashliman, D. L. (2011). "Hansel and Gretel". University of Pittsburgh.

- ^ Heiner, Heidi Anne (2021). "Hansel & Gretel Annotations". Sur La Lune.

- ^ a b c d Zipes 2013, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236.

- ^ a b c d e Harries 2015, p. 227.

- ^ Opie & Opie 1974, p. 236; Goldberg 2000, p. 42; Harries 2015, p. 225; Zipes 2013, p. 121

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 439.

- ^ a b Goldberg 2008, p. 438.

- ^ Zipes (2014) tr. "Hansel and Gretel (The Complete First Edition)", pp. 43–48; Zipes (2013) tr., pp. 122–126; Brüder Grimm, ed. (1812). . Kinder- und Haus-Märchen (in German). Vol. 1 (1 ed.). Realschulbuchhandlung. pp. 49–58 – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, p. 438: "in the fourth edition, the woodcutter's wife (who had been the children's own mother) was first called a stepmother."

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 45

- ^ a b Goldberg 2000, p. 51.

- ^ Goldberg 2008, pp. 439–440.

- ^ Thompson 1977, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 54

- ^ Bosschère, Jean de. Folk tales of Flanders. New York: Dodd, Mead. 1918. pp. 91-94.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. Contes et légendes. 1ere partie. New York, Cincinnati [etc.] American book company. 1895. pp. 64-67.

- ^ Ocasio, Rafael (2021). Folk stories from the hills of Puerto Rico = Cuentos folklóricos de las montañas de Puerto Rico. New Brunswick. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1978823013.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Delarue 1956, p. 365.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, pp. 146, 150.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, pp. 43.

- ^ a b c Goldberg 2008, p. 441.

- ^ Thompson 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Goldberg 2000, p. 44.

- ^ Tatar 2002, p. 72

- ^ Jacobs 1916, pp. 255–256.

- ^ a b Zipes 2013, p. 122.

- ^ Lüthi 1970, p. 64

- ^ Vajda 2010

- ^ Vajda 2011

- ^ Upton, George P. (2011). The Standard Operas - Their Plots, Their Music, and Their Composers. Plain Label Books. pp. 125–129. ISBN 978-1-60303-367-1.

- ^ "Composer Matti Kovler realizes dream of reviving fairy-tale opera in Boston". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Schwartz, Penny. "Boston goes into the woods with Israeli opera 'Ami and Tami'". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (2014). Hansel & Gretel. Toon Books.

- ^ "Freeway II: Confessions of a Trickbaby". The A.V. Club. 29 March 2002.

- ^ "Hänsel und Gretel | Der rbb macht Familienzeit – YouTube". www.youtube.com. Archived from the original on 2021-10-30. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- ^ Milligan, Mercedes (2019-11-01). "Wizart Reveals 'Hansel and Gretel' Poster Art Ahead of AFM". Animation Magazine. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ^ Page 221 in: Levene, Mark (2010). "Navigating the Web". An Introduction to Search Engines and Web Navigation. pp. 209–271. doi:10.1002/9780470874233.ch7. ISBN 978-0-470-52684-2.

- ^ "Hansel & Gretel and the Enchanted Castle for Windows (1995)".

- ^ "Gretel and Hansel".

- ^ "Fearful Tales: Hansel and Gretel Collector's Edition for iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac & PC! Big Fish is the #1 place for the best FREE games".

- ^ "The Candy Crazed Mini Quest is NOW LIVE!! 🍬🏰 | poptropica". 9 May 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Delarue, Paul (1956). The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales. Alfred A. Knopf.

- Goldberg, Christine (2000). "Gretel's Duck: The Escape from the Ogre in AaTh 327". Fabula. 41 (1–2): 42–51. doi:10.1515/fabl.2000.41.1-2.42. S2CID 163082145.

- Goldberg, Christine (2008). "Hansel and Gretel". In Haase, Donald (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-04947-7.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). European Folk and Fairy Tales. G. P. Putnam's sons.

- Lüthi, Max (1970). Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales. Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. ISBN 9780804425650.

- Opie, Iona; Opie, Peter (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-211559-1.

- Tatar, Maria (2002). The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales. BCA. ISBN 978-0-393-05163-6.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03537-9.

- Vajda, Edward (2010). The Classic Russian Fairy Tale: More Than a Bedtime Story (Speech). The World's Classics. Western Washington University.

- Vajda, Edward (2011). The Russian Fairy Tale: Ancient Culture in a Modern Context (Speech). Center for International Studies International Lecture Series. Western Washington University.

- Harries, Elizabeth Wanning (2015). "Hansel and Gretel". In Zipes, Jack (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Fairy Tales. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199689828.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-968982-8.

- Zipes, Jack (2013). "Abandoned Children ATU 327A―Hansel and Gretel". The Golden Age of Folk and Fairy Tales: From the Brothers Grimm to Andrew Lang. Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 121ff. ISBN 978-1-624-66034-4.

Primary sources

[edit]- Zipes, Jack (2014). "Hansel and Gretel (Hänsel und Gretel)". The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition. Jacob Grimm; Wilhelm Grimm (orig. eds.); Andrea Dezsö (illustr.) (Revised ed.). Princeton University Press. pp. 43–48. ISBN 978-0-691-17322-1.

Further reading

[edit]- de Blécourt, Willem (April 2008). "On the Origin of Hänsel und Gretel". Fabula. 49 (1–2): 30–46. doi:10.1515/FABL.2008.004.

- Böhm-Korff, Regina (1991). Deutung und Bedeutung von 'Hänsel und Gretel': eine Fallstudie (in German). P. Lang. ISBN 978-3-631-43703-2.

- Freudenburg, Rachel (1998). "Illustrating Childhood—'Hansel and Gretel'". Marvels & Tales. 12 (2): 263–318. JSTOR 41388498.

- Gaudreau, Jean (1990). "Handicap et sentiment d'abandon dans trois contes de fées : Le petit Poucet, Haensel et Gretel, Jean-mon-Hérisson". Enfance. 43 (4): 395–404. doi:10.3406/enfan.1990.1957.

- Harshbarger, Scott (2013). "Grimm and Grimmer: 'Hansel and Gretel' and Fairy Tale Nationalism". Style. 47 (4): 490–508. JSTOR 10.5325/style.47.4.490.

- Mieder, Wolfgang (2007). Hänsel und Gretel: das Märchen in Kunst, Musik, Literatur, Medien und Karikaturen (in German). Praesens. ISBN 978-3-7069-0469-8.

- Taggart, James M. (October 1986). "'Hansel and Gretel' in Spain and Mexico". The Journal of American Folklore. 99 (394): 435. doi:10.2307/540047. JSTOR 540047.

- Zipes, Jack (1997). "The rationalization of abandonment and abuse in fairy tales: The case of Hansel and Gretel". Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales, Children, and the Culture Industry. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-25296-0.

External links

[edit]- Hansel and Gretel at Project Gutenberg

- Hansel and Gretel – the original version by the Brothers Grimm

- Annotated Hansel and Gretel

- The complete set of Grimms' Fairy Tales, including Hansel and Gretel at Standard Ebooks

- Illustrations to Hansel and Gretel

- Hansel and Gretel

- Fiction about cannibalism

- European fairy tales

- Grimms' Fairy Tales

- Literary duos

- Child characters in fairy tales

- Male characters in fairy tales

- Female characters in fairy tales

- Fictional German people

- Witchcraft in fairy tales

- European folklore characters

- German fairy tales

- Fiction about siblings

- Germany in fiction

- Works about dysfunctional families

- ATU 300-399

- Works about child abuse

- Child abandonment

- Child abduction in folklore

- Fiction set in the Middle Ages

- Ariadne

- Late Middle Ages