Wilhelm Busch

Wilhelm Busch | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1894 | |

| Born | Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch 14 April 1832[1][2][a] Wiedensahl, Kingdom of Hanover (today Lower Saxony) |

| Died | 9 January 1908 (aged 75) Mechtshausen, Province of Hanover, German Empire (today part of Seesen, Lower Saxony) |

| Education | Hannover Polytechnic, Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, Beaux-Arts Academy, Antwerp, Academy of Fine Arts, Munich |

| Genre | Caricature, painting, poetry |

| Notable works | Max and Moritz |

| Signature | |

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (14 April 1832 – 9 January 1908) was a German humorist, poet, illustrator, and painter. He published wildly innovative illustrated tales that remain influential to this day.

Busch drew on the tropes of folk humour as well as a profound knowledge of German literature and art to satirize contemporary life, any kind of piety, Catholicism, Philistinism, religious morality, bigotry, and moral uplift.

His mastery of drawing and verse became deeply influential for future generations of comic artists and vernacular poets. Among many notable influences, The Katzenjammer Kids was inspired by Busch's Max and Moritz. Today, the Wilhelm Busch Prize and the Wilhelm Busch Museum help maintain his legacy. The 175th anniversary of his birth in 2007 was celebrated throughout Germany. Busch remains one of the most influential poets and artists in Western Europe, being called the "Forefather of Comics".[3]

Family background

[edit]

Johann Georg Kleine, Wilhelm Busch's maternal grandfather, settled in the small village of Wiedensahl, where in 1817 he bought a thatched half-timbered house where Wilhelm Busch was to be born 15 years later. Amalie Kleine, Johann's wife and Wilhelm Busch's grandmother, kept a shop where Busch's mother Henriette assisted while her two brothers attended high school. When Johann Georg Kleine died in 1820, his widow continued to run the shop with Henriette.[4][5][6]

At the age of 19 Henriette Kleine married surgeon Friedrich Wilhelm Stümpe.[7] Henriette became widowed at the age of 26, with her three children to Stümpe dying as infants. About 1830 Friedrich Wilhelm Busch, the illegitimate son of a farmer, settled in Wiedensahl after completing a business apprenticeship in the nearby village of Loccum. He took over the Kleine shop in Wiedensahl, which he completely modernised.[8] He married Henriette Kleine Stümpe.

Life

[edit]Childhood

[edit]Wilhelm Busch was born on 14 April 1832,[1][2][a] the first of seven children to Henriette Kleine Stümpe and Friedrich Wilhelm Busch. His six siblings followed shortly after: Fanny (1834), Gustav (1836), Adolf (1838), Otto (1841), Anna (1843), and Hermann (1845); all survived childhood. His parents were ambitious, hard-working and devout Protestants who later, despite becoming relatively prosperous, could not afford to educate all three sons.[9] Busch's biographer Berndt W. Wessling suggested that Friedrich Wilhelm Busch invested heavily in the education of his sons partly because his own illegitimacy held significant stigma in rural areas.[10]

The young Wilhelm Busch was a tall child, with a delicate physique. The coarse boyishness of his later protagonists, "Max and Moritz" was not his own. He described himself in autobiographical sketches and letters as sensitive and timid, someone who "carefully studied fear",[11] and who reacted with fascination, compassion, and distress when animals were killed in the autumn.[11] He described the "transformation to sausage" as "dreadfully compelling",[12][13] leaving a lasting impression; pork nauseated him throughout his life.[14]

In the autumn of 1841, after the birth of his brother Otto, Busch's education was entrusted to the 35-year-old clergyman, Georg Kleine, his maternal uncle at Ebergötzen, where 100 children were taught within a space of 66 m2 (710 sq ft).[15] This probably through lack of space in the Busch family home, and his father's desire for a better education than the small local school could provide. The nearest convenient school was located in Bückeburg, 20 km (12 mi) from Wiedensahl. Kleine, with his wife Fanny Petri, lived in a rectory at Ebergötzen, while Busch was lodged with an unrelated family. Kleine and his wife were responsible and caring, exercised a substitute parental role, and provided refuge for him in future unsuccessful times.[16][17]

Kleine's private lessons for Busch also were attended by Erich Bachmann, the son of a wealthy Ebergötzen miller. Both became friends, according to Busch the strongest friendship of his childhood. This friendship was echoed in the 1865 story, Max and Moritz. A small pencil portrait by the 14-year-old Busch depicted Bachmann as a chubby, confident boy, and showed similarities with Max. Busch portrayed himself with a "cowlick", in the later "Moritzian" perky style.[18]

Kleine was a philologist, his lessons not held in contemporary language, and it is not known for certain all subjects Busch and his friend were taught. Busch did learn elementary arithmetic from his uncle, although science lessons might have been more comprehensive, as Kleine, like many other clergymen, was a beekeeper, and published essays and textbooks on the subject,[19][20] – Busch demonstrated his knowledge of bee-keeping in his future stories. Drawing, and German and English poetry, were also taught by Kleine.[21]

Busch had little contact with his natural parents during this period. At the time, the 165 km (103 mi) journey between Wiedensahl and Ebergötzen took three days by horse.[22] His father visited Ebergötzen two to three times a year, while his mother stayed in Wiedensahl to look after the other children. The 12-year-old Busch visited his family once; his mother at first did not recognize him.[23] Some Busch biographers think that this early separation from his parents, especially from his mother, resulted in his eccentric bachelorhood.[24][25] In the autumn of 1846, Busch moved with the Kleines to Lüthorst, where, on 11 April 1847, he was confirmed.[26]

Study

[edit]In September 1847 Busch began studying mechanical engineering at Hannover Polytechnic. Busch's biographers are not in agreement as to why his Hanover education ended; most believe that his father had little appreciation of his son's artistic inclination.[27] Biographer Eva Weissweiler suspects that Kleine played a major role, and that other possible causes were Busch's friendship with an innkeeper, Brümmer, political debates in Brümmer's tavern, and Busch's reluctance to believe every word of the Bible and catechism.[28]

Busch studied for nearly four years at Hanover, despite initial difficulties in understanding the subject matter. A few months before graduation he confronted his parents with his aspiration to study at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. According to Bush's nephew Hermann Nöldeke, his mother supported this inclination.[29] His father eventually acquiesced and Busch moved to Düsseldorf in June 1851,[30] where, to his disappointment at not being admitted to the advanced class, he entered preparatory classes.[31] Busch's parents had his tuition fees paid for one year, so in May 1852 he traveled to Antwerp to continue study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts under Josephus Laurentius Dyckmans. He led his parents to believe that the academy was less regimented than Düsseldorf, and had the opportunity to study Old Masters.[32] At Antwerp he saw for the first time paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, Adriaen Brouwer, David Teniers, and Frans Hals.[33] The pictures aroused his interest, but made him doubt his own skills.[34] Eventually, in 1853, after suffering heavily from typhus, he abandoned his Antwerp studies and returned penniless to Wiedensahl.[35]

Munich

[edit]Busch was ravaged by disease, and for five months spent time painting and collecting folk tales, legends, songs, ballads, rhymes, and fragments of regional superstitions.[36] Busch's biographer, Joseph Kraus, saw these collections as useful additions to folklore, as Busch noted the narrative background to tales and the idiosyncrasies of storytellers.[37] Busch tried to release the collections, but as a publisher could not be found at the time, they were issued after his death. During the Nazi era Busch was known as an "ethnic seer".[36]

After Busch had spent six months with his uncle Kleine at Lüthorst, he expressed a desire to continue to study in Munich. This request caused a rift with his father who, however, eventually funded this move;[38] – see for comparison Busch's illustrated story of Painter Klecksel. Busch's expectations of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts were not met. His life became aimless; there were occasional return visits to Lüthorst, but contact with his parents had been broken off.[39] In 1857 and 1858, as his position seemed to be without prospects, he contemplated emigration to Brazil to keep bees.[40]

Busch made contact with the artist association, Jung München (Young Munich), met several notable Munich artists, and wrote and provided cartoons for the Jung München newspaper.[41] Kaspar Braun, who published the satirical newspapers, Münchener Bilderbogen (Picture Sheets from Munich) and Fliegende Blätter (Flying Leaves), proposed a collaboration with Busch.[42] This association provided Busch with sufficient funds to live. An existing self-caricature suggests that at this time he had an intense relationship with a woman from Ammerland.[43] His courtship with a seventeen-year-old merchant's daughter, Anna Richter, whom Busch met through his brother Gustav, ended in 1862. Busch's biographer, Diers, suggests that her father probably refused to entrust his daughter to an almost unknown artist without regular income.[44]

In his early Munich years Busch's attempts to write libretti, which are almost forgotten today, were unsuccessful. Up to 1863 he worked on two or three major works; the third was composed by Georg Kremplsetzer. Busch's Liebestreu und Grausamkeit, a romantic opera in three acts, Hansel und Gretel, and Der Vetter auf Besuch, an opera buffa of sorts, were not particularly successful. There was a dispute between Busch and Kremplsetzer during the staging of Der Vetter auf Besuch, leading to the removal of Busch's name from the production; the piece was renamed, Singspiel von Georg Kremplsetzer.[45] However, German composer Elsa Laura Wolzogen set several of his poems to music.

In 1873 Busch returned several times to Munich, and took part in the intense life of the Munich Art Society as an escape from provincial life.[46] In 1877, in a last attempt to be a serious artist, he took a studio in Munich.[46] He left Munich abruptly in 1881, after he disrupted a variety show and subsequently made a scene through the effects of alcohol.[47] The 1878 nine episode illustrated tale Eight Sheets in the Wind describes how humans behave like animals when drunk. Busch's biographer Weissweiler felt the story was only superficially funny and harmless, but was a study on addiction and its induced state of delusion.[48]

Publication of Max and Moritz

[edit]

Between 1860 and 1863 Busch wrote more than one hundred articles for the Münchener Bilderbogen and Fliegende Blätter, but he felt his dependence on publisher Kaspar Braun had become constricting. Busch appointed Dresden publisher Heinrich Richter, the son of Saxon painter Ludwig Richter, as his new publisher – Richter's press up to that time was producing children's books and religious Christian devotional literature.[49] Busch could choose themes, although Richter raised some concerns regarding four suggested illustrated tales that were proposed. However, some were published in the 1864 as Bilderpossen, proving a failure. Busch then offered Richter the manuscripts of Max and Moritz, waiving any fees. Richter rejected the manuscript as sales prospects seemed poor. Busch's former publisher, Braun, purchased the right to Max and Moritz for 1,000 gulden, corresponding to approximately double the annual wage of a craftsman.[50]

For Braun the manuscript was fortuitous.[50] Initially the sales of Max and Moritz were slow, but sales figures improved after the 1868 second edition. Overall there were 56 editions and more than 430,000 copies sold up to Busch's death in 1908.[51] Despite at first being ignored by critics, teachers in the 1870s described Max and Moritz as frivolous and an undesirable influence on the moral development of young people.[52]

Frankfurt

[edit]Increasing economic success allowed Busch to visit Wiedensahl more frequently. Busch had decided to leave Munich, as only few relatives lived there and the artist association was temporarily disbanded.[53] In June 1867 Busch met his brother Otto for the first time, in Frankfurt. Otto was working as a tutor to the family of a wealthy banker and industrialist, Kessler. Busch became friends with Kessler's wife, Johanna, a mother of seven and an influential art and music patron of Frankfurt. She regularly opened salons at her villa, frequented by artists, musicians, and philosophers.[54] She believed Busch to be a great painter, a view supported by Anton Burger, a leading painter of the Kronberger Malerkolonie, the Kronberg-based group of painters.[55] While his humorous drawings did not appeal to her, she supported his painting career. At first she established an apartment and studio for Busch in her villa, later providing him with an apartment nearby.[56] Motivated by Kessler's support and admiration, and introduction to the cultural life of Frankfurt, the 'Frankfurter Years' were the most artistically productive for Busch. At this time he and Otto discovered the philosophical works of Arthur Schopenhauer.[57]

Busch did not remain in Frankfurt. Toward the end of the 1860s he alternated between Wiedensahl and Lüthorst, and Wolfenbüttel where his brother Gustav lived.[58] The association with Johanna Kessler lasted five years, and after his return to Wiedensahl in 1872 they communicated by letter. This contact was interrupted between 1877 and 1891, after which it was revived with the help of Kessler's daughters.[59]

Later life

[edit]

Biographer Weissweiler does not dismiss the possibility that Busch's increasing alcohol dependence hindered self-criticism.[60] He refused invitations to parties, and publisher Otto Bassermann sent him to Wiedensahl to keep his alcohol problem undetected from those around him. Busch was also a heavy smoker, resulting in symptoms of severe nicotine poisoning in 1874. He began to illustrate drunkards more often.[60]

Dutch writer Marie Anderson corresponded with Busch. More than fifty letters were exchanged between January and October 1875 in which they discussed philosophy, religion, and ethics.[61] Although only one Anderson letter survives, Busch's letters are in manuscripts.[62] They met in Mainz in October 1875, after which he returned to Bassermann at Heidelberg in a "horrible mood". According to several people at the time, Busch's failure to find a wife was responsible for his conspicuous behaviour. There is no evidence that Busch had a close relationship with any woman after that with Anderson.[63]

Busch lived with his sister Fanny's family after her husband Pastor Hermann Nöldeke's death in 1879. His nephew Adolf Nöldeke remembers that Busch wanted to move back to Wiedensahl with the family.[64] Busch renovated the house, which Fanny looked after even though Busch was a rich man,[65] and became "father" to his three young nephews. She would, however, have preferred to live in a more urban area for the education of her sons. For Fanny and her three sons, Busch could not replace their former idyllic life. The years around 1880 were psychically and emotionally exhausting for Busch, who was still reliant on alcohol. He would not invite visitors to Wiedensahl; because of this Fanny lost contact with her friends in the village,[65] and whenever she questioned his wishes, Busch became furious.[66] Even his friends Otto Friedrich Bassermann, Franz von Lenbach, Hermann Levi and Wilhelm von Kaulbach were not welcome at the house; he would meet them in Kassel or Hanover.

Busch stopped painting in 1896 and signed over all publication rights to Bassermann Verlag for 50,000 gold marks.[67] Busch, now aged 64, felt old. He needed spectacles for writing and painting, and his hands trembled slightly. In 1898, together with his aging sister Fanny Nöldeke, he accepted Bassermann's suggestion to move into a large parsonage in Mechtshausen.[68] Busch read biographies, novels and stories in German, English and French. He organized his works and wrote letters and poems. Most of the poems from the collections Schein und Sein and Zu guter Letzt were written in 1899.[69] The following years were eventless for Busch.

He developed a sore throat in early January 1908, and his doctor detected a weak heart. During the night of 8–9 January 1908 Busch slept uneasily, taking camphor, and a few drops of morphine as a tranquilizer. Busch died the following morning before his physician, called by Otto Nöldeke, came to assist.[70]

Work

[edit]

During the Frankfurt period Busch published three self-contained illustrated satires. Their anti-clerical themes proved popular during the Kulturkampf.[71] Busch's satires typically did not address political questions, but exaggerated churchiness, superstition, and philistine double standards. This exaggeration made at least two of the works historically erroneous.[72] The third illustrated satire, Father Filucius (Pater Filucius), described by Busch as an "allegorical mayfly", has greater historical context.[73]

Max and Moritz

[edit]In German, Eine Bubengeschichte in sieben Streichen, Max and Moritz is a series of seven illustrated stories concerning the mischievous antics of two boys, who are eventually ground up and fed to ducks.

Saint Antonius of Padua and Helen Who Couldn't Help It

[edit]

In Saint Antonius of Padua (Der Heilige Antonius von Padua) Busch challenges Catholic belief. It was released by the publisher Moritz Schauenburg at the time Pope Pius IX proclaimed the dogma of papal infallibility that was harshly criticized by Protestants.[74] The publisher's works were heavily scrutinized or censored,[75] and the state's attorney in Offenburg charged Schauenberg with "vilification of religion and offending public decency through indecent writings" – a decision which affected Busch.[76] Scenes of Antonius accompanied by a pig being admitted to heaven, and the devil being shown as a half-naked ballet dancer seducing Antonius, were deemed controversial. The district court of Düsseldorf subsequently banned Saint Antonius. Schauenburg was acquitted on 27 March 1871 in Offenburg, but in Austria distribution of the satire was prohibited until 1902.[77] Schauenburg refused to publish further Busch satires to avoid future accusations.[78]

Busch's following work, Helen Who Couldn't Help It (Die fromme Helene), was published by Otto Friedrich Bassermann, a friend whom Busch met in Munich. Helen Who Couldn't Help It, which was soon translated into other European languages, satirizes religious hypocrisy and dubious morality:[79][80]

|

Ein guter Mensch gibt gerne acht, |

A saintly person likes to labor

|

Many details from Helen Who Couldn't Help It criticize the way of life of the Kesslers. Johanna Kessler was married to a much older man and entrusted her children to governesses and tutors, while she played an active role in the social life of Frankfurt.[81]

|

Schweigen will ich vom Theater |

Then again, the pen would rather

|

The character of Mr. Schmock – the name based on the Yiddish insult "schmuck" – shows similarities with Johanna Kessler's husband, who was uninterested in art and culture.[82]

In the second part of Helen Who Couldn't Help It Busch attacks Catholic pilgrimages. The childless Helen goes on a pilgrimage, accompanied by her cousin and Catholic priest Franz. The pilgrimage is successful, as later Helen gives birth to twins, who resemble Helen and Franz. Franz is later killed by a jealous valet, Jean, for his interest in female kitchen staff. The now widowed Helen is left with only a rosary, prayer book, and alcohol. Drunk, she falls into a burning oil lamp. Finally, Nolte coins a moral phrase, echoing the philosophy of Schopenhauer:[83][84]

|

Das Gute — dieser Satz steht fest — |

The good (I am convinced, for one)

|

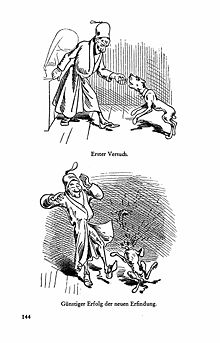

Pater Filucius (Father Filucius) is the only illustrated satire of this period suggested by the publisher. Also aimed at anti-Catholic taste and buyers, it criticizes the Jesuit Order. Kraus felt it was the weakest of all three anti-clerical works.[85] Some satires refer to contemporary events, such as Monsieur Jacques à Paris during the Siege of 1870 (Monsieur Jacques à Paris während der Belagerung von 1870). Busch biographer Michaela Diers declares the story "tasteless work, drawing on anti-French emotions and mocking the misery of French people in Paris, which is occupied by Prussian troops".[86] It depicts an increasingly desperate French citizen who at first eats a mouse during the German siege, then amputates his dog's tail to cook it, and finally invents an explosion pill which kills his dog and two fellow citizens.[87] Weissweiler believes that Busch wrote with irony.[53] In Eginhard and Emma (1864), a fictional family story that takes place in the Charlemagne era, he criticizes the Holy Roman Empire and calls for a German empire in its place; in The Birthday or the Particularists (Der Geburtstag oder die Partikularisten) he satirizes the anti-Prussian sentiments of his Hanover countrymen.[88]

Critique of the Heart

[edit]

Busch did not write illustrated tales for a while, but focused on the literary Kritik des Herzens (Critique of the Heart), wanting to appear more serious to his readers. Contemporary reception for the collection of 81 poems was mainly poor; it was criticized for its focus on marriage and sexuality. His long-time friend Paul Lindau called it "very serious, heartfelt, charming poems".[89] Dutch writer Marie Anderson was one of few people who enjoyed his Kritik des Herzens, and she even planned to publish it in a Dutch newspaper.[90]

Adventures of a Bachelor

[edit]Notwithstanding the hiatus after moving from Frankfurt, the 1870s were one of Busch's most productive decades. In 1874 he produced the short illustrated tale, Diddle-Boom! (Dideldum!).

Following in 1875, was the Knopp Trilogy, about the life of Tobias Knopp: Adventures of a Bachelor (Abenteuer eines Junggesellen), Mr. and Mrs. Knopp (Herr und Frau Knopp) (1876), and "Julie" (Julchen) (1877). The antagonists of the trilogy are not pairs of nuisances as with Max and Moritz or Jack Crook, Bird of Evil (Hans Huckebein, der Unglücksrabe).[91] Without pathos, Busch makes Knopp become aware of his mortality:[92]

|

Rosen, Tanten, Basen, Nelken |

April, cousins, maidens, May

|

In the first part of the trilogy, Knopp is depressed and will look for a wife. He visits his old friends and their wives, whom he finds in unenviable relationships. Still not convinced that the life of a bachelor is one for him, he returns home, and without further ado proposes to his housekeeper. The following marriage proposal is, according to Busch biographer Joseph Kraus, one of the shortest in the history of German literature:[93][94]

|

"Mädchen", spricht er, "sag mir ob..." |

"Wench," he stammers, "if I were..."

|

According to Wessling, Busch became skeptical of marriage after writing the story.[95] To Marie Anderson he wrote: "I will never marry(...) I am already in good hands with my sister".[96]

Last works

[edit]Among Busch's last works were the stories, Clement Dove, the Poet Thwarted (Balduin Bählamm, der verhinderte Dichter) (1883) and Painter Squirtle (Maler Klecksel) (1884), both of which focus on artistic failure, and indirectly his own failure.[97] Both stories begin with a preface, which, for biographer Joseph Kraus, were bravura pieces of "Komische Lyrik" — German comic poetry.[98] Clement Dove ridicules the bourgeois amateur poet circle of Munich, "The Crocodiles" (Die Krokodile), and their prominent members Emanuel Geibel, Paul von Heyse, and Adolf Wilbrandt. Painter Squirtle criticizes the bourgeois art connoisseur who believes the worth of art is gauged by its price.[99]

|

Mit scharfen Blick nach Kennerweise |

For just a minute comment lags,

|

The prose play Edwards Dream (Eduards Traum) was released in 1891, composed of several small grouped episodes, rather than one linear storyline. The work received mixed reception. Joseph Kraus felt it was the peak of the life works by Busch,[100] his nephews called it a masterwork of world literature, and the publisher of a critical collective edition spoke of a narrative style that is not found in contemporary literature.[101] Eva Weissweiler saw in the play Busch's attempt to prove himself in the novella genre, believing that everything that angered or insulted him, and his accompanying emotional depths, are apparent in the story.[102] The 1895 story The Butterfly (Der Schmetterling) parodies themes and motifs and ridicules the religious optimism of a German romanticism that contradicted Busch's realistic anthropology influenced by Schopenhauer and Charles Darwin.[103] Its prose is more stringent in narrative style when compared to Edwards Dream. Both were not popular amongst readers, because of their unfamiliar style.[104]

Painting

[edit]

Busch felt his painting skills could not compete with those of the Dutch masters.[34] He regarded few of his paintings as finished, often stacking them one on top of the other in damp corners of his studio, where they stuck together. If the pile of paintings became too high, he burnt some in his garden.[105] Since only a few remaining paintings are dated, categorizing them is difficult.[34] His doubts regarding his skills are expressed in his choice of materials. His ground was usually chosen carelessly. Sometimes he used uneven cardboard or poorly-prepared spruce-wood boards.[105] One exception is a portrait of Johanna Kessler, on a canvas support measuring 63 centimetres (25 in) by 53 centimetres (21 in), one of his largest paintings.[105] Most of his works, even landscapes, are small.[105] As Busch used poor grounds and colours, most are heavily darkened and have an almost monochrome effect.

Many pictures depict the countryside at Wiedensahl and Lüthorst. They include pollarded willows, cottages in cornfields, cowherds, autumn landscapes, and meadows with streams.[106] A particular feature is the use of red jackets, found in about 280 of 1000 Busch paintings and drawings. The muted or bright red coats are worn usually by a small figure, depicted from behind.[107] The paintings generally represent typical villages. Portraits of the Kesslers, and a series of other portraits depicting Lina Weissenborn in the mid-1870s, are exceptions. A painting of a 10-year-old girl from a Jewish family at Lüthorst portrays her as serious, and having dark, oriental features.[108]

The influence of Dutch painters is clearly visible in Busch's work. "Hals diluted and shortened(...) but still Halsian", wrote Paul Klee after visiting a Busch memorial exhibition in 1908.[109] A strong influence on Busch was Adriaen Brouwer, whose themes were farming and inn life, rustic dances, card players, smokers, drunkards, and rowdies. He dismissed the techniques of Impressionism with its strong preoccupation with the effect of light, and used new colours, such as Aniline Yellow, and photographs, as an aid. The landscapes from the mid-1880s show the same broad brushstrokes as seen in the paintings of the young Franz von Lenbach.[110] Busch refused to exhibit work even though he was befriended by many artists of the Munich School, which would have allowed him to do so;[111] it was not until near the end of his life that he presented his paintings to the public.[33]

Themes, technique, and style

[edit]

Busch biographer Joseph Kraus divided his work into three periods. He points out, however, that this classification is a simplification, as some works by their nature may be of a later or earlier period.[112] All three periods show Busch's obsession with German middle class life.[113] His peasants are devoid of sensitivity and village life is marked by a vivid lack of sentiment.[114]

From 1858 to 1865 Busch chiefly worked for the Fliegenden Blätter and the Münchener Bilderbogen.

The period from 1866 to 1884 is characterized by his major illustrated stories, such as Helen Who Couldn't Help It. These stories are different in theme from works of his earlier period. The life of his characters start well, but disintegrate, as in Painter Squirtle (Maler Klecksel); someone sensitive who becomes a pedant. Others concern recalcitrant children or animals, or make the great or significant foolish and ridiculous.[115] The early stories follow the pattern of children's books of orthodox education, such as those by Heinrich Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter, that aim to teach the devastating consequences of bad behaviour.[116] Busch did not assign value to his work, as he once explained to Heinrich Richter: "I look at my things for what they are, as Nuremberg trinkets [toys], as Schnurr Pfeiferen [worthless and useless things] whose value is to be found not in its artistic content, but in public demand (...)".[117]

From 1885 until his death in 1908 his work was dominated by prose and poems. The 1895 prose text Der Schmetterling contains autobiographical accounts.[118] Peter's enchantment by the witch Lucinde, of whom he regards himself a slave, is possibly in reference to Johanna Kessler. Peter, like Busch, returns to his birthplace. It is similar in style to the romantic travel story that Ludwig Tieck established with his 1798 Franz Sternbalds Wanderungen. Busch plays with its traditional forms, motifs, pictures, literary topics, and form of narration.[119]

Technique

[edit]Publisher Kaspar Braun, who commissioned Busch's first illustrations, had established the first workshop in Germany to use wood engraving. This letterpress printing technique was developed by English graphic artist Thomas Bewick near the end of the eighteenth century and became the most widely used reproduction system for illustrations over the years. Busch insisted on first making the drawings, afterward writing the verse. Surviving preparatory drawings show line notes, ideas, and movement, and physiognomy studies.[120]

Then the draft was transferred by pencil on white-primed panels of hardwood end grain. Not only was it hard work, but the quality of the printing block was crucial.[121] Everything left white on the block, around Busch's drawn lines, was cut from the plate by skilled engravers. Wood engraving allows a finer differentiation than woodcut and the potential tonal values are of almost the quality of intaglio printing, such as copper engraving. Sometimes the result was not satisfactory, leading Busch to rework or reproduce plates.[122] The wood engraving technique did not allow for fine lines, which is why Busch's drawing, especially in his illustrated tales up to the mid-1870s, are boldly drawn, giving his work its particular characteristic.[123]

From the mid-1870s Busch's illustrations were printed using zincography. With this technique there was no longer any danger that a wood engraver could change the character of his drawings. The originals were photographed and transferred onto a photosensitive zinc plate. This process allowed for the application of a clear, free pen-drawn ink line, and was a much faster printing method. Busch's use of zincography began with Mr. and Mrs. Knopp.[124]

Language

[edit]The effect of Busch's illustrations is enhanced by his forthright verse, with taunts, derision, ironic twists, exaggeration, ambiguity, and startling rhymes.[125] His language had an influence on the humorous poetry of Erich Kästner, Kurt Tucholsky, Joachim Ringelnatz, and Christian Morgenstern.[126] The contrast in his later work between comic illustration and its seemingly serious accompanying text – already demonstrated in his earlier Max and Moritz – is shown in Widow Bolte's mawkish dignity, which is disproportionate to the loss of her chickens:[127]

|

Fließet aus dem Aug', ihr Tränen! |

Flow, my tears, then, scoring, burning,

|

Many of Brusch's couplets, part of contemporary common usage, give the impression of weighty wisdom, but in his hands become only apparent truths, hypocrisy, or platitudes. His use of onomatopoeia is a characteristic of his work: "Allez-oop-da" — Max and Moritz steal fried chickens with a fishing rod down a chimney — "reeker-rawker"; "at the plank from bank to bank"; "rickle-rackle", "hear the millstones grind and crackle"; and "tinkly-clinket" as Eric the cat rips a chandelier from a ceiling in Helen Who Couldn't Help It. Busch uses names he gives characters to describe their personality. "Studiosus Döppe" (Young Bumbel) has little mental ability; "Sauerbrots" (Sourdough) would not be of a cheerful disposition; and "Förster Knarrtje" (Forester Knarrtje) could hardly be a socialite.[128]

Many of his picture stories use verses with trochee structure:[129]

Master Lampel's gentle powers

Failed with rascals such as ours

The overweighting of the stressed syllables strengthens the humour of the lines. Busch also uses dactyls, where one accented syllable is followed by two unaccented syllables, as in his Plisch und Plum, where they underline the pedantic and solemn words with which teacher Bokelmann educates his pupils. They create tension in the Sourdough chapter from Adventures of a Bachelor, through the alternation of trochees and dactyls.[130] Busch often synchronizes format and content in his poems, as in Fips the Monkey, where he uses the epic hexameter in a speech about wisdom.[131]

In both his illustrations and poems Busch uses familiar fables, occasionally appropriating their morality and stories, spinning them to illustrate a very different and comic "truth",[132] and bringing to bear his pessimistic view of the world and human condition. While traditional fables follow the typical philosophy of differentiating between good and evil behaviour, Busch combines both.[133]

Canings and other cruelties

[edit]

It is not unusual to see thrashing, tormenting, and caning in Busch's works. Sharp pencils pierced through models, housewives fall onto kitchen knives, thieves are spiked by umbrellas, tailors cut their tormentors with scissors, rascals are ground in corn mills, drunkards burn, and cats, dogs, and monkeys defecate while being tormented. Frequently Busch has been called a sadist by educators and psychologists.[134] Tails that are burnt, pulled off, trapped, stretched, or eaten is seen by Weissweiler as not aggression against animals, but a phallic allusion to Busch's undeveloped sexual life.[82] Such graphic text and imagery in cartoon form was not unusual at the time, and publishers, the public, or censors found it not particularly noteworthy.[30] Topics and motifs for his early work were derived from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century popular literature, the gruesome endings of which he often softened.[135]

Caning, a common aspect of nineteenth-century teaching, is prevalent in many of his works, for example Meister Druff in Adventures of a Bachelor and Lehrer Bokelmann in Plish and Plum, where it is shown as an almost sexual pleasure in applying punishment.[136] Beatings and humiliation are found in his later work too; biographer Gudrun Schury described this as Busch's life-motif.[137]

In the estate of Busch there is the note, "Durch die Kinderjahre hindurchgeprügelt" (Beaten through the childhood years),[138] however there is no evidence that Busch was referring to himself.[139] He couldn't recall any beating from his father. His uncle Kleine beat him once, not with the conventional rattan stick, but symbolically with dried dahlia stalks, this for stuffing cow hairs into a village idiot's pipe.[140] Weissweiler observes that Busch probably saw canings at his village school, where he went for three years, and quite possibly he also received this punishment.[141] In Abenteuer eines Junggesellen Busch illustrates a form of nonviolent progressive education that fails in one scene, and caning in the following scene; the canings that ensued indicate Busch's pessimistic picture of life, which has its roots in the Protestant ethic of the nineteenth century,[142] in which he believed that humans are inherently evil and will never master their vices. Civilisation is the aim of education, but it can only mask human instincts superficially.[143] Gentleness only leads to a continuation of human misdeeds, therefore punishment is required, even if one retains an unrepentant character, becomes a trained puppet, or in extreme cases, dies.[144]

Antisemitism

[edit]

The Panic of 1873 led to growing criticism of high finance and the spread of radical Antisemitism, which in the 1880s became a broad undercurrent.[145] These criticisms saw a separation of capital into what was construed as "raffendes" (speculative capital), and what constituted "constructive" creative production capital. The "good", "native", and "German" manufacturer was praised by Antisemitic agitators, such as Theodor Fritsch, who opposed what he saw as "'rapacious' 'greedy', 'blood-sucking', 'Jewish' financial capitalism in the form of 'plutocrats' and 'usurers'".[146] Busch was thought to have embraced those stereotypes. Two passages are often underlined, one in Helen Who Couldn't Help It:

|

Und der Jud mit krummer Ferse, |

And the Hebrew, sly and craven,

|

Robert Gernhardt defended Busch by stating that Jews are satirized only in three passages, of which the oldest is an illustration of a text by another author, published in 1860. He stated that Busch's Jewish figures are merely stereotypical, one of a number of stereotypes, such as the "limited Bavarian farmer" and the "Prussian tourist".[147] Joseph Kraus shares the same view, and uses a couplet from Eight Sheets in the Wind (Die Haarbeutel),[148] in which profit-seeking people are:

|

Vornehmlich Juden, Weiber, Christen, |

Most often wenches, Christians, Jews,

|

Although Gernhardt felt that Jews for Busch were alien, the Jewish conductor Hermann Levi befriended him, suggesting that Busch had a slight bias towards Jews.[149]

Biographies

[edit]The first biography on Busch, Über Wilhelm Busch und seine Bedeutung (About Wilhelm Busch and His Importance), was released in 1886. The painter Eduard Daelen, also a writer, echoed Busch's anti-Catholic bias, putting him on equal footing with Leonardo da Vinci, Peter Paul Rubens, and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, and uncritically quoting correspondences. Even Busch and his friends were embarrassed.[150] Literary scholar Friedrich Theodor Vischer attacked Daelen's biography and called him the "envious eunuch of the desiccated Philistine".[151] After reading this biography Johannes Proelß posted an essay in the Frankfurter Zeitung, which contained many biographical falsehoods – as a response to this, Busch wrote two articles in the same newspaper. Published in October and December 1886, the autobiographical essay Regarding Myself (Was mich betrifft) includes basic facts, and some description of his troubles;[152] analysts see within the essay a deep identity crisis.[153] Busch revised his autobiography over the following years. The last such essay was published under the title, From Me About Me (Von mir über mich), which includes fewer biographical details and less reflection on bitterness and amusement than Regarding Myself.[154]

Legacy

[edit]

Busch celebrated his 70th birthday at his nephew's house in Hattorf am Harz. More than 1,000 congratulatory messages were sent to Mechtshausen from around the world. Wilhelm II praised the poet and artist, whose "exquisite works are full of genuine humour and are everlasting for the German people".[155] The Austrian Alldeutsche Vereinigung (Pan-German Association) repealed the ban on Der heilige Antonius von Padua.[156] Verlag Braun & Schneider, who owned the rights of Max and Moritz, gave Busch 20,000 ℛ︁ℳ︁ (around €200,000 or $270,000), which was donated to two hospitals in Hanover.[156]

Since then, on the anniversary dates of his birth and death, he has been celebrated frequently. During the 175th anniversary in 2007, there were numerous re-publications of Busch works. Deutsche Post issued stamps depicting the Busch character Hans Huckebein – itself the inspiration for the nickname of the never-built Focke-Wulf Ta 183 German jet fighter design of 1945 – and the German Republic minted a 10 Euro silver coin faced with his portrait.[157] Hanover declared 2007 the "Wilhelm Busch Year", with images featuring Busch works erected within the city centre.[158]

The Wilhelm Busch Prize is awarded annually for satirical and humorous poetry. The Wilhelm Busch Society, active since 1930, aims to "(...) collect, scientifically revise, and promote Wilhelm Busch's works with the public". It supports the development of caricature and satirical artwork as a recognized branch of the visual arts.[159] It is an advocate of the Wilhelm Busch Museum.[160] Memorials are located in places he lived, including Wiedensahl, Ebergötzen, Lüthorst, Mechtshausen, and Hattorf am Harz.[161]

On 15 April 2012, Google celebrated Wilhelm Busch’s 180th Birthday with a doodle.[162]

Influence on comics

[edit]Andreas C. Knigge described Busch as the "first virtuoso" of illustrated stories.[163] From the second half of the twentieth century he was considered the "Forefather of Comics".[164] His early illustrations differ from those of the colleagues of Kaspar Braun. They show an increasing focus on protagonists, are less detailed in drawing and atmosphere, and develop from a dramatic understanding of the whole story.[165] All Busch's illustrated tales have a plot that firstly describes the circumstance, then a resulting conflict, then solution.[166] Plots are developed through consecutive scenes, similar to film storyboards. Busch conveys an impression of movement and action, at times strengthened through a change of perspective.[167] According to Gert Ueding, his depiction of movement is unique.[168]

One of Busch's notable stories is Der Virtuos (1865), which describes the life of a pianist who plays privately for an excited listener. Satirizing the self-publicizing artist's attitude and his overblown adoration, it varies from Busch's other stories as each scene does not contain prose, but is defined with music terminology, such as "Introduzione", "Maestoso", and "Fortissimo vivacissimo". As the scenes increase in tempo, each part of his body and lappet run around. The penultimate scene again depicts the pianist's movements, with score sheets floating above the grand piano on which musical notes are dancing.[169][170] Over the years graphic artists have been fascinated by Der Virtuos. August Macke, in a letter to gallery owner Herwarth Walden, described Busch as the first Futurist, stating how well he captured time and movement.[171] Similar pioneering scenes are in Bilder zur Jobsiade (1872). Job fails to answer rather easy questions set by twelve clergy, who shake their heads in synchronicity. Each scene is a movement study that presages Eadweard Muybridge's photography. Muybridge began his work in 1872, not released until 1893.[172]

"Moritzian" influence

[edit]

Busch's greatest success, both within Germany and internationally, was with Max and Moritz:[173] Up to the time of his death it was translated into English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish, and Walloonian.[174] Several countries banned the story – about 1929 the Styrian school board prohibited sales of Max and Moritz to teens under eighteen.[175] By 1997 more than 281 dialect and language translations had been produced.[176]

Some early "Moritzian" comic strips were heavily influenced by Busch in plot and narrative style. Tootle and Bootle (1896), borrowed so much content from Max and Moritz that it was described as a pirate edition.[177] The true "Moritzian" recreation is The Katzenjammer Kids by German artist Rudolph Dirks, published in the New York Journal from 1897. It was published though William Randolph Hearst's suggestion that a pair of siblings following the pattern of "Max and Moritz" should be created.[177] The Katzenjammer Kids is regarded as one of the oldest, continuous comic strips.[178]

German "Moritzian"-inspired stories include Lies und Lene; die Schwestern von Max und Moritz (Hulda Levetzow, F. Maddalena, 1896), Schlumperfritz und Schlamperfranz (1922), Sigismund und Waldemar, des Max und Moritz Zwillingspaar (Walther Günther, 1932), and Mac und Mufti (Thomas Ahlers, Volker Dehs, 1987).[179] These are shaped by observations of the First and Second World Wars, while the original is a moral story.[180] In 1958 the Christian Democratic Union used the Max and Moritz characters for a campaign in North Rhine-Westphalia, the same year that the East German satirical magazine Eulenspiegel used them to caricature black labour. In 1969 Max and Moritz "participated" in late 1960s student activism.[181]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b ""Dieses war der erste Streich, Doch der zweite folgt sogleich" - Wilhelm Busch" (in German). Archion. 14 April 2022.

- ^ a b Galway, Carol (2000). "Wann hatte Wilhelm Busch wirklich Geburtstag?" [When was Wilhelm Busch's birthday, really?]. Germanic Notes and Reviews (in German). 31 (1): 14–18. ISSN 0016-8882.

- ^ Töpper, Stephan (22 December 2007). "Urvater des Comics" [Forefather of Comics]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Kraus, p. 9

- ^ Pape, p. 14

- ^ Schury, p. 17

- ^ Schury, p. 16

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 14

- ^ Wessling, p. 22

- ^ Wessling, p. 22, 24

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 20

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 27

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 26

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 25–27

- ^ Schury, pp. 32–33

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 29

- ^ Diers, p. 16

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 33–34

- ^ Weisweiler, p. 32

- ^ Diers, p. 15

- ^ Schury, p. 41

- ^ Schury, p. 36

- ^ Kraus, p. 10

- ^ Wessling, pp. 30–32

- ^ Ueding, p. 36

- ^ Kraus, p. 165

- ^ Kraus, p. 24

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 43–44

- ^ Diers, p. 21

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 51

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 56

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 64

- ^ a b Schury, p. 49

- ^ a b c Kraus, p. 30

- ^ Busch, Bohne, Meskemper, Haberland, p. 6

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 75

- ^ Kraus, p. 32

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 80

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 84

- ^ Diers, p. 31

- ^ Schury, p. 72

- ^ Diers, p. 34

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 95

- ^ Diers, p. 75

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 102–9

- ^ a b Diers, p. 120

- ^ Kraus, p. 147

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 265

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 118

- ^ a b Diers, pp. 45–46

- ^ Diers, p. 63

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 132–133

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 138

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 155

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 156

- ^ Kraus, p. 55

- ^ Diers, pp. 75–76

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 159

- ^ Wessing, p. 85

- ^ a b Weissweiler, pp. 232–234

- ^ Kraus, p. 58

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 237

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 252–253

- ^ Diers, p. 119

- ^ a b Weissweiler, pp. 270–271

- ^ Wesslng, p. 161

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 332.

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 334

- ^ Kraus, p. 153

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 344

- ^ Kraus, p. 61

- ^ Diers, p. 99

- ^ Kraus, p. 68

- ^ Wessing, pp. 92–93

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 168

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 166–167

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 169–172

- ^ Wessling, p. 100

- ^ Wessling, p. 106

- ^ Arndt, p. 56

- ^ Arndt, p. 42

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 194

- ^ Kraus, p. 64

- ^ Arndt, p. 64

- ^ Kraus, p. 66

- ^ Diers, pp. 90–91

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 177

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 179

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 229

- ^ Kraus, p. 57

- ^ Kraus, p. 94

- ^ Arndt, pp. 66–7

- ^ Kraus, p. 97

- ^ Arndt, p. 82

- ^ Wessling, p. 155

- ^ zitiert nach Wessling, p. 155

- ^ Diers, p. 147

- ^ Kraus, p. 101

- ^ Arndt, p. 160

- ^ Kraus, p. 130

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 316–317

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 320–322.

- ^ Clemens Heydenreich: "... und damit gut!" Wilhelm Buschs Märchen "Der Schmetterling" als Trümmerfeld der "Taugenichts"-Romantik. (In German) In: Aurora. Jahrbuch der Eichendorff-Gesellschaft, 68/69 (2010), pp. 67–78

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 330–331

- ^ a b c d Weissweiler, pp. 163–164

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 139

- ^ Schury, pp. 52–53

- ^ Weissweiler, S. 215 und S. 216

- ^ Ueding, p. 369

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 310

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 164

- ^ Kraus, p. 46

- ^ Ueding, pp. 296–297

- ^ Ueding, pp. 301–302

- ^ Ueding, p. 46

- ^ Ueding, pp. 71–72

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 120

- ^ Pietzcker, Frank: Symbol und Wirklichkeit im Werk Wilhelm Buschs – Die versteckten Aussagen seiner Bildergeschichten., Europäische Hochschulschriften, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-39313-X, pp. 71, 104

- ^ Ueding, p. 221

- ^ Schury, p. 87

- ^ Schury, pp. 89–90

- ^ Schury, p. 91

- ^ Diers, pp. 41–42

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 254

- ^ Kraus, p. 126

- ^ Wessling, pp. 120–121

- ^ Kraus, p. 47

- ^ Diers, p. 118

- ^ Pietzcker, p. 26

- ^ Pietzcker, pp. 28–30

- ^ Pietzcker, p. 30

- ^ Ueding, pp. 103, 105

- ^ Ueding, pp. 106–107

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 94

- ^ Pietzcker, pp. 15–16

- ^ Mihr, pp. 76–79

- ^ Schury, p. 27

- ^ Mihr, p. 71

- ^ Schury, p. 23

- ^ Kraus, p. 15

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 22

- ^ Mihr, pp. 27–40, 61–70

- ^ Pietzcker, p. 67

- ^ Schury, pp. 29–30

- ^ Ullrich, Volker: Die nervöse Großmacht: Aufstieg und Untergang des deutschen Kaiserreichs 1871–1918, Fischer Taschenbuch 17240, Frankfurt on the Main, 2006, ISBN 978-3-596-11694-2, p. 383

- ^ Piefel, Matthias: Antisemitismus und völkische Bewegung im Königreich Sachsen 1879–1914, V&R unipress Göttingen, 2004, ISBN 3-89971-187-4

- ^ Gernhardt, Robert. "Schöner ist doch unsereiner" (in German). Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ^ Kraus, pp. 88–89

- ^ Kraus, p. 90

- ^ Kraus, p. 71

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 308–309

- ^ Krause, p. 77

- ^ Wessling, p. 181

- ^ Kraus, p. 78

- ^ Weissweiler, p. 340

- ^ a b Kraus, p. 156

- ^ "Wilhelm Busch wird mit 10-Euro-Silbergedenkmünze geehrt" (in German), Pressedienst Numismatik, 7 June 2007

- ^ Lammert, Andrea (15 April 2007). "Zuhause bei Max und Moritz" [At Home with Max and Moritz]. Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ "Home Page" (in German). Wilhelm Busch – Deutsches Museum für Karikatur & Zeichenkunst. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Homepage of the Deutsches Museum für Karikatur und Zeichenkunst (in German). Retrieved on 14 January 2013

- ^ "Gedenkstätten" [Memorials] (in German). Deutsches Museum für Karikatur und Zeichenkunst. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ Desk, OV Digital (14 April 2023). "14 April: Remembering Wilhelm Busch on Birthday". Observer Voice. Retrieved 14 April 2023.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Knigge, Andreas C.: Comics – Vom Massenblatt ins multimediale Abenteuer, p. 14. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, 1996.

- ^ Töpper, Stephan (22 December 2007). "Urvater des Comics" [Forefather of Comics]. Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ^ Schury, p. 80

- ^ Ruby, Daniel: Schema und Variation — Untersuchungen zum Bildergeschichtenwerk Wilhelm Buschs. Europäische Hochschulschriften, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-631-49725-3, p. 26

- ^ Ueding, p. 193.

- ^ Ueding, p. 196

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 142–143

- ^ Schury, p. 81

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 143–144

- ^ Weissweiler, pp. 204–205

- ^ Wessling, p. 73

- ^ Schury, p. 99

- ^ Wessling, p. 76

- ^ Diers, p. 64

- ^ a b Weissweiler, p. 331

- ^ Claire Suddath (17 May 2010). "Top 10 Long-Running Comic Strips / The Katzenjammer Kids". Time magazine. Archived from the original on 20 May 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Diers, pp. 65–67

- ^ Ueding, p. 80

- ^ Diers, p. 67

Works cited

[edit]- Arndt, Walter (1982). The Genius of Wilhelm Busch. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03897-5.

- Busch, Wilhelm (1982). Bohne, Friedrich; Meskemper, Paul; Haberland, Ingrid (eds.). Sämtliche Briefe. Kommentierte Ausgabe in 2 Bänden / Wilhelm Busch (in German). Hannover: Wilhelm Busch Association and Schlüter. ISBN 3-87706-188-5.

- Diers, Michaela (2008). Wilhelm Busch, Leben und Werk (in German). dtv. ISBN 978-3-423-34452-4.

- Kraus, Joseph (2007). Wilhelm Busch (in German). Reinbek near Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-499-50163-0.

- Mihr, Ulrich (1983). Wilhelm Busch: Der Protestant, der trotzdem lacht. Philosophischer Protestantismus als Grundlage des literarischen Werks (in German). Tübingen: Narr. ISBN 3-87808-920-1.

- Pape, Walter (1977). Wilhelm Busch (in German). Metzler. ISBN 978-3-476-10163-1.

- Pietzcker, Frank (2002). Symbol und Wirklichkeit im Werk Wilhelm Buschs – Die versteckten Aussagen seiner Bildergeschichten (in German). Frankfurt on the Main: Europäische Hochschulschriften. ISBN 3-631-39313-X.

- Schury, Gudrun (2007). Ich wollt, ich wär ein Eskimo. Das Leben des Wilhelm Busch. Biographie (in German). Berlin: Aufbau-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-351-02653-0.

- Ueding, Gert (2007). Wilhelm Busch. Das 19. Jahrhundert en miniature (in German). Frankfurt on the Main / Leipzig: Insel. ISBN 978-3-458-17381-6.

- Weissweiler, Eva (2007). Wilhelm Busch. Der lachende Pessimist. Eine Biographie (in German). Cologne: Kiepenheuer & Witsch. ISBN 978-3-462-03930-6.

External links

[edit]- Biography and works (in German)

- Collection of known works (Projekt Gutenberg-DE)

- Spiegel Online's version in German of the Busch work "Hans Huckebein", origin for the Focke-Wulf Ta 183 jet fighter's name

- Works by Wilhelm Busch at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Wilhelm Busch (German) at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Wilhelm Busch at the Internet Archive

- Works by Wilhelm Busch at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- www.zeno.org Wilhelm Busch collection at Zeno.org (in German)

- Paintings by Wilhelm Busch

- 1832 births

- 1908 deaths

- People from Schaumburg

- People from the Kingdom of Hanover

- German Lutherans

- German illustrators

- German children's writers

- German children's book illustrators

- 19th-century German painters

- 19th-century German male artists

- German male painters

- 20th-century German painters

- 20th-century German male artists

- German caricaturists

- German comics writers

- German comics artists

- German satirists

- German satirical novelists

- Grotesque

- Writers from Lower Saxony

- German male essayists

- German male poets

- 19th-century German poets

- German-language poets

- 19th-century German male writers

- 19th-century German essayists

- University of Hanover alumni

- 19th-century Lutherans