Hammer mill

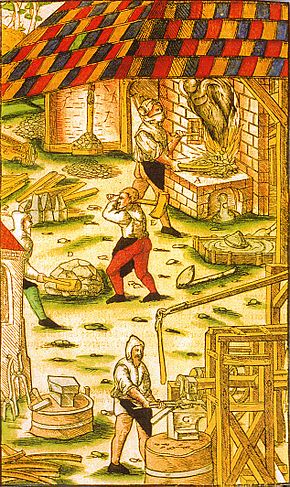

A hammer mill, hammer forge or hammer works was a workshop in the pre-industrial era that was typically used to manufacture semi-finished, wrought iron products or, sometimes, finished agricultural or mining tools, or military weapons. The feature that gave its name to these workshops was the water-driven trip hammer, or set of hammers, used in the process. The shaft, or 'helve', of the hammer was pivoted in the middle and the hammer head was lifted by the action of cams set on a rotating camshaft that periodically depressed the end of the shaft. As it rose and fell, the head of the hammer described an arc. The face of the hammer was made of iron for durability.[2]

Hammer mills

[edit]

These mills, which were original driven by water wheels, but later also by steam power, became increasingly common as tools became heavier over time and therefore more difficult to manufacture by hand.

The hammer mills smelted iron ore using charcoal in so-called bloomeries (Georgius Agricola 1556, Rennherden, Rennfeuer or Rennofen: from Rinnen = "rivulets" of slag or Zrennherd from Zerrinnen = "to melt away"). In these smelting ovens, which were equipped with bellows also driven by water power, the ore was melted into a glowing clump of soft, raw iron, fluid slag and charcoal remnants. The iron was not fluid as it would be in a modern blast furnace, but remained a doughy, porous lump mainly due to the presence of liquid slag. These lumps of sponge iron, known historically as "blooms" were initially compacted by hand using a sledgehammer. After that they were forged several times, usually with the trip hammer or with sledgehammers until all the slag and charcoal had been removed. For that, the iron was heated in another forge oven or smith's hearth. The iron could then be directly used as soft iron. A further improvement process, such as fining as used in blast furnace operations, was not needed.

The resulting coarse bar iron was then further worked externally e.g. in special, small hammer works (Zainhammer) into thin iron rods, (e.g. thick wire), so-called rod iron (Zaineisen), which was needed by nailsmiths to produce nails.

Further processing into so-called refined iron or into "elastic" steel for e.g. for sword blades, was carried out by specialised refined iron hammer forges or by blacksmiths on site.

Distribution

[edit]Geographically, hammer mills were dependent on the availability of water power. At the same time, there had to be forests nearby to produce the large quantities of charcoal needed. In addition, there had to be deposits of iron ore in the vicinity in order to ensure that there was only a short distance to transport the iron-containing ores to the smelteries. Finally, agricultural land was needed in order to feed the many craftsmen involved.

Germany

[edit]Hammer mills were widespread from the late Middle Ages in the following regions:

- Bergisches Land (with more than one hundred sites[3])

- Upper Palatinate, especially in the area of the towns of Amberg and Sulzbach

- Thuringian Forest: Lauterhammer and Niederhammer in Suhl by 1363, Tobiashammer in Ohrdruf (later also Kupferhammer and copper hammer mill)

- Fichtel Mountains

- Ore Mountains: 1352 Hammer in Pleil, c. 1380 Hammer Erla, Frohnauer Hammer

- Harz Mountains

- Siegerland on the Sieg river (today around Siegen)

- Sauerland around Hagen

- Lahn-Dill Region and on the upper Eder river

In these regions there were iron ore deposits, which could be extracted with the means available at the time. There was a higher density in the Wupperviereck, where there were several hundred sites.

The Upper Palatinate was one of the European centres of iron smelting and its many hammer mills led to its nickname as the "Ruhrgebiet of the Middle Ages". Placenames with the suffix -hammer are very common in this region. The home of the lord in charge of a hammer mill was rather grandly known as a "hammer castle" or "hammer palace" (Hammerschloss). This usually inconspicuous schloss, which acted as the family seat of the "hammer lord", was generally located in the immediate vicinity of the mill. Important hammer castles may be seen along the Bavarian Iron Route, for example in Theuern, Dietldorf and Schmidmühlen[4]

Austria

[edit]In Austria the hammer mills were mainly found in the Iron Roots (Eisenwurzen) along the Austrian Iron Route around the tripoint of the states of Lower Austria, Styria and Upper Austria (e. g. Ybbsitz) and in the Upper Styrian valleys of the Mur and Mürz and their side valleys. The seats of the hammer lords ("black counts") were known as Hammerherrenhäuser ("hammer lord manors").

France

[edit]Steelworkers in Thiers, France used hammer mills, powered by the Durolle River in the Vallée des Rouets, for the production of knives and other cutlery until the middle of the 19th century.[5]

England

[edit]Hammer mills were not widespread in England, but there are examples such as the one at Abinger Hammer in Surrey from which the village derived its name.[6]

Products

[edit]Typical produces of the hammer mills were:

- bar iron,

- rails,

- blackplate,

- tinplate and

- wire.

These products were usually produced as semi-finished articles, but were sometimes also further forged into finished products such as sickles, scythes, shovels, weapons or miners' tools.

Well known hammer mills

[edit]

Most of the mills listed here have survived and are open to the public.

Germany

[edit]- Eisenhammer Dorfchemnitz (museum)

- Erla Ironworks

- Freibergsdorf Hammer Mill (open to the public)

- Frohnauer Hammer (museum)

- Pfeilhammer

The Bavarian Iron Route (Bayerische Eisenstraße) is an important holiday route in southern Germany that is rich in history. It runs for 120 kilometres, linking numerous historical industrial sites, which represent several centuries, with cultural and natural monuments. The Bavarian Iron Route runs along old transport routes from the Nuremberg Region near Pegnitz southwards to Regensburg and links the former iron centres of East Bavaria, namely the mining regions of Pegnitz, Auerbach, Edelsfeld, Sulzbach-Rosenberg and Amberg. From there it becomes a waterway, about 60 km long, on the rivers Vils and Naab until they empty into the Danube near Regensburg.

- Hammer mill in Eckersmühlen (museum)

- Hammer forges on the Gronach near Gröningen (Satteldorf), Hohenlohe

- Iron smeltery and hammer mill in Peitz (museum)

- Hammer and bell forge in Ruhpolding (museum)

- Upper Bergisches Land

- Oelchenshammer (museum)

- Gaisthaler Hammer

- The Mining and Industrial Museum of East Bavaria (Bergbau- und Industriemuseum Ostbayern) in Theuern (in the municipality of Kümmersbruck) is a nationally important museum, which has researched and documented the mining and other industries of the entire East Bavarian region. The museum was established in 1978 in the old hammer lord castle of Theuern. The museum area includes the schloss and three other industrial monuments typical of the region which were transported to Theuern. One of the outer sites of the museum is the Staubershammer Hammer Mill. The mill was dismantled in 1973 in the vicinity of Auerbach and rebuilt in its original state in Theuern. Most of its facilities date to the late 19th century.

- Deilbachhammer (museum)

- Bremecker Hammer Lüdenscheid (museum)

- Luisenhütte (museum)

- Oberrödinghauser Hammer (museum)

- Wendener Hütte (museum)

- historic hammer forge in Blaubeuren (museum)

- Eisenhammer in Hasloch (museum)

- Tobiashammer (museum)

- Eisenhammer Weida (museum, working mill)

- historic hammer forge in Dassel (museum)

- Unterer Eisenhammer Exten (museum)

Austria

[edit]- Forge museum Arbesbach

- Austrian Iron Route

- Between Lassing and Hollenstein an der Ybbs lies in the Hammerbach valley. Here the remains of old hammer mills may be seen including the Hof-Hammer, Wentsteinhammer, Pfannschmiede and Treffenguthammer.

- Along Blacksmiths' Mile (Schmiedemeile) in Ybbsitz there are several hammer mills, the Fahrngruber Hammer, the Hammerwerk Eybl and workshop, the Strunz Hammer and the Einöd Hammer. the unique cultural ensemble of iron and metalworking was incorporated into the register of cultural heritage in Austria in 2010.[7])

- In Vordernberg, as well as visiting historic blast furnaces known as Radwerken, the educational finery forge may be seen. This gives the flavour of an old smithy with its fully functional trip hammer driven by a water wheel. This hammer was used mainly for demonstration purposes.

Culture

[edit]In the literature, hammer mills were immortalised in Friedrich Schiller's ballad, Der Gang nach dem Eisenhammer (1797), which Bernhard Anselm Weber set to music for the actor, August Wilhelm Iffland, as a great orchestral melodrama, and later by Carl Loewe as a through-composed ballad.

See also

[edit]- Stamp mill - a premises that usually used drop hammers to crush ore

References

[edit]- ^ Agricola, Georgius (1556): De re metallica libri XII. - Basel.

- ^ [1]. Erläuterung "Verstählen". At www.enzyklo.de. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ^ Herbert Nicke: Bergische Mühlen – Auf den Spuren der Wasserkraftnutzung im Land der tausend Mühlen zwischen Wupper und Sieg; Galunder; Wiehl; 1998; ISBN 3-931251-36-5.

- ^ Klaus Altenbuchner, Michael A. Schmid: Das Hammerschloss in Schmidmühlen. Zur Wiederentdeckung eines italienisch geprägten Schlosses und seiner bedeutenden Dekoration. In: Verhandlungen des Historischen Vereins für Oberpfalz und Regensburg. Vol. 143, 2003, ISSN 0342-2518, pp. 397–418.

- ^ Combe, Paul (1922). "Thiers et la vallée industrielle de la Durolle". Annales de géographie. 31 (172): 360–365. doi:10.3406/geo.1922.10136.

- ^ Abinger Hammer Mill Archived 2018-03-07 at the Wayback Machine at www.tillingbournetales.co.uk. Retrieved 30 Apr 2017.

- ^ Schmieden in Ybbsitz Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

Literature

[edit]- Gaspard L. de Courtivron, Étienne Jean Bouchu: Abhandlung von den Eisenhammern und hohen Oefen. Aus dem Französischen der "Descriptions des arts & metiers" translated with footnotes by Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi. Rüdiger, Berlin, Stettin and Leipzig, 1763 (e-book. s. n., Potsdam 2010, ISBN 978-3-941919-72-3).

- Lothar Klapper: Geschichten um Hütten, Hämmer und Hammermeister im mittleren Erzgebirge. Ein Vortrag zur Geschichte ehemaliger Hütten und Hämmer im Landkreis Annaberg (= Streifzüge durch die Geschichte des oberen Erzgebirges 32, ZDB-ID 2003414-3). Vol. 1. Neuer Heimatkundlicher Arbeitskreis, Annaberg-Buchholz, 1998, online publication Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Bernd Schreiter: Hammerwerke im Preßnitz- und Schwarzwassertal (= Weisbachiana. Heft 27, ZDB-ID 2415622-X). 2nd revised edition. Verlag Bernd Schreiter, Arnsfeld, 2006.

- Johann Christian zu Solms-Baruth, Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi: Abhandlung von den Eisenhammern und hohen Oefen in Teutschland. Rüdiger, Berlin, Stettin and Leipzig 1764 (E-Book. Becker, Potsdam, 2010, ISBN 978-3-941919-73-0).

- E. Erwin Stursberg: Geschichte des Hütten- und Hammerwesens im ehemaligen Herzogtum Berg (= Beiträge zur Geschichte Remscheids. Issue 8, ISSN 0405-2056). Town archives, Remscheid, 1964.

External links

[edit]- Bavarian Iron Route

- Mining and Industrial Museum of East Bavaria

- Cultural landscape of the Deilbach Valley

- Photographs of the Erft Hammer Mill

- Burghausen Hammer Forge (recorded since 1465)

- Literature database on historic mining, smelting and salt works

- Oberer Eisenhammer in Exten[permanent dead link]

- Fahrngruber Hammer in Ybbsitz (Austria) Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine