Hambantota

The factual accuracy of parts of this article (those related to article) may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (August 2017) |

Hambantota

හම්බන්තොට அம்பாந்தோட்டை | |

|---|---|

Hambantota Administrative Complex | |

| Nickname: Hamba City | |

| Coordinates: 06°07′28″N 81°07′21″E / 6.12444°N 81.12250°E | |

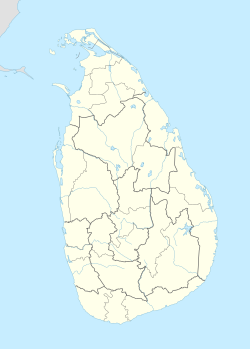

| Country | Sri Lanka |

| Province | Southern Province |

| District | Hambantota District |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipal Council |

| • Mayor | vacant |

| Elevation | 1 m (3 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

• Total | 57,264 |

| Time zone | +05:30 |

| Postal Code | 82xxx |

| Area codes | 047 |

Hambantota (Sinhala: හම්බන්තොට, Tamil: அம்பாந்தோட்டை) is the main city in Hambantota District, Southern Province, Sri Lanka.

This underdeveloped area was hit hard by the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and is undergoing a number of major development projects including the construction of a new sea port and international airport finished in 2013. These projects and others such as Hambantota Cricket Stadium are said to form part of the government's plan to transform Hambantota into the second major urban hub of Sri Lanka, away from Colombo.[1]

History

[edit]When the Kingdom of Ruhuna was established it received many travellers and traders from Siam, China and Indonesia who sought anchorage in the natural harbor at Godawaya, Ambalantota. The ships or large boats these traders travelled in were called "Sampans" and thota means port or anchorage so the port where sampans anchor came to be known as Sampantota. After some time the area came to be called Hambantota.[2]

Hambantota is derived from 'Sampan Thota' – the harbour used by Malay sea going Sampans which traversed the southern seas in the 1400s well before the European colonisers arrived.

The prominent Malay community part of the population is said to be partly descended from seafarers from the Malay Archipelago who travelled through the Magampura port, and over time settled down.

The presence of a pre-existing Malay community prompted the British colonial Government to disband and settle soldiers of a Malay Regiment which had fought with the British in the Kandyan wars at Kirinda near Hambantota. After the arrival of the European colonialists, and the focus of the Galle harbour, Hambantota went into quiet decline.

Ancient Hambantota

[edit]Hambantota District is part of the traditional south known as Ruhuna. In ancient times this region, especially Hambantota and the neighboring areas was the centre of a flourishing civilization. Historical evidence reveals that the region in that era had fertile fields and a stupendous irrigation network. Hambantota was known by many names Mahagama, Ruhuna and Dolos dahas rata.

About 200 BC, the first Kingdom of Sri Lanka was flourishing in the north central region of Anuradhapura.

After a personal dispute with his brother, King Devanampiyatissa of Anuradhapura, King Mahanaga established the Kingdom of Ruhuna in the south of the island. This region played a vital role in building the nation as well as nurturing the Sri Lankan Buddhist culture. Close to Hambantota, the large temple of Tissamaharama was built to house a sacred tooth relic.[3]

Modern history

[edit]Around the years of 1801 and 1803, the British built a Martello tower on the tip of the rocky headland alongside the lighthouse overlooking the sea at Hambantota. The builder was a Captain Goper, who built the tower on the site of an earlier Dutch earthen fort. The tower was restored in 1999, and in the past, formed part of an office of the Hambantota Kachcheri where the Land Registry branch was housed. Today it houses a fisheries museum.

From 2 August to 9 September 1803, an Ensign J. Prendergast of the regiment of Ceylon native infantry was in command of the British colony at Hambantota during a Kandian attack that he was able to repel with the assistance of the snow ship Minerva.[4] Earlier, HMS Wilhelmina had touched there and left off eight men from the Royal Artillery to reinforce him.[5] This detachment participated in Prendergast's successful defense of the colony.[6] If the tower at Hambantota was at all involved in repelling any attack this would be one of the only cases in which a British Martello tower had been involved in combat.

Leonard Woolf, future husband of Virginia Woolf, was the British colonial administrator at Hambantota between 1908 and 1911.

2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

[edit]The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami devastated Hambantota, and reportedly killed more than 4500 people.[7]

Climate

[edit]Hambantota features a tropical wet and dry climate (As) under the Köppen climate classification. There is no true dry season, but there is significantly less rain from January through March and again from June through August. The heaviest rain falls in October and November. The city sees on average roughly 1,050 millimetres (41 in) of precipitation annually. Average temperatures in Hambantota change little throughout the year, ranging from 26.3 °C (79.3 °F) in January to 28.1 °C (82.6 °F) in April and May.

| Climate data for Hambantota (1991–2020, extremes 1869–2021) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34.7 (94.5) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.0 (96.8) |

37.5 (99.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.2 (99.0) |

36.2 (97.2) |

39.2 (102.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.7 (98.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

39.2 (102.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 30.9 (87.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.9 (89.4) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.2 (88.2) |

31.6 (88.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.4 (86.7) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.1 (80.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.7 (83.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

27.9 (82.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.2 (77.4) |

25.0 (77.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.4 (63.3) |

18.9 (66.0) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 68.4 (2.69) |

47.4 (1.87) |

47.0 (1.85) |

92.3 (3.63) |

73.1 (2.88) |

41.2 (1.62) |

30.8 (1.21) |

59.4 (2.34) |

100.0 (3.94) |

128.5 (5.06) |

221.8 (8.73) |

132.1 (5.20) |

1,041.7 (41.01) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5.3 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 5.6 | 4.3 | 6.3 | 8.3 | 10.1 | 13.0 | 9.4 | 84.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at Daytime) | 71 | 71 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 77 | 75 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 77 | 76 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 207.7 | 200.6 | 248.0 | 237.0 | 235.6 | 201.0 | 204.6 | 201.5 | 207.0 | 192.2 | 189.0 | 217.0 | 2,541.2 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.7 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Source 1: NOAA[8] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher Wetterdienst (precipitation days, 1968–1990 and sun, 1962–1977),[9] Meteo Climat (record highs and lows)[10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Hambantota Town is Buddhist majority. Islam is the second largest religion in the town. There are also small numbers of Christians and Hindus. Sinhalese people form the majority of the town's population followed by Sri Lankan Malays who make up 30% of the total population.[11]

Religion in Hambantota[12]

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]A cement grinding and bagging factory is being set up, as well as fertiliser bagging plants. Large salt plains are a prominent feature of Hambantota. The town is a major producer of salt.[3] A Special Economic Zone of 6,100 hectares (15,000 acres) has been proposed by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, out of which approximately 500 hectares (1,235 acres) will be situated in Hambantota to build factories, LNG plants and refineries while the rest will be in Monaragala, Embilipitiya and Matara.[13][14][15] A Vocational training Center was opened in 2017 by Prime minister Ranil Wickremesinghe with China to train the workforce needed for the SEZs.[16] Wickramasinghe also came into an agreement with state-owned China Merchants Port Holdings to lease 70 per cent stake of the strategically-located Hambantota port at $1.12 billion, opening Hambantota to the Belt and Road Initiative.[17]

Transportation

[edit]Air

[edit]Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA) is located in the town of Mattala, 18 km (11 mi) north of Hambantota. Opened in March 2013, it is the second international airport in Sri Lanka after Bandaranaike International Airport in Colombo.[18] The Weerawila Airport is also located nearby.[19]

Road

[edit]A2 highway connects Colombo with Hambantota town through Galle and Matara. The Southern Expressway from Kottawa to Matara will be connected to Hambantota via Beliatta.

Rail

[edit]Construction work started in 2006 on the Matara-Kataragama Railway Line project, a broad gauge railway being implemented at an estimated cost of $91 million.[20]

Energy

[edit]

The Hambantota Wind Farm is the first wind farm in Sri Lanka (there are two more commercial wind farms).[21] It's a pilot project to test wind power generation in the island nation.[22] Wind energy development faces immense obstacles such as poor roads and an unstable power grid. With the transmission network development plan of CEB, first ever 220kV grid substation is under construction in Hambantota, it will be connected to the National Grid by 2022. CHINT Electric is the Main Contractor and Minel Lanka is the National Contractor that carried out design, civil construction and electrical installation works. This substation will be handling 500 MVA with 6 units of 220/132/33 kV 83.33 MVA power transformers from Tirathai.[23]

Port

[edit]

Hambantota is the selected site for a new international port, the Port of Hambantota. It was scheduled to be built in three phases, with the first phase due to be completed by the end of 2010 at a cost of $360 million.[24] As part of the port, a $550 million tax-free port zone is being started, with companies in India, China, Russia and Dubai expressing interest in setting up shipbuilding, ship-repair and warehousing facilities in the zone. The port officially opened on November 18, 2010, at the end of the first phase of construction.[25] When all phases are fully complete, it will be able to berth 33 vessels, which would make it the biggest port in South Asia.[26]

Bunkering facility: 14 tanks (8 for oil, 3 for aviation fuel and 3 for LP gas) with a total capacity of 80,000 m3 (2,800,000 cu ft).[27] But in the whole of 2012 only 34 ships berthed at Hambantota, compared with 3,667 ships at the port of Colombo.[25] Sri Lanka was still heavily in debt to China for the cost of the port and with so little traffic, was unable to service the debt.[28] In 2017 China was given a 99-year lease for the port in exchange for $1.1 billion.[29]

The involvement of Chinese companies in the development of Hambantota port have provoked claims by some analysts that it is part of China's String of Pearls strategy. Other analysts have argued that it would not be in Sri Lanka's interests to allow the Chinese navy access to the port and in any event the exposed nature of the port would make it of dubious value to China in time of conflict.[30]

In November 2019, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa indicated that the Sri Lankan government would try to undo the 99-year lease of the port and return to the original loan repayment schedule.[29][31] As of August 2020 the 99-year lease was still in place.[32]

Culture

[edit]Hambantota contains the Mahinda Rajapaksa International Stadium[33] for sports activities. It has a capacity of 35,000 seats and was built for the 2011 Cricket World Cup. The cost of this project is an estimated Rs. 900 million (US$7.86m). Sri Lanka Cricket is seeking relief from its debts incurred in building infrastructure for the 2011 Cricket World Cup.[1]

Magam Ruhunupura International Conference Hall (MRICH) was built for local and international events. The MRICH, situated in a 28-acre plot of land in Siribopura, is Sri Lanka's second international conference hall. The main hall has 1,500 seats and there are three additional halls with a seating capacity of 250 each. The conference hall is fully equipped with modern technical facilities and a vehicle park for 400 vehicles and a helipad for helicopter landing.[34]

On 31 March 2010, a surprise bid was made for the 2018 Commonwealth Games by Hambantota. Hambantota is undergoing a major face lift since the tsunami. On 10 November 2011, the Hambantota bidders claimed they had already secured enough votes to win the hosting rights.[35] However, on 11 November it was officially announced that Australia's Gold Coast had won the rights to host the games.[36][37]

Twin cities

[edit]Hambantota is twinned with Guangzhou, China, since 2007.[38]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Fernando, Andrew Fidel (April 5, 2013). "SLC expects financial assistance from government". ESPNCricinfo. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Hambantota". Hambantota District Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b "Hambantota District. Hambantota: Sri Lanka's Deep South". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2012-07-25.

- ^ The Asiatic annual register, or, A View of the history of ..., Volume 8, Issue 1, p.74.

- ^ "No. 15689". The London Gazette. 3 April 1804. p. 405.

- ^ Stubbs, Francis W. (January 2010). History of the Organization, Equipment, and War Services of the Regiment of Bengal Artillery. General Books. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-150-23818-5.

- ^ "Divisions over tsunami new town". BBC. 17 March 2005. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Hambantota". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Hambantota / Sri Lanka (Ceylon)" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Station Hambantota" (in French). Meteo Climat. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ Nordhoff, Sebastian (2012). The Genesis of Sri Lanka Malay: A Case of Extreme Language Contact. Brill Publishers. p. 3.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing 2012". statistics.gov.lk. Department of Census and Statistics, Sri Lanka. 2012.

- ^ "economynext.com". www.economynext.com. Archived from the original on 2018-08-07. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka launches special industrial zone to attract Chinese industries". Colombo Page. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "US $ 5 b investment in Hambantota: 1,235 acres for industrial zone". Sunday Observer. 2017-01-07. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Sri Lanka, China open training center to support southern development – Xinhua | English.news.cn". news.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2017-01-09.

- ^ "Hambantota Port agreement to be signed tomorrow - PM".

- ^ "Overview of Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport (MRIA)". www.airport.lk/. Archived from the original on 2018-04-10.

- ^ "(WRZ) Weerawila Airport". FlightStats. Archived from the original on 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

- ^ Massive Development in Hambantota District Archived 2011-07-22 at the Wayback Machine, Media Centre for National Development in Sri Lanka, retrieved 2010-01-19

- ^ "Sri Lanka's first commercial wind energy plant to start - LANKA BUSINESS ONLINE". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "3 MW Pilot Wind Power Project at Hambantota". Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ^ "Minel Lanka Projects". Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ Shirajiv Sirimane (21 February 2010). "Hambantota port, gateway to world". Sunday Observer. Archived from the original on 24 February 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ a b Abi-Habib, Maria (25 June 2018). "How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ Ondaatjie, Anusha (8 March 2010). "Sri Lanka to Seek Tenants for $550 Million Tax-Free Port Zone". Business Week. Archived from the original on March 11, 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ "Sri Lanka: Sri Lanka\'s Hambantota Harbor refuels six ships in two weeks". www.colombopage.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-10.

- ^ Stacey, Kiran (11 December 2017). "China signs 99-year lease on Sri Lanka's Hambantota port". Financial Times. ft.com. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ a b Asantha Sirimanne, Anusha Ondaatjie (30 November 2019). "Sri Lanka leased Hambantota port to China for 99 yrs. Now it wants it back". Business Standard. Business Standard Ltd. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ David Brewster. "Beyond the String of Pearls: Is there really a Security Dilemma in the Indian Ocean?. Retrieved 11 August 2014".

- ^ Ondaatjie, Anusha; Sirimanne, Asantha (28 November 2019). "Sri Lanka Wants to Undo Deal to Lease Port to China for 99 Years". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019.

We would like them to give it back," Ajith Nivard Cabraal, a former central bank governor and an economic adviser to Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, said in an interview at his home in a Colombo suburb. "The ideal situation would be to go back to status quo. We pay back the loan in due course in the way that we had originally agreed without any disturbance at all.

- ^ Saeed Shah, Asiri Fernando (7 August 2020). "Pro-China Populists Consolidate Power in Sri Lanka". The Wall Street Journal. wsj.com. Retrieved 2020-08-08.

- ^ "Mahinda Rajapaksa International Cricket Stadium | Sri Lanka | Cricket Grounds | ESPNcricinfo.com". Cricinfo. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ^ "President opens international convention center in Hambantota ahead of CHOGM | DailyFT - Be Empowered". www.ft.lk. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11.

- ^ Ardern, Lucy (11 November 2011). "Sri Lanka boasting of Games bid win". Gold Coast Bulletin. Archived from the original on 24 December 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Candidate City Manual" (PDF). Commonwealth Games Federation. December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Ardern, Lucy (13 November 2011). "Coast wins 2018 Commonwealth Games". Gold Coast Bulletin. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ "Guangzhou Sister Cities [via WaybackMachine.com]". Guangzhou Foreign Affairs Office. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-21.

- Stubbs, Francis W. (1877) History of the organization, equipment, and war services of the regiment of Bengal artillery : compiled from published works, official records, and various private sources. (Henry S. King & Co.).