Hale (Martian crater)

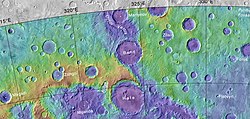

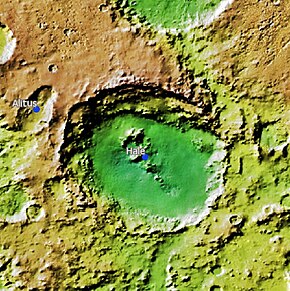

Topographic map of Hale Crater | |

| Planet | Mars |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 35°42′S 323°24′E / 35.7°S 323.4°E |

| Quadrangle | Argyre |

| Diameter | 137.5 km |

| Eponym | George Ellery Hale |

Hale is a 150 km × 125 km (93 mi × 78 mi) crater at 35.7°S, 323.4°E on Mars, just north of Argyre basin. The crater is in the Argyre quadrangle. It was named after American astronomer George Ellery Hale.[1]

Description

[edit]On 28 September 2015 NASA confirmed the seasonal existence of liquid water in Hale crater.[2] The salts in the water (magnesium perchlorate, magnesium chlorate, sodium perchlorate,...) lower its freezing and melting point to 203 K (−70 °C or −94 °F), which is near the average summer night temperature. Hale was created by an asteroid roughly 35 km (22 mi) across that impacted at an oblique angle about 3.5–3.8 billion years ago. The rim and ejecta are eroded and show smaller impacts, but subsequent deposits have covered up small craters within it.[3] On the southern rim of Hale, parts of the crater wall have moved downslope towards the crater's centre. The surface shows a network of fluvial channels which may have been caused by running water.[4] It is named after George Ellery Hale.

The wall of Hale Crater has many gullies. Some are pictured below in an image from HiRISE. Unlike, some other gullies on Mars, these are in light-toned materials. Research published in the journal Icarus has found pits in Hale Crater that are caused by hot ejecta falling on ground containing ice. The pits are formed by heat forming steam that rushes out from groups of pits simultaneously, thereby blowing away from the pit ejecta.[5]

Gullies occur on steep slopes, especially craters. Gullies are believed to be relatively young because they have few, if any craters, and they lie on top of sand dunes which are young. Usually, each gully has an alcove, channel, and apron. Although many ideas have been put forward to explain them, the most popular involve liquid water either coming from an aquifer or left over from old glaciers.[6]

There is evidence for both theories. Most of the gully alcove heads occur at the same level, just as one would expect of an aquifer. Various measurements and calculations show that liquid water could exist in an aquifer at the usual depths where the gullies begin.[7] One variation of this model is that rising hot magma could have melted ice in the ground and caused water to flow in aquifers. Aquifers are layer that allow water to flow. They may consist of porous sandstone. This layer would be perched on top of another layer that prevents water from going down (in geological terms it would be called impermeable). The only direction the trapped water can flow is horizontally. The water could then flow out onto the surface when it reaches a break, like a crater wall. Aquifers are quite common on Earth. A good example is "Weeping Rock" in Zion National Park Utah.[8]

-

Topo map showing the location of Hale Crater and other nearby features

-

Gullies on Hale Crater Wall, as seen by HiRISE.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hale". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- ^ Akpan, Nsikan (September 2015). "Mars has flowing rivers of briny water, NASA satellite reveals". PBS NewsHour.

- ^ Naeye, Robert (June 2005). "Mars's Hale Crater". Sky and Telescope. 109 (6): 30. Bibcode:2005S&T...109f..30N. Archived from the original on February 20, 2007. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

- ^ ESA – Mars Express – Crater Hale in Argyre basin

- ^ Tornabene, L. et al. 2012. Widespread crater-related pitted materials on Mars. Further evidence for the role of target volatiles during the impact process. Icarus. 220: 348–368.

- ^ Heldmann, J. and M. Mellon. Observations of Martian gullies and constraints on potential formation mechanisms. 2004. Icarus. 168: 285–304.

- ^ Heldmann, J. and M. Mellon. 2004. Observations of Martian gullies and constraints on potential formation mechanisms. Icarus. 168:285–304

- ^ Harris, A and E. Tuttle. 1990. Geology of National Parks. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. Dubuque, Iowa

External links

[edit]- Perspective views of the crater Hale from Mars Express

- Gullies in Hale crater

- High resolution videos by Seán Doran of flyovers of the gullied slopes of Hale, and of the hills within it