Hair bleaching

Hair bleaching is the practice of lightening the hair color, mainly for cosmetic purposes using bleaching agents. Bleaching can be done alone, combined with a toner, or as a step for further hair coloring. The most common commercial bleaching agents in use are hydrogen peroxide and persulfate salts, but historically other agents such as sulfuric acid, wood ash, lye and hypochlorite bleach were used. Hair can also become bleached unintentionally, such as through sun exposure.

History

[edit]During the early years of the Roman Empire, blond hair was associated with prostitutes.[1] The preference changed to bleaching the hair blond when Greek culture, which practiced bleaching, reached Rome, and was reinforced when the legions that conquered Gaul returned with blond slaves.[2] Sherrow states that Roman women tried to lighten their hair, but the substances often caused hair loss, so they resorted to wigs made from the captives' hair.[3] The bleaching agent used by the Roman women was composed of a solution of ashes from burnt nuts or plants.[4]

Diodorus Siculus, a 1st century BC Greek historian, described in detail how Celtic people bleached their hair: "Their aspect is terrifying... They are very tall in stature, with rippling muscles under clear white skin. Their hair is blond, but not naturally so: they bleach it, to this day, artificially, washing it in lime and combing it back from their foreheads. They look like wood-demons, their hair thick and shaggy like a horse's mane. Some of them are clean-shaven, but others—especially those of high rank—shave their cheeks but leave a moustache that covers the whole mouth...".[5][6]

During the medieval period, Spanish women preferred to dye their hair black, yet by the time of the Renaissance in the 16th century the fashion (imported from Italy) was to bleach their hair blond or dye it red.[7] Between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, a number of dangerous hair bleaching methods remained widely practiced, including the use of sulfuric acid, which was an accepted form of hair coloring around the 1600s, and laying out in the sun with hair covered in lye a century later.[4]

In Sir Hugh Plat's 1602 work Delightes for Ladies, the use of oil of vitriol (sulfuric acid) to bleach black hair to chestnut is described as: "Take one part of lead calcined with Sulphur, and one part of quicklime: temper them somewhat thin with water: lay it upon the hair, chafing it well in, and let it dry one quarter of an hour or thereasbouts; the wash the same off with fair water divers times: and lastly with sope and water, and it will be a very natural hair-colour. The longer it lyeth upon the haire, the browner it groweth. This coloureth not the flesh at all, and yet it lasteth very long in the hair."[8]

Modern history

[edit]Howard Hughes' 1931 movie Platinum Blonde starring Jean Harlow is noted to have popularized platinum blonde hair color in the US. After the movie's success Hughes's team established a chain of "Platinum Blonde clubs" in several cities and offered a $10,000 prize that would go to any hairdresser who could copy Harlow's shade.[9] Though Harlow denied her hair was bleached,[10] the platinum blonde color was reportedly achieved with a weekly application of ammonia, Clorox bleach, and Lux soap flakes. This process weakened and damaged Harlow's naturally ash-blonde hair.[11]

During the 1930s Lawrence M. Gelb advanced the formulas of the bleaching products. In 1950, Clairol, the company Gelb founded with wife Jane Clair, introduced the first one-step hair dye product that lightened hair, which became a huge success with the masses.[9]

In the early 1990s a trend emerged of eyebrow bleaching from the fashion world. Creatives such as Alexander McQueen, Anna Sui, and Pat McGrath had models like Linda Evangelista bleaching their eyebrows. Entertainers Jared Leto and Madonna, as well as club goers at the time, went on to do the same. Kevyn Aucoin's 1997 book Making Faces, gave a tutorial on how to do so. The trend continued on into the early 2000s and reemerged in the early 2020s as homage to Y2K fashion.[12][13][14]

Bleaching process

[edit]Using bleaching agents

[edit]Melanin pigments, which give hair a darker color, can be broken down with oxidation.[15] Most commercial bleaching formulas contain hydrogen peroxide and persulfate salts, which under alkaline conditions created by ammonia or monoethanolamine can bleach the hair. Persulfate salts, in combination with hydrogen peroxide or alone, are known for their ability to degrade organics after activation with heat, transition metals, ultraviolet light, or other means that produce the sulfate radical. Without activation, the persulfate anion is known to react with some organic chemicals, although with slow kinetics.[16] When melanin is oxidized, oxygen gas is released.[15] Products for bleaching one's hair at home usually contain a 6% solution of hydrogen peroxide, while products for use in a hair salon can contain up to 9%.[15] Hair bleaching products can damage hair and cause severe burns to the scalp when applied incorrectly or left on too long.[17]

Industrial bleaches that work by reduction (such as sodium hydrosulphite) react with a chromophore, the part of the molecule responsible for its color and decrease the number of carbon-oxygen bonds in it, making it uncoloured. This process might be reversed to a certain extent by oxygen in the air, such as yellowing of bleached paper if left uncovered. In contrast, hydrogen peroxide chemically alters the chromophore by increasing the number of carbon-oxygen bonds. Due to the relative absence of reducing agents in the environment, chromophores cannot restore themselves as seen in reduction-based bleaches.[18]

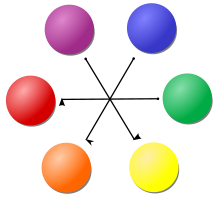

Bleaching the hair is a gradual process and different colors may be achieved dependent on the original hair color, application time, and strength of the product used. Applied on black hair, the hair will change its color to brown, red, orange, orange-yellow, yellow, and finally pale yellow.[19]

Toner

[edit]

Toning is a common practice after bleaching to mask the undesirable red and orange tones of "brassy" hair using a toner dye. Through toning, the yellow hue of fully bleached hair can be removed to achieve platinum blond hair. The appropriate color of the toner depends on the color of the bleached hair; e.g. to remove the yellow tones a violet toner dye will be needed, but to neutralize red and orange hues a green/blue toner would be more suitable. Tinted shampoos can also be used to tone hair.[19][20]

Sun exposure

[edit]Excessive exposure to the sun is the most common cause of structural damage of the hair shaft. Photochemical hair damage encompasses hair protein degradation and loss, as well as hair pigment deterioration[21] Photobleaching is common among people with European ancestry. Around 72 percent of customers who agreed to be involved in a study and have European ancestry reported in a recent 23andMe research that the sun lightens their hair. The company also have identified 48 genetic markers that may influence hair photobleaching.[22]

Medical significance

[edit]Drug testing methods using hair samples are found to be disrupted by chemical hair treatments including bleaching. According to a 2019 study bleaching has caused strong chemical degradation on cannabinoids in hair, while permanent colorings in single applications had only negligible effects on cannabinoids.[23] A 2021 study found similar results for methamphetamine concentrations in hair.[24]

Persulfate containing products may produce a variety of cutaneous and respiratory responses, such as allergic eczematous contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, localized edema, generalized urticaria, rhinitis, asthma, dizziness, and syncope.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ Sherrow 2006, p. 148.

- ^ Sherrow 2006, p. 149.

- ^ Victoria Sherrow, For Appearance' Sake: The Historical Encyclopedia of Good Looks, Beauty, and Grooming, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 136, Google Books

- ^ a b Pretzel, Jillian (2019-07-15). "Blonde Didn't Come From a Bottle: A short history of hair color". ARTpublika Magazine. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- ^ "The Celts". www.ibiblio.org. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ "Diodorus Siculus, Library of History - Exploring Celtic Civilizations". exploringcelticciv.web.unc.edu. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ Eric V. Alvarez (2002). "Cosmetics in Medieval and Renaissance Spain", in Janet Pérez and Maureen Ihrie (eds), The Feminist Encyclopedia of Spanish Literature, A–M. 153–155. Westport and London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29346-5, p. 154

- ^ Hull, Suzanne W. (1996). Women According to Men: The World of Tudor-Stuart Women. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7619-9119-9.

- ^ a b "From 1500 BC to 2015 AD: The Extraordinary History of Hair Color". Byrdie. Retrieved 2022-01-27.

- ^ Stenn 1993, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Sherrow 2006, p. 200.

- ^ Bateman, Kristen (2021-12-08). "How Bleached Eyebrows Became the Defining Beauty Trend of 2021". W Magazine. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ Sinay, Danielle (2022-09-13). "The Bleached-Eyebrows Renaissance Is Upon Us". Glamour. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ Lobad, Noor (2022-12-16). "Bleached Brows, Then and Now". WWD. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ a b c Zoe Diana Draelos (29 December 2004). Hair Care: An Illustrated Dermatologic Handbook. CRC Press. pp. 132–. ISBN 978-0-203-31424-1.

- ^ Gargano, Emanuele M.; Mangiatordi, Giuseppe F.; Weber, Ingo; Goebel, Carsten; Alberga, Domenico; Nicolotti, Orazio; Ruess, Wolfgang; Wierlacher, Stefan (2018-03-25). "Persulfate Reaction in a Hair-Bleaching Formula: Unveiling the Unconventional Reactivity of 1,13-Diamino-4,7,10-Trioxatridecane". ChemistryOpen. 7 (5): 319–322. doi:10.1002/open.201800013. ISSN 2191-1363. PMC 5931532. PMID 29744283.

- ^ Bouschon, P.; Bursztejn, A.-C.; Waton, J.; Brault, F.; Schmutz, J.-L. (May 2018). "Scalp burns induced by hair bleaching". Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 145 (5): 359–364. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2018.02.004. ISSN 0151-9638. PMID 29550112.

- ^ "Where does the colour go when I bleach my hair?". mcgill.ca.

- ^ a b Church, Charlotte; Read, Alison (2013-05-29). Hairdressing: Level 3: The Interactive Textbook. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-26014-8.

- ^ Davis, Gretchen (2016-01-22). The Hair Stylist Handbook: Techniques for Film and Television. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-317-59979-1.

- ^ Sebetić, Klaudija; Sjerobabski Masnec, Ines; Cavka, Vlatka; Biljan, Darko; Krolo, Ivan (October 2008). "UV damage of the hair". Collegium Antropologicum. 32 (Suppl 2): 163–165. ISSN 0350-6134. PMID 19138021.

- ^ "Hair Lightening from the Sun". 23andMe. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- ^ Van Elsué, Nicolas; Yegles, Michel (April 2019). "Influence of cosmetic hair treatments on cannabinoids in hair: Bleaching, perming and permanent coloring". Forensic Science International. 297: 270–276. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2019.02.030. ISSN 1872-6283. PMID 30851603. S2CID 73487690.

- ^ He, XinYu; Wang, Ji Fen; Wang, Yanyan (2021-10-01). "Influence of cosmetic hair treatments on hair of methamphetamine abuser: Bleaching, perming and coloring". Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 222: 112542. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112542. ISSN 1090-2414. PMID 34311424.

- ^ Fisher, A. A.; Dooms-Goossens, A. (October 1976). "Persulfate hair bleach reactions. Cutaneous and respiratory manifestations". Archives of Dermatology. 112 (10): 1407–1409. doi:10.1001/archderm.1976.01630340025007. ISSN 0003-987X. PMID 962335.

Sources

[edit]- Sherrow, Victoria, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hair: A Cultural History. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-3133-3145-9.

- Stenn, David (1993). Bombshell: The Life and Death of Jean Harlow. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-3854-2157-7.

Further reading

[edit]- Robbins, Clarence R. (2006-05-26). Chemical and Physical Behavior of Human Hair. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-21695-9.