Slave ship

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast in West Africa.[2]

Atlantic slave trade

[edit]In the early 1600s, more than a century after the arrival of Europeans to the Americas,[3] demand for unpaid labor to work plantations made slave-trading a profitable business. The Atlantic slave trade peaked in the last two decades of the 18th century, during and following the Kongo Civil War.[4]

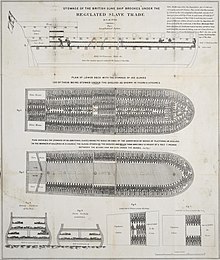

To ensure profitability, the owners of the ships divided their hulls into holds with little headroom, so they could transport as many slaves as possible. Unhygienic conditions, dehydration, dysentery, and scurvy led to a high mortality rate, on average 15%[5] and up to a third of captives. Often, the ships carried hundreds of slaves, who were chained tightly to plank beds. For example, the slave ship Henrietta Marie carried about 200 slaves on the long Middle Passage. They were confined to cargo holds, with each slave chained with little room to move.[6]

The most significant routes of the slave ships led from the north-western and western coasts of Africa to South America and the south-east coast of what is today the United States, and the Caribbean. As many as 20 million Africans were transported by ship.[7] The transportation of slaves from Africa to America was known as the Middle Passage of the triangular trade.

Conditions on slave ships

[edit]Slaves

[edit]

The owners of slave ships embarked as many slaves as possible to make the voyage more profitable. They did so by cramming, chaining, and selectively grouping slaves to maximize the use of space. Slaves began to die of lack of oxygen due to these cramped conditions. Portuguese lawmakers passed the Tonnage Act of 1684 in order to slightly improve conditions.[8] Slaves on board were underfed and brutally treated, causing many to die before even arriving at their destination; dead or dying slaves were dumped overboard. An average of one to two months was needed to complete the journey. The slaves were naked and shackled together with several different types of chains, stored on the floor beneath bunks with little to no room to move. Some captains assigned slave guardians to watch over and keep the other slaves in check. They spent a large portion of time pinned to floorboards, which would wear skin on their elbows down to the bone. Diseases such as dysentery, diarrhea, ophthalmoparesis, malaria, smallpox, yellow fever, scurvy, measles, typhoid fever, hookworm, tapeworm, sleeping sickness, trypanosomiasis, yaws, syphilis, leprosy, elephantiasis, and melancholia resulted in the deaths of slaves on board slave ships.[9] Firsthand accounts from former slaves, such as Olaudah Equiano, describe the horrific conditions that slaves were forced to endure.[10]

The Slave Trade Act 1788, also known as Dolben's Act, regulated conditions on board British slave ships for the first time since the slave trade started. It was introduced to the United Kingdom Parliament by Sir William Dolben, an advocate for the abolition of slavery. For the first time, limits were placed on the number of slaves that could be carried. Under the terms of the act, ships could transport 1.67 slaves per ton up to a maximum of 207 tons burthen, after which only one slave per ton could be carried.[11] The well-known slave ship Brookes was limited to carrying 454 people; it had previously transported as many as 609 enslaved.[1] Olaudah Equiano was among the supporters of the act, but it was opposed by some abolitionists, such as William Wilberforce, who feared it would establish the idea that the slave trade simply needed reform and regulation, rather than complete abolition.[12] Slave counts can also be estimated by deck area rather than registered tonnage, which results in a lower number of errors and only 6% deviation from reported figures.[13]

This limited reduction in the overcrowding on slave ships may have reduced the on-board death rate, but this is disputed by some historians.[14]

Sailors and crew

[edit]In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the sailors on slave ships were often poorly paid and subject to brutal discipline and treatment.[15] Furthermore, a crew mortality rate of around 20% was expected during a voyage, with sailors dying as a result of disease, flogging, or slave uprisings.[16][17] While conditions for the crew were far better than those of the slaves, they remained harsh and contributed to a high death rate. Sailors often had to live and sleep without shelter on the open deck for the entirety of the Atlantic voyage, as the space below deck was occupied by slaves.[15]

Disease, specifically malaria and yellow fever, was the most common cause of death among sailors. A high crew mortality rate on the return voyage was in the captain's interests, as it reduced the number of sailors who had to be paid on reaching the home port.[17] Crew members who survived were frequently cheated out of their wages on their return.[15]

These aspects of the slave trade were widely known; the notoriety of slave ships amongst sailors meant those joining slave ship crews did so through coercion or because they could find no other employment. This was often the case for sailors who had spent time in prison.[18]

Black sailors are known to have been among the crews of British slave ships. These men came from Africa or the Caribbean, or were British-born. Dozens of individuals have been identified by researchers from surviving records. Knowledge of this is incomplete, though, as many captains did not record the ethnicity of crew members in their ship's muster roll.[19] African men (and occasionally African women) also served as translators.[20]

Abolition of the slave trade

[edit]

The African slave trade was outlawed by the United States and the United Kingdom in 1807. The 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act outlawed the slave trade throughout the British Empire. The U.S. law took effect on 1 January 1808.[21] After that date, all U.S. and British slave ships leaving Africa were seen by the law as pirate vessels subject to capture by the U.S. Navy or Royal Navy.[22] In 1815,[23] at the Council of Vienna, Spain, Portugal, France, and the Netherlands also agreed to abolish their slave trade. The trade did not end on legal abolition; between 1807 and 1860 British vessels captured 1,600 slave ships and freed 160,000 slaves.[24]

After abolition, slave ships adopted quicker, more maneuverable forms to evade capture by naval warships, one favorite form being the Baltimore Clipper. Some had hulls fitted with copper sheathing, which significantly increased speed by preventing the growth of marine weed on the hull, which would otherwise cause drag.[25] This was very expensive, and at the time was only commonly fitted to Royal Navy vessels. The speed of slave ships made them attractive ships to repurpose for piracy,[26] and also made them attractive for naval use after capture; USS Nightingale and HMS Black Joke were examples of such vessels. HMS Black Joke had a notable career in Royal Navy service and was responsible for capturing a number of slave ships and freeing many hundreds of slaves.

Attempts have been made by descendants of African slaves to sue Lloyd's of London for playing a key role in underwriting insurance policies taken out on slave ships bringing slaves from Africa to the Americas.[27]

See also

[edit]- List of slave ships

- Slave Coast, Gorée ("Slave island")

- Slave ship revolts

- Slave Trade Acts

References

[edit]- ^ a b Walvin 2011, p. 27.

- ^ "Guineaman" at Oxford English Dictionary; retrieved 24 October 2017

- ^ Native Americans Prior to 1492. Historycentral.com. Retrieved on 3 December 2015.

- ^ Thornton, John (1998). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (2nd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 304–5. ISBN 978-0-521-62217-2.

- ^ Mancke, Elizabeth and Shammas, Carole. The Creation of the British Atlantic World. 2005, pages 30-1

- ^ "History: The Middle Passages". The Middle Passage – A Slave Ship Speaks: The Wreck of the Henrietta Marie. Mel Fisher Maritime Heritage Society, Inc. Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2007). "Abolition and the Africa Trade". History Today. 57 (3): 20–27.

- ^ More, Anna (December 2022). "The Early Portuguese Slave Ship and the Infrastructure of Racial Capitalism". Social Text. 40 (4). Duke University Press: 23, 24. doi:10.1215/01642472-10013290. S2CID 257010396.

- ^ Sheridan, Richard B. (29 November 1981). "The Guinea Surgeons on the Middle Passage: The Provision of Medical Services in the British Slave Trade". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 14 (4): 601–625. doi:10.2307/218228. JSTOR 218228.

- ^ White, Deborah (2013). Freedom on My Mind. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. pp. 20, 21.

- ^ Cohn, Raymond (1985). "Deaths of Slaves in the Middle Passage". The Journal of Economic History. 45 (3): 685–692. doi:10.1017/s0022050700034604. JSTOR 2121762. PMID 11617312. S2CID 21327693.

- ^ Hochschild 2005, p. 140.

- ^ Garland, Charles; Klein, Herbert S. (April 1985). "The Allotment of Space for Slaves aboard Eighteenth-Century British Slave Ships". The William and Mary Quarterly. 42 (2): 238. doi:10.2307/1920430. ISSN 0043-5597. JSTOR 1920430.

- ^ Haines and Shlomowitz 2000, p. 58.

- ^ a b c Hochschild 2005, p. 114

- ^ Bernard Edwards; Bernard Edwards (Captain.) (2007). Royal Navy Versus the Slave Traders: Enforcing Abolition at Sea 1808–1898. Pen & Sword Books. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-1-84415-633-7.

- ^ a b Hochschild 2005, p. 94

- ^ Rediker 2007, p.138

- ^ Costello (2012), pp.71-72

- ^ Costello (2012), p. 101

- ^ "1807 U.S. Law on Slave Trade". 7 February 2006. Archived from the original on 7 February 2006. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- ^ "Slave Ships – The Last Slave Ships". Melfisher.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- ^ Timeline: The Atlantic Slave Trade. Exploring Amistad at Mystic Seaport

- ^ Sadler, Nigel (March 2008). "The Trouvadore Project: The Search for a Slave Ship and its Cultural Importance". International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 12 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1007/s10761-008-0056-8. ISSN 1092-7697. S2CID 162019007.

- ^ McCarthy, Mike (2005). Ships' Fastenings: From Sewn Boat to Steamship. Texas A&M University Press. p. 108. ISBN 978-1585444519.

- ^ "Real Pirates: The Untold Story of the Whydah from Slave Ship to Pirate Ship – National Geographic". Events.nationalgeographic.com. 14 December 2012. Archived from the original on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "Slave descendants to sue Lloyd's". BBC News. 29 March 2004. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Baroja, Pio (2002). Los pilotos de altura. Madrid: Anaya. ISBN 978-84-667-1681-9.

- Costello, R. (2012). Black salt : seafarers of African descent on British ships. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-767-5. OCLC 801365216.

- Hochschild, Adam (2006). Bury the chains : the British struggle to abolish slavery. London: Pan. ISBN 0-330-48581-4. OCLC 62225209.

- Rediker, Marcus (2007). The Slave Ship: A Human History. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-01823-9. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012.

- Walvin, James (2011). The Zong : a massacre, the law and the end of slavery. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18075-6. OCLC 758389538.

External links

[edit]- Paper on German Transatlantic trade, including list of slave ships (in German)

- Report of the Brown University Steering Committee on Slavery and Justice

- UNESCO — The Slave Route

- Voyages — The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database

- Slave Ships and the Middle Passage

- The Slave Trade

- Bristol UK Slave Ship Muster Roles