Guglielmo Marconi (Piccirilli)

Guglielmo Marconi Memorial | |

Guglielmo Marconi Memorial | |

| Location | 16th and Lamont Streets NW Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′36.96″N 76°59′58.2″W / 38.8936000°N 76.999500°W (Wrong Coordinates, actually at 38.93041077913263, -77.03672617619154) |

| Built | 1941 |

| Architect | Attilio Piccirilli (sculptor) Joseph Freedlander (architect) Joseph Gardner (landscape) |

| Part of | Mount Pleasant Historic District |

| NRHP reference No. | 78000256[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Designated | October 12, 2007 October 26, 1987 (Mount Pleasant Historic District) |

| Designated DCIHS | February 22, 2007 October 5, 1987 (Mount Pleasant Historic District) |

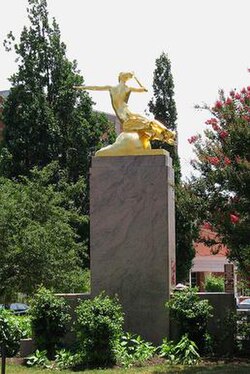

The Guglielmo Marconi Memorial is a public artwork by Attilio Piccirilli, located at the intersection of 16th and Lamont Streets NW in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C. It stands as a tribute to Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, whose work with telegraphy and radio waves led to the creation and popularity of the radio. It was paid for by public subscription and erected in 1941. The artwork was listed on both the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites and the National Register of Historic Places in 2007. It is a contributing property to the Mount Pleasant Historic District.

History

[edit]Biography

[edit]Guglielmo Marconi was born in 1874 in Bologna, Kingdom of Italy. His father was a businessman and his mother an Irish-born heiress. During his childhood, one of his neighbors was physicist Augusto Righi, whose work with electricity interested Marconi. Marconi was particularly interested in the work of physicist Heinrich Hertz. While still a young man, Marconi began his work in studying telegraphy and developing radio wave technology. In addition to Hertz, Marconi studied the works of physicist James Clerk Maxwell.[2]

Continuing his work with telegraphy and radio waves, in 1895, Marconi could send a message within a 1-mile (1.6 km) radius. Marconi attempted to notify the Ministry of Posts and Telegraphs, who had no interest in further developing the new technology. The following year Marconi was introduced to British post office engineer, Henry Jameson Davis. After the meeting, Marconi found success in using Hertz's laboratory, where he could demonstrate his work to others. Within the next few years, Marconi secured a patent for his invention and equipped a number of American ships with his wireless telegraph. He also founded the Wireless Telegraph & Signal Company and opened a fabricating warehouse in Chelmsford, England.[2][3]

Marconi built a transmitter station in Poldhu, England, and another in Wellfleet, Massachusetts. Due to technical problems, the latter station was moved to Glace Bay, Canada. On December 2, 1902, the first successful transmission of a wireless telegraph message was sent. The following month, he transmitted messages between President Theodore Roosevelt and King Edward VII.[2][3]

In the 1900s, Marconi quickly found success with the wireless telegraphs, installing them in cruise ships, and in 1909, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics along with Karl Ferdinand Braun. He was also awarded the Albert Medal by the Royal Society of Arts in 1914. Marconi continued to improve his invention, and it was later applied to radio communications. By the 1920s, a large number of European and American homes had a radio.[3]

He was appointed to be an Italian representative at the Paris Peace Conference, which took place after World War I. While there, he signed the Treaty of Versailles and other peace documents. He continued to work on his technology, but began having a series of heart attacks. Beginning in 1930, Marconi was appointed president of the Royal Academy of Italy by Benito Mussolini. As president of the organization, he was made a member of the Grand Council of Fascism.[2][3] Marconi died in 1937 after his ninth heart attack. He was given a state funeral[4]

Memorial

[edit]Within a few months after Marconi's death, there were calls for a memorial to be erected in his honor. On September 28, 1937, U.S. Representative Kent E. Keller asked the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) for their approval of a proposed memorial. Within a couple of weeks, the CFA approved the plan and suggested the memorial be erected in a prominent location.[5] The Marconi Memorial Foundation (MMF) was soon founded and began raising funds in 1938.[3] One of the earliest fundraisers took place at the Raleigh Hotel and featured opera stars singing in Italian, English, and Spanish.[6]

The sculptor chosen to create the memorial was Italian American Attilio Piccirilli, the architect was Joseph Freedlander, and the landscape was designed by Joseph Gardner.[7][8] After the final design was approved by the CFA, Congress approved a joint resolution to erect the memorial. The final bill was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on April 14, 1938.[5][9] In 1940, Congress approved the landscaping proposal and the inscriptions on the memorial. The following year the memorial site was approved by Congress.[10] The total cost of the memorial, $32,555, was raised by the MMF.[11][12]

After they had inspected the memorial, a MMF dinner attended by 150 guests took place at the Mayflower Hotel in July 1941. Amongst the attendees were Speakers of the House of Representative Sam Rayburn and Joseph W. Martin Jr., U.S. Senators James J. Davis and James M. Mead, U.S. Representatives Adolph J. Sabath and Samuel Dickstein, and Judge John J. Freschl, the MMF's vice president. Due to the ongoing World War II and Italy being one of the Axis powers, the dinner included speeches on uniting American citizens in a possible conflict. The statue was given to the federal government as a way of Italian Americans showing their loyalty to the U.S.[13] The timing of the memorial's dedication and the fact Marco was a proud supporter of Italian fascism made the event somewhat awkward.[14][15]

Later history

[edit]The Marconi memorial was added to the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites (DCIHS) on February 22, 2007, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on October 12, 2007. The memorial had previously been designated a contributing property to the Mount Pleasant Historic District on October 5, 1987 (DCIHS), and October 12, 2007 (NRHP).[16] A year before the memorial was individually listed, the bronze figures were re-gilded.[2]

Location and design

[edit]The Streamline Moderne-style memorial is located on the 0.23 acre (0.09 ha) Reservation 309A at the intersection of 16th and Lamont Streets NW in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of Washington, D.C.[2][17] It is sited in front of the Mount Pleasant Branch Public Library. Since the memorial is located on the north end of the reservation, and it is set at an angle, it is visible to people driving north on 16th Street NW. The surrounding landscape around the memorial includes bushes and turf.[2][8]

The sculpture features two bronze pieces. In the front is a bust of Marconi (approx. 40 x 30 x 16 in.; 102 x 76 x 42 cm) which sits on a rectangular Stony Creek granite base (200 x 182 x 54; 508 x 462 x 137 cm). Behind the bust is the second bronze (approx. 95 x 32 x 18 in.; 241 x 183 x 91 cm) resting on another granite base. The second bronze is an allegorist female figure sitting on a globe with her legs stretched out behind her. She points her proper left arm straight in front of her while her proper right arm is raised and bent at the elbow. She is naked with a small piece of drapery on her lap.[2][11]

Inscriptions

[edit]The base housing the Marconi bust features the following inscriptions:[11]

(front)

- MARCONI

- 1874–1937.

(rear base)

- ERECTED BY POPULAR SUBSCRIPTION

- AND PRESENTED TO THE CITY OF WASHINGTON

- THE MARCONI MEMORIAL FOUNDATION

- 1940

(right side)

- Attilio Piccirilli 1940.

-

Front

-

Detail

-

Back

-

Bust detail

See also

[edit]- List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 1

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Washington, D.C.

- Outdoor sculpture in Washington, D.C.

References

[edit]- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Barsoum, Eve L. (October 2006). "National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form - Guglielmo Marconi Memorial" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Goode, James M. (1974). The Outdoor Sculpture of Washington, D.C. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 424.

- ^ "Radio falls silent for death of Marconi". The Guardian. July 20, 1937. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ a b The Commission of Fine Arts: Thirteenth Report. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1940. pp. 53–56.

- ^ "Benefit Concert To Be Given at Raleigh Hotel". The Evening Star. February 20, 1938. pp. F-6. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Marconi Memorial on Sixteenth Street is Given Approval". The Evening Star. March 14, 1941. p. 16. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ a b "Gugliemo Marconi, (sculpture)". Smithsonian Institution Archives of American Art. Archived from the original on October 11, 2023. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ United States Statutes at Large: Volume 52. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1938. p. 217.

- ^ "Washington to Get Marconi Monument". The New York Times. March 13, 1941. p. 44. ProQuest 106158731. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Marconi Memorial". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Considers Marcomi Memorial". The Evening Star. September 11, 1940. pp. A-2. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Unity Stressed at Dinner Meeting of Marconi Foundation". The Evening Star. July 23, 1941. p. 4. Archived from the original on January 27, 2024. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Kelly, John (October 1, 2016). "Why is there a memorial to Marconi, the father of radio, on 16th Street NW?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ DeFerrari, John; Sefton, Douglas Peter (2022). Sixteenth Street NW: Washington, DC's Avenue of Ambitions. Georgetown University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9781647121563.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites" (PDF). District of Columbia Office of Planning - Historic Preservation Office. September 30, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

- ^ "Marconi Memorial Cultural Landscape". National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 26, 2024. Retrieved January 26, 2024.

External links

[edit] Media related to Marconi memorial Mount Pleasant at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Marconi memorial Mount Pleasant at Wikimedia Commons

- 1941 sculptures

- Allegorical sculptures in Washington, D.C.

- Artworks in the collection of the National Park Service

- Bronze sculptures in Washington, D.C.

- Busts in Washington, D.C.

- District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites

- Guglielmo Marconi

- Granite sculptures in Washington, D.C.

- Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register in Washington, D.C.

- Monuments and memorials on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington, D.C.

- Mount Pleasant (Washington, D.C.)

- Rock Creek Park

- Sculptures of men in Washington, D.C.

- Sculptures of women in Washington, D.C.