Group velocity

The group velocity of a wave is the velocity with which the overall envelope shape of the wave's amplitudes—known as the modulation or envelope of the wave—propagates through space.

For example, if a stone is thrown into the middle of a very still pond, a circular pattern of waves with a quiescent center appears in the water, also known as a capillary wave. The expanding ring of waves is the wave group or wave packet, within which one can discern individual waves that travel faster than the group as a whole. The amplitudes of the individual waves grow as they emerge from the trailing edge of the group and diminish as they approach the leading edge of the group.

History

[edit]The idea of a group velocity distinct from a wave's phase velocity was first proposed by W.R. Hamilton in 1839, and the first full treatment was by Rayleigh in his "Theory of Sound" in 1877.[2]

Definition and interpretation

[edit]

The group velocity vg is defined by the equation:[3][4][5][6]

where ω is the wave's angular frequency (usually expressed in radians per second), and k is the angular wavenumber (usually expressed in radians per meter). The phase velocity is: vp = ω/k.

The function ω(k), which gives ω as a function of k, is known as the dispersion relation.

- If ω is directly proportional to k, then the group velocity is exactly equal to the phase velocity. A wave of any shape will travel undistorted at this velocity.

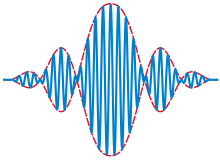

- If ω is a linear function of k, but not directly proportional (ω = ak + b), then the group velocity and phase velocity are different. The envelope of a wave packet (see figure on right) will travel at the group velocity, while the individual peaks and troughs within the envelope will move at the phase velocity.

- If ω is not a linear function of k, the envelope of a wave packet will become distorted as it travels. Since a wave packet contains a range of different frequencies (and hence different values of k), the group velocity ∂ω/∂k will be different for different values of k. Therefore, the envelope does not move at a single velocity, but its wavenumber components (k) move at different velocities, distorting the envelope. If the wavepacket has a narrow range of frequencies, and ω(k) is approximately linear over that narrow range, the pulse distortion will be small, in relation to the small nonlinearity. See further discussion below. For example, for deep water gravity waves, , and hence vg = vp /2. This underlies the Kelvin wake pattern for the bow wave of all ships and swimming objects. Regardless of how fast they are moving, as long as their velocity is constant, on each side the wake forms an angle of 19.47° = arcsin(1/3) with the line of travel.[7]

Derivation

[edit]One derivation of the formula for group velocity is as follows.[8][9]

Consider a wave packet as a function of position x and time t: α(x,t).

Let A(k) be its Fourier transform at time t = 0,

By the superposition principle, the wavepacket at any time t is

where ω is implicitly a function of k.

Assume that the wave packet α is almost monochromatic, so that A(k) is sharply peaked around a central wavenumber k0.

Then, linearization gives

where

- and

(see next section for discussion of this step). Then, after some algebra,

There are two factors in this expression. The first factor, , describes a perfect monochromatic wave with wavevector k0, with peaks and troughs moving at the phase velocity within the envelope of the wavepacket.

The other factor,

- ,

gives the envelope of the wavepacket. This envelope function depends on position and time only through the combination .

Therefore, the envelope of the wavepacket travels at velocity

which explains the group velocity formula.

Other expressions

[edit]For light, the refractive index n, vacuum wavelength λ0, and wavelength in the medium λ, are related by

with vp = ω/k the phase velocity.

The group velocity, therefore, can be calculated by any of the following formulas,

Dispersion

[edit]

Part of the previous derivation is the Taylor series approximation that:

If the wavepacket has a relatively large frequency spread, or if the dispersion ω(k) has sharp variations (such as due to a resonance), or if the packet travels over very long distances, this assumption is not valid, and higher-order terms in the Taylor expansion become important.

As a result, the envelope of the wave packet not only moves, but also distorts, in a manner that can be described by the material's group velocity dispersion. Loosely speaking, different frequency-components of the wavepacket travel at different speeds, with the faster components moving towards the front of the wavepacket and the slower moving towards the back. Eventually, the wave packet gets stretched out. This is an important effect in the propagation of signals through optical fibers and in the design of high-power, short-pulse lasers.

Relation to phase velocity, refractive index and transmission speed

[edit]

The group velocity of a collection of waves is defined as

When multiple sinusoidal waves are propagating together, the resultant superposition of the waves can result in an "envelope" wave as well as a "carrier" wave that lies inside the envelope. This commonly appears in wireless communication when modulation (a change in amplitude and/or phase) is employed to send data. To gain some intuition for this definition, we consider a superposition of (cosine) waves f(x, t) with their respective angular frequencies and wavevectors.

So, we have a product of two waves: an envelope wave formed by f1 and a carrier wave formed by f2 . We call the velocity of the envelope wave the group velocity. We see that the phase velocity of f1 is

In the context of electromagnetics and optics, the frequency is some function ω(k) of the wave number, so in general, the phase velocity and the group velocity depend on specific medium and frequency. The ratio between the speed of light c and the phase velocity vp is known as the refractive index, n = c / vp = ck / ω.

In this way, we can obtain another form for group velocity for electromagnetics. Writing n = n(ω), a quick way to derive this form is to observe

We can then rearrange the above to obtain

In three dimensions

[edit]For waves traveling through three dimensions, such as light waves, sound waves, and matter waves, the formulas for phase and group velocity are generalized in a straightforward way:[10]

- One dimension:

- Three dimensions:

where means the gradient of the angular frequency ω as a function of the wave vector , and is the unit vector in direction k.

If the waves are propagating through an anisotropic (i.e., not rotationally symmetric) medium, for example a crystal, then the phase velocity vector and group velocity vector may point in different directions.

In lossy or gainful media

[edit]The group velocity is often thought of as the velocity at which energy or information is conveyed along a wave. In most cases this is accurate, and the group velocity can be thought of as the signal velocity of the waveform. However, if the wave is travelling through an absorptive or gainful medium, this does not always hold. In these cases the group velocity may not be a well-defined quantity, or may not be a meaningful quantity.

In his text "Wave Propagation in Periodic Structures",[11] Brillouin argued that in a lossy medium the group velocity ceases to have a clear physical meaning. An example concerning the transmission of electromagnetic waves through an atomic gas is given by Loudon.[12] Another example is mechanical waves in the solar photosphere: The waves are damped (by radiative heat flow from the peaks to the troughs), and related to that, the energy velocity is often substantially lower than the waves' group velocity.[13]

Despite this ambiguity, a common way to extend the concept of group velocity to complex media is to consider spatially damped plane wave solutions inside the medium, which are characterized by a complex-valued wavevector. Then, the imaginary part of the wavevector is arbitrarily discarded and the usual formula for group velocity is applied to the real part of wavevector, i.e.,

Or, equivalently, in terms of the real part of complex refractive index, n = n + iκ, one has[14]

It can be shown that this generalization of group velocity continues to be related to the apparent speed of the peak of a wavepacket.[15] The above definition is not universal, however: alternatively one may consider the time damping of standing waves (real k, complex ω), or, allow group velocity to be a complex-valued quantity.[16][17] Different considerations yield distinct velocities, yet all definitions agree for the case of a lossless, gainless medium.

The above generalization of group velocity for complex media can behave strangely, and the example of anomalous dispersion serves as a good illustration. At the edges of a region of anomalous dispersion, becomes infinite (surpassing even the speed of light in vacuum), and may easily become negative (its sign opposes Rek) inside the band of anomalous dispersion.[18][19][20]

Superluminal group velocities

[edit]Since the 1980s, various experiments have verified that it is possible for the group velocity (as defined above) of laser light pulses sent through lossy materials, or gainful materials, to significantly exceed the speed of light in vacuum c. The peaks of wavepackets were also seen to move faster than c.

In all these cases, however, there is no possibility that signals could be carried faster than the speed of light in vacuum, since the high value of vg does not help to speed up the true motion of the sharp wavefront that would occur at the start of any real signal. Essentially the seemingly superluminal transmission is an artifact of the narrow band approximation used above to define group velocity and happens because of resonance phenomena in the intervening medium. In a wide band analysis it is seen that the apparently paradoxical speed of propagation of the signal envelope is actually the result of local interference of a wider band of frequencies over many cycles, all of which propagate perfectly causally and at phase velocity. The result is akin to the fact that shadows can travel faster than light, even if the light causing them always propagates at light speed; since the phenomenon being measured is only loosely connected with causality, it does not necessarily respect the rules of causal propagation, even if it under normal circumstances does so and leads to a common intuition.[14][18][19][21][22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Nemirovsky, Jonathan; Rechtsman, Mikael C; Segev, Mordechai (9 April 2012). "Negative radiation pressure and negative effective refractive index via dielectric birefringence". Optics Express. 20 (8): 8907–8914. Bibcode:2012OExpr..20.8907N. doi:10.1364/OE.20.008907. PMID 22513601.

- ^ Brillouin, Léon (1960), Wave Propagation and Group Velocity, New York: Academic Press Inc., OCLC 537250

- ^ Brillouin, Léon (2003) [1946], Wave Propagation in Periodic Structures: Electric Filters and Crystal Lattices, Dover, p. 75, ISBN 978-0-486-49556-9

- ^ Lighthill, James (2001) [1978], Waves in fluids, Cambridge University Press, p. 242, ISBN 978-0-521-01045-0

- ^ Lighthill (1965)

- ^ Hayes (1973)

- ^ G.B. Whitham (1974). Linear and Nonlinear Waves (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1974) pp 409–410 Online scan

- ^ Griffiths, David J. (1995). Introduction to Quantum Mechanics. Prentice Hall. p. 48. ISBN 9780131244054.

- ^ David K. Ferry (2001). Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction for Device Physicists and Electrical Engineers (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 18–19. Bibcode:2001qmid.book.....F. ISBN 978-0-7503-0725-3.

- ^ Atmospheric and oceanic fluid dynamics: fundamentals and large-scale circulation, by Geoffrey K. Vallis, p239

- ^ Brillouin, L. (1946). Wave Propagation in Periodic Structures. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 75.

- ^ Loudon, R. (1973). The Quantum Theory of Light. Oxford.

- ^ Worrall, G. (2012). "On the Effect of Radiative Relaxation on the Flux of Mechanical-Wave Energy in the Solar Atmosphere". Solar Physics. 279 (1): 43–52. Bibcode:2012SoPh..279...43W. doi:10.1007/s11207-012-9982-z. S2CID 119595058.

- ^ a b Boyd, R. W.; Gauthier, D. J. (2009). "Controlling the velocity of light pulses" (PDF). Science. 326 (5956): 1074–7. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1074B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.630.2223. doi:10.1126/science.1170885. PMID 19965419. S2CID 2370109.

- ^ Morin, David (2009). "Dispersion" (PDF). people.fas.harvard.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-05-21. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- ^ Muschietti, L.; Dum, C. T. (1993). "Real group velocity in a medium with dissipation". Physics of Fluids B: Plasma Physics. 5 (5): 1383. Bibcode:1993PhFlB...5.1383M. doi:10.1063/1.860877.

- ^ Gerasik, Vladimir; Stastna, Marek (2010). "Complex group velocity and energy transport in absorbing media". Physical Review E. 81 (5): 056602. Bibcode:2010PhRvE..81e6602G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.81.056602. PMID 20866345.

- ^ a b Dolling, Gunnar; Enkrich, Christian; Wegener, Martin; Soukoulis, Costas M.; Linden, Stefan (2006), "Simultaneous Negative Phase and Group Velocity of Light in a Metamaterial", Science, 312 (5775): 892–894, Bibcode:2006Sci...312..892D, doi:10.1126/science.1126021, PMID 16690860, S2CID 29012046

- ^ a b Bigelow, Matthew S.; Lepeshkin, Nick N.; Shin, Heedeuk; Boyd, Robert W. (2006), "Propagation of a smooth and discontinuous pulses through materials with very large or very small group velocities", Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter, 18 (11): 3117–3126, Bibcode:2006JPCM...18.3117B, doi:10.1088/0953-8984/18/11/017, S2CID 38556364

- ^ Withayachumnankul, W.; Fischer, B. M.; Ferguson, B.; Davis, B. R.; Abbott, D. (2010), "A Systemized View of Superluminal Wave Propagation", Proceedings of the IEEE, 98 (10): 1775–1786, doi:10.1109/JPROC.2010.2052910, S2CID 15100571

- ^ Gehring, George M.; Schweinsberg, Aaron; Barsi, Christopher; Kostinski, Natalie; Boyd, Robert W. (2006), "Observation of a Backward Pulse Propagation Through a Medium with a Negative Group Velocity", Science, 312 (5775): 895–897, Bibcode:2006Sci...312..895G, doi:10.1126/science.1124524, PMID 16690861, S2CID 28800603

- ^ Schweinsberg, A.; Lepeshkin, N. N.; Bigelow, M.S.; Boyd, R. W.; Jarabo, S. (2005), "Observation of superluminal and slow light propagation in erbium-doped optical fiber" (PDF), Europhysics Letters, 73 (2): 218–224, Bibcode:2006EL.....73..218S, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.205.5564, doi:10.1209/epl/i2005-10371-0, S2CID 250852270[permanent dead link]

Further reading

[edit]- Crawford jr., Frank S. (1968). Waves (Berkeley Physics Course, Vol. 3), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0070048607 Free online version

- Tipler, Paul A.; Llewellyn, Ralph A. (2003), Modern Physics (4th ed.), New York: W. H. Freeman and Company, p. 223, ISBN 978-0-7167-4345-3.

- Biot, M. A. (1957), "General theorems on the equivalence of group velocity and energy transport", Physical Review, 105 (4): 1129–1137, Bibcode:1957PhRv..105.1129B, doi:10.1103/PhysRev.105.1129

- Whitham, G. B. (1961), "Group velocity and energy propagation for three-dimensional waves", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, 14 (3): 675–691, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.205.7999, doi:10.1002/cpa.3160140337

- Lighthill, M. J. (1965), "Group velocity", IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics, 1 (1): 1–28, doi:10.1093/imamat/1.1.1

- Bretherton, F. P.; Garrett, C. J. R. (1968), "Wavetrains in inhomogeneous moving media", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 302 (1471): 529–554, Bibcode:1968RSPSA.302..529B, doi:10.1098/rspa.1968.0034, S2CID 202575349

- Hayes, W. D. (1973), "Group velocity and nonlinear dispersive wave propagation", Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 332 (1589): 199–221, Bibcode:1973RSPSA.332..199H, doi:10.1098/rspa.1973.0021, S2CID 121521673

- Whitham, G. B. (1974), Linear and nonlinear waves, Wiley, ISBN 978-0471940906

External links

[edit]- Greg Egan has an excellent Java applet on his web site that illustrates the apparent difference in group velocity from phase velocity.

- Maarten Ambaum has a webpage with movie Archived 2019-05-04 at the Wayback Machine demonstrating the importance of group velocity to downstream development of weather systems.

- Phase vs. Group Velocity – Various Phase- and Group-velocity relations (animation)