Bartholin's gland

| Bartholin's gland | |

|---|---|

Female genital organs with Bartholin's gland opening circled | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Urogenital sinus |

| Artery | External pudendal artery[1] |

| Nerve | Ilioinguinal nerve[1] |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula vestibularis major |

| MeSH | D001472 |

| TA98 | A09.2.01.016 |

| TA2 | 3563 |

| FMA | 9598 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The Bartholin's glands (named after Caspar Bartholin the Younger; also called Bartholin glands or greater vestibular glands) are two pea-sized compound alveolar glands[2] located slightly posterior and to the left and right of the opening of the vagina.[3] They secrete mucus to lubricate the vagina.[3]

They are homologous to bulbourethral glands in males. However, while Bartholin's glands are located in the superficial perineal pouch in females, bulbourethral glands are located in the deep perineal pouch in males. Their duct length is 1.5 to 2.0 cm and they open into navicular fossa.[2] The ducts are paired and they open on the surface of the vulva.[3]

Structure

[edit]The embryological origin of the Bartholin's glands is derived from the urogenital sinus; therefore, the innervation and blood supply are via the pudendal nerve and external pudendal artery, respectively. The superficial inguinal lymph nodes and pelvic nodes provide lymphatic drainage.[4]

These glands are pea-sized (0.5–1.0 cm) and are lined with columnar epithelium. The duct length is 1.5–2 cm and is lined with squamous epithelium. These are located just beneath the fascia and their ducts drain into the vestibular mucosa. These mucoid alkaline secreting glands are arranged as lobules consisting of alveoli lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelium. Their efferent ducts are composed of transitional epithelium, which merges into squamous epithelium as it enters the distal vagina. The more proximal portions of the ductal system are lined by transitional epithelium and may be lined by columnar epithelium before arborization into glandular secretory elements.[5]

These glands lie on the perineal membrane and beneath the bulbospongiosus muscle at the tail end of the vestibular bulb deep to the posterior labia majora. The intimate relation between the enormously vascular tissue of the vestibular bulb and the Bartholin's glands is responsible for the risk of hemorrhage associated with the removal of this latter structure.[6]

The openings of the Bartholin's glands are located on the posterior margin of the introitus bilaterally in a groove between the hymen and the labium minus at the 4:00 and 8:00 o'clock positions. The glands duct opening is seen on the posterolateral aspect of the vestibule 3 to 4 mm outside the hymen or hymenal caruncles lateral to the hymenal ring.[7]

History

[edit]

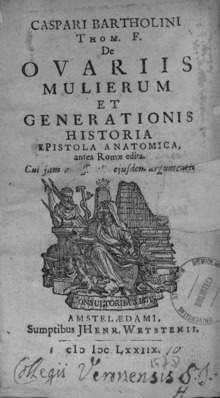

Bartholin's glands were first described in 1677 by the 17th-century Danish anatomist Caspar Bartholin the Younger (1655–1738).[8][9] Earlier he jointly discovered the glands in cows with Joseph Guichard Duverney (1648-1730), a French anatomist.[10] Some sources mistakenly ascribe their discovery to his grandfather, theologian and anatomist Caspar Bartholin the Elder (1585–1629).[11]

Function

[edit]Bartholin's glands secrete mucus to provide vaginal lubrication during sexual arousal.[9][12][13] The fluid may slightly moisten the labial opening of the vagina, serving to make contact with this sensitive area more comfortable.[14] Fluid from the Bartholin's glands is combined with other vaginal secretions as a "lubrication fluid" in the amount of about 6 grams per day, and contains high potassium and low sodium concentrations relative to blood plasma, with a slightly acidic pH of 4.7.[15]

Clinical pathology

[edit]It is possible for the Bartholin's glands to become blocked and inflamed resulting in pain.[14] This is known as bartholinitis or a Bartholin's cyst.[9][16][17] A Bartholin's cyst in turn can become infected and form an abscess. Adenocarcinoma of the gland is rare and benign tumors and hyperplasia are even more rare.[18] Bartholin gland carcinoma[19] is a rare malignancy that occurs in 1% of vulvar cancers. This may be due to the presence of three different types of epithelial tissue.[8] Inflammation of the Skene's glands and Bartholin glands may appear similar to cystocele.[20]

Other animals

[edit]The major vestibular glands are found in many mammals such as cats, cows, and some sheep.[21][22]

See also

[edit]- List of distinct cell types in the adult human body

- List of related male and female reproductive organs

- Mesonephric duct

- Skene's gland

References

[edit]- ^ a b Greater Vestibular (Bartholin) gland Archived January 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier. pp. 1-16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ a b c Broach, Vance; Lawson, Barrett (2023). "Bartholin gland carcinomas". Diagnosis and Treatment of Rare Gynecologic Cancers. pp. 305–314. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-82938-0.00018-5. ISBN 978-0-323-82938-0.

- ^ Omole F, Simmons BJ, Hacker Y. Management of Bartholin's duct cyst and gland abscess. Am Fam Physician 2003;68:135–40.

- ^ Quaresma C, Sparzak PB. Anatomy, abdomen and pelvis, Bartholin gland. StatPearls. [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan 24.

- ^ DeLancey JO. Surgical anatomy of the female pelvis. In: Jones HW, Rock JA, eds. Te Linde’s Operative Gynecology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:93-122.

- ^ Hoffman B.L., Schorge J.O., Schaffer J.I., Halvorson L.M., Bradshaw K.D., Cunnigham F.G., Calver L.E. (2012). Chapter 38. Anatomy. In B.L. Hoffman, J.O. Schorge, J.I. Schaffer, L.M. Halvorson, K.D. Bradshaw, F.G. Cunnigham, L.E. Calver (Eds), Williams Gynecology, 2e.

- ^ a b Heller, Debra S.; Bean, Sarah (2014). "Lesions of the Bartholin Gland". Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 18 (4): 351–357. doi:10.1097/LGT.0000000000000016. ISSN 1089-2591. PMID 24914884.

- ^ a b c Lee, Min Y.; Dalpiaz, Amanda; Schwamb, Richard; Miao, Yimei; Waltzer, Wayne; Khan, Ali (May 2015). "Clinical Pathology of Bartholin's Glands: A Review of the Literature". Current Urology. 8 (1): 22–25. doi:10.1159/000365683. PMC 4483306. PMID 26195958.

- ^ Benkhadra M, Salomon C, Bressanutti V, Cheynel N, Genelot D, Trost O, Trouilloud P. [Joseph-Guichard Duverney (1648-1730). Doctor, teacher and researcher in the 17th and 18th centuries]. (2010) Morphologie : bulletin de l'Association des anatomistes. 94 (306): 63-7. doi:10.1016/j.morpho.2010.02.001 - Pubmed

- ^ C. C. Gillispie (ed.): Dictionary of Scientific Biography, New York 1970.[page needed].

- ^ "Viscera of the Urogenital Triangle". University of Arkansas Medical School. Archived from the original on 2010-07-15. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ Chrétien, F.C.; Berthou J. (September 18, 2006). "Crystallographic investigation of the dried exudate of the major vestibular (Bartholin's) glands in women". Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 135 (1): 116–22. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.06.031. PMID 16987591.

- ^ a b "Bartholin's Gland". Discovery Health. Archived from the original on 2008-08-04.

- ^ Pastor, Zlatko; Chmel, Roman (May 2018). "Differential diagnostics of female 'sexual' fluids: a narrative review". International Urogynecology Journal. 29 (5): 621–629. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3527-9. PMID 29285596. S2CID 5045626.

- ^ Sue E. Huether (2014). Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults and Children. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 817. ISBN 9780323293754.

- ^ Lee, William A.; Wittler, Micah (2022). "Bartholin Gland Cyst". StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. PMID 30335304.

- ^ Argenta PA, Bell K, Reynolds C, Weinstein R (Oct 1997). "Bartholin's gland hyperplasia in a postmenopausal woman". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 90 (4 part 2): 695–7. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00409-2. PMID 11770602. S2CID 8403143.

- ^ Bora, Shabana A.; Condous, George (October 2009). "Bartholin's, vulval and perineal abscesses". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 23 (5): 661–666. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2009.05.002. PMID 19647493.

- ^ "Cystoceles, Urethroceles, Enteroceles, and Rectoceles - Gynecology and Obstetrics - Merck Manuals Professional Edition". Merck Manuals Professional Edition. Retrieved 2018-02-06.

- ^ Leibich, Hans-Georg (2019). Veterinary Histology of Domestic Mammals and Birds: Textbook and Colour Atlas. 5m Publishing Limited. pp. 14–30. ISBN 978-1-78918-106-7.

- ^ McEntee, Mark (2012). Reproductive Pathology of Domestic Mammals. Elsevier Science. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-32313-804-8.