Key of Solomon

The Key of Solomon (Latin: Clavicula Salomonis; Hebrew: מַפְתֵּחַ-שְׁלֹמֹה, romanized: Map̄teḥ Šəlomo), also known as the Greater Key of Solomon, is a pseudepigraphical grimoire attributed to King Solomon. It probably dates back to the 14th or 15th century Italian Renaissance. It presents a typical example of Renaissance magic.[citation needed]

It is possible that the Key of Solomon inspired later works, particularly the 17th-century grimoire also known as The Lesser Key of Solomon or Lemegeton, although there are many differences between the books.[citation needed]

Manuscripts and textual history

[edit]Many such grimoires attributed to King Solomon were written during the Renaissance, ultimately being influenced by earlier works of Jewish theosophical kabbala and Muslim magicians.[1] These, in turn, incorporated aspects of the Greco-Roman magic of late antiquity.[2]

Several versions of the Key of Solomon exist, in various translations, with minor to significant differences. The original type of text was probably a Latin or Italian text dating to the 14th or 15th century.[3] Most surviving manuscripts date from the late 16th, 17th or 18th century. There is also an early Greek manuscript dating to the 15th century (British Library, Harley MS 5596) that is closely associated with the text.[citation needed] The Greek manuscript is referred to as The Magical Treatise of Solomon, and was published by Armand Delatte in Anecdota Atheniensia (Liège, 1927, pp. 397–445.) Its contents are very similar to the Clavicula.

An important Italian manuscript is (Bodleian Library, Michael MS 276) an early Latin text survives in printed form, dated to ca. 1600 (University of Wisconsin-Madison, Memorial Library, Special Collections). There are a number of later (17th century) Latin manuscripts. One of the oldest existing manuscripts (besides Harley MS 5596) is a text in English translation, entitled The Clavicle of Solomon, revealed by Ptolomy the Grecian and dated to 1572 (British Library, Sloane MS 3847). There are a number of French manuscripts, all dated to the 18th century, with the exception of one dated to 1641 (P1641, ed. Dumas, 1980).

A Hebrew text survives in two versions, one kept at the British Library, on a parchment manuscript, separated in BL Oriental MSS 6360 and 14759. The BL manuscript was dated to the 16th century by its first editor Greenup (1912), but is now thought to be somewhat younger, dating to the 17th or 18th century.[4] The discovery of a second Hebrew text in the library of Samuel H. Gollancz was published by his son Hermann Gollancz in 1903, who also published a facsimile edition in 1914.[5] Gollancz's manuscript had been copied in Amsterdam, in the Sephardic cursive Solitreo script, and is less legible than the BL text. The Hebrew text is not considered the original. It is rather a late Jewish adaptation of a Latin or Italian Clavicula text. The BL manuscript is probably the archetype of the Hebrew translation, and Gollancz's manuscript a copy of the BL one.[4]

A French edition titled La véritable Magie Noire ou Le secret des secrets (The True Black Magic or The secret of secrets) is kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. It is a translation from Hebrew by Iroé-Grego, dated 1750.[6]

An English edition based on the manuscripts of the British Library was published by S. L. MacGregor Mathers in 1889.[7] L. W. de Laurence in 1914 published The Greater Key of Solomon, directly based on Mathers' edition, to which he made alterations in an attempt to advertise his mail-order business (for example by inserting instructions like "after burning one-half teaspoonful of Temple Incense" along with ordering information for the incense).

Contents

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2009) |

Summary

[edit]The Key of Solomon is divided into two books. It describes the necessary drawings to prepare each "experiment" or, in more modern language, magical operations.

Unlike later grimoires such as the Pseudomonarchia Daemonum (16th century) or the Lemegeton (17th century), the Key of Solomon does not mention the signature of the 72 spirits constrained by King Solomon in a bronze vessel. As in most medieval grimoires, all magical operations are ostensibly performed through the power of God, to whom all the invocations are addressed. Before any of these operations (termed "experiments"), the operator must confess his sins and purge himself of evil, invoking the protection of God.

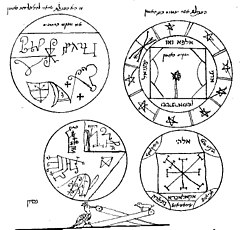

Elaborate preparations are necessary, and each of the numerous items used in the operator's "experiments" must be constructed of the appropriate materials obtained in the prescribed manner, at the appropriate astrological time, marked with a specific set of magical symbols, and blessed with its own specific words. All substances needed for the magic drawings and amulets are detailed, as well as the means to purify and prepare them. Many of the symbols incorporate the Transitus Fluvii occult alphabet.

Introduction

[edit]According to the mythical history of the document, as recorded in its introduction, Solomon wrote the book for his son Rehoboam, and commanded him to hide the book in his sepulchre upon his death. After many years the book was discovered by a group of Babylonian philosophers repairing Solomon's tomb. None could interpret the text, until one of them, Iohé Grevis, suggested that they should ask the Lord for understanding. The Angel of the Lord appeared to him and extracted a promise that he would keep the text hidden from the unworthy and the wicked, after which he was able to read it plainly. Iohé Grevis then placed a spell on the book that the unworthy, the unwise or those who did not fear God would not attain the desired effect from any of the workings contained in the book.

Book I

[edit]Book I contains conjurations, invocations, and curses to summon and constrain spirits of the dead and demons in order to compel them to do the operator's will. It also describes how to find stolen items, become invisible, gain favour and love, and so on.

Book II

[edit]Book II describes various purifications which the operator (termed "exorcist") should undergo, how they should clothe themselves, how the magical implements used in their operations should be constructed, and what animal sacrifices should be made to the spirits.

Cultural references

[edit]The book is mentioned in Goethe’s Faust I, in the scene where the poodle transforms himself into the devil Mephistopheles.[8]

For such as your half-hellish crew – The Key of Solomon will do.

The Key of Solomon is mentioned in H.P. Lovecraft's "Supernatural Horror in Literature", where Lovecraft says it "illustrates the power of the weird over the Eastern mind".

Along with Johannes Kepler’s Astronomia Nova, the Key of Solomon is one of two real-world texts the fictional character Dr. Stephen Strange returns to the Kamar-Taj library in the Marvel Studios film Doctor Strange. In the scene, Kamar-Taj Librarian and current Marvel Cinematic Universe Sorcerer Supreme Wong reads the titles Strange is returning. [9]

“The Book of the Invisible Sun, Astronomia Nova, Codex Imperium, Key of Solomon. You finished all of these?”

English translations

[edit]- The Key of Solomon the King (Clavicula Salomonis). Trans. and ed. S. Liddell MacGregor Mathers [1889]. Foreword by R. A. Gilbert. Boston/York Beach, ME: Weiser Books, 2000.

- The Veritable Key of Solomon. Translated by Stephen Skinner and David Rankine, Llewellyn Publications, 2008.

See also

[edit]- Black magic

- Incantation

- White magic

- Gray magic

- Magical Treatise of Solomon

- Mediumship

- Mysticism

- Renaissance magic

- Testament of Solomon

- Talisman

- Sacred Heart

- Worship of heavenly bodies

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lelli, Fabrizio (December 2007). "Hermes Among the Jews: Hermetica as Hebraica from Antiquity to the Renaissance". Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft. 2 (2): 111–135. doi:10.1353/mrw.0.0006.

- ^ Bremmer, Jan N.; Veenstra, Jan R. (2002). The Metamorphosis of Magic from Late Antiquity to the Early Modern Period. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-429-1227-4.

- ^ "there is no ground for attributing the Key of Solomon, in its present form, a higher antiquity than the fourteenth or fifteenth century." Arthur Edward Waite The Book of Black Magic p. 70

- ^ a b Rohrbacher-Sticker, Jewish Studies quarterly, Volume 1, 1993/94 No. 3, with a follow-up article in the British Library Journal, Volume 21, 1995, p. 128–136.

- ^ A more recent facsimile edition of this book, Sepher Maphteah Shelomoh (Book of the Key of Solomon)(2008), was published by Teitan Press in 2008. Introductions by Hermann Gollancz and a Foreword by Stephen Skinner.

- ^ Grego, Iroé (1750). La véritable magie noire ou Le secret des secrets. Manuscrit trouvé à Jerusalem, dans le sépulcre de Salomon. Contenant : 1. ° Quarante-cinq talismans avec leurs gravures, ainsi que la manière de s'en servir, et leurs merveilleuses propriétés ; 2.° Tous les caractères magiques connus jusqu'à ce jour, traduit de l'hébreu, du mage Iroé-Grego.

- ^ Mathers, S. L. MacGregor (1889). The Key of Solomon the King. London: George Redway.

- ^ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust I (1808), Translated by A. S. Kline (2003), lines 1257–1258, https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/German/Fausthome.php

- ^ Marvel’s Doctor Strange, 2016, 36:14

References

[edit]- Elizabeth Butler, Ritual Magic, ISBN 0-271-01846-1, part II, chapter 1, "The Solomonic Cycle", pp. 47–99.

- Arthur E. Waite, The Book of Black Magic, ISBN 0-87728-207-2, Chapter 2, "Composite Rituals", pp. 52

External links

[edit]- S. L. Mathers' version of Key of Solomon at Esoteric Archives

- Key of Knowledge, two older English versions of Key of Solomon, at Esoteric Archives

- Are King Solomon’s Magical Powers Concealed Inside This Book? Article on pseudepigraphy using the Key of Solomon as an example, by Chen Malul, at the National Library of Israel.