Frisia

Frisia | |

|---|---|

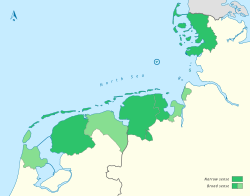

Location of Frisia in the northern Netherlands and northwestern Germany | |

| Largest city | Leeuwarden |

| Regional languages | |

Dialects | |

| Demonym(s) | Frisian |

| Integrated parts of Germany and the Netherlands with varying degrees of autonomy | |

| Area | |

• Narrow sense | 9,378.7 km2 (3,621.1 sq mi) |

• Broad sense | 13,482.7 km2 (5,205.7 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Narrow sense | 1,475,380 (in 2,020) |

• Broad sense | 2,678,792 (in 2,020) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Frisia[a] is a cross-border cultural region in Northwestern Europe. Stretching along the Wadden Sea, it encompasses the north of the Netherlands and parts of northwestern Germany. Wider definitions of "Frisia" may include the island of Rem and the other Danish Wadden Sea Islands. The region is traditionally inhabited by the Frisians, a West Germanic ethnic group.

Etymology

[edit]The contemporary name for the region stems from Latin Frisii, an ethnonym used for a group of ancient tribes in modern-day Northwestern Germany, possibly being a loanword of Proto-Germanic *frisaz, meaning "curly, crisp", presumably referring to the hair of the tribesmen. In some areas, the local translation of "Frisia" is used to refer to another subregion. On the North Frisian islands, for instance, "Frisia" and "Frisians" refer to (the inhabitants of) mainland North Frisia. In Saterland Frisian, the term Fräislound specifically refers to Ostfriesland.[1]

During the French occupation of the Netherlands, the name for the Frisian department was Frise. In English, both "Frisia" and "Friesland" may be interchangeably used to refer to the region.

Subdivisions

[edit]Frisia is commonly divided into three sections:

- West Frisia in the Netherlands roughly corresponds to the province of Friesland (Fryslân). In a broader sense, it also includes West Friesland in northern North Holland and the Ommelanden in the province of Groningen, though the West Frisian language is only spoken in Friesland proper. Dialects with strong West Frisian substrates, including Low German and Low Franconian, are also spoken in West Frisia. In the province of Groningen, people speak Gronings, a Low Saxon dialect with a strong Frisian substrate. Rural Groningen originally belonged to the Frisian lands "east of the Lauwers" and is therefore more closely linked to East Frisia than to the west. In West Friesland, West Frisian Dutch – a Hollandic dialect with strong Frisian influences – is spoken.

- East Frisia in Lower Saxony, Germany roughly corresponds to the historical regions of East Frisia (Aurich, Leer, Wittmund and Emden) and Oldenburger Friesland (Friesland and Wilhelmshaven), and the municipality of Saterland. In a broader sense, it also includes the Butjadingen peninsula (former Rüstringen) and Land Wursten. Usually, only the people from East Frisia proper (German: Ostfriesland) refer to themselves as East Frisians. The German name Ostfriesland distinguishes the historical region from Ost-Friesland, which refers to East Frisia as a whole.

- North Frisia in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany roughly corresponds to the district of Nordfriesland and the archipelago of Heligoland. It includes the North Frisian Islands, where varieties of the North Frisian language are spoken. It stretches from the Eider River in the south to the border of Denmark in the north. Until the Second Schleswig War in 1864, the region belonged to the Danish Duchy of Schleswig.

| Section | Subdivision | Flag | Population (2020) | Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Frisia | Nordfriesland | 167,147 | 2,047 km2 (790 sq mi) | |

| Heligoland | 1,307 | 1.7 km2 (0.66 sq mi) | ||

| East Frisia | Ostfriesland (Aurich, Emden, Leer, Wittmund) | 468,919 | 3,142 km2 (1,213 sq mi) | |

| Oldenburger Friesland (Friesland, Wilhelmshaven) | 174,160 | 715 km2 (276 sq mi) | ||

| Saterland | 13,903 | 124 km2 (48 sq mi) | ||

| Rüstringen (Butjadingen peninsula) | 45,538 | 423 km2 (163 sq mi) | ||

| Land Wursten | 17,101 | 182 km2 (70 sq mi) | ||

| West Frisia | Fryslân | 649,944 | 3,349 km2 (1,293 sq mi) | |

| West Friesland | 554,464 | 1,174 km2 (453 sq mi) | ||

| Ommelanden (Groningen) | 586,309 | 2,325 km2 (898 sq mi) |

History

[edit]Roman era

[edit]The people, later to be known as Frisii, began settling in Frisia in the 6th century BC. According to Pliny the Elder, in Roman times, the Frisians (or rather their close neighbours, the Chauci) lived on terps, man-made hills.[2] According to other sources, the Frisians lived along a broader expanse of the North Sea (or "Frisian Sea") coast.[b] At this time, Frisia comprised the present-day provinces of Friesland, Groningen, North Holland and parts of South Holland.[3]

Early Middle Ages

[edit]

Frisian presence during the Early Middle Ages has been documented from North-Western Flanders up to the Weser River Estuary. According to archaeological evidence, these Frisians were not the Frisians of Roman times, but the descendants of Anglo-Saxon immigrants from the German Bight, arriving during the Great Migration. By the 8th century, ethnic Frisians also started to colonize the coastal areas North of the Eider River under Danish rule. The nascent Frisian languages were spoken all along the southern North Sea coast.[4] Today, the whole region is sometimes referred to as Greater Frisia (Latin: Frisia Magna).

Distant authors seem to have made little distinction between Frisians and Saxons. The Byzantine Procopius described three peoples living in Great Britain: Angles, Frisians and Britons,[5] and the Danish author of Knútsdrápa celebrating the 11th-century Canute the Great used "Frisians" as a synonym of "English".[c] The historian and sociologist George Homans has made a case for Frisian cultural domination in East Anglia since the 5th century, pointing to distinct land-holdings arrangements in carucates (these forming vills assembled in leets), partible inheritance patterns of common lands held in by kin, resistance to manorialism and other social institutions.[6] Some East Anglian sources called the mainland inhabitants Warnii, rather than Frisians.

During the 7th and 8th centuries, Frankish chronologies mention the northern Low Countries as the kingdom of the Frisians. According to Medieval legends, this kingdom comprised the coastal seelande provinces of the Netherlands, from the Scheldt River to the Weser River and further East. Archaeological research does not confirm this idea, as the petty kingdoms appear to have been rather small and short-lived.

The earliest Frisian records name four social classes, the ethelings (nobiles in Latin documents) and frilings, who together made up the "Free Frisians" who might bring suit at court, and the laten or liten with the slaves, who were absorbed into the laten during the Early Middle Ages, as slavery was not so much formally abolished, as evaporated.[d] The laten were tenants of lands they did not own and might be tied to it in the manner of serfs, but in later times might buy their freedom.[6]: 202

The basic land-holding unit for assessment of taxes and military contributions was – according to Homans – the ploegg (cf. "plow") or teen (cf. tithing, cf. "hundred"), which, however, also passed under other local names. The teen was pledged to supply ten men for the heer, or army. Ploegg or teen formed a unit of which the members were collectively responsible for the performance of any of the men. The ploegg or East Frisian rott was a compact holding that originated with a single lineage or kinship, whose men in early times went to war under their chief, and devolved in medieval times into a union of neighbors rather than kith and kin. Several, often three, ploeggs were grouped into a burar, whose members controlled and adjudicated the uses of pasturage (but not tillage) which the ploeggs held in common, and came to be in charge of roads, ditches and dikes. Twelve ploeggs made up a "long" hundred,[e] responsible for supplying a hundred armed men, four of which made a go (cf. Gau). Homans' ideas, which were largely based on studies now considered to be outdated, have not been followed up by Continental scholars.

The 7th-century Frisian Realm (650–734) under the kings Aldegisel and Redbad, had its centre of power in the city of Utrecht. Its ancient customary law was drawn up as the Lex Frisionum in the late eighth century. Its end came in 734 at the Battle of the Boarn, when the Frisians were defeated by the Franks, who then conquered the western part up to the Lauwers. Frankish troops conquered the area east of the Lauwers in 785, after Charlemagne defeated the Saxon leader Widukind. The Carolingians laid Frisia under the rule of grewan, a title that has been loosely related to count in its early sense of "governor" rather than "feudal overlord".[6]: 205

During the 7th to 10th centuries, Frisian merchants and skippers played an important part in the international luxury trade, establishing commercial districts in distant cities as Sigtuna, Hedeby, Ribe, York, London, Duisburg, Cologne, Mainz, and Worms.

The establishment of the Frisian trade network played a significant role in maintaining regional peace during the late Middle Ages. While interpersonal violence was on the rise almost everywhere else in Europe, Northern Europe and especially Frisia managed to maintain low levels of violence due in part to its well-developed society and established rule of law, which were results of extensive trade.[7]

The Frisian coastal areas were partly occupied by Danish Vikings in the 840s, until these were expelled between 885 and 920. Recently, it has been suggested that the Vikings did not conquer Frisia, but settled peacefully in certain districts (such as the islands of Walcheren and Wieringen), where they built simple forts and cooperated and traded with the native Frisians. One of their leaders was Rorik of Dorestad.

Upstalsboom League

[edit]During the 12th century Frisian noblemen and the city of Groningen founded the Upstalsboom League under the slogan of "Frisian freedom" to counter feudalizing tendencies. The league consisted of modern Friesland, Groningen, East Frisia, Harlingerland, Jever and Rüstringen. The Frisian districts in West Friesland West of the Zuiderzee did not participate, neither did the districts North of the Eider River along the Danish North Sea coast (Schleswig-Holstein). The former were occupied by the count of Holland in 1289, and the latter were governed by the Duke of Schleswig and the king of Denmark. The same holds true for the district of Land Wursten East of the Weser River. The Upstalsboom League was revived in the early 14th century, but it collapsed after 1337. By then, the non-Frisian city of Groningen took the lead of the independent coastal districts.

15th century

[edit]

The 15th century saw the demise of Frisian republicanism. In East Frisia, a leading nobleman from the Cirksena-family managed to defeat his competitors with the help of the Hanseatic League. In 1464 he acquired the title of count of East Frisia. The king of Denmark was successful in subduing the coastal districts North of the Eider River. The Dutch provinces of Friesland and Groningen remained independent until 1498. By then Friesland was conquered by Duke Albert of Saxony-Meissen. The city of Groningen, which had started to dominate the surrounding rural districts, surrendered to count Edzard of East Frisia in 1506. The city conveyed its remaining privileges to the Habsburg Empire in 1536. The district of Butjadingen (formerly Rüstringen) was occupied by the Count of Oldenburg in 1514, the Land Wursten by the Prince-bishop of Bremen in 1525.

Modern age

[edit]In the early 16th century, the pirate and freedom fighter Pier Gerlofs Donia (Grutte Pier) challenged Saxon authority in Friesland during a prolonged guerrilla war, backed by the Duke of Guelders. He had several successes and was feared by Hollandic authorities, but he died as a farmer in 1520. According to the legend he was seven feet tall. A statue of Grutte Pier by Anne Woudwijk was erected in Kimswert in 1985.

In the 1560s many Frisans joined the revolt led by William of Orange against the Habsburg monarchy. In 1577 the province of Friesland became part of the nascent Dutch Republic, as its representatives signed the Union of Utrecht. The city of Groningen was conquered by the Dutch in 1594. Since then, membership of the Dutch Republic was perceived as a guarantee for the preservation of civil liberties. Actual power, however, was usurped by the landowning gentry. Protests against aristocratic rule led to a democratic movement in the 1780s.

Frisian territories

[edit]- When West Friesland was conquered by the County of Holland in 1289, this was the end of a series of wars between the county of Holland and Friesland that started at the end of the 11th century. The Dutch conquest occurred immediately after the disastrous St. Lucia's flood in which many Frisians in the area were killed. After the conquest the district of West Friesland, which also comprised the islands of Wieringen, Texel, and Vlieland, had its own seats in the Estates of Holland and West Friesland. When the province of Holland was split up in the constitutional reform of 1840, West-Friesland became a part of North Holland. The name of West Friesland has also been used by an intercommunal administrative board (samenwerkingsregio) and a water board.

- Friesland became an independent member of the Dutch Republic in 1581. It is now a Dutch province, in 1996 renamed as Fryslân.

- The islands of Terschelling, Ameland, and Schiermonnikoog were independent seignories, which were integrated into the province of Friesland during the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Groningen, formerly Stad en Lande (the city of Groningen and its surroundings), became an independent member of the Dutch Republic in 1594. Now it is a Dutch province. As a rule, its inhabitants do not consider their province as a part of Frisia, though the area has many cultural ties with neighbouring East Frisia.

- East Frisia was an independent county since 1464, later a principality within the Holy Roman Empire until 1744. By then, it was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia. After a period of Dutch and French rule, it became part of the Kingdom of Hanover in 1814, which was annexed by Prussia in 1866. Now it consists of several districts within the federal state of Lower Saxony in the Federal Republic of Germany.

- Harlingerland was a seignory, inherited by the count of East Frisia in 1600.

- Jever was a seignory, annexed by the County of Oldenburg in 1573 and, after a prolonged period of Saxony-Anhalt, Russian, Dutch and French rule, reunited with Oldenburg in 1814. It is now part of the district of Friesland within the federal state of Lower Saxony.

- Kniphausen was a seignory, split off from the County of Oldenburg in 1667 and reunited with its surroundings in 1854 (effectively in 1813).

- Saterland was a tiny Frisian district under the Prince-bishop of Münster, in 1814 assigned to the Kingdom of Hannover.

- Butjadingen was a coastal republic, a remnant of the largely submerged district of Rüstringen. It was conquered by the Count of Oldenburg in 1514. After a period of Danish rule, it became part of the Duchy of Oldenburg in 1774, which remained a more or less independent state within the German Empire until 1918. Butjadingen is now part of the district of Wesermarsch within the federal state of Lower Saxony.

- Land Wursten was a coastal republic, conquered by the Prince-bishop of Bremen in 1525. It became part of the Duchy of Bremen-Verden. The latter was, after a period of Swedish rule, integrated into the Kingdom of Hanover in 1715. It is now part of the district of Cuxhaven within the federal state of Lower Saxony.

- North Frisia originally corresponded to the Uthlande in the Kingdom of Denmark. Later, North Frisia became a part of the Danish Duchy of Schleswig (or Southern Jutland, Sønderjylland) and of the royal enclaves (Kongerigske enklaver) of the Kingdom of Denmark. The duchy was conquered by Prussia in 1864. Now it forms a district within the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Helgoland is part of the district of Pinneberg. North Frisia was never a part of the Holy Roman Empire.

Contemporary regionalism

[edit]During the late 19th and early 20th century, "Frisian freedom" became the slogan of a regionalist movement in Friesland, demanding equal rights for the Frisian language and culture within the Netherlands. The West Frisian language and its urban dialects are spoken by the majority of the inhabitants. In East Frisia, the idea of "Frisian freedom" became entangled with regional sentiments as well, though the East Frisian language had been replaced by Low German dialects as early as the 15th century. In Groningen, on the other hand, Frisian sentiments faded away at the end of the 16th century. In North Frisia, regional sentiments concentrate around the surviving North Frisian dialects, which are spoken by a sizeable minority of the population, though Lower German is far more widespread.

Regional political parties

[edit]| Political party | Active in | Representation | European affiliation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FNP | Frisian National Party Fryske Nasjonale Partij |

EFA | |||

| SSW | South Schleswig Voters' Association Söödslaswiksche Wäälerferbånd |

EFA | |||

Languages

[edit]A half-million Frisians in the province of Friesland in the Netherlands speak West Frisian. Several thousand people in Nordfriesland and Heligoland in Germany speak a collection of North Frisian dialects. A small number of Saterland Frisian language speakers live in four villages in Lower Saxony, in the Saterland region of Cloppenburg county, just beyond the boundaries of traditional East Frisia. Many Frisians speak Low Saxon dialects which have a Frisian substratum known as Friso-Saxon, especially in East Frisia, where the local dialects are called Oostfräisk ("East Frisian") or Oostfräisk Plat (East Frisian Low Saxon). In the provinces of Friesland and Groningen, and in North Frisia, there are also areas where Friso-Saxon dialects are predominantly spoken, such as Gronings. In West Frisia, there are West Frisian-influenced dialects of Dutch such as West Frisian Dutch and Stadsfries.

Maps

[edit]-

Location of Frisia (dark orange) in Europe

-

Historical settlement areas of the Frisians, and areas where a Frisian language is spoken

-

The Frisian territories in Lower Saxony (East Frisia)

-

Frisian colonisation (yellow) of southwestern Jutland during the Viking Age

-

Difference between the historical region and present-day district of Nordfriesland

Flag

[edit]

While the subdivisions of Frisia have their own regional flags, Frisia as a whole has not historically had a flag of its own. In September 2006, a flag for a united Frisia – known as the "Interfrisian Flag" – was designed by the Groep fan Auwerk. This separatist group supports the unification of Frisia as an independent country. The design was inspired by the Nordic Cross flag. The four pompeblêden (water lily leaves) represent the contemporary variety of the Frisian regions – North, South, West and East.[8]

The design was not accepted by the Interfrisian Council.[9] Instead, the council adopted the idea of an Interfrisian flag and created a design of its own, containing elements of the flags of the council's three sections. Neither of the two flags is widely used.

See also

[edit]- Frisian Islands

- Frisian languages

- Frisian cuisine

- List of rulers of Frisia

- Eala Frya Fresena

- Stateless nation

- German Bight

- Wadden Sea

- Zuider Ee

Notes

[edit]- ^

- Dutch, German: Friesland

- Dutch Low Saxon: Fraislaand

- East Frisian Low Saxon: Fräisland

- North Frisian (Amrum, Föhr): Fresklun

- North Frisian (Bökingharde): Fraschlönj

- North Frisian (Goesharde): Freeschlon

- North Frisian (Halligen): Freesklöön

- North Frisian (Heligoland): Friislon

- North Frisian (Karrharde): Fräischlön

- North Frisian (Sylt): Friislön

- North Frisian (Wiedingharde): Freesklön

- Saterland Frisian: Fräislound [ˈfrɛi̯slɔu̯nd]

- West Frisian: Fryslân

- ^ A more extensive, though outdated review of Frisia in Roman times is Springer, Lawrence A. (Jan 1953). "Rome's Contact with the Frisians". The Classical Journal. 48 (4). Northfield, MN: The Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 109–111. ISSN 0009-8353. JSTOR 3292503.

- ^ Ashdown, Margaret, ed. (1930). English and Norse documents : relating to the reign of Ethelred the Unready. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 138. OCLC 458533078. Noted by Homans.[6]: 189

- ^ Homans describes Frisian social institutions, based on the summary by Siebs, Benno E. (1933). Grundlagen und Aufbau der altfriesischen Verfassung. Untersuchungen zur deutschen Staats- und Rechtsgeschichte (in German). Vol. 144. Breslau: Marcus. OCLC 604057407. Siebs' synthesis was extrapolated from survivals detected in later medieval documents.[6]

- ^ This is part of the evidence for a duodenary system, counting by multiples of twelve.[6] : 204 and passim

References

[edit]- ^ cf. Fort, Marron Curtis (1980): Saterfriesisches Wörterbuch. Hamburg, p.45.

- ^ Bos, Jurjen M. (2001). "Archaeological evidence pertaining to the Frisians in the Netherlands". In Munske, Horst H.; Århammar, Nils R. (eds.). Handbuch des Friesischen = Handbook of Frisian studies. Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 487–492. ISBN 9783484730489. Retrieved 2009-01-11.: 480

- ^ Tacitus. Annales IV (in Latin).

- ^ "Frisian language". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-11-13.

- ^ Procopius (1914). The Wars. 8.20.11-46

- ^ a b c d e f Homans, George C. (1957). "The Frisians in East Anglia". The Economic History Review. New series. 10 (2). Wiley: 189–206. doi:10.2307/2590857. ISSN 0013-0117. JSTOR 2590857.

- ^ Baten, Joerg; Steckel, Richard H. (2019). "The History of Violence in Europe: Evidence from Cranial and Postcranial Bone Traumata". The Backbone of Europe: Health, Diet, Work and Violence over Two Millennia: 300–324.

- ^ "Interfrisian flag". Groep fan Auwerk. September 2006.

- ^ Press release from the Interfrisian Council

- Bibliography

- Thomas Steensen: 'Die Friesen. Menschen am Meer', Wachholtz Verlag, Kiel/Hamburg 2020, ((ISBN 978-3-529-05047-3)).

- Albert Bantelmann, Rolf Kuschert, Albert Panten, Thomas Steensen: Geschichte Nordfrieslands. 2., durchges. u. aktualisierte Aufl., Westholst. Verlagsanstalt Boyens, Heide in Holstein 1996 (= Nordfriisk Instituut, Nr. 136), ISBN 3-8042-0759-6.

- Thomas Steensen: Geschichte Nordfrieslands von 1918 bis in die Gegenwart. Neuausg., Nordfriisk Instituut, Bräist/Bredstedt 2006 (= Geschichte Nordfrieslands, Teil 5; Nordfriisk Instituut, Nr. 190), ISBN 3-88007-336-8.

- Stefan Kröger - Das Ostfriesland-Lexikon. Ein unterhaltsames Nachschlagewerk, Isensee Verlag, Oldenburg 2006

- Ostfriesland im Schutze des Deiches. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte des ostfriesischen Küstenlandes, hrsg. im Auftrag der Niederemsischen Deichacht, 12 Bände, Selbstverlag, Pewsum u. a. 1969

- Onno Klopp -, Geschichte Ostfrieslands, 3 Bde., Hannover 1854–1858

- Hajo van Lengen - Ostfriesland, Kultur und Landschaft, Ruhrspiegel-Verlag, Essen 1978

- Hajo van Lengen (Hrsg.) - Die Friesische Freiheit des Mittelalters – Leben und Legende, Verlag Ostfriesische Landschaft 2003, ISBN 3-932206-30-4

- Franz Kurowski - Das Volk am Meer – Die dramatische Geschichte der Friesen, Türmer-Verlag 1984, ISBN 3-87829-082-9

- Karl Cramer - Die Geschichte Ostfrieslands. Ein Überblick, Isensee - Oldenburg

- Hermann Homann - Ostfriesland – Inseln, Watt und Küstenland, F. Coppenrath Verlag, Münster

- Manfred Scheuch - Historischer Atlas Deutschland, ISBN 3-8289-0358-4

- Karl-Ernst Behre / Hajo van Lengen - Ostfriesland. Geschichte und Gestalt einer Kulturlandschaft, Aurich 1995, ISBN 3-925365-85-0

- Tielke, Martin (ed.) - Biographisches Lexikon für Ostfriesland, Ostfries. Landschaftliche Verlag- u. Vertriebsges. Aurich, vol. 1 ISBN 3-925365-75-3 (1993), vol. 2 ISBN 3-932206-00-2 (1997), vol. 3 ISBN 3-932206-22-3 (2001)

External links

[edit]- Profile at Eurominority.eu

- Official website of the Interfrisian Council

- Website of the Groep fan Auwerk