Mansouri Great Mosque

| Grand Mansouri Mosque | |

|---|---|

Arabic: المسجد المنصوري الكبير | |

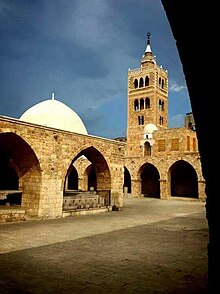

Courtyard, ablution fountain, and minaret of the Grand Mansouri Mosque | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | |

| Governing body | Islamic Awqaf Directorate of Tripoli |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | Tripoli, Northern Governorate |

| Country | Lebanon |

Location of the mosque in Lebanon | |

| Geographic coordinates | 34°26′4.2″N 35°50′33.0″E / 34.434500°N 35.842500°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) |

|

| Type | Mosque architecture |

| Style | Norman and Mamluk |

| Completed |

|

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | One |

| Minaret(s) | One |

| Inscriptions | 4 |

The Mansouri Great Mosque (also known as the Grand Mansouri Mosque, Great Mosque of Tripoli; Arabic: المسجد المنصوري الكبير) is a mosque in Tripoli, Lebanon.[1] It was built in the Mamluk period, from 1294 to 1298.[2] This was the first building to be erected in Mamluk Tripoli.[3] The Grand Mansouri Mosque was built on the ruins of an earlier Crusader church. The current minaret tower was probably part of the Church of St. Mary, possibly with Lombard elements. The mosque's main entrance also appears to incorporate a former Crusader church gate. The rest of the mosque, however, is a Muslim creation dating from after the Mamluk conquest of the city.[4] The Grand Mansouri Mosque is one of the most important historical landmarks of Mamluk-era Tripoli.[3]

History

[edit]The mosque was built on the site of a former Crusader suburb near the Castle of Saint-Gilles (Tripoli Citadel), and has been mistaken for a repurposed Christian church by medieval travelers like al-Nabulsi,[5] and modern historians.[6] The main entrance and the minaret tower are the only remnants of a previous Crusader church, known from contemporary sources as the church of Marie de la Tour (Mary of the Tower). The church fell in disrepair following the massive earthquakes in 1170 and 1201; and as a result of the Mamluk sultan al-Manṣur Qalawun's siege of the city.[7] Although the main entrance and minaret tower originated from a previous Christian structure, the mosque’s core elements—including its courtyard, arcades, fountain, and prayer hall are distinctly Islamic.[6][8]

Known as the Jami al-Mansuri al-Kabir (Great Mansouri Mosque), the mosque was named after al-Manṣur Qalawun, who conquered Tripoli from the Crusaders in 1289.[9] Inscriptions in the mosque reveal that Qalawun's sons, Sultans al-Ashraf Khalil and al-Nasir Muhammad, were responsible for its construction in 1294 and the addition of the courtyard arcades in 1314, respectively.[10][3][11] Six madrasas were built around the mosque during the Mamluk period: al-Khayriyya Hasan Madrasa (c. 1309 or after),[12] al-Qartawiyya (founded c. 1326),[13] al-Nuriyya (14th century),[14] al-Shamsiyya (1349),[3] al-Nasiriyya (1354–1360)[15] and an unidentified "Mashhad" Madrasa.[16][17][18] The mosque played a social, political, and cultural role primarily during the colonial period, when the mosque served as the site for non-violent resistance movements against the French Mandate authorities.[19]

Location

[edit]The Great Mosque is situated in Tripoli's historical center, in an-Nuri neighborhood, on the left bank of the Kadisha River, at the foot and west of the Tripoli Citadel.[3][20][21]

Architecture

[edit]The Great Mosque covers an area of approximately 50 by 60 m (160 by 200 ft).[22] While its facade is relatively simple, the mosque is easily recognized by its prominent minaret and main northern gate, which are the only remains of the Christian church that existed on the site.[3][4] Some scholars hold that the preexisting church was converted into a mosque with only minor Mamluk modifications, rather than being largely new construction; these views, however, are not widely accepted and are primarily based on outdated 19th-century Orientalist scholarship.[23][24]

Crusader craftsmanship is especially visible in the main entrance's design and ornamentation: This rectangular door is framed by a series of arches featuring alternating plain and zigzag stone moldings, which rest on two slender white marble colonnettes and four narrow wall segments. The entrance is preceded by a cross-vaulted passageway. The zigzag motif, known as "chevron" or "dogtooth," has a clear Norman origin and was introduced to the Levant by the Crusaders.[21][3] A closer examination reveals distinctive elements that clarify the doorway’s origins. Behind the main entrance, a row of spiky quatrefoil rosettes decorates the inner side of the arched entryway. These rosettes are not found in Muslim decorative tradition, making it unlikely that a Muslim architect would create them for an Islamic arch. In contrast, identical rosettes appear in Western architecture from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, particularly in Crusader structures in Syria and Palestine. Similar four-petaled rosettes can be seen in Norman architecture throughout Europe, including some Norman buildings in the Levant.[3][25]

The layout of the Great Mosque follows a traditional Islamic arrangement, featuring a central courtyard bordered by single porticoes on the north, east, and west sides, the porticoes consist of identical low arches, complemented by a continuous corridor with simple cross-vaulting behind. The courtyard's qibla side is bordered by a double-vaulted portico leading to the mosque's prayer hall.[11][3] In line with tradition, the mosque has three axial entrances aligned to the north, east, and west, supplemented by two additional entrances flanking the prayer hall. English architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell posits that the three axial entrances are characteristic of Syrian architecture, originating by chance in the Umayyad mosque in Damascus.[3] Upon entering the courtyard, visitors will notice two granite columns rising from the pavement to the right of the main entrance. These remnants from classical times appear to serve no practical or decorative purpose, similar to the two columns in front of Taynal's mosque and the Madrasa Saqraqiyya. The riwaqs were constructed by al-Malik al-Nasir in 1314 when he completed the mosque. At the center of the courtyard, the three-tiered wudu fountain consists of two adjoining square units, one of which is topped with a dome. Al-Nabulsi, who visited Tripoli in 1700, described the fountain as "having a huge dome and pillars so large that four men would be needed to embrace them."[26][27]

The prayer hall measures 51.5 m (169 feet) by 11.3 m (37 feet) and occupies the entire qibla side of the mosque.[28] It is divided into two aisles by six large piers, creating fourteen areas—thirteen covered by simple cross-vaults and the area in front of the mihrab topped by a small dome. The qibla wall features three mihrabs: a main axial mihrab with a rosette above it, accompanied by two side mihrabs and a minbar. The minbar is wooden, adorned with intricate geometric carvings. Above it, a painted rosette—reused from an earlier context—displays the word Allah in its center, with decorative motifs similar to those found at the main entrance. The rosettes in relief surround the circumference of the roundel, with a zigzag pattern forming circles within. This decorative rosette, akin to the style seen at the entrance, likely originated from the same Crusader church.[29][30]

The minaret

[edit]

The square-towered minaret, consisting of four levels, has undergone numerous restorations. Over the last level, an octagonal topped by a conical dome, was added in later times. The minaret's first floor is windowless, the second floor features two arched windows with a central column on each of its four sides. The third and fourth floors have three arched windows on the north and south sides, and two on the east and west ones.[31] The minaret likely belonged to the Crusader Church of St. Mary, which is known to have stood near the base of the Citadel. Although Arab historical records do not detail its distinctive characteristics, Western scholars have debated its unusual form since the 19th century. French diplomat and historian Marquis Melchior de Vogüé,[32] and Swiss historian Max van Berchem diplomat and historian,[33] noted the resemblance between the tower and Christian bell towers of Lombardy in Italy.[4]

Inscriptions

[edit]The building features four inscriptions, two of which document the construction date and the names of its founders. The first inscription, located above the main entrance lintel, measures 260 cm (100 in) by 39 cm (15 in), and is composed of three lines written in naskh script.[3] It reads:

In the name of God the Merciful, the Compassionate, our master the most powerful sultan, lord of Arab and Persian kings, conqueror of the frontiers and exterminator of the infidels, al Malik al Ashraf Salah al Dunya wa l-Din Khalil, the associate of the commander of the faithful, son of our master al Sultan al Malik al Mansur Sayf al Dunya wa l-Din Qala'un al Salihi, may God perpetuate his reign, has ordered the construction of this sacred mosque [jami ], during the governorship of His High Excellency the great Amir al Izzi Izz al Din Aybak al-Khazandar [the treasurer] al Ashrafi al Mansuri, governor of the sultanate in the conquered lands and protected shores, may God forgive him. In the year six hundred and ninety-three.[a] Glory to God the One and Only.[3]

In the left corner between the main entrance lintel and the arch, three short additional lines are tightly inscribed.[3] They mention the name of the mosque architect and read:[34]

The humble servant of God, Salim al Sahyuni, son of Nasir al Din the Persian, oversaw [or undertook] the construction of this blessed mosque. May God forgive him.[3]

The second inscription is located on the eastern wall of the arcade surrounding the mosque's courtyard and marks the mosque's completion. It is inscribed on a white marble plaque, featuring ten lines of naskh script.[3] The inscription reads:

In the name of God, the Merciful and Compassionate, only those who believe in God and the Last Day shall maintain the places of worship of God [Qur'an 9:18]. Our master, the sultan, the king, the victorious, the just, the learned, the warrior, the triumphant, Nasir al Dunya wa l-Din Muhammad ibn Qala'un—may God sustain his reign—ordered these arcades to complete the blessed mosque, during the governorship of His Excellency Kustay al Nasiri, governor of Tripoli, may God grant him victory, under the supervision of Badr al Din Muhammad, son of Abu Bakr, inspector of flourishing diwans, may God lengthen his favor. The construction was completed in the months of the year 715 A.H.[b] May God bless our lord Muhammad. The humble servant of God, Ahmad ibn Hasan al-Ba'abaki, the architect, oversaw its construction.

A third inscription, found on a secondary mihrab to the left of the main mihrab, contains four lines of naskh. It records that in 1478,[3] Usindamur ordered the marble revetment of the mihrab:

The humble servant of God, Usindamur al-Ashrafi, governor of the royal province of Tripoli, the well-protected, ordered the marble revetment of this blessed mihrab. May God grant him victory. This was done under the administration of the judge of judges, the Shafi'ite Imam, in the beginning of Rabi' II in the year 883 A.H.[c] under the supervision of Inspector Muhammad.[3]

The fourth inscription is located on the mosque's minbar, featuring two lines in naskh script. It identifies the donor as Amir Qaratay, the twice-governor of Tripoli, from 1316 to 1326 and from 1332 to 1333, and dates the minbar’s construction to 1326.[3] The inscription reads:

The humble servant of God, Qaratay, son of Abdallah al-Nasiri, ordered the construction of this blessed minbar. May God reward him. The work was entrusted to Bakthuwan, son of Abdallah al-Shahabi, may God accept his efforts, in the month of Dhu al-Qadah, in the year 726 A.H.[d][3]

Relics

[edit]

A hair from the beard of the Prophet Muhammad is stored in the Mansouri Great Mosque. This relic was a gift from Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II to the people of Tripoli in 1891 AD. The gift was presented in recognition of the loyalty of the Tripoli residents to the Ottoman Empire and was sent after the restoration of the Hamidy Mosque. Originally intended for this mosque, the relic was instead placed in the Mansouri Great Mosque, which was larger and more central to the city. The relic is preserved in a golden box and kept in a specially built room within the Mansouri Great Mosque, referred to as the "Room of the Noble Relic." This room has been renovated and transformed into a small religious museum. The relic, is considered one of the most valuable Islamic religious items in Lebanon and is traditionally visited on the last Friday of Ramadan and on the Prophet's birthday. The room also displays other Islamic historical objects, adding to its significance as a cultural and religious site in Tripoli.[35]

Tripoli landmark map

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Petersen 2002, pp. 175, 286.

- ^ Saliba, Jeblawi & Ajami 1995.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Archnet 2024a.

- ^ a b c Salam-Liebich 1983, pp. 23–25.

- ^ Al-Nabulsi 1971, p. 72.

- ^ a b Salam-Liebich 1983, p. 18.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Tadmuri 1994, p. 19-26.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 57.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, pp. 16–18.

- ^ a b Petersen 2002, p. 175.

- ^ Archnet 2024c.

- ^ Archnet 2024e.

- ^ Archnet 2024d.

- ^ Archnet 2024b.

- ^ Archnet 2024f.

- ^ Mahamid 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, pp. 102–132.

- ^ Hamze 2020.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, p. 16.

- ^ a b Tadmuri 1974, p. 58.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, p. 23.

- ^ Sobernheim 1894, p. 51.

- ^ Qattar 1998, pp. 483–484.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, p. 25.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 64.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 69.

- ^ Salam-Liebich 1983, p. 27.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 70.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 59.

- ^ Vogüé 1860, p. 375.

- ^ Berchem 1895, p. 491.

- ^ Tadmuri 1974, p. 62.

- ^ Baalbaky 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Archnet (2024a). "Jami' al-Mansuri al-Kabir". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Archnet (2024b). "Madrasa al-Nasiriyya". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Archnet (2024c). "Madrasa Khayriyya Hasan". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Archnet (2024d). "Madrasa al-Nuriyya". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Archnet (2024e). "Madrasa al-Qartawiyya". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Archnet (2024f). "Anonymous Mashhad". Archnet. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Al-Nabulsi, Abd Al-Ghani (1971) [17th century]. Busse, Heribert (ed.). 'Abd Al-Gani Al-Nabulsi, al-Tuhfa al-nābulusiyya fī l-rihla altarabulusiyya. Beiruter Texte und Studien (in German). Vol. 4. Beirut: Orient-Institut der deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellshaft; F. Steiner. ISSN 1570-0585. OCLC 489759445.

- Baalbaky, Atef (15 April 2023). "تدمري ل nextlb : الأثر النبويّ الشّريف في الجامع المنصوريّ من أثمن الموجودات الإسلامية في لبنان" [Tadmouri to Nextlb: "The Noble Prophetic relic in the Mansouri Great Mosque is one of the most precious Islamic artifacts in Lebanon."]. Next LB (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 13 October 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- Berchem, Max van (1895). "Recherches archéologiques en Syrie". Journal Asiatique (in French). Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hamze, Mounzer (24 September 2020). "Al Mansouri Great Mosqie". mounzerhamze. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

- Mahamid, Hatim (2009). "Mosques as Higher Educational Institutions in Mamluk Syria". Journal of Islamic Studies. 20 (2): 188–212. ISSN 0955-2340. JSTOR 26200738.

- Petersen, Andrew (2002). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-61365-6.

- Qattar, Elias (1998). نيابة طرابلس في عهد المماليك، 688 - 922 هـ / 1289 - 1516م [The Province of Tripoli during the Mamluk Era]. منشورات الجامعة اللبنانية 43 (in Arabic). Beirut: Lebanese University Press. OCLC 587781545.

- Saliba, R.; Jeblawi, S.; Ajami, G. (1995). Tripoli the Old City: Monument Survey - Mosques and Madrasas; A Sourcebook of Maps and Architectural Drawings. Beirut: American University of Beirut.

- Salam-Liebich, Hayat (1983). The Architecture of the Mamluk City of Tripoli. Aga Kahn Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 9780922673094.

- Sobernheim, Moritz (1894). "2e ptie: Syrie du Nord". In Berchem, Max von (ed.). Matériaux pour un Corpus inscriptionum Arabicarum [Materials for a Corpus of Arabic Inscriptions] (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. ISBN 9782724700121. OCLC 13837219.

- Tadmuri, Omar Abdel-Salam (1974). تاريخ وآثار مساجد ومدارس طرابلس في عصر المماليك : من الفتح المنصوري حتى الآن ٦٨٨-١٣٩٤ه ١٢٨٩-١٩٧٤م ؛ دراسة تاريخية لمساجد ومدارس طرابلس التي سادها المماليك، تأسيسها، تسميتها وصفها، هندستها، نقوشها، بناتها، علماؤها / Tārīkh wa-āthār masājid wa-madāris Ṭarābulus fī ʻaṣr al-Mamālīk : min al-fatḥ al-Manṣūrī ḥattá al-ān, 688-1394 H. 1289-1974 M. ; dirāsah tārīkhīyah li-masājid wa-madāris Ṭarābulus allatī shādahā al-Mamālīk, taʼsīsuhā, tasmītuhā, waṣfuhā, handasatuhā, nuqūshuhā, binātuhā, ʻulamāʼuhā [History and Heritage of Tripoli's Mosques and Schools in the Mamluk Era: From the Mansouri Conquest to the Present (688–1394 AH / 1289–1974 CE)] (in Arabic). Dār al-Bilād.

- Tadmuri, Umar Abd es-Salam (1994). آثار طرابلس الإسلامية دراسات في التاريخ والعمارة [Islamic Heritage of Tripoli: Studies in History and Architecture] (in Arabic). دار الايمان للطبع والنشر والتوزيع.

- Vogüé, Melchior (marquis de) (1860). Les églises de la Terre Sainte. Paris: Librairie de Victor Didron.

Further reading

[edit]- Doughty, Dick (2000). "Tripoli - Lebanon's Mamluk Monument". ARAMCO World. Archived from the original on 17 April 2024. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- Meinecke, Michael (1992a). Die mamlukische Architektur in Ägypten und Syrien (648/1250 bis 923/1517): Genese, Entwicklung und Auswirkungen der mamlukischen Architektur [Mamluk architecture in Egypt and Syria (648/1250 to 923/1517): Genesis, development and impact of Mamluk architecture] (in German). Verlag J.J. Augustin. ISBN 978-3-87030-071-5.

- Meinecke, Michael (1992b). Die mamlukische Architektur in Ägypten und Syrien (648/1250 bis 923/1517): Chronologische Liste der mamlukischen Baumassnahmen [Mamluk architecture in Egypt and Syria (648/1250 to 923/1517): Chronological list of Mamluk building projects] (in German). Verlag J.J. Augustin. ISBN 978-3-87030-076-0.

External links

[edit]- Mosque page at the Tripoli tourist site Archived 2019-01-24 at the Wayback Machine, based on NINA JIDEJIAN, Tripoli Through the Ages, Dar El-Mashreq Publishers, Beirut

- 3D virtual tour inside the Mosque